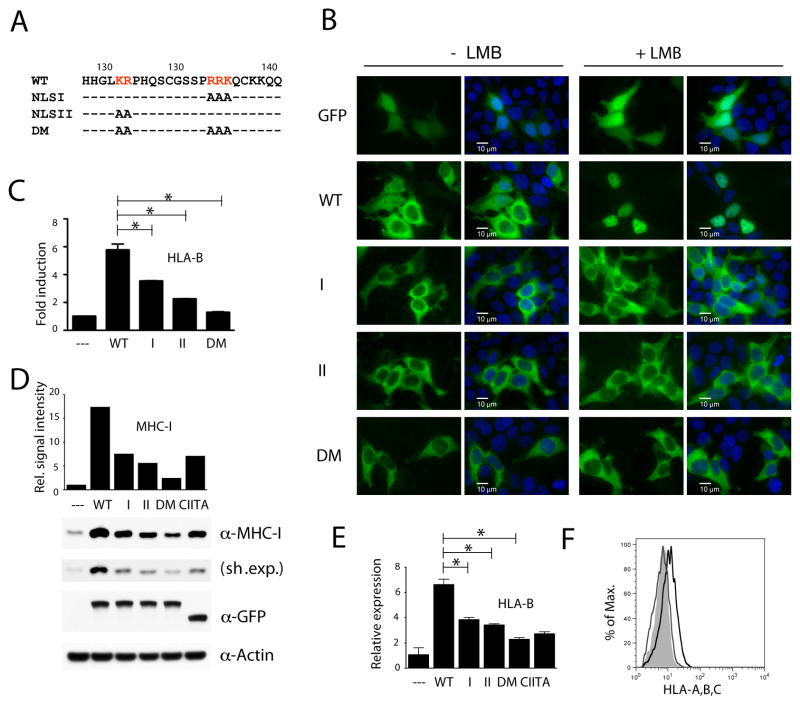

Fig. 1.

NLRC5 requires an intact nuclear localization signal for efficient MHC class I induction.

(A) Sequence of the NLRC5 bipartite NLS in the N-terminus and the indicated mutant versions used in this study. Alanine substitution of the right or left arm of the NLS was used to construct the NLSI and NLSII import mutant expression plasmids. DM: double mutant. (B–F) HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with either expression vectors for GFP, GFP-NLRC5, or GFP-CIITA. (B) Subcellular localization of wild-type and NLS mutant NLRC5 upon LMB treatment (100 nM, for 2 hrs). Scale bar: 10 μm. (C) Reporter gene analysis of the HLA-B promoter. An HLA-B luciferase reporter construct was co-transfected with the indicated plasmids and cell lysates were analyzed 48 hrs post transfection by dual-luciferase assay. Data are a representative of several independent experiments performed in duplicates and are plotted as fold induction with respect to the GFP control vector (--). Error bars represent ± SD. *p < 0.05. (D) Cell extracts were examined for the expression of MHC class I heavy chain by immunoblotting 48 hrs post transfection. Sh. Exp., short exposure. MHC class I signal intensities, obtained by densitometric analysis, were normalized by β-Actin levels (bar diagram). The GFP blot demonstrates equal expression of the NLRC5 and CIITA fusion proteins. (E) RNA samples were isolated and HLA-B transcripts were quantified by qRT-PCR using gene specific primers. (F) Quantitative analysis by flow cytometry using an anti-MHC class I antibody. WT (black line), DM (grey line), empty vector control (shaded histogram).