Abstract

Exhaustive enumeration of sequences and folds is conducted for a simple lattice model of conformations, sequences, and energies. Examination of all foldable sequences and their nearest connected neighbors (sequences that differ by no more than a point mutation) illustrates the following: (i) There exist unusually large number of sequences that fold into a few structures (super-folds). The same observation was made experimentally and computationally using stochastic sampling and exhaustive enumeration of related models. (ii) There exists only a few large networks of connected sequences that are not restricted to one fold. These networks cover a significant fraction of fold spaces (super-networks). (iii) There exist barriers in sequence space that prevent foldable sequences of the same structure to ‘connect’ through a series of single point mutations (super-barrier), even in the presence of the sequence connection between folds. While there is ample experimental evidence for the existence of super-folds, evidence for a super-network is just starting to emerge. The prediction of a sequence barrier is an intriguing characteristic of sequence space, suggesting that the overall sequence space may be disconnected. The implications and limitations of these observations for evolution of protein structures are discussed.

Keywords: mutations, lattice models, protein evolution, foldable sequences, contact energies

Introduction

One of the intriguing questions in molecular evolution is the origin and development of protein structures or folds1. Are proteins trapped in a set of limited folds initiated by chance? Does evolution connect different fold families retaining the stability of the evolving protein? This manuscript explores, with exhaustive enumeration, a network of sequence flow between stable caricatures of proteins using a simple exact model (SEM) of polymers on a two dimensional lattice.

Properties of SEM, and their proposed impact on evolution, were investigated extensively in the past (for an excellent review see 2). An important parameter describing the evolution of protein structures is sequence capacity 3,4, also called protein designability 5–8. We define capacity of a structure as the number of sequences that fold into that protein shape. The connection to evolution was made by Sewall Wright who introduced the notion of evolutionary fitness landscape to describe evolutionary processes 9. Sequences that fold into a particular structure are also called the neutral set if the fitness criterion is set to protein stability. Capacity was suggested as relevant to the apparent rate of evolutionary changes of expressed proteins 10–14 and was discussed extensively in the past.

Sequence capacity is one way to measure the presence of the intriguing super-folds, or structures with exceptionally large neutral sets14,15. Super-folds are protein structures with unusually high sequence capacity. Experimental analyses of super folds 16,17 are based on genomic data mining and classification of protein sequences into fold families. It is shown that genomic sequences populate disproportionally a few fold families that were called super-folds. These empirical studies motivate theoretical and computational research of the origin of this asymmetry. One explanation is based on the stability of a single chain 10,14,18,19. In brief, stability analysis of a single isolated chain is argued to explain these anomalies. Higher capacity is associated with larger protein stability since more stable structures can accommodate a larger number of mutations, some of them ‘harmful’.

Entropy in sequence space is a more direct measure of the capacity and is computed directly with stochastic approaches 4,5,12,20,21 or modeled theoretically 20. A number of computer simulations of protein models on simple lattices illustrate the existence of super-folds. Simulations employ exact enumeration (e.g. 6,8,22–24) or stochastic algorithms (Metropolis Monte Carlo21,25) to generate self-avoiding walks on the lattice and alternative sequences, and were successful in demonstrating the feasibility of superfolds, consistent with the basic hypothesis.

Subsequent studies computing the capacities of actual protein folds for a large selection of protein structures support the simpler calculations 4,26. Another and more recent experimental observation on sequence/fold space is of proteins that switch folds27, or the so called network of sequence flow26,28. We define a switch of a fold (or a ‘flip’) as a dramatic change in the basic structure of a protein following a single point mutation. A beautiful experimental example of a flip is from a helical bundle to an alpha helix/beta sheet sandwich 29. The two structures, before and after the mutation, are thermally stable. The experiment was done in parallel to computational exploration of the network of sequence flow. The calculations26,28 use representative experimental structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB [18]) and estimate probabilities of flipping between folds with Markov chains in sequence space. The calculations show a network of switching between folds connecting essentially all experimental structures. This surprising observation has significant implications to protein evolution and design. It suggests (for example) that the number of folds in the beginning or the ‘big bang’ of fold evolution could have been much smaller than what we see today. The emergence of new folds may have followed subsequent point mutations and divergence to new folds. It also suggests that proteins with one stable conformation could be perturbed to a significantly different fold. A perturbation (not only a point mutation but also environment change) can alter their stable folds and potentially their functions.

Prior to the calculation on actual protein folds chosen to cover the PDB, flips between folds were considered using SEM. Exhaustive enumeration of structures and sequences based on a two-letter code8 (H/P) was conducted on a two dimensional lattice. The conclusions of this study were different from our investigation of the network of sequence flow26,28. In the SEM study8 an argument was put forward that a significant number of point mutations separate two folds and therefore a transition between two unique structures is unlikely. Hence, a network between folds, induced by point mutations, is not significant in practice. The qualitative difference from the network of sequence flow, which claims connectivity for the whole set of structures of the PDB, is quite striking.

A network of point mutations connecting alternative secondary structure of RNA were found computationally and experimentally30. This finding for another important biomolecule supports an expectation for a similar behavior in proteins. The experimental evidence for the existence of structural flips in proteins is weaker than in RNA. However, as discussed in a previous paragraph, it is not zero.

Interestingly, not all sequences that belong to a particular fold are connected. Namely, a sequence S that folds to a structure X is not necessarily connected by a series of point mutations to another sequence S’ that folds to the same structure (Figure 1). We call the separation in sequence space between sequences that belong to the same fold a barrier. Separation of sequence space that belongs to the same fold in SEM were recognized in the past2. The barrier here, however, is more general since it includes the possibility of sequence flow between folds and the set of sequences at hand may correspond to more than one fold.

Figure 1.

Example of sequences that fold to same conformation but do not form a network set. A network set is the collection of sequences that can be connected by a series of point mutations between viable sequences. Note that sequences 1 and 3 are related, 2 and 4 are related.

H + PPPHPP + H − PHH

H + PPPHPP − H + PHH

H − PPPHPP + H − PHH

H − PPPHPP − H + PHH

It is therefore of interest to examine why the conclusions of the SEM studies8 regarding the network of sequence flow are different from those of a Markov chain in sequence space for actual protein folds26,28. If the weights of structural flips are indeed very low then stochastic sampling by a Markov chain should not have sampled these flips, in contrast to our investigations. One reason for the disagreement may be the use of different measures. The SEM studies considered a mutational distance between folds, while the Markov sampling searched stochastically sequences leading to transition between folds. Another reason can be the size of the alphabet. Markov chain sampling was conducted using twenty types of amino acids. It is therefore possible that the limited alphabet influences the rate of flips between structures. The advantage of the two-letter alphabet is that comprehensive evaluation of all point mutations and their impact on the evolution of structures can be made, something we cannot do with 20-letter alphabet. The question we pose in the present manuscript is: Can we use a SEM model that mimics the results of sampling sequences stochastically in three-dimensional protein folds to investigate in greater details the network of sequence flow?

The simple model we start from is of self-avoiding walks on a two-dimensional square lattice, a model that was used extensively by Dill and co-workers6,22. The use of a two dimensional lattice is advantageous to a three-dimensional representation since the number of possible conformations is much smaller. Moreover, hydrophobic cores, a driving force to protein stability, can be realized with much shorter sequences than those required in three dimensions. The disadvantage (of course) is that two-dimensional models miss one dimension found in more realistic representations of proteins. The most broadly used model of proteins that was investigated on these lattices is the HP model22.

The HP model has only two types of amino acids, Hydrophobic (H) and Polar (P). Hydrophobic residues attract each other, while polar residues are neutral when interacting with other amino acids. The HP model was investigated extensively from chemical, physical, and mathematical viewpoints. Despite its simplicity, it is rich, provides significant insight to mechanisms of protein folding, and presents intriguing computational and mathematical challenges. The problem from our perspective with the HP model is that it is highly degenerative and the number of sequences that fold into unique structures is small. We wish to have a reasonably large number of foldable sequences (that can still be enumerated exactly) leading to statistically more meaningful results. Other versions of the HP model such as penalizing exposed hydrophobic residues or changing the energy value of the three contact types (HH, HP and PP) have been used31–33. These proposed modifications to the original HP energy have resulted in models that are less degenerative, but the results are unstable. Simple changes to the model (such as changing one contact value) can result in significantly different global results.

Other more complex models1,31,34–37 have been proposed while trying to keep the model simple enough to be tangible. One example is the HPL model where H=hydrophobic, P=polar, and L=ligand. After numerous exploratory enumerations and analyses we settled on the four types of amino acids (H/P/+/−) introduced in38 (see Tables 1 and 2) as appropriate for our task. In the rest of the paper we describe the model, the enumeration, and our analysis identifying superfolds and supernetworks. The model in38 was introduced to increase ruggedness to the energy landscape, making the folding problem more complex. The H/P model has a smoother energy landscape. The degree of landscape ruggedness for actual protein energy surfaces is open for debate, and we expect both models to have a domain of interest.

Table 1.

A contact potential for model +2

| Contact type | H | P | + | − |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | −1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| P | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| + | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| − | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

Table 2.

A contact potential for model +1

| Contact type | H | P | + | − |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | −1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| P | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| + | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| − | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

The Model

We consider all possible 14-mers made of H,P,+,− ‘amino acids’. The total number of possible sequences is 414 (268,435,456). The linear polymer is embedded in a two-dimensional square lattice (a node represents an amino acid) with bond length of one between sequential monomers separated by a lattice constant. A particular arrangement of a polymer on the lattice is called a conformation. The energy of a conformation is a sum of contact energies between the monomers. A contact is defined between two monomers separated by no more than distance. Tables 1 and 2 determine the value of the contact energies for our two models. No contacts are assumed between sequential monomers along the 14-mers.

We chose not to use the HP model since as mentioned above the original model is highly degenerate, producing a relatively small number of sequences with unique structures. Other versions of the HP model are sensitive to the values of HP, HH, or PP connections, making it difficult to reach meaningful conclusions. For the (H,P,+,−) model, we found that the results are less sensitive to changes in contact energies (scores of +1 and +2 were tried for (+,+) and (−,−)) with most of the same foldable sequences (greater than 60%) and conformations (greater than 80%) being in both models. Furthermore, the four amino acid model provides significantly more sequences to examine, while keeping the problem manageable. The HP model has only a total of 16,384 sequences for the 14-mers, making the number of foldable sequences especially large as a percent of the total number of sequences (models we checked ranged from over 25% of possible sequences folding to over 50% of possible sequences folding, our model has approximately 3.2% of all possible sequences folding).

The generation of conformations on the lattice is not confined to compact states (with maximal number of contacts). From the complete set of self-avoiding walks on the square lattice we only removed symmetry related paths. Self-avoiding paths are removed if they are related to other paths in the set upon rotations or reflection of the whole path. We solve the problem of symmetry-by-rotation by fixing the position of the first two nodes (or the first edge) and grow the rest of the paths in all possible self-avoiding directions. Using the complex plane, reflections are excluded by checking for the negative conjugate of the positions of the original coordinates of a conformation. For example the walk {0, i, 1 + i, 1 + 2i} has a reflection {0, i, −1 + i, −1 + 2i}. The number of conformations left is 110,188. To explore reasonable variation in parameters we considered two choices of repulsion for (−,−) and (+,+) interactions: values of +1 and +2. We call the two options the ‘+1 model’ and the ‘+2 model’.

The results obtained by the different models vary only in the number of viable sequences and number of “active” conformations (conformations that have at least one sequence fold to it). The +1 model gives more sequences that are foldable than the +2 model, and more ‘active’ conformations. Again, we state that over 80% of the active conformations and over 60% of sequences are the same in both models. We say that a sequence is in conformation set X, if conformation X gives the unique lowest energy of all self-avoiding walks on the lattice for that sequence. If a sequence’s lowest energy is not unique among all self-avoiding walks then the sequence is not foldable. All energies of foldable conformations must have negative energy since the stretched conformation has zero energy (no contacts) regardless of the sequence and we do not accept that conformation as viable. For the +1 model we have 8,804,514 foldable sequences, and for the +2 model 6,275,476 sequences.

The total energy (E) is given by:

where f(α,β) is the contact value from Table 1 (or Table 2) given for the (α,β) types of the amino acids.

Results

In discussing the results of the model we will use the following definitions:

A conformation set X is the set of all sequences that fold to conformation X.

Two sequences are connected if they vary at only one position along the sequence, (i.e. {HHPPP,HHPPH} are connected but {HHPPP,HHHHP} are not connected).

The connections of a sequence are the set of all sequences to which it is connected.

A network set is the set of all sequences in which a series of connected sequences (all in the same set) can be found from any member A of the set to any other member B.

For example, {HHPPP,HHHPP,HHHHP} are in same network set though {HHPPP and HHHHP} are not connected. Conversely {HHPPP,HHHPP,HHHHH} cannot be a network set as there is no series of connected sequences (in the set) leading from either {HHPPP or HHHPP} to {HHHHH}.

Connections

If all sequences were considered, each sequence would have 42 connections (3 changes per node multiplied by 14 nodes). However, only subsets of sequences are foldable and these numbers are therefore expected to drop. For the +2 model we have on average 13.7 connections for any foldable sequences, while for the +1 model the number is slightly larger at 14.2. The maximum number of connections observed for any foldable sequence is 33 (eight sequences from the set of the +2 model) versus 34 (six such sequences of the +1 model). There are 38 sequences with no connections in the +1 model. The distribution of connections is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A histogram plot of the number of sequences found with a different number of connections (point mutations to other foldable sequences).

It is useful to examine these results with a random model for a reference. We consider sets of sequences of the same number of members as in the +2 or +1 sets. These sets of random sequences are sampled uniformly and at random from the complete set of sequences (without the requirement that the sequences will be foldable). We find the average number of connections of 1.014 (reference to +2 model), and 1.5 connections (reference to +1 model). The variances in the number of connections were approximately 1 and 1.5 respectively. The maximum numbers of connections for the random models were 9 and 13 for the +2/+1 cases. Hence, foldable sequences are significantly more connected compared to random sets (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Histogram of percent of the number of sequences sampled at random (blue) or from model +2 (red) as a function of the number of connections each sequence has on the average. A connection is defined between a pair of sequences if a single change in the identity of a monomer transform the sequence to another foldable sequence but in another conformation.

Networks

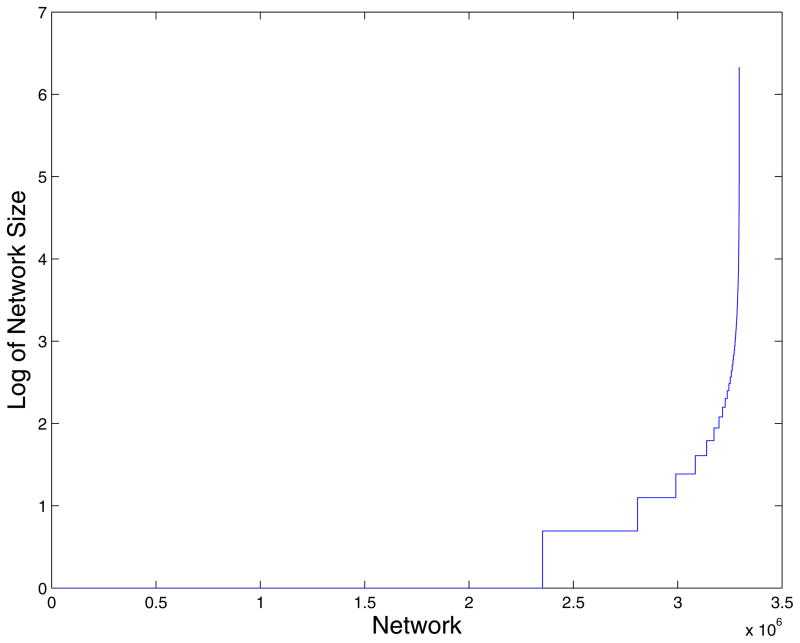

For the +1 model there are 188 Network Sets. From the random version of this model we get approximately 2.94 million networks sets. The largest network set from foldable sequences in the +1 model has a total of 8,803,506 sequences in it. This one network accounts for more than 99.98% of the viable sequences. The remaining 1008 foldable sequences are spread through the remaining 187 network sets. The largest network size from the random samples has approximately 4.27 million sequences in it (less than 50% of all random sequences). For the +2 model there are 284 Network sets. The largest network consists of 6,271,805 of the possible sequences (99.94% of the foldable sequence set) with the remaining 3671 sequences in the remaining 283 networks. The distributions of network sizes for the +2 model and for the random model are shown in Figures 4 and 5. From the random version of this model we get approximately 3.29 million networks. The appearance of these networks suggests that the small mutation (one amino acid change) from one generation to the next is insufficient to cover sequence and conformation spaces. If a more general mechanism of mutations is considered (in addition to one point mutation at a time, we also consider mutations of two nearby residues in a single step at a time), then the number of network is reduced significantly, but the networks remained disconnected. For example, in model +2 the number of network is reduced from 284 to 7. If the number of sequential amino acids that are allowed to change in one step is increased to 3, only one network remains. These changes mimic a proposed process of domain swaps in evolution of protein structures39.

Figure 4.

A log-log plot of the distribution of network sizes for the +2 model. The networks are sorted by their sizes and plotted sequentially. Note the single dominant network at the right.

Figure 5.

The same as in Figure 4 but this time for the random model. The random model has the same number of sequences as the number of viable (foldable) sequences of the +2 models that are sampled uniformly from the complete set of the sequences. Note tha the umber of networks is in the millions.

Conformations

Consider the sequences of a conformation set. Sequences of the conformation set may connect to sequences in other conformations to create a network set (connecting not only sequences but also conformations). It is of interest to examine the ratio of connections of a sequence that are inside and outside the conformation set of the sequence. In both models (+2/+1) the probability that a sequence is in the same conformation set is relatively high. For the +1 model we have 75.61% of the connections of the sequences in the same conformation set. 620,859 sequences are connected only within the conformation set. In Figure 6 we show the number of sequence with a fraction of connections to the same conformation set.

Figure 6.

The number of sequences as a function of the fraction of sequence connection to the same conformation set.

There are also 512 sequences that have no connections in the same conformation set. Interestingly 474 of these sequences are in the largest network (which we call a supernetwork) with an average number of connections of 14.5. The remaining 38 sequences are in other networks with an average of 11.89 connections (below the average for the whole set). For the +2 model we have a similar fraction (76.74%) of connections on average being in the same set. This time there are 654,904 sequences that are fully connected within the conformation set. 207 sequences have no connection to the same conformation set with 199 of these in the supernetwork. We find 13.85 an average number of connections for these sequences. Only 8 other such sequences are found in other networks with an average number of connections of 10.625 (again below the overall average).

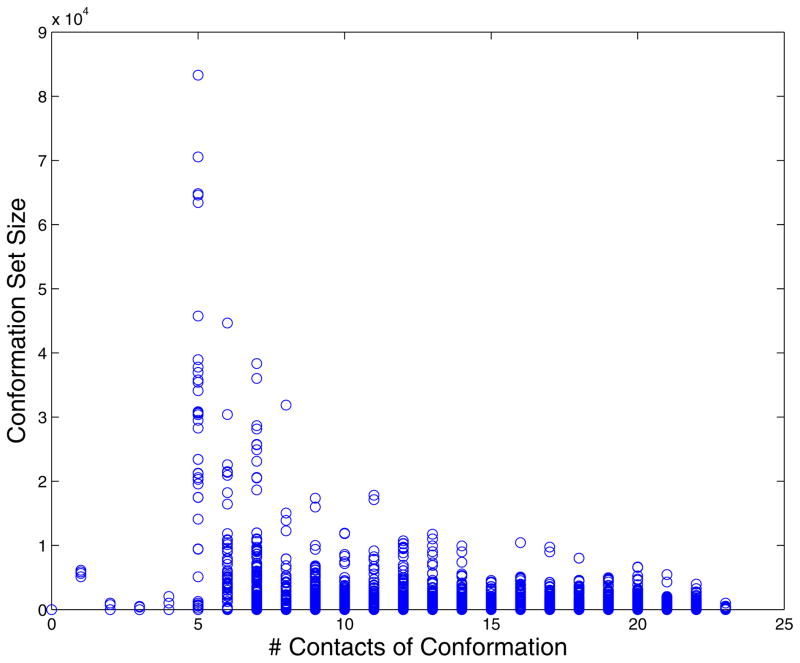

The number of connections for each sequence in our model is high compared to the random model. The last observation and the small number of networks (note networks can span a large number of conformations), suggest that a model of evolution with only a few sequences evolving to fill out sequence space is plausible. The sequence space is well connected and allows for sequence migration between folds. Examining in more detail what conformations are covered by the largest network we have: (1) For the +1 model there are 6,506 conformations populated by foldable sequences. The supernetwork covers all conformations except fifteen. The sequences of the remaining 15 conformations are isolated from other conformations and connected only to sequences in the same conformation. (2) For the +2 model there are 6811 conformations with foldable sequences. Of these conformations all but 39 are accounted for in the supernetwork. This time 3 of the 39 conformations have connected sequences. The rest of the 36 conformations have sequences that connect only to the same conformation. In Figure 7 we present the logarithm of a conformation set size (the number of sequences that fold to a conformation) versus a conformation index. In Figure 8 we correlated the size of a conformation set and the number of conformations it is connected to.

Figure 7.

Distribution of conformation set sizes: +2 model is blue, +1 model is red.

Figure 8.

The number of sequences that fold into one conformation versus the number of other folds that are connected to this conformation via a single point mutation. (+2 model)

Barrier

We also observed sequences that belong to the same fold but are not connected to each other with the same fold (or even the network set). In Figure 1 we illustrate one such a case for a barrier in the space of viable sequences. In this particular case there is a good mixture of repulsive and attractive residues making the composition more diverse and more difficult to flip the type of the amino acids at the different sites. The barrier is clearly the opposite side of the supernetwork, limiting connectivity between folds and within folds. The presence of the barriers should raise a warning flag for algorithms that sample sequences stochastically using Markov Chains. Barriers of the type we detected cannot be overcome with stochastic sampling and even the use of multiple seeds is not likely to “fish” them out. The reason for this being that at least in the present model they are quite rare. On the other hand the observation that the sequences off the supernetwork are rare also suggests that they are not statistically significant, and could be (if accidently sampled) eliminated during the course of evolution due to structural instabilities induced by mutations. In Figure 9 we show an extreme example of a sequence that is connected to nothing.

Figure 9.

Example of a viable sequence (a sequence that folds into a unique conformation) that is not connected via a single point mutation to other viable sequences.

Conclusions

For an exactly enumerated model we have demonstrated the following: The space of viable sequences (and therefore conformations) deviates significantly from random sample by the number of connections and the existence of supernetworks. We observe the difference most clearly in the significantly higher number of average connections between viable sequences compared to a random model and the dominance of a single supernetwork of sequences and folds. Our model suggests that a plausible evolutionary path can be based on only one or a few sequences. There are relatively few networks of connected sequences in our model with the vast majority of sequences (over 99%) belonging to a single sequence supernetwork. This supernetwork covers all superfolds, and most orphan folds with smaller sequence spaces. The remaining sequences (and conformations) are small and tend to be highly isolated. These results suggest that from an evolutionary standpoint the supernetwork was highly likely from the outset. Since any one initial functional protein was highly likely to be in this network to begin with, it is therefore ready to evolve to the rest of the viable sequences of the supernetwork.

There are some fundamental differences between the results of the present model and that of H/P analyses8,14,19,40. For example, we did not find a core sequence to a fold. Instead we find a large number of alternative sequences with moderately low energy. The average energy of the transition sequence (−3.44) is actually lower than the average energy of sequences that are connected only to the same fold (−2.47). For the +2 model 10.4% of the sequences are assigned to a unique fold. Of the sequences that fold 89.6% in our model are transitional. Hence the transitional sequences are highly significant. The number of transient sequences (connected with one point mutation to more than one fold) is actually larger than the number of sequences connected only to the same fold in the SEM model. Our more rugged energy landscape with a larger alphabet seems to be of sufficient complexity to support the notion of flow of sequence network. At the same time the model remained sufficiently simple to allow for exact enumeration and only moderate deviation from the seminal H/P model.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by NIH grant GM067823 to RE

References

- 1.Goldstein RA. The structure of protein evolution and the evolution of protein structure. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2008;18(2):170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan H, Bronberg-Bauer E. Perspectives on ProteinEvolution From Simple Exact Models. Applied Bioinformatics. 2002;1(3):121–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyerguz L, Kempe D, Kleinberg J, Elber R. The evolutionary capacity of protein structures. RECOMB ACM; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyerguz L, Grasso C, Kleinberg J, Elber R. Computational analysis of sequence selection mechanisms. Structure. 2004;12(4):547–557. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shakhnovich EI. Protein Design: A perspective from simple tractable models. Folding and Design. 1998;3(3):R45–58. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(98)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan HS, Dill KA. Sequence space soup of proteins and copolymers. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1991;95(5):3775–3787. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li H, Helling R, Tang C, Wingreen N. Emergence of preferred structures in a simple model of protein folding. Science. 1996;273(5275):666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bornberg-Bauer E. How are model protein structures distributed in sequence space? Biophys J. 1997;73:2393–2403. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78268-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright S. The roles of mutation, inbreeding, crossbreeding, and selection in evolution. In: Jones D, editor. Proceeding of the Sixth International Congreess on Genetics. I. New York: Brooklyn Botanic Gardens; 1932. pp. 356–366. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeldovich KB, Berezovsky IN, Shakhnovich EI. Physical origins of protein superfamilies. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2006;357(4):1335–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Betancourt MR, Thirumalai D. Protein sequence design by energy landscaping. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2002;106(3):599–609. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saven JG, Wolynes PG. Statistical mechanics of the combinatorial synthesis and analysis of folding macromolecules. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 1997;101(41):8375–8389. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drummond DA, Bloom JD, Adami C, Wilke CO, Arnold FH. Why highly expressed proteins evolve slowly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(40):14338–14343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504070102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bornberg-Bauer E, Chan HS. Modeling evolutionary landscapes: Mutational stability, topology, and superfunnels in sequence space. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(19):10689–10694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Govindarajan S, Goldstein RA. Evolution of model proteins on a foldability landscape. Proteins-Structure Function and Genetics. 1997;29(4):461–466. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(199712)29:4<461::aid-prot6>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huynen MA, van Nimwegen E. The frequency distribution of gene family sizes in complete genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15(5):583–589. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qian J, Luscombe NM, Gerstein M. Protein family and fold occurrence in genomes: Power-law behaviour and evolutionary model. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2001;313(4):673–681. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Govindarajan S, Goldstein RA. Why are some protein structures so common? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(8):3341–3345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wroe R, Bornberg-Bauer E, Chan HS. Comparing folding codes in simple heteropolymer models of protein evolutionary landscape: Robustness of the superfunnel paradigm. Biophysical Journal. 2005;88(1):118–131. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.050369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.England JL, Shakhnovich EI. Structural determinant of protein designability. Physical Review Letters. 2003;90(21) doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.218101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shakhnovich EI. Proteins with selected sequences fold into unique native conformation. Physical Review Letters. 1994;72(24):3907–3910. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lau KF, Dill KA. A lattice statistical-mechanics model of the conformational and sequence-spaces of proteins. Macromolecules. 1989;22(10):3986–3997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dinner A, Sali A, Karplus M, Shakhnovich E. Phase-diagram of a model protein-derived by exhaustive enumeration of the conformations. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1994;101(2):1444–1451. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shakhnovich E, Gutin A. Enumeration of all compact conformations of copolymers with random sequence of links. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1990;93(8):5967–5971. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camacho CJ, Thirumalai D. A criterion that determines fast folding of proteins: A model study. Europhys Lett. 1996;35(8):627–632. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyerguz L, Kleinberg J, Elber R. The network of sequence flow between protein structures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(28):11627–11632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701393104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bryan PN, Orban J. Proteins that switch folds. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2010;20(4):482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao BQ, Elber R. Computational exploration of the network of sequence flow between protein structures. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2010;78(4):985–1003. doi: 10.1002/prot.22622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexander P, He Y, Chen Y, Orban J, Bryan P. The design and characterization of two proteins with 88% sequence identity but different structure and function. 2007. pp. 11963–11968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fontana W, Stadler PF, Bornbergbauer EG, Griesmacher T, Hofacker IL, Tacker M, Tarazona P, Weinberger ED, Schuster P. RNA folding and combinatory landscapes. Phys Rev E. 1993;47(3):2083–2099. doi: 10.1103/physreve.47.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blackburne BP, Hirst JD. Evolution of functional model proteins. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2001;115(4):1935–1942. doi: 10.1063/1.2056545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hart WE. On the computational complexity of sequence design problems. Proceeding of the first Annual Int Conf Comput Mol Biol. 1997;1:128–136. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyazawa S, Jernigan RL. Estimation of effective interresidue contact energies from protein crystal-structures - quasi-chemical approximation. Macromolecules. 1985;18(3):534–552. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams PD, Pollock DD, Goldstein RA. Evolution of functionality in lattice proteins. Journal of Molecular Graphics & Modelling. 2001;19(1):150–156. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(00)00125-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller DW, Dill KA. Ligand binding to proteins: The binding landscape model. Protein Science. 1997;6(10):2166–2179. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khodabakhshi AH, Manuch J, Rafiey A, Gupta A. Inverse Protein Folding in 3D Hexagonal Prism Lattice under HPC Model. Journal of Computational Biology. 2009;16(6):769–802. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2008.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helling R, Li H, Melin R, Miller J, Wingreen N, Zeng C, Tang C. The designability of protein structures. Journal of Molecular Graphics & Modelling. 2001;19(1):157–167. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(00)00137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keasar C, Elber R. Homology as a tool in optimization problems - structure determination of 2d heteropolymers. Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1995;99(29):11550–11556. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, Eisenberg D. 3D domain swapping: As domains continue to swap. Protein Science. 2002;11(6):1285–1299. doi: 10.1110/ps.0201402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cui Y, Wong WH, Bornberg-Bauer E, Chan HS. Recombinatoric exploration of novel folded structures: A heteropolymer-based model of protein evolutionary landscapes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(2):809–814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022240299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]