Abstract

Cytochrome ba3 (ba3) of Thermus thermophilus (T. thermophilus) is a member of the heme-copper oxidase family, which has a binuclear catalytic center comprised of a heme (heme a3) and a copper (CuB). The heme–copper oxidases generally catalyze the four electron reduction of molecular oxygen in a sequence involving several intermediates. We have investigated the reaction of the fully reduced ba3 with O2 using stopped-flow techniques. Transient visible absorption spectra indicated that a fraction of the enzyme decayed to the oxidized state within the dead time (~1 ms) of the stopped-flow instrument, while the remaining amount was in a reduced state that decayed slowly (k = 400 s−1) to the oxidized state without accumulation of detectable intermediates. Furthermore, no accumulation of intermediate species at 1 ms was detected in time resolved resonance Raman measurements of the reaction. These findings suggest that O2 binds rapidly to heme a3 in one fraction of the enzyme and progresses to the oxidized state. In the other fraction of the enzyme, O2 binds transiently to a trap, likely CuB, prior to its migration to heme a3 for the oxidative reaction, highlighting the critical role of CuB in regulating the oxygen reaction kinetics in the oxidase superfamily.

Keywords: Cytochrome oxidase, bioenergetics, Raman scattering, stopped flow

1. Introduction

The heme-copper oxidase family of enzymes catalyzes the four electron reduction of molecular oxygen to water, concomitantly producing a proton gradient across the associated membranes. The chemical intermediates formed during the catalytic turnover have been clarified by studies of a variety of mammalian and bacterial aa3 enzymes, which show a progressive R→A→P→F→O transition (where R, A, P/F and O are the fully-reduced, O2-bound, ferryl and oxidized states of the enzymes, respectively) (Fig. S1 in Supplementary Data). The cytochrome ba from Thermus thermophilus shares the architecture of the catalytic sites with aa3 type of enzymes [1], although in this oxidase CuB is known to have an unusually high affinity towards carbon monoxide (CO), with a Ka of 104 M−1 with respect to 87 M−1 of the bovine aa3 enzyme [2, 3]. Thus, whereas the reaction of the enzyme with CO follows the same pathway as other oxidases as illustrated in Eq. 1, k−2 is about 30-fold larger than that in bovine cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) [2] and consequently the CO-bound Cu species is readily detected under equilibrium conditions[1, 4].

| Eq. 1 |

However, although the CO-binding has been heavily investigated in ba3, it is has not been determined if the CuB affinity for O2 is also unusual, resulting in O2 reduction kinetics that are distinct from that in other heme-copper oxidases.

Despite several studies, the reaction kinetics of the ba3 enzyme with O2 is controversial [2, 3, 5]. With stopped-flow optical absorption, Giuffré et al. observed a single exponential kinetic phase at 20 °C, with a rate constant of 200 s−1, which is significantly slower than that of the aa3 enzymes (700–1000 s−1) [2]. They assigned the phase to the F → O transition, which is usually the rate-limiting in the single turnover reaction of other heme-copper oxidases. In contrast, using the CO photolysis method, Smirnova et al. reported that the reaction rate of the F → O step (1100 s−1 at 22 °C) was comparable to that in the aa3 oxidases, and only a minor component (10–13 %) showed a slower reaction rate (~200 s−1) [5]. Similarly, using CO photolysis combined with electrometric measurements at 23 °C, Siletsky et al. showed that the major kinetic phase of the reaction associated with the F→O transition displayed a rate constant of 1300 s−1, while the minor (~3%) slower component showed a rate constant of 400 s−1[3].

In this study, we sought to clarify the origin of the aforementioned differences, to gain a better understanding of the kinetics of the ba3 reaction, and to examine whether the CuB affinity for O2 plays a key role in the catalytic turn-over of ba3. To this end, we re-examined the absorption changes upon stopped-flow mixing of O2 with the reduced enzyme, and studied the reaction with time resolved resonance Raman spectroscopy.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Materials

Cytochrome ba3 was prepared as described previously [6]. The protein was concentrated to ~100 μM in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, with 1 mM dodecylmaltoside. The samples were stored at 4°C. Bovine CcO was isolated and purified as described [7] and stored at 77 K. The mixed valence F (mvF) preparation was made by mixing the bovine CcO with H2O2 [8] and the mixed valence P (mvP) sample was prepared by exposing the enzyme to a 1:1 mixture of CO and O2 [9] at the room temperature.

2.2 Spectroscopic measurements

Time-resolved UV-visible absorption spectra were measured at 8° C on an Applied Photophysics PiStar system equipped with a stopped flow apparatus, a photodiode array detection system, an anaerobic accessory and a temperature control unit. The time zero (t = 0) point and its uncertainty of the stopped flow system were determined employing a test reaction comprised of 2,6-dichlorophenol-indophenol and ascorbic acid [10]; the uncertainty was determined to be at the limit of the minimum sampling time (1.4 ms) of the system. Thus we are unable to determine precisely the relative amplitude of the missing early phase. The ba3 sample was fully reduced by a slightly excess amount of sodium dithionite, and mixed with an O2 saturated buffer in the stopped flow apparatus at a 1:1 ratio. Alternatively, the enzyme (40 μM) was reduced with ascorbate (2 mM) and N-methyl phenazinium methyl sulfate (PMS) (5 μM). Similar results were obtained with both reductants. The concentrations of ba3 and O2 after the mixing were 20 and ~600 μM, respectively.

Time-resolved resonance Raman spectra were measured using a home-made continuous flow apparatus [11]. Raman scattering was excited by the 413.1 nm line of a Kr+ laser (Spectraphysics, BeamLock 2080), and collected into a Spex 1.25 m polychromator equipped with a charge-coupled device detector (Princeton Instruments, Model 1100PB). The spectra were calibrated with the Raman bands of metMb, for which the accurate band positions were determined by independent experiments using a spinning cell system and indene as the Raman frequency standard.

3. Results

3.1 Stopped Flow Optical Absorption Measurements

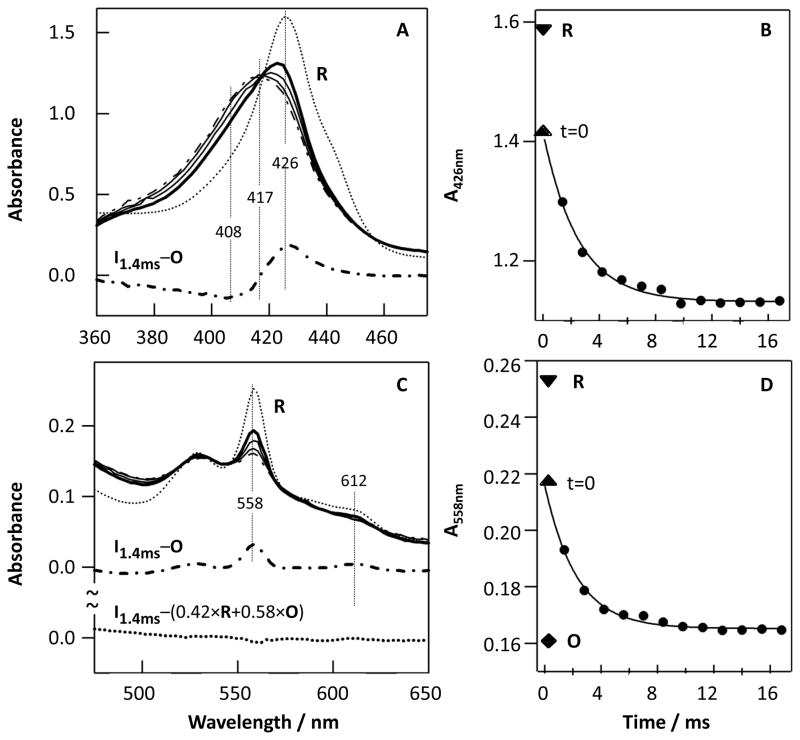

As shown in Fig. 1A and C, the fully reduced ba3 enzyme (R) has a Soret band at 426 nm with a shoulder at ~440 nm (from the low spin heme b and the high spin heme a3, respectively) and a visible band at 558 nm (from reduced heme b) [3, 5]. The weak shoulder at ~590 nm, attributed to a low spin heme a3 species, suggest a micro heterogeneity in the enzyme sample [12], perhaps due to the partial absence of CuB resulting in formation of bis-His heme a3 [6]. Immediately following the mixing of the fully reduced enzyme (R) with O2-saturated buffer, the Soret band shifted to ~422 nm, and decreased in intensity, along with a decrease in intensity of the visible band at 558 nm. As the reaction progressed, the 422 nm band shifted to 417 nm, accompanied by further reduction of the intensity of the visible band, cumulating in a spectrum similar to that of the fully oxidized enzyme [13], O, at 280 ms. The small residual intensity at 558 nm indicates that the reaction has not yet reached completion. The difference spectrum obtained by subtracting the O spectrum from the 1.4 ms spectrum has a peak and trough at 426 and 408 nm, respectively, which was assigned by Giuffre et al., as the F minus O difference spectrum[2].

Figure 1.

Optical absorption spectra obtained following 1:1 mixing of the fully reduced ba3 (R) with O2-saturated buffer in a stopped-flow instrument (A, C) and the associated kinetic traces at 426 nm (B) and 558 nm (D). The spectra in (A) and (C) were obtained at 1.4 ms (thick solid line), 2.8 and 7.0 ms (thin solid lines) and 280 ms (dot-dashed line); the thick dot-dashed lines were calculated from I1.4ms minus O, where I1.4ms and O are the intermediate and oxidized spectra obtained at 1.4 and 280 ms, respectively. The thin dotted lines in (A) and (C) are the R state spectrum. The thick dotted line in (C) was calculated from I1.4ms-(0.42×R+0.58×O). The solid traces in (B) and (D) are the single exponential fits to the data; the upright and inverted triangles indicate the absorbance level at t=0 (obtained by extrapolating the kinetic traces back to time zero) and that of the R state, respectively. The diamond in (D) is the absorbance level of the O state obtained at 280 ms.

The kinetic traces at 426 nm (λmax of the R state) and 558 nm (λmax of the reduced heme b) shown in Fig. 1B and D are best-fitted with a single exponential function with a rate constant of 400 s−1. In both cases, the absorbance at t=0 (the upright triangle) obtained by extrapolating the kinetic trace to time zero is lower than that of the R state (the inverted triangle), indicating the existence of an additional kinetic phase unresolved with our instrument. However, the amplitude of the missing phase cannot be precisely determined with our current instrumentation. These optical changes, occurring after 1.4 ms, may be compared to those reported by Sundi et al. between 10−6 and 10 −2s [14].

3.2 Resonance Raman Measurements

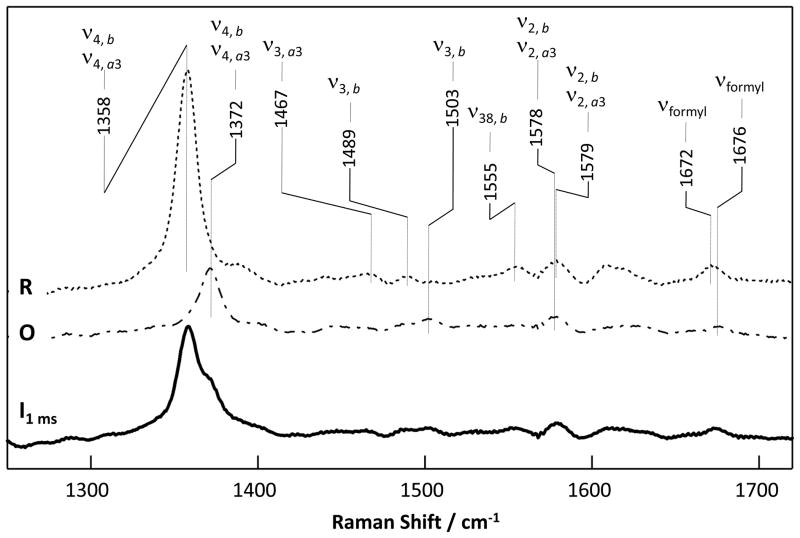

To further explore the identity of the 1.4 ms intermediate, we measured the RR spectrum (Fig. 2) of the sample at 1.0 ms following the initiation of the oxygen reaction in a home-made continuous-flow mixer [11]. The RR bands of ba3 have been previously assigned [15, 16]. Among them, a porphyrin core vibration mode in the 1350–1400 cm−1 region, ν4, is especially useful for the determination of the oxidation states of the two heme centers. The ν4 mode, which is sensitive to the electron density of the heme irons, exhibits systematic frequency shifts in the following order: ferrous < ferric < ferryl (a34+=O2−) [17–19]. As a reference, we measured the ν4 bands of the ferryl derivative of the bovine aa3 oxidase, with 413.1 nm excitation, the same as that used to obtain the spectrum of the ba3 intermediate. The data show that the frequency of the ν4 band of the ferryl species derived from either mixed valence F or mixed valence P intermediate (each of which is comprised of a ferryl heme a3 (a3+a34+=O2−) [20, 21] and a ferric heme a) was higher than that of the oxidized enzyme (Fig. S2 in Supplementary Data).

Figure 2.

The RR spectrum obtained at 1 ms following the mixing of the fully reduced ba3 (R) with O2-saturated buffer. The RR spectra of the R (dotted line) and O (dot-dashed line) states of the enzyme are shown as references. The excitation wavelength was 413.1 nm.

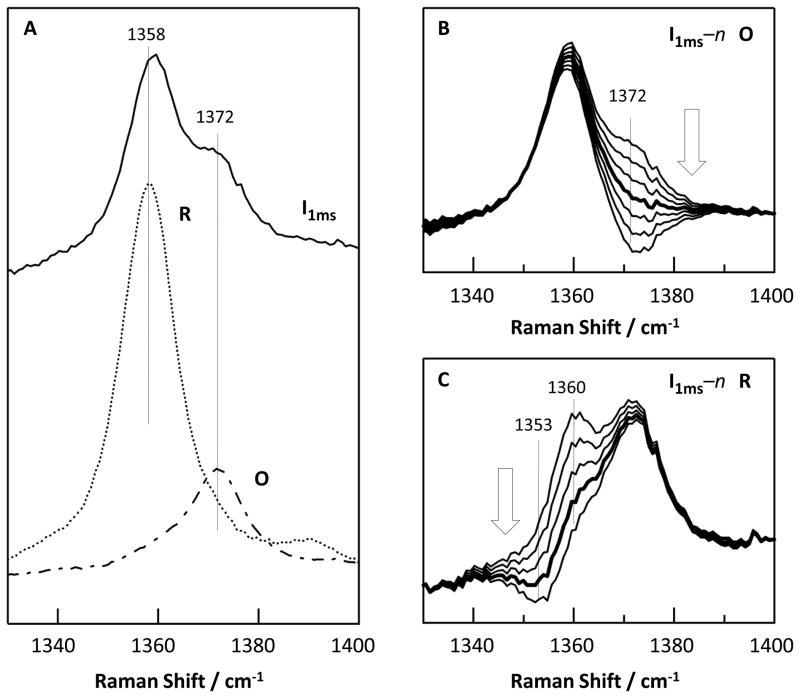

The RR spectrum of the intermediate at 1.0 ms exhibits ν4 modes at ~1358 and ~1372 cm−1 (Fig. 3A), which are assigned to the R and O states of the enzyme, respectively. The ν4 mode assigned to the O state is identical to that of the oxidized enzyme shown in Fig. 3A, and is similar to that of the published data [16]. To confirm the assignment of the 1372 cm−1 mode to the O state, we calculated a series of difference spectra by subtracting the O spectrum from the 1 ms spectrum with various ratios (Fig. 3B). None of these difference spectra showed derivative-like shapes as that observed in the O minus F spectrum of the bovine aa3 enzyme (Fig. S2 in Supplementary Data), indicating that the intermediate is not F or any other ferryl species. Consistent with the absence of evidence for a ferryl species, no oxygen sensitive lines could be detected in the low frequency RR spectrum of the intermediate based on 16O2-18O2 isotopic substitution experiments (Fig. S3 in Supplementary Data).

Figure 3.

The ν4 bands of the 1 ms intermediate state (solid line) as compared to the R (dotted line) and O (dot-dashed line) states of ba3 (A) and the simulated spectra obtained by subtracting increasing amount of the O or R spectrum from the 1 ms RR spectrum (as indicated by the arrows) (B–C). The thick line in (B) shows the best simulated spectrum with the spectral contribution from the O state totally canceled. The thick line in (C) demonstrates a shift of the ν4 band to higher frequency in the 1 ms spectrum with respect to that of the equilibrium R state.

In contrast to the behavior of the oxidized component, if the R spectrum is subtracted from the 1 ms spectrum with various ratios (Fig. 3C), derivative-like shapes (with peak and trough at 1360 and 1353 cm−1, respectively) emerge. The fact that a clean cancellation of the ν4 band at 1358 cm−1 could not be achieved via the subtraction procedure reveals the presence of a new species, which exhibits its ν4 band at a slightly higher frequency than the ν4 of the R state at 1358 cm−1. It should be noted that the derivative shape indicates a small band shift of ν4 to higher frequency but the positions of the peak and trough in the spectrum do not indicate a 7 cm−1 shift but rather they depend on the center frequencies, bandwidths and intensities of the original bands [22]. Nonetheless, it is certain that the ν4 frequency of the intermediate is close to that of the equilibrium R state, indicating that the hemes remain reduced but, importantly, their structures are perturbed.

Additional information on the properties of the mixture of the O state and the perturbed R state present at ~1 ms is provided by the other lines in the resonance Raman spectrum (Fig. 2). The spectrum may be simulated by a mixture of the equilibrium R and O states with one interesting difference. The high spin marker line ν3 from reduced heme a3 at 1470 cm−1 is absent in the intermediate spectrum indicating that the structure of the R state in the intermediate has low s pin character.

4.0 Discussion

4.1 Assignment of the intermediate structure

Taken together the data reported here suggest that the 1 ms intermediate is a mixture of the fully reduced enzyme with a perturbed R structure (named R′ hereafter) and the fully oxidized enzyme (O), without any evidence for the formation of ferryl species. The data shown in Fig. 1A support this conclusion as it indicates that heme b in the intermediate is partially oxidized, while the F species of the ba3 enzyme has been shown to have a reduced rather than an oxidized heme b [3, 5]. Moreover, the 610 nm band was not observable in the 1.4 ms minus O spectrum shown in Fig. 1C, despite the fact that in the F minus O spectrum obtained from CO photolysis measurements [3, 5] the intensity of the 610 nm band is about 70% of the 558 nm band originating from heme b2+ [3]. It is noted that although the 1.4 ms spectrum has a weak shoulder at ~610 nm, it is assigned to the 612 nm band of the residual R state.

As an additional test, we simulated the visible spectrum of the intermediate by a linear combination of the R and O spectra. The best fitted spectrum, accurately reproduced the intermediate spectrum, with negligible residuals (Fig. 1C). Thus, the difference between this linear combination and the 1.4 ms spectrum (thick dotted trace in Fig. 1C) is essentially featureless, confirming that the 1.4 ms minus O state spectrum (Fig. 1A) can be fully accounted for by an R′ minus O difference spectrum, if the visible spectrum of R′ is approximately the same as that of R. In summary, our experimental findings show that the R state ba3 decayed to the O state upon reacting with O2 without detectable build up of discrete intermediates in the stopped-flow time range. Although there were minor differences, the spectroscopic characteristics of the reduced state (R′) present at ~1 ms were very close to those of the initial R state.

The observation of two components in the oxygen reaction at 1 ms, one of which is a perturbed reduced state indicates that the O2 has interacted with the enzyme in R′ and is likely trapped in a docking site along its pathway to the heme a3 iron atom. In addition to the obvious possibility of CuB, other potential ligand docking sites have been identified in the past by crystallographic studies of Xe and Kr binding and by CO photolysis studies. In the latter experiments, reported by Varotsis and coworkers, B0 and B1 CO docking sites were detected, analogous to such sites reported in myoglobin [23]. Interestingly, the penultimate O2 binding site (Xe1) determined from the crystallographic studies [24] lies close (~5 Å) from one of the heme propionates and accordingly could be the same site as that determined in the CO photolysis measurements[1].

To assess each of the potential binding sites we consider the properties of the putative O2 channel and the potential docking sites that lie in the channel. Crystallographic studies determined that O2 could enter through a large unrestricted hydrophobic tunnel that extended all the way into the space between the heme a3 iron and CuB [24, 25]. Therefore the O2 would have no obstruction for gaining access to the binuclear center [25]. As the non-CuB putative docking sites are located along this pathway, their kinetics properties must be considered. The CO off-rate kinetics of the B1 and B0 sites were determined by Varotsis and coworkers to be 85 and 110 μs, respectively [23]. Therefore, the CO off-rates of the docking sites (~100 μs) are much faster than the decay of R′ (~2.5 ms). On the other hand it is well documented that CO binds to CuB and forms a metastable adduct in ba3 in which the transfer rate of CO from CuB to the heme iron is quite slow (35 ms, k2=28.6 s−1) [1]. This is slower than the observed rate of 400 s−1 (2.5 ms) in our data. Therefore our observed rate is too slow as compared to the non-CuB sites and too fast as compared to the CuB site. However, in bovine CcO the transfer rate for CO from CuB to heme a3 (k2) is ~103 s−1 [26] but it is much faster for O2 (~ 105 s−1) [27, 28]. By comparison, we would expect that the O2 transfer rate in ba3 would also be significantly faster than the CO transfer rate, making CuB the most likely doc king site for the O2.

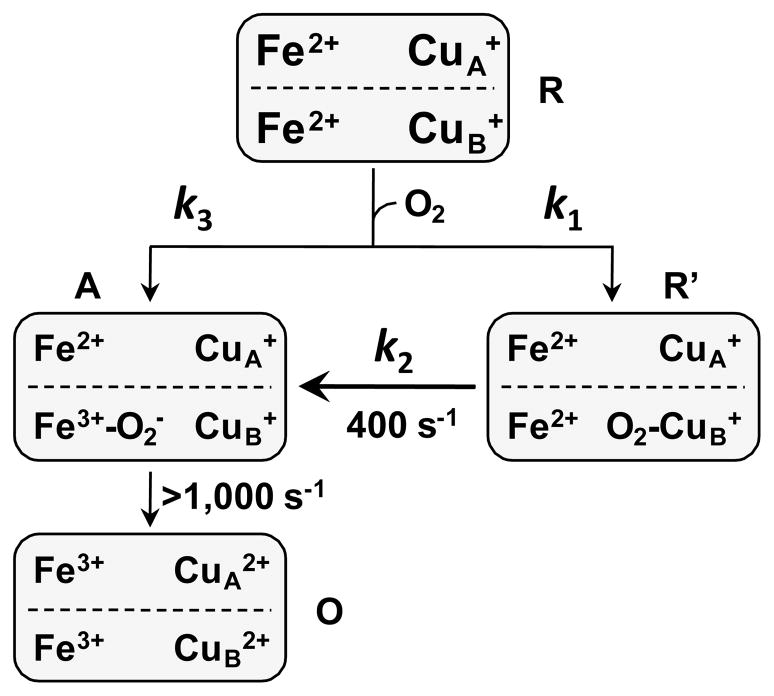

4.2 Reaction Scheme

Based on the above considerations we postulate that CuB is the metastable binding site for O2 and the oxygen reaction follows the bifurcated reaction mechanism illustrated in Figure 4. Following the initiation of the reaction, in one fraction of the ba3 enzyme, O2 binds rapidly to heme a3 (with a rate constant of k3), leading to an O2-complex (the A state), which rapidly decays to the oxidized O state (with a rate constant >1,000 s−1), accounting for the missing phase in the stopped-flow data shown in Fig. 1. In the other fraction of the enzyme, O2 binds to CuB, with a rate constant of k1, which leads to a metastable intermediate, R′, with spectroscopic properties slightly perturbed from those of the equilibrium R state. The R′ state subsequently converts to the A state via an intramolecular ligand transfer from CuB to heme a3, with a rate constant of 400 s−1; the A state ultimately decays to the O state without populating any detectable intermediates. On the basis of this mechanism, the rate-limiting step of the reaction is the intramolecular ligand transfer from CuB to heme a3, manifesting the important role of CuB in regulating the oxygen reaction kinetics of the ba3 enzyme. It is noteworthy that although O2 also binds to CuB in aa3 enzymes [29], due to its short lifetime, its influence on the oxygen reaction kinetics is not as prominent as in ba3.

Figure 4.

The bifurcated oxygen reaction mechanism of the ba3 enzyme.

The structural basis for the two distinct phases of the oxygen reaction of the ba3 enzyme remains to be further investigated. Native gel electrophoresis on ba3 showed only a single band. However, this does not mean that there is no conformational heterogeneity in the ba3 protein, as conformational differences in the region of the active site would not be expected to be separated on a native gel. Indeed, FT-IR studies of the CO-bound ba3 indicate that the heme-CO moiety resides in three distinct conformations [1, 4]. Our preliminary resonance Raman experiments also demonstrate the presence of at least two active site conformers of the CO-bound ba3 (T. Egawa et al., unpublished results). Analogous heme-CO conformers have also been seen in other terminal oxidases, and they are classified into either α or β forms, depending on the frequencies of the iron-CO and C-O stretching modes [30–32]. The relative populations of such two conformers have been correlated with the catalytic activity of the enzyme [32]. Interestingly, in ba3, the multiple structures appear to fall in the range of only the α conformation in the other proteins (T. Egawa et al., unpublished data). MCD studies have also revealed the heterogeneity in the CO-adduct of the ba3 enzyme [12]. Thus the presence of multiple conformations in terminal oxidases is well established and the results reported here demonstrate the functionalconsequences of the heterogeneity.

5. Conclusion

The data reported here indicate that the high affinity of CuB toward O2 plays a pivotal role in regulating the oxygen reaction kinetics of the ba3 enzyme. They also account for the discrepancy in the oxygen reaction kinetic data resulting from stopped-flow mixing and CO-photolysis studies. It is conceivable that, in the photolysis experiments, the photolyzed CO transiently occupies the CuB site [3, 5], and prevents the reaction from being kinetically trapped in the R′ state, thereby accounting for the major phase with a rate of >1,000 s−1. From a physiological point of view, the high affinity of CuB toward O2 in the ba3 enzyme is plausibly beneficial for the survival of the T. thermophilus bacterium under conditions of reduced oxygen tension as it increases the efficiency of the enzyme to utilize O2 for energy production.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health Grants GM074982 and GM098799 to D.L.R. and GM035342 to J.A.F. and the National Science Foundation Grant NSF0956358 to S.-R.Y.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ba3

Cytochrome ba3 from Thermusthermophilus

- RR

Resonance Raman

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Koutsoupakis K, Stavrakis S, Pinakoulaki E, Soulimane T, Varotsis C. Observation of the equilibrium CuB-CO complex and functional implications of the transient heme a3 propionates in cytochrome ba3-CO from Thermus thermophilus. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and time-resolved step-scan FTIR studies. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32860–32866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giuffre A, Forte E, Antonini G, D’Itri E, Brunori M, Soulimane T, Buse G. Kinetic properties of ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus: effect of temperature. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1057–1065. doi: 10.1021/bi9815389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siletsky SA, Belevich I, Jasaitis A, Konstantinov AA, Wikstrom M, Soulimane T, Verkhovsky MI. Time-resolved single-turnover of ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1767:1383–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinakoulaki E, Ohta T, Soulimane T, Kitagawa T, Varotsis C. Simultaneous resonance Raman detection of the heme a3-Fe-CO and CuB-CO species in CO-bound ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Evidence for a charge transfer CuB-CO transition. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22791–22794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400124200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smirnova IA, Zaslavsky D, Fee JA, Gennis RB, Brzezinski P. Electron and proton transfer in the ba(3) oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008;40:281–287. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9157-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Hunsicker-Wang L, Pacoma RL, Luna E, Fee JA. A homologous expression system for obtaining engineered cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus HB8. Protein Expr Purif. 2005;40:299–318. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshikawa S, Choc MG, O’Toole MC, Caughey WS. An infrared study of CO binding to heart cytochrome c oxidase and hemoglobin A. Implications re O2 reactions. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:5498–5508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bickar D, Bonaventura J, Bonaventura C. Cytochrome c oxidase binding of hydrogen peroxide. Biochemistry. 1982;21:2661–2666. doi: 10.1021/bi00540a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji H, Yeh SR, Rousseau DL. Structural characterization of the [Pco/o(2)] compound of cytochrome c oxidase. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:6361–6364. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonomura B, Nakatani H, Ohnishi M, Yamaguchi-Ito J, Hiromi K. Test reactions for a stopped-flow apparatus. Reduction of 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol and potassium ferricyanide by L-ascorbic acid. Anal Biochem. 1978;84:370–383. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi S, Yeh SR, Das TK, Chan CK, Gottfried DS, Rousseau DL. Folding of cytochrome c initiated by submillisecond mixing. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:44–50. doi: 10.1038/nsb0197-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldbeck RA, Einarsdottir O, Dawes TD, O’Connor DB, Surerus KK, Fee JA, Kliger DS. Magnetic circular dichroism study of cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus: spectral contributions from cytochromes b and a3 and nanosecond spectroscopy of CO photodissociation intermediates. Biochemistry. 1992;31:9376–9387. doi: 10.1021/bi00154a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farver O, Chen Y, Fee JA, Pecht I. Electron transfer among the CuA-, heme b- and a3-centers of Thermus thermophilus cytochrome ba3. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:3417–3421. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szundi I, Funatogawa C, Fee JA, Soulimane T, Einarsdottir O. CO impedes superfast O2 binding in ba3 cytochrome oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:21010–21015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008603107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerscher S, Hildebrandt P, Buse G, Soulimane T. The active site structure of ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus studied by resonance raman spectroscopy. Biospectroscopy. 1999;5:S53–63. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6343(1999)5:5+<S53::AID-BSPY6>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oertling WA, Surerus KK, Einarsdottir O, Fee JA, Dyer RB, Woodruff WH. Spectroscopic characterization of cytochrome ba3, a terminal oxidase from Thermus thermophilus: comparison of the a3/CuB site to that of bovine cytochrome aa3. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3128–3141. doi: 10.1021/bi00176a048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chuang WJ, Heldt J, Van Wart HE. Resonance Raman spectra of bovine liver catalase compound II. Similarity of the heme environment to horseradish peroxidase compound II. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14209–14215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitagawa T, Ozaki Y. Infrared and Raman spectra of metalloporphyrins. Struct Bonding. 1987;64:71–114. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spiro TG. Resonance Raman spectroscopy as a probe of heme protein structure and dynamics. Adv Protein Chem. 1985;37:111–159. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Branden G, Gennis RB, Brzezinski P. Transmembrane proton translocation by cytochrome c oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:1052–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitagawa T, Ogura T. Time-resolved resonance Raman study of dioxygen reduction by cytochrome c oxidase. Pure & Appl Chem. 1998;70:881–888. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rousseau DL. Raman difference spectroscopy as a probe of biological molecules. J Raman Spectrosc. 1981;10:94–99. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koutsoupakis C, Soulimane T, Varotsis C. Docking site dynamics of ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36806–36809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luna VM, Chen Y, Fee JA, Stout CD. Crystallographic studies of Xe and Kr binding within the large internal cavity of cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus: structural analysis and role of oxygen transport channels in the heme-Cu oxidases. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4657–4665. doi: 10.1021/bi800045y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu B, Chen Y, Doukov T, Soltis SM, Stout CD, Fee JA. Combined microspectrophotometric and crystallographic examination of chemically reduced and X-ray radiation-reduced forms of cytochrome ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus: structure of the reduced form of the enzyme. Biochemistry. 2009;48:820–826. doi: 10.1021/bi801759a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodruff WH. Coordination dynamics of heme-copper oxidases. The ligand shuttle and the control and coupling of electron transfer and proton translocation. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1993;25:177–188. doi: 10.1007/BF00762859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliveberg M, Malmstrom BG. Reaction of dioxygen with cytochrome c oxidase reduced to different degrees: indications of a transient dioxygen complex with copper-B. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3560–3563. doi: 10.1021/bi00129a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verkhovsky MI, Morgan JE, Wikstrom M. Oxygen binding and activation: early steps in the reaction of oxygen with cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3079–3086. doi: 10.1021/bi00176a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blackmore RS, Greenwood C, Gibson QH. Studies of the primary oxygen intermediate in the reaction of fully reduced cytochrome oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19245–19249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Das TK, Tomson FL, Gennis RB, Gordon M, Rousseau DL. pH-dependent structural changes at the Heme-Copper binuclear center of cytochrome c oxidase. Biophys J. 2001;80:2039–2045. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egawa T, Lin MT, Hosler JP, Gennis RB, Yeh SR, Rousseau DL. Communication between R481 and Cu(B) in cytochrome bo(3) ubiquinol oxidase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2009;48:12113–12124. doi: 10.1021/bi901187u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ji H, Das TK, Puustinen A, Wikstrom M, Yeh SR, Rousseau DL. Modulation of the active site conformation by site-directed mutagenesis in cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. J Inorg Biochem. 2010;104:318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.