Abstract

Direct evaluation of the contribution of somatic hypermutation (SHM) to mucosal immunity has been hampered by the lack of models able to dissociate SHM from class-switch recombination, which are both dependent on the cytidine deaminase AID. A new mouse AID model now demonstrates the critical role of SHM in the control of gut bacteria.

The diversification of immunoglobulin genes is critical for the generation of immune protection. This is particularly true at mucosal sites such as the intestine, which is populated by a large community of commensal bacteria. Mature B cells generate immunoglobulin gene diversity by undergoing somatic hypermutation (SHM) and class-switch recombination (CSR) in the germinal center of lymphoid follicles. SHM introduces point mutations into recombined variable-diversity-joining (V(D)J) exons that encode the antigen-binding V region of immunoglobulins, thereby providing the structural correlate for the selection of high-affinity immunoglobulin mutants by antigen1. In contrast, CSR replaces the μ-chain constant region (Cμ) exon, which encodes immunoglobulin M (IgM), with Cγ, Cα or Cε exons, which encode IgG, IgA or IgE, thereby providing immunoglobulins with new effector functions without changing their specificity for antigen1. Both SHM and CSR require the DNA-editing enzyme AID (activation-induced cytidine deaminase)2. Because of this common reliance on AID and hence the difficulty in dissociating SHM from CSR in mice that lack AID, the specific contribution of SHM to mucosal immunity has remained elusive. In this issue of Nature Immunology, Wei et al. use a mouse model that expresses an SHM-defective but CSR-competent AID molecule to show that SHM is critical for the generation of homeostasis and immunity in the intestine by B cells3.

The interaction between the intestinal mucosa and commensals has been in the limelight in the past decade because of its huge relevance to the biology of both health and disease states. It is now well recognized that commensals establish a symbiotic relationship with the host in the intestine, as they process otherwise indigestible food components, synthesize essential vitamins, stimulate the maturation of the immune system, and form an ecological niche that restricts the growth of pathogenic species4. Conversely, the host provides commensals with a habitat rich in energy derived from the processing of food4. Underlying such peaceful symbiosis is the dynamic process known as homeostasis5, which is carried out by the mucosal immune system to limit microbial penetration without causing inflammation (Fig. 1, left). This is a rather monumental task, given the enormous number of microbes that inhabit the intestine. One strategy for achieving this task is the production of large amounts of highly diversified IgA6. This antibody class generates a first line of defense by virtue of its ability to interact with the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor, an epithelial transporter that shuttles IgA onto the surface of the intestinal mucosa6. The resulting secretory IgA has mucophilic properties and promotes immune exclusion by recognizing microbes and ensnaring them in the mucus to diminish their adhesion to epithelial cells6. It also suppresses the expression of proinflammatory antigens on commensal bacteria and regulates the appropriate composition of microbial communities in specific mucosal districts6. Although a diversified mucosal IgA response through SHM has been suggested to be important in achieving these functions7,8, the role of SHM in mucosal immune defense has not been directly evaluated because of the lack of models able to dissociate SHM from CSR in vivo.

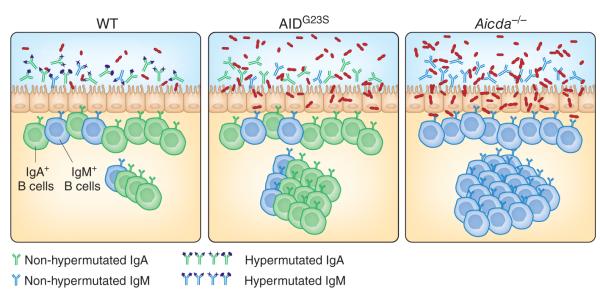

Figure 1.

Lack of SHM impairs mucosal homeostasis and immunity. In wild-type (wT) mice (left), AID-mediated antibody diversification via CSR and SHM generates a diversified mucosal repertoire comprising IgA (green) and, to a lesser extent, IgM (blue), which regulates the composition of the local commensal microbiota. Mice expressing the CSR-competent but SHM-defective mutant AIDG23S molecule (middle) produce normal amounts of unmutated IgA and IgM, which cannot efficiently recognize the intestinal microflora, thereby causing aberrant expansion of and more epithelial adhesion of certain bacterial species. More penetration of these bacteria across the epithelial barrier drives the hyperactivation of mucosal lymphoid follicles, including Peyer’s patches. Similar but more profound abnormalities are present in AID-deficient (Aicda–/–) mice (right), which show profound defects in both CSR and SHM and hence express only unmutated IgM.

On the basis of the idea that SHM and CSR probably require the interaction of different targeting cofactors with different domains of AID9, Wei et al. analyze mice expressing a knock-in mutation of the gene encoding AID resulting in an AIDG23S mutant with defective SHM activity but largely intact CSR activity in vitro9. These AIDG23S mice have severe defects of SHM in both the Peyer’s patches and lamina propia under steady-state conditions. Such defects are accompanied by hyperplasia of the Peyer’s patches (Fig. 1, middle), a phenotype reminiscent of that of AID-deficient mice7 (Fig. 1, right). These abnormalities are attributable neither to altered V(D)J recombination (an AID-independent process that generates antigen-recognition diversity in bone marrow B cells) nor to altered CSR. Indeed, B cells from AIDG23S mice show no skewed V(D)J gene use and produce normal amounts of class-switched antibodies systemically and at mucosal sites of entry, which permits selective evaluation of the role of SHM in mucosal immunity.

Like AID-deficient mice7, AIDG23S mice develop follicular hyperplasia in Peyer’s patches as a result of excessive activation of the local immune system by the microbiota (Fig. 1, right). Consistent with that, AIDG23S mice have aberrant expansion of anaerobic bacteria in the small intestine (Fig. 1, middle) similar to that reported before for AID-deficient mice7. Treatment with antibiotics to eliminate most gut microbes leads to less follicular hyperplasia, which suggests that the altered microbiota causes more antigenic stimulation of mucosal germinal centers. These data provide compelling evidence that SHM is essential for the restraint of microbial overgrowth and regulation of mucosal homeostasis. Wei et al. go one step further to show that the lack of SHM also impairs the integrity of the mucosal barrier3. Indeed, the intestine of AIDG23S mice becomes more susceptible to invasion by pathogenic bacteria and microbial toxins, which indicates that SHM is also important for mucosal immunity.

The findings noted above highlight the idea that the commensal microbiota exerts a constant pressure on mucosal B cells to diversify their immunoglobulin V(D)J gene repertoire through SHM. Such a diversification process is continuously ongoing and much needed for the maintenance of an intact mucosal barrier. Interestingly, a reversible monocolonization system has been used to demonstrate that high-titer intestinal IgA responses can occur independently of continuous stimulation of the intestinal immune system by commensal bacteria10. However, the IgA antibodies produced in that system show limited diversity of their V(D)J genes, which again suggests that SHM requires a diverse microbiota for full diversification of IgA. Of note, intestinal IgA responses are probably driven by a restricted subset of commensal bacteria able to gain access to antigen-sampling microfold cells and dendritic cells. Indeed, Wei et al. observe ‘preferential’ expansion of Clostridium species in the intestinal biopsies of several AIDG23S mice examined3. Clostridiales are closely related to segmented filamentous bacteria11, which probably represent a major source of antigen for the development of intestinal IgA responses because of their ability to adhere to the intestinal epithelium and gain access to antigen-sampling cells. That possibility is further supported by findings showing that segmented filamentous bacteria are the predominant species that shape intestinal helper T cell responses12, which must provide cognate help to B cells during T cell–dependent IgA production in response to invasive pathogens.

The microbiota is a dynamic consortium specific to each individual organism, and the intestinal IgA response constantly adapts to the composition of this consortium at any given point in time10. This reflects a built-in algorithm for control of the size of the mucosal IgA response, perhaps due to the limited space available to IgA-secreting plasma cells in the intestinal lamina propria. Thus, it is conceivable that SHM diversifies IgA only in response to the adherent fraction of the human microbiota, which allows mucosal B cells to ignore the vast majority of nonadherent microbes that may instead be handled by other, less-specific defense mechanisms, including polyreactive IgA from unmutated B cells as well as mucus and antimicrobial peptides from mucosal epithelial cells and cells of the innate immune response. In this manner, mucosal B cells would achieve sufficient IgA diversity in a context of the ongoing clonal expansion needed to achieve sufficient numbers of IgA-producing cells.

AIDG23S mice release more IgA into the stool than do wild-type mice but are unable to generate intestinal protection against cholera toxin, which further suggests that SHM is more important than CSR for the generation of antigen-specific immunity in the intestine. Perhaps the functional dominance of SHM over CSR at mucosal sites may reflect the fact that SHM arose before CSR during the evolution of the adaptive immune system. Indeed, SHM exists in both higher and lower vertebrates, including fish, whereas CSR is found only in higher vertebrates, including amphibians and mammals13. The AIDG23S knock-in mouse created by Wei et al.3 constitutes a useful tool for the study of the function of SHM in other mucosal districts such as the respiratory mucosa, where the antibody composition is more heterogeneous, encompassing extremely hypermutated isotypes such as IgD, at least in humans14,15. The achievement of such goals, however, must await more complete elucidation of the microbiota that inhabit extraintestinal mucosal districts.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contributor Information

Kang Chen, The Immunology Institute, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York, USA..

Andrea Cerutti, The Immunology Institute, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York, USA, and the Catalan Institute for Research and Advanced Studies, L’Institut Municipal d’Investigació Mèdica Hospital del Mar, Barcelona Biomedical Research Park, Barcelona, Spain. acerutti@imim.es.

References

- 1.Honjo T, Kinoshita K, Muramatsu M. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002;20:165–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.090501.112049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muramatsu M, et al. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei M, et al. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:264–270. doi: 10.1038/ni.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macpherson AJ, Harris NL. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:478–485. doi: 10.1038/nri1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sansonetti PJ. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerutti A, Rescigno M. Immunity. 2008;28:740–750. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagarasan S, et al. Science. 2002;298:1424–1427. doi: 10.1126/science.1077336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki K, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:1981–1986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307317101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shinkura R, et al. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:707–712. doi: 10.1038/ni1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hapfelmeier S, et al. Science. 2010;328:1705–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1188454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snel J, et al. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1995;45:780–782. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaboriau-Routhiau V, et al. Immunity. 2009;31:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flajnik MF. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:688–698. doi: 10.1038/nri889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu YJ, et al. Immunity. 1996;4:603–613. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80486-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen K, et al. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:889–898. doi: 10.1038/ni.1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]