Abstract

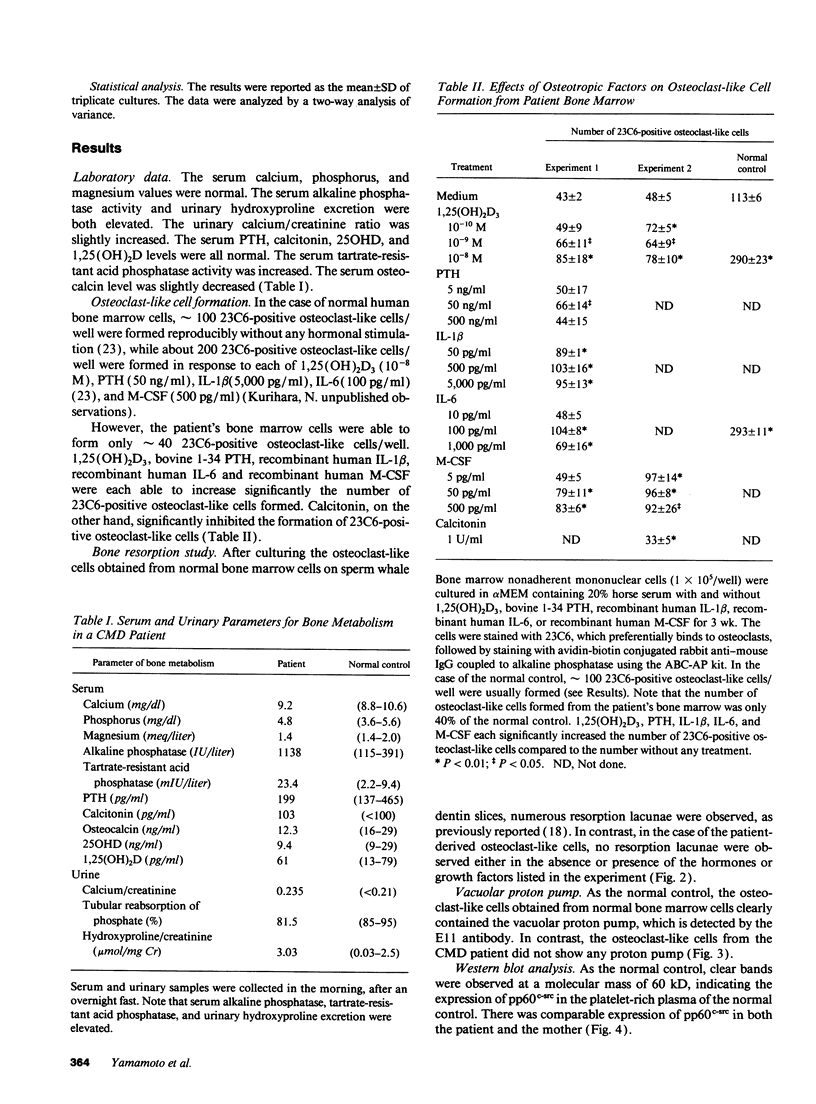

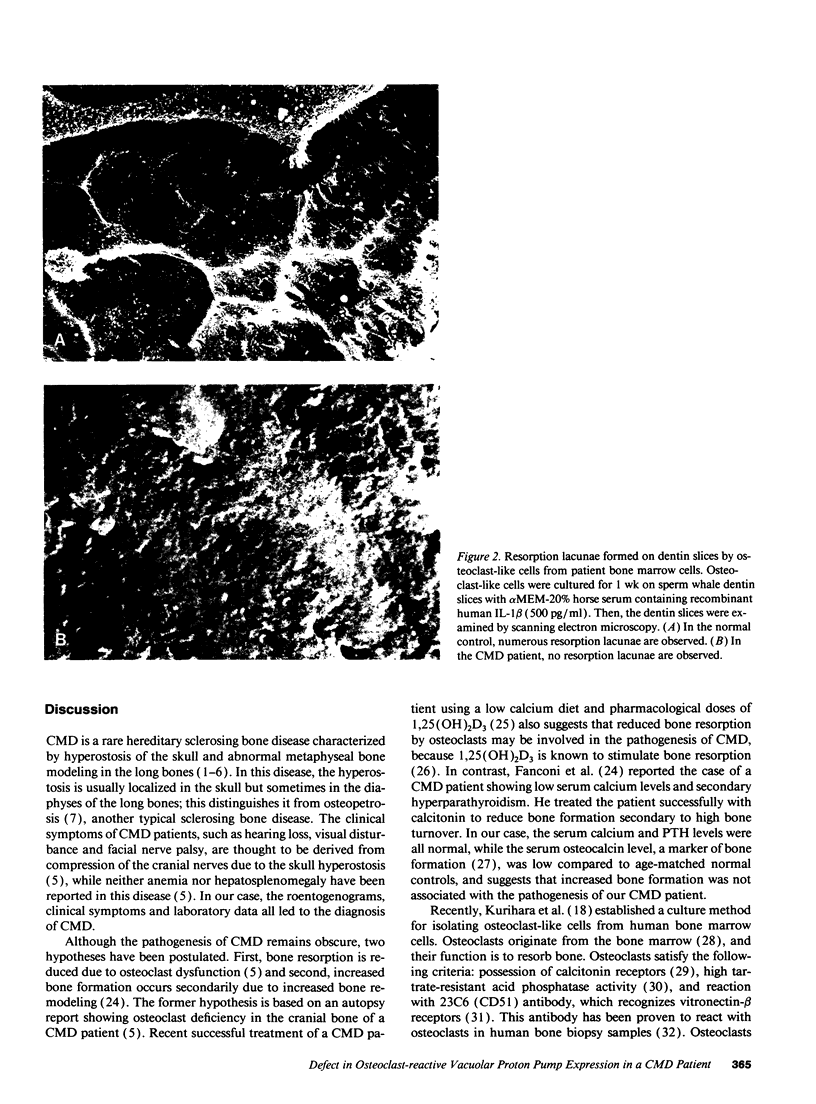

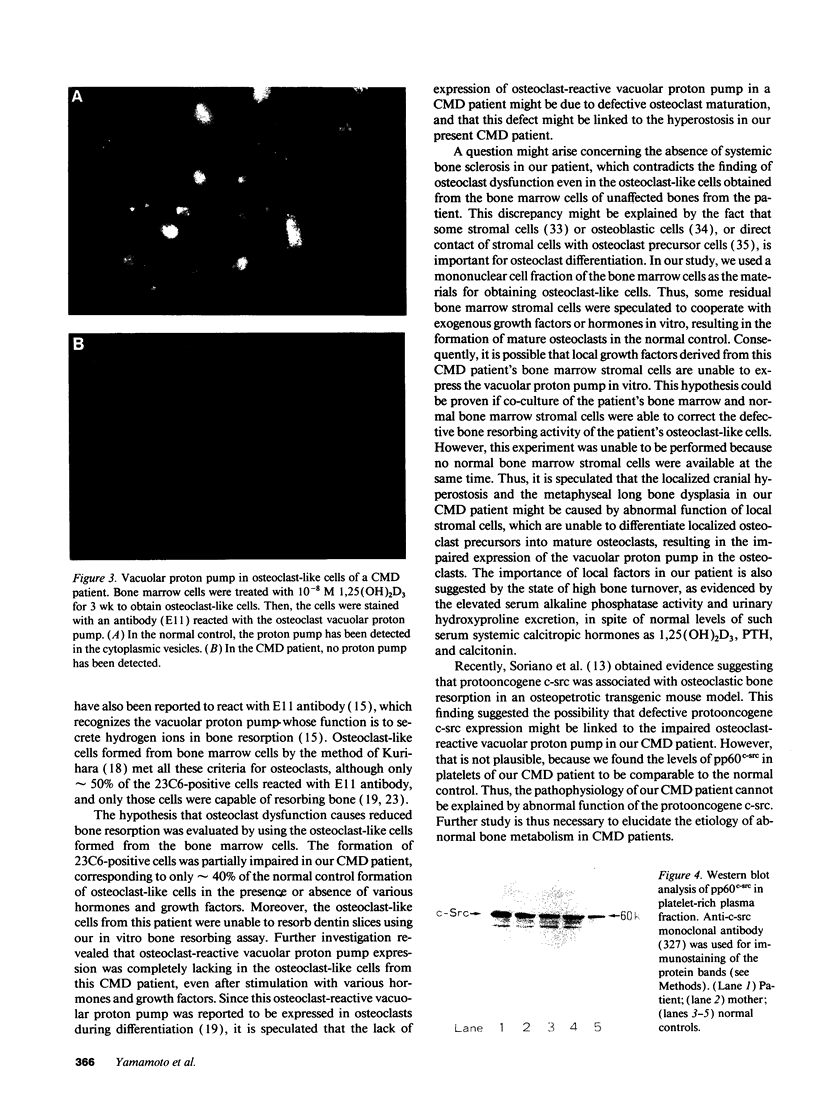

Craniometaphyseal dysplasia (CMD) is a rare craniotubular bone dysplasia transmitted in autosomal dominant or recessive form. This disease is characterized by cranial bone hyperostosis and deformity of the metaphyses of the long bones. Using osteoclast-like cells formed from patient bone marrow cells, we investigated the pathophysiology of CMD in a 3-yr-old patient. Untreated bone marrow cells from the patient differentiated into osteoclast-like cells in vitro. These cells were shown to have vitronectin beta-receptors using a specific monoclonal antibody, i.e., 23C6 (CD51), which reacts with osteoclasts in human bone biopsy samples. However, the number of these osteoclast-like cells formed from the patient's bone marrow was only 40% of the normal controls. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin-D3, bovine 1-34 parathyroid hormone, recombinant human interleukin-1 beta, recombinant human interleukin-6, or recombinant human macrophage colony-stimulating factor significantly increased, while salmon calcitonin significantly inhibited, the number of osteoclast-like cells. However, these cells could not resorb sperm whale dentin slices and lacked the osteoclast-reactive vacuolar proton pump as evidenced by a monoclonal antibody (E11). Western blot analysis using a monoclonal antibody to pp60c-src (327) revealed that protooncogene c-src expression by the platelets of the CMD patient was comparable to the normal control. These data suggest that: (a) the hyperostosis and the metaphyseal long bone deformity in the present CMD patient might be explained by osteoclast dysfunction due to impaired expression of the osteoclast-reactive vacuolar proton pump; and (b) a protooncogene c-src was not associated with the pathogenesis of the present CMD patient.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blair H. C., Teitelbaum S. L., Ghiselli R., Gluck S. Osteoclastic bone resorption by a polarized vacuolar proton pump. Science. 1989 Aug 25;245(4920):855–857. doi: 10.1126/science.2528207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. P., Delmas P. D., Malaval L., Edouard C., Chapuy M. C., Meunier P. J. Serum bone Gla-protein: a specific marker for bone formation in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Lancet. 1984 May 19;1(8386):1091–1093. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92506-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J. A., Runge K. Avian pp60c-src is more active when expressed in yeast than in vertebrate fibroblasts. Oncogene Res. 1987 Sep-Oct;1(4):297–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J., Warwick J., Totty N., Philp R., Helfrich M., Horton M. The osteoclast functional antigen, implicated in the regulation of bone resorption, is biochemically related to the vitronectin receptor. J Cell Biol. 1989 Oct;109(4 Pt 1):1817–1826. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanconi S., Fischer J. A., Wieland P., Giedion A., Boltshauser E., Olah A. J., Landolt A. M., Prader A. Craniometaphyseal dysplasia with increased bone turnover and secondary hyperparathyroidism: therapeutic effect of calcitonin. J Pediatr. 1988 Apr;112(4):587–591. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix R., Cecchini M. G., Hofstetter W., Elford P. R., Stutzer A., Fleisch H. Impairment of macrophage colony-stimulating factor production and lack of resident bone marrow macrophages in the osteopetrotic op/op mouse. J Bone Miner Res. 1990 Jul;5(7):781–789. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650050716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattersley G., Chambers T. J. Calcitonin receptors as markers for osteoclastic differentiation: correlation between generation of bone-resorptive cells and cells that express calcitonin receptors in mouse bone marrow cultures. Endocrinology. 1989 Sep;125(3):1606–1612. doi: 10.1210/endo-125-3-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton M. A., Lewis D., McNulty K., Pringle J. A., Chambers T. J. Monoclonal antibodies to osteoclastomas (giant cell bone tumors): definition of osteoclast-specific cellular antigens. Cancer Res. 1985 Nov;45(11 Pt 2):5663–5669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C. C., Jr, Lavy N., Lord T., Vellios F., Merritt A. D., Deiss W. P., Jr Osteopetrosis. A clinical, genetic, metabolic, and morphologic study of the dominantly inherited, benign form. Medicine (Baltimore) 1968 Mar;47(2):149–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key L. L., Jr, Volberg F., Baron R., Anast C. S. Treatment of craniometaphyseal dysplasia with calcitriol. J Pediatr. 1988 Apr;112(4):583–587. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara N., Civin C., Roodman G. D. Osteotropic factor responsiveness of highly purified populations of early and late precursors for human multinucleated cells expressing the osteoclast phenotype. J Bone Miner Res. 1991 Mar;6(3):257–261. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650060307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara N., Gluck S., Roodman G. D. Sequential expression of phenotype markers for osteoclasts during differentiation of precursors for multinucleated cells formed in long-term human marrow cultures. Endocrinology. 1990 Dec;127(6):3215–3221. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-6-3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsich L. A., Lewis A. J., Brugge J. S. Isolation of monoclonal antibodies that recognize the transforming proteins of avian sarcoma viruses. J Virol. 1983 Nov;48(2):352–360. doi: 10.1128/jvi.48.2.352-360.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald B. R., Takahashi N., McManus L. M., Holahan J., Mundy G. R., Roodman G. D. Formation of multinucleated cells that respond to osteotropic hormones in long term human bone marrow cultures. Endocrinology. 1987 Jun;120(6):2326–2333. doi: 10.1210/endo-120-6-2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks S. C., Jr, Schneider G. B. Transformations of osteoclast phenotype in ia rats cured of congenital osteopetrosis. J Morphol. 1982 Nov;174(2):141–147. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051740203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks S. C., Jr, Walker D. G. The hematogenous origin of osteoclasts: experimental evidence from osteopetrotic (microphthalmic) mice treated with spleen cells from beige mouse donors. Am J Anat. 1981 May;161(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001610102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millard D. R., Jr, Maisels D. O., Batstone J. H., Yates B. W. Craniofacial surgery in craniometaphyseal dysplasia. Am J Surg. 1967 May;113(5):615–621. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(67)90307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nada S., Okada M., MacAuley A., Cooper J. A., Nakagawa H. Cloning of a complementary DNA for a protein-tyrosine kinase that specifically phosphorylates a negative regulatory site of p60c-src. Nature. 1991 May 2;351(6321):69–72. doi: 10.1038/351069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuka K., Miki T., Nishizawa Y., Tabata T., Inoue T., Morii H., Ogata E. Circulating bone Gla protein in end-stage renal disease determined by newly developed two-site immunoradiometric assay. Contrib Nephrol. 1991;90:147–154. doi: 10.1159/000420137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penchaszadeh V. B., Gutierrez E. R., Figueroa E. Autosomal recessive craniometaphyseal dysplasia. Am J Med Genet. 1980;5(1):43–55. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320050107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M. W., Altman D. H. Familial metaphyseal dysplasia. Review of the clinical and radiologic feature of Pyle's disease. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1967 Mar;6(3):143–149. doi: 10.1177/000992286700600309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPRANGER J., PAULSEN K., LEHMANN W. DIE KRANIOMETAPHYSAERE DYSPLASIE (PYLE) Z Kinderheilkd. 1965 Jun 2;93:64–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheven B. A., Visser J. W., Nijweide P. J. In vitro osteoclast generation from different bone marrow fractions, including a highly enriched haematopoietic stem cell population. Nature. 1986 May 1;321(6065):79–81. doi: 10.1038/321079a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P., Montgomery C., Geske R., Bradley A. Targeted disruption of the c-src proto-oncogene leads to osteopetrosis in mice. Cell. 1991 Feb 22;64(4):693–702. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90499-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro P. C., Hamersma H., Beighton P. Radiology of the autosomal dominant form of craniometaphyseal dysplasia. S Afr Med J. 1975 May 17;49(21):839–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart P. J., Stern P. H. Vertebral bone resorption in vitro: effects of parathyroid hormone, calcitonin, 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3, epidermal growth factor, prostaglandin E2, and estrogen. Calcif Tissue Int. 1987 Jan;40(1):21–26. doi: 10.1007/BF02555724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N., Akatsu T., Udagawa N., Sasaki T., Yamaguchi A., Moseley J. M., Martin T. J., Suda T. Osteoblastic cells are involved in osteoclast formation. Endocrinology. 1988 Nov;123(5):2600–2602. doi: 10.1210/endo-123-5-2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N., Yamana H., Yoshiki S., Roodman G. D., Mundy G. R., Jones S. J., Boyde A., Suda T. Osteoclast-like cell formation and its regulation by osteotropic hormones in mouse bone marrow cultures. Endocrinology. 1988 Apr;122(4):1373–1382. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-4-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udagawa N., Takahashi N., Akatsu T., Sasaki T., Yamaguchi A., Kodama H., Martin T. J., Suda T. The bone marrow-derived stromal cell lines MC3T3-G2/PA6 and ST2 support osteoclast-like cell differentiation in cocultures with mouse spleen cells. Endocrinology. 1989 Oct;125(4):1805–1813. doi: 10.1210/endo-125-4-1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udagawa N., Takahashi N., Akatsu T., Tanaka H., Sasaki T., Nishihara T., Koga T., Martin T. J., Suda T. Origin of osteoclasts: mature monocytes and macrophages are capable of differentiating into osteoclasts under a suitable microenvironment prepared by bone marrow-derived stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Sep;87(18):7260–7264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiktor-Jedrzejczak W. W., Ahmed A., Szczylik C., Skelly R. R. Hematological characterization of congenital osteopetrosis in op/op mouse. Possible mechanism for abnormal macrophage differentiation. J Exp Med. 1982 Nov 1;156(5):1516–1527. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.5.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka K., Tanaka H., Kurose H., Shima M., Ozono K., Nakajima S., Seino Y. Effect of single oral phosphate loading on vitamin D metabolites in normal subjects and in X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. Bone Miner. 1989 Sep;7(2):159–169. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(89)90073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H., Hayashi S., Kunisada T., Ogawa M., Nishikawa S., Okamura H., Sudo T., Shultz L. D., Nishikawa S. The murine mutation osteopetrosis is in the coding region of the macrophage colony stimulating factor gene. Nature. 1990 May 31;345(6274):442–444. doi: 10.1038/345442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]