Summary

Background and objectives

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is a rare manifestation of IgA nephropathy (IgAN). Clinical characteristics and long-term outcomes of this condition have not yet been explored.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

A multicenter observational study was conducted between January 2000 and September 2010 in 1076 patients with biopsy-proven IgAN from four medical centers in Korea. The primary outcome was a doubling of the baseline serum creatinine concentration.

Results

Of the 1076 patients, 100 (10.2%) presented with NS; complete remission (CR), partial remission (PR), and no response (NR) occurred in 48 (48%), 32 (32%), and 20 (20%) patients, respectively. During the median follow-up of 45.2 months, 24 patients (24%) in the NS group reached the primary endpoint compared with 63 (7.1%) in the non-NS group (P<0.001). The risk of reaching the primary endpoint was significantly higher in the PR (P=0.04) and NR groups (P<0.001) than in the CR group. Among patients with NS, 24 (24%) underwent spontaneous remission (SR). SR occurred more frequently in female patients and in patients with serum creatinine levels ≤1.2 mg/dl and a >50% decrease in proteinuria within 3 months after NS onset. None of the patients with SR reached the primary endpoint and they had fewer relapses during follow-up.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the prognosis of NS in IgAN was not favorable unless PR or CR was achieved. In addition, SR was more common than expected, particularly in patients with preserved kidney function and spontaneous decrease in proteinuria shortly after NS onset.

Introduction

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common form of GN worldwide, comprising 45% of all primary GN cases (1,2). Many studies report that 30%–40% of patients with IgAN reach ESRD within 20 years from apparent disease onset, underscoring that IgAN is not a benign condition (2–4).

In most cases, initial manifestations of IgAN are recurrent episodes of gross hematuria that usually arise after upper respiratory tract infections and asymptomatic microscopic hematuria with or without mild proteinuria. Fewer than 10% of patients present with uncommon features such as ARF or nephrotic syndrome (NS) (5,6). In particular, NS occurs in only 5% of all patients with IgAN (2). Because IgAN is a slowly progressive type of GN and most patients exhibit normal kidney function at the time of diagnosis, nephrotic range proteinuria is usually indicative of severe glomerular damage in advanced decompensated kidney failure (7). Conversely, clinical features of NS, such as heavy proteinuria, generalized edema, and hypoalbuminemia, can be observed in some patients with normal kidney function. This rare condition is reported to behave similarly to minimal change disease (MCD) (8,9). Accordingly, corticosteroids are often prescribed for IgAN patients with NS because of the favorable steroid responsiveness in MCD (9–11). Most studies regarding this unusual condition were published more than two decades ago. In addition, not all cases of NS in IgAN are caused by MCD, and corticosteroid therapy does not always lead to the resolution of heavy proteinuria (12–14). Furthermore, we found that spontaneous remission (SR) of NS in IgAN was common in a recent study (14). However, we were unable to identify factors associated with SR in our single-center study because of the small number of patients in our sample. To address these issues, we conducted a multicenter, retrospective, observational study of 1076 patients with biopsy-proven IgAN. The aims of this study were to examine the clinical features and long-term outcome of IgAN with NS, and to delineate factors associated with SR among NS patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The study sample comprised 1076 patients with biopsy-proven IgAN who were recruited between January 2000 and September 2010 from four medical centers in Korea. All patients had definite pathologic data with predominant mesangial deposition of IgA with at least 1+ on immunofluorescent staining and electron-dense deposits within the mesangium detected by electron microscopy. Exclusion criteria were as follows: aged <18 years (n=26); crescentic GN (n=2); follow-up duration <6 months (n=15); estimated GFR (eGFR) <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (n=29); malignancy (n=3); systemic inflammation, such as Henoch–Schönlein purpura (n=6); or chronic advanced liver disease (n=10).

Data Collection

Using medical records, demographic and clinical data were reviewed retrospectively for age, sex, medical history, presenting symptoms, medications, follow-up duration, time to remission of NS, time to doubling of the baseline serum creatinine levels and ESRD, and responsiveness to treatment. Laboratory data included 24-hour urinary protein excretion, urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR), and serum creatinine, albumin, and total cholesterol levels. The eGFR was calculated using the four-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation (15).

Data for baseline 24-hour urinary protein excretion were available for all 100 patients with NS and for 469 patients with non-NS and UPCR >1.0. Among the remaining 416 patients with non-NS and UPCR ≤1.0, 238 underwent 24-hour urine collection 52.5±14.2 days after diagnosis. However, 178 patients (18.1%) with UPCR ≤0.5 did not have 24-hour urine collection data. Therefore, data for 24-hour proteinuria were available for 807 patients (81.9%).

Renal pathology data included information on the number of glomeruli and the presence of global or segmental sclerosis, foot process effacement, mesangial hypercellularity, endocapillary proliferation, tubular atrophy, and interstitial fibrosis. All cases were graded using the Haas (16) and the Oxford classification systems (17).

Definitions

The definitions for each term in this study were identical to definitions used in our previous study (14). NS was defined as the presence of generalized edema, heavy proteinuria of >3.5 g/d, hypoalbuminemia <3.5 g/dl, and/or hypercholesterolemia. Complete remission (CR) was defined as the absence of proteinuria (UPCR <0.3 g/g) along with the disappearance of edema, normalization of all biochemical findings, and lack of worsening of renal function. SR was used to indicate CR of NS without the use of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents. Partial remission (PR) was defined as a >50% reduction in proteinuria from baseline to <3.5 g/d. No response (NR) was defined as a <50% reduction in proteinuria or an increase in proteinuria with or without renal deterioration. Relapse was defined as the reappearance of significant proteinuria, defined as >1.0 g/d and/or >3+ urinary albumin by the dipstick test.

Study Endpoints

The primary outcome was a doubling of the baseline serum creatinine concentration; secondary outcomes included ESRD and death. A doubling of serum creatinine levels was defined as a sustained, greater than two-fold increase in serum creatinine levels for at least three consecutive measurements.

Statistical Analyses

Variables with normal distributions were expressed as mean ± SD and were compared using the t test or one-way ANOVA. Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests were used to analyze the normality of the distribution of parameters. Nonparametric variables were expressed as median with range and compared using the Mann–Whitney test or Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and compared using the chi-squared test. Cumulative survival curves were derived using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Five patients who were lost to follow-up were considered “censored” in the analyses. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify independent factors for the development of primary or secondary endpoints and SR. Statistical significance was determined as P<0.05. SPSS software (version 15.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

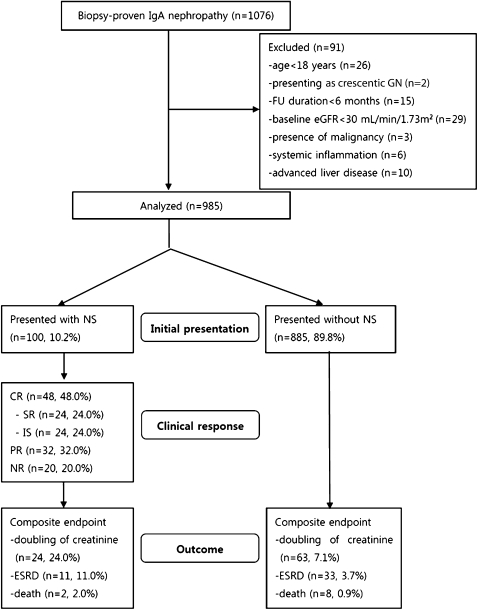

A flow diagram describing the patient sample and exclusions is shown in Figure 1. Baseline characteristics of the 985 patients who met the inclusion criteria are shown in Table 1. Among these patients, NS occurred in 100 (10.2%), with 93 having generalized edema as the first presenting symptom and undergoing renal biopsy within an average of 7 days of symptom onset (1–17). The remaining seven patients initially had microscopic hematuria with minimal proteinuria (UPCR ≤ 0.5 g/g) but presented with acute NS onset during follow-up. Of these patients, four underwent renal biopsy at NS onset, whereas biopsies were performed in the other three patients at 408, 983, and 1021 days before NS development.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient progress and outcomes. From January 2000 through September 2010, IgA nephropathy was diagnosed in 1076 patients, and 100 presented with nephrotic syndrome. FU, follow-up; eGFR, estimated GFR; NS, nephrotic syndrome; CR, complete remission; SR, spontaneous remission; IS, complete remission with the use of immunosuppressant; PR, partial remission; NR, no remission or disease progression.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with IgA nephropathy

| All Patients (N=985) | Nephrotic Syndrome (n=100) | Non-Nephrotic Syndrome (n=885) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 37.7±12.8 | 39.5±15.0 | 37.4±12.5 | 0.12 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 459 (46.6) | 44 (44.0) | 412 (46.6) | 0.83 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 125 (12.7) | 20 (20.0) | 105 (11.9) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 14 (1.4) | 4 (2.9) | 10 (1.1) | 0.08 |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen positivity, n (%) | 31 (3.1) | 7 (7.0) | 24 (2.7) | 0.04 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 123.7±34.8 | 131.9±15.1 | 122.1±34.8 | 0.01 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 76.8±8.9 | 81.1±10.3 | 76.2±8.7 | <0.001 |

| Mean arterial BP (mmHg) | 92.4±14.3 | 98.0±10.9 | 91.8±14.5 | <0.001 |

| Laboratory measurements | ||||

| 24-h protein excretion (g/d) | 1.31 (0.0–16.10) | 5.80 (3.67–16.10) | 1.5 (0.0–3.40) | <0.001 |

| random UPCR (g/g) | 1.05 (0.01–18.20) | 5.74 (3.50–18.20) | 0.98 (0.01–3.74) | <0.001 |

| SCr (mg/dl) | 1.0±0.6 | 1.2±0.4 | 0.9±0.3 | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 84.1±39.1 | 69.4±17.5 | 88.5±32.5 | <0.001 |

| serum albumin (g/dl) | 4.1±0.7 | 2.8±0.6 | 4.2±0.5 | <0.001 |

| total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 190.5±51.3 | 267.0±76.2 | 181.8±39.1 | <0.001 |

| Follow-up duration (mo) | 45.2 (9.0–134.6) | 43.1 (9.0–107.8) | 47.1 (10.0–134.6) | 0.06 |

| Treatments, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| none | 197 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 197 (22.3) | |

| ACEi or ARB | 778 (79.0) | 95 (95.0) | 683 (77.2) | |

| dual blockades | 10 (1.0) | 5 (5.0) | 5 (0.5) | |

| corticosteroids | 144 (14.6) | 65 (65.0) | 79 (8.9) |

All data are expressed as mean ± SD and median (range). UPCR, urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio; SCr, serum creatinine; eGFR, estimated GFR; ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

There were 13 patients who had a UPCR >3.0 g/g in the non-NS group. Among them, three patients had a proteinuria >3.0 g/d (but <3.5 g/d). They were categorized as non-NS because they did not exhibit other NS features such as hypoalbuminemia, edema, or hypercholesterolemia. We also confirmed that nephrotic proteinuria was not ascribed to hypertensive nephrosclerosis because BP was well controlled in 20 patients with a prior history of hypertension and pathologic findings suggesting that hypertensive nephrosclerosis were not found in all NS patients.

Although hyperlipidemia is common in NS, not all patients with NS have hyperlipidemia as previously suggested (18). In our study, only six patients with NS (6%) had total cholesterol levels <200 mg/dl. However, they had edema and hypoalbuminemia and thus were considered to have NS.

Clinical Features of Patients with NS According to Clinical Response

Table 2 shows the clinical features of patients with IgAN with NS according to clinical response. CR was achieved in 48 patients (48%) and PR in 32 patients (32%). However, 20 patients (20%) exhibited minimal response or disease progression (NR).

Table 2.

Analysis of patients who presented with nephrotic syndrome (n=100)

| Complete Remission | Partial Remission | No Response or Progression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous Remission | Immunosuppressant | All | |||

| No. of patients, n (%) | 24 (24.0) | 24 (24.0) | 48 (48.0) | 32 (32.0) | 20 (20.0) |

| Age (yr) | 40.1±15.7 | 37.6±12.1 | 38.9±13.9 | 41.4±13.4 | 37.8±16.8 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 12 (50.0) | 12 (50.0) | 24 (50.0) | 17 (53.1) | 10 (50.0) |

| Presenting symptoms, n (%) | |||||

| generalized edema | 23 (95.8) | 21 (87.5) | 44 (91.7) | 30 (93.7) | 19 (95.0) |

| frothy urinea | 1 (4.2) | 3 (12.5) | 4 (8.3) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (5.0) |

| gross hematuria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 8 (33.3) | 4 (16.7) | 12 (25.0) | 4 (20.0) | 4 (20.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 2 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.2) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (5.0) |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 128.6±12.8 | 132.21±19.73 | 130.4±16.30 | 131.1±15.2 | 136.8±13.4 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 80.3±11.7 | 80.5±10.2 | 80.4±10.9 | 82.6±10.1 | 82.9±8.9 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 96.4±10.9 | 97.7±12.5 | 97.0±11.6 | 97.8±10.9 | 100.7±9.2 |

| Laboratory measurements | |||||

| baseline | |||||

| 24-h proteinuria (g/d) | 5.3 (3.5–14.9) | 5.4 (3.5–15.9) | 5.4 (3.5–15.9) | 6.5 (3.6–16.0) | 5.5 (3.5–9.2) |

| random UPCR (g/g) | 4.2 (3.5–6.7) | 5.9 (3.7–10.2) | 5.2 (3.5–10.2) | 6.0 (3.5–18.2) | 6.2 (3.5–11.2) |

| SCr (mg/dl) | 1.1±0.3 | 1.1±0.4 | 1.1±0.4 | 1.2±0.3 | 1.3±0.4 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 73.3±15.1 | 75.0±18.7 | 74.2±16.9 | 65.3±15.4 | 64.6±20.0 |

| serum albumin (g/dl) | 2.9±0.4 | 2.7±0.6 | 2.8±0.5 | 2.7±0.6 | 2.8±0.5 |

| last follow-up | |||||

| random UPCR (g/g) | 0.2 (0.01–2.2) | 0.2 (0.01–3.8) | 0.2 (0.01–3.8) | 1.6 (0.3–5.2) | 3.2 (1.3–10.2) |

| SCr (mg/dl) | 1.1±0.6 | 1.0±0.5 | 1.1±0.5 | 2.2±0.9 | 6.1±1.8 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 68.8±19.2 | 71.7±20.3 | 70.8±19.7 | 52.9±24.5 | 18.6±11.2 |

| Type of immunosuppressants, n (%) | |||||

| none | 24 (100.0) | 0 | 24 (50.0) | 6 (18.8) | 5 (25.0) |

| steroid only | 0 | 18 (75.0) | 18 (37.5) | 19 (59.3) | 8 (40.0) |

| steroid + cyclosporin | 0 | 6 (25.0) | 6 (12.5) | 6 (18.8) | 4 (20.0) |

| steroid + cyclophosphamide | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0) |

| steroid + mycophenolate mofetil | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.1) | 2 (10.0) |

| Duration of steroid (d) | — | 288 (162–902) | — | 316 (216–978) | 161 (102–405) |

All data are expressed as mean ± SD or median (range). UPCR, urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio; SCr, serum creatinine; eGFR, estimated GFR; —, not applicable.

The presenting symptoms were recorded at the first hospital visit. Generalized edema was not present initially in seven patients, but they had acute onset of NS during follow-up. In fact, they showed generalized edema when NS occurred.

Among patients with NS, 24 (24%) achieved SR without the use of corticosteroids. In these patients, corticosteroids were not immediately administered because rapid and continuous reductions in proteinuria (>50%) occurred after NS onset. In addition, some had uncontrolled diabetes (n=2), gastric ulcers (n=2), pulmonary tuberculosis (n=1), severe osteoporosis (n=2), or hepatitis B infections (n=1). Six patients in the PR group and five in the NR group did not receive corticosteroids because of uncontrolled diabetes (n=1, PR), gastric ulcers with bleeding (n=1, PR), hepatitis B infections (n=2, PR; n=4, NR), or disagreement over the use of steroid treatment (n=2, PR; n=1, NR).

As shown in Table 2, no significant differences in sex, age, BP, serum creatinine levels, or 24-hour proteinuria were observed among the four subgroups. However, class I or II lesions according to the Haas classification were more common in patients with CR than in those with PR or NR (P=0.001), whereas SR occurred in all subclasses of IgAN (Supplemental Table 1).

Long-Term Clinical Outcomes

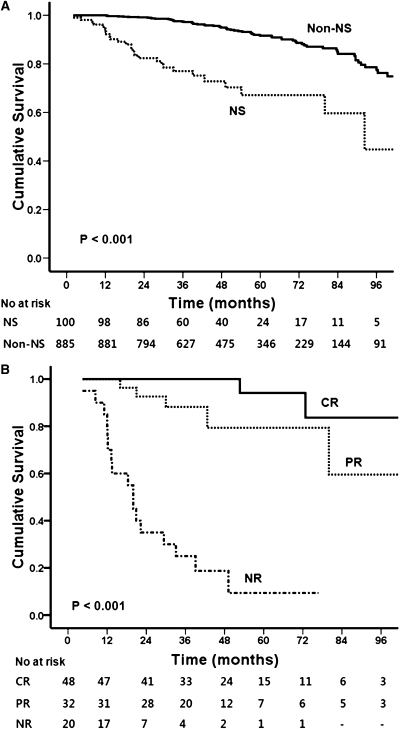

During the median follow-up of 45.2 months (range, 9.0–134.6), 24 patients (24%) in the NS group reached the primary endpoint compared with 63 (7.1%) in the non-NS group (P<0.001). In addition, 11 patients (11.0%) in the NS group progressed to ESRD and two (2.0%) died, compared with 33 (3.7%) with ESRD and 8 (0.9%) deaths in the non-NS group (P<0.001) (Figures 1 and 2A). Increased risks of primary and secondary outcomes were consistently observed for the NS group by different multivariate analysis models (Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of clinical response on renal survival. The primary endpoint was a doubling of the baseline serum creatinine. (A) Risk of reaching the primary outcome was significantly higher in the NS group than in the non-NS group (P<0.001). (B) Patients with NS attaining CR or PR had a favorable outcome compared with patients with NR (P<0.001). NS, nephrotic syndrome; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission; NR, no remission or disease progression.

As shown in Table 3 and Figure 2B, in NS patients, the risk of reaching the primary endpoint was significantly higher in the PR group (hazard ratio [HR], 14.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.14–183.76; P=0.04) and NR group (HR, 215; 95% CI, 15–2983; P<0.001) than in the CR group. In addition, nine patients in the NR group reached ESRD compared with two in the PR group (HR, 7.14; 95% CI, 2.61–19.48; P<0.001), whereas ESRD did not occur in the CR group (Supplemental Table 3). When we re-analyzed the data using an eGFR cutoff of <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 instead of serum creatinine ≤1.2 mg/dl, the results of these two analyses were similar (Supplemental Table 4). Because of concerns about lower eGFR in female patients for the same creatinine levels compared with male patients, we tested an interaction between sex and eGFR. However, there was no significant interaction between the two variables (data not shown).

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazard model for the primary endpoint in IgA nephropathy patients with nephrotic syndrome (n=100)

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Adjusteda | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Sex (male versus female) | 1.11 (0.49–2.54) | 0.79 | 1.94 (0.50–5.64) | 0.34 | 3.17 (0.76–13.13) | 0.12 |

| Age (per 1 yr) | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.56 | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) | 0.40 | 0.98 (0.95–1.02) | 0.42 |

| Diabetes mellitus (versus non-diabetes mellitus) | 1.10 (0.15–8.32) | 0.92 | 2.01 (0.18–22.66) | 0.57 | 1.03 (0.07–15.20) | 0.91 |

| Baseline 24-h proteinuria (per 1 g/d) | 2.53 (1.07–5.99) | 0.03 | 0.94 (0.75–1.18) | 0.59 | 1.28 (0.98–1.72) | 0.07 |

| Mean arterial pressure (per 1 mmHg) | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.22 | 1.02 (0.96–1.10) | 0.51 | 1.02 (0.95–1.10) | 0.62 |

| SCr ≤1.2 mg/dl (versus >1.2 mg/dl) | 3.01 (1.32–6.87) | 0.01 | 5.78 (1.57–21.30) | 0.01 | 4.03 (1.05–15.46) | 0.04 |

| Clinical responses | ||||||

| complete remission | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | — | ||

| partial remission | 7.24 (0.84–69.29) | 0.07 | 14.49 (1.14–183.76) | 0.04 | 10.57 (0.67–177.16) | 0.09 |

| no response or progression | 97.34 (12.22–775.31) | <0.001 | 215.97 (15.63–2983.60) | <0.001 | 369.48 (18.25–7495.96) | <0.001 |

| Haas classification | ||||||

| class I + II | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | — | — | — | |

| class III | 1.74 (0.38–7.95) | 0.48 | 0.95 (0.16–5.34) | 0.95 | — | — |

| class IV | 2.23 (0.6–8.27) | 0.23 | 0.35 (0.06–2.01) | 0.23 | — | — |

| class V | 8.97 (2.16–37.17) | 0.01 | 1.10 (0.22–5.36) | 0.91 | — | — |

| Oxford classification | ||||||

| M1 (versus M0) | 1.95 (0.71–5.33) | 0.26 | — | — | 1.65 (0.48–6.46) | 0.44 |

| E1 (versus E0) | 0.79 (0.33–1.94) | 0.62 | — | — | 0.52 (0.15–1.68) | 0.32 |

| S1 (versus S0) | 1.15 (0.50–2.60) | 0.71 | — | — | 4.19 (0.93–18.86) | 0.06 |

| T1+T2 (versus T0) | 8.6 (2.29–30.90) | 0.001 | — | — | 0.70 (0.09–5.56) | 0.69 |

All data are expressed as median (range). HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; SCr, serum creatinine; M, mesangial proliferation; E, endocapillary proliferation; S, segmental sclerosis; T, tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis; —, not applicable.

Adjusted for sex, age, diabetes mellitus, baseline 24-hour proteinuria, mean arterial pressure, SCr, and pathologic findings.

Interestingly, no patients with SR reached the primary or secondary endpoints (Supplemental Table 3). SR occurred mainly within 6 months after NS onset. The median times to SR and >50% reduction in proteinuria were 154 and 52 days, respectively. Only two patients (8.3%) in the SR group experienced relapse of NS, compared with 11 (45.8%) in the immunosuppressive agent group (P<0.001). Of the two relapsed patients in the SR group, one re-entered SR after 6 months without corticosteroids, whereas the other exhibited a spontaneous decrease in proteinuria shortly after the relapse with a UPCR of 1.49 g/g at the final visit.

Clinical Predictors of SR or CR in NS Patients with IgAN

We further investigated the factors associated with SR of NS in patients with IgAN. A >50% decrease in proteinuria within 3 months after NS onset (HR, 8.37; 95% CI, 3.12–22.40; P<0.001), serum creatinine ≤1.2 mg/dl (HR, 4.85; 95% CI, 1.21–19.39; P=0.02), and female sex (HR, 3.81; 95% CI, 1.39–10.45; P=0.009) were associated with a significantly increased likelihood of SR in multivariate Cox regression analysis adjusted for age, mean arterial pressure, and pathologic findings (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazard model for prediction of spontaneous remission of nephrotic syndrome in patients with IgA nephropathy (n=100)

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Adjusteda | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Sex (female versus male) | 1.37 (0.62–3.04) | 0.44 | 3.81 (1.39–10.45) | 0.009 | 3.45 (1.17–10.15) | 0.02 |

| Age (per 1 yr) | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) | 0.79 | 1.01 (0.97–1.02) | 0.69 | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 0.52 |

| Mean arterial pressure (per 1 mmHg) | 0.98 (0.95–1.02) | 0.38 | 0.99 (0.95–1.02) | 0.47 | 0.99 (0.96–1.04) | 0.88 |

| Baseline 24-h proteinuria (per 1 g/d) | 0.92 (0.78–1.09) | 0.32 | 1.10 (0.87–1.35) | 0.44 | 1.12 (0.92–1.37) | 0.27 |

| Proteinuria decrease >50% within 3 mo | 6.16 (2.72–13.96) | <0.001 | 8.37 (3.12–22.40) | <0.001 | 9.71 (3.51–26.87) | <0.001 |

| SCr ≤1.2 mg/dl (versus >1.2 mg/dl) | 3.50 (1.04–11.75) | 0.04 | 4.85 (1.21–19.39) | 0.02 | 4.20 (1.05–16.76) | 0.04 |

| Haas classification | ||||||

| class I + II | 1.22 (0.36–4.17) | 0.69 | 1.10 (0.24–4.66) | 0.92 | — | — |

| class III | 0.84 (0.24–2.97) | 0.74 | 0.76 (0.17–3.39) | 0.72 | — | — |

| class IV | 0.65 (0.19–2.23) | 0.42 | 1.10 (0.27–4.13) | 0.92 | — | — |

| class V | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | — | — | ||

| Oxford classification | ||||||

| M1 (versus M0) | 0.54 (0.24–1.22) | 0.14 | — | — | 1.98 (0.66–5.98) | 0.18 |

| E1 (versus E0) | 1.30 (0.56–2.97) | 0.53 | — | — | 0.76 (0.27–2.12) | 0.61 |

| S1 (versus S0) | 1.66 (0.72–3.78) | 0.23 | — | — | 1.11 (0.40–3.04) | 0.81 |

| T1+T2 (versus T0) | 0.44 (0.10–1.88) | 0.17 | — | — | 2.42 (0.44–12.38) | 0.26 |

All data are expressed as median (range). HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; SCr, serum creatinine; M, mesangial proliferation; E, endocapillary proliferation; S, segmental sclerosis; T, tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis; —, not applicable.

Adjusted for sex, age, mean arterial pressure, baseline 24-hour proteinuria, a >50% decrease in proteinuria within 3 months, SCr, and pathologic findings.

We also examined factors associated with all CR (achieved by immunosuppressive agents or conservative treatment only). In addition to a >50% decrease in proteinuria within 3 months, more favorable histologic findings by both Haas and Oxford classification were associated with CR (Supplemental Table 5).

Discussion

To date, NS has not been well characterized in patients with IgAN. Most previous studies involved only small numbers of patients with MCD-like features who had minimal histologic lesions and normal renal function (8,19). Accordingly, corticosteroids were commonly prescribed, with most patients responding well to this treatment. However, NS may occur in any subclass of IgAN and corticosteroids do not consistently result in complete resolution of heavy proteinuria (11,13,14,20). These findings suggest that MCD is not entirely responsible for the development of NS in patients with IgAN. In this study, we conducted an in-depth review of more than 1000 cases of IgAN from four tertiary medical centers in Korea, and recruited 100 patients who had NS features. To our knowledge, our study reports the largest sample of patients with this rare condition to date.

One major finding in this study was that the prognosis of NS in patients with IgAN was not superior to that of patients with classic IgAN. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution because most patients who reached the study endpoint were in the NR group. In fact, only two patients in the CR group reached the primary outcome without developing ESRD. Renal survival in this group was excellent, with a 7-year survival of 95.8% (Figure 2). In addition, we note that patients who attained PR also had favorable outcomes. In these patients, the risk reduction for the primary outcome was much greater than those in the NR group. The importance of PR has been suggested for various glomerulopathies (1,21,22). In particular, Reich et al. indicated that patients with IgAN who initially presented with proteinuria >3 g/d and achieved PR (<1 g/d) had similar outcomes to patients with persistent proteinuria of <1 g/d during follow-up and also had superior prognoses to patients who never achieved remission (1). However, that study included all patients with IgAN irrespective of kidney function, even those with serum creatinine concentrations up to 8.31 mg/dl. In addition, whether patients with NS were included is uncertain. Therefore, heavy proteinuria in some of the included patients was presumably because of advanced kidney disease from IgAN per se. In contrast, we included only patients who had typical features of NS with eGFR ≥30 ml/min per 1.73 m2. This unique subgroup of patients should be analyzed separately because few studies outline the therapeutic implications of this rare condition, although corticosteroids appeared to be favored with inconsistent results (9,11,13,20), Nevertheless, our findings are in line with those of previous studies suggesting the importance of remission, whether complete or partial, to improve renal outcomes.

Another valuable finding of our study was that SR was more common than expected, with 24% of NS patients experiencing SR. More than 20 years after the publication of two case reports of SR in NS with IgAN (23,24), we recently reported that 5 (20.8%) of 24 patients with IgAN presenting with NS entered SR shortly after NS onset (14). However, this was a single-center study with a limited number of patients. The results presented here were derived from a larger sample of patients, allowing comprehensive analyses to characterize these patients and to identify factors associated with SR. Our results support our earlier findings that SR was common, with many SR patients exhibiting spontaneous decreases in proteinuria within 1–3 months after NS onset. All patients with SR had excellent outcomes without progression.

Interestingly, in this study, SR occurred irrespective of IgAN subclass, which we had observed in our earlier study (14). For example, 11 patients who had a Haas classification of IV or V experienced SR. The pathologic findings in these patients did not correspond with the definition of MCD. Moreover, diffusely effaced foot processes, which are a typical feature of MCD, were observed in only 45.8% of patients. These findings suggest that MCD cannot explain all cases of IgAN with NS. As suggested previously, nephrotic range proteinuria in patients with IgAN might be caused by other forms of NS or accompanying GN (6,14).

Several shortcomings of this study should be discussed. First, no consensus exists regarding whether NS in IgAN is an MCD with incidental IgA deposition or a true IgAN. However, the results of several studies suggest that the former is more likely when biopsy findings show a class I lesion by the Haas classification, diffuse foot process effacement, and trace or approximately 1+ IgA deposition (10,25). This study included only four patients who met these criteria. Although they were excluded from the analyses, our results remained unaltered (data not shown). In addition, concomitant C3 deposition was found in 91 patients (91%) with NS (Supplemental Table 1). Because C3 deposition is commonly found in IgAN (26), together these findings favor a diagnosis of true IgAN for our study participants. Second, although most previous studies recommended corticosteroid therapy as used for MCD (27), our observational study had no preset indications for treating NS in patients with IgAN. Accordingly, treatment differed depending on individual physician preferences. Therefore, worse outcomes in patients with NR might be attributed to relatively shorter durations of corticosteroid therapy or early treatment discontinuation. Nevertheless, NR patients exhibited no signs of improvement despite receiving corticosteroids for at least 3 months. Considering the inconsistent results from several studies regarding steroid responsiveness in patients with IgAN complicated by NS (9,11,13,20), a more well designed, prospective, randomized, controlled study is required to address this unresolved issue. Third, as mentioned in our previous study, because most NS patients were treated with renin–angiotensin system (RAS) blockers, the identification of SR may be technically inaccurate. However, complete disappearance of heavy proteinuria is very unlikely to be achieved by RAS blocker treatment alone because RAS blockers decrease proteinuria by 30%–40% from baseline at best, with a varying extent of decrease (28,29). Fourth, the median observation period of this study was 45.2 months (range, 9.0–134.6). Therefore, we were unable to determine if patients in remission had favorable long-term outcomes. However, two patients who achieved CR after corticosteroid therapy developed a two-fold increase in serum creatinine levels at 7.7 and 9.0 years after the first remission. Given the very slow development of IgAN, a longer period of observation is required to validate our findings. Fifth, our results may not be extrapolated to other ethnic populations because a prior study suggested a geographical variability in long-term outcomes of IgAN (30). Finally, there were many covariates in some multivariate models. However, these are previously known to be strongly associated with outcomes, and thus were included in the models to confirm our findings.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that IgAN patients with NS had worse renal outcomes than did those without NS. At the very least, PR should be achieved to delay the progression of kidney disease, because patients who underwent remission had far better outcomes than patients who never achieved remission. These findings suggest that achieving remission, whether complete or partial, is of paramount importance in heavily proteinuric patients to improve renal survival, irrespective of glomerular disease type. In addition, SR of NS is common, particularly in patients with a spontaneous substantial decrease in proteinuria shortly after NS onset, and with preserved kidney function. Our novel findings may have therapeutic implications for the management of NS in patients with IgAN.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Yonsei University (Brain Korea 21) Project for Medical Sciences, a grant from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation funded by the Korean government (MOST) (R13-2002-054-04001-0), and a grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project of the Ministry for Health, Welfare, and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (A084001).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.04820511/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Reich HN, Troyanov S, Scholey JW, Cattran DC; Toronto Glomerulonephritis Registry: Remission of proteinuria improves prognosis in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 3177–3183, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donadio JV, Grande JP: IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med 347: 738–748, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radford MG, Jr, Donadio JV, Jr, Bergstralh EJ, Grande JP: Predicting renal outcome in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 199–207, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samuels JA, Strippoli GF, Craig JC, Schena FP, Molony DA: Immunosuppressive treatments for immunoglobulin A nephropathy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nephrology (Carlton) 9: 177–185, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delclaux C, Jacquot C, Callard P, Kleinknecht D: Acute reversible renal failure with macroscopic haematuria in IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 8: 195–199, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nachman PH, Jennette JC, Falk RJ: Primary glomerular disease. In: Brenner & Rector's The Kidney, 8th Ed., edited by Brenner BM, Philadelphia, Saunders Elsevier, 2008, pp 1024–1032 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donadio JV, Bergstralh EJ, Grande JP, Rademcher DM: Proteinuria patterns and their association with subsequent end-stage renal disease in IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 1197–1203, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai KN, Lai FM, Chan KW, Ho CP, Leung AC, Vallance-Owen J: An overlapping syndrome of IgA nephropathy and lipoid nephrosis. Am J Clin Pathol 86: 716–723, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinnassamy P, O’Regan S: Mesangial IgA deposits with steroid responsive nephrotic syndrome: Probable minimal lesion nephrosis. Am J Kidney Dis 5: 267–269, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi J, Jeong HJ, Lee HY, Kim PK, Lee JS, Han DS: Significance of mesangial IgA deposition in minimal change nephrotic syndrome: A study of 60 cases. Yonsei Med J 31: 258–263, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai KN, Lai FM, Ho CP, Chan KW: Corticosteroid therapy in IgA nephropathy with nephrotic syndrome: A long-term controlled trial. Clin Nephrol 26: 174–180, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai KN, Mac-Moune Lai F, Li PK, Chan KW, Au TC, Tong KL: The clinicopathological characteristics of IgA nephropathy in Hong Kong. Pathology 20: 15–19, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SM, Moon KC, Oh KH, Joo KW, Kim YS, Ahn C, Han JS, Kim S: Clinicopathologic characteristics of IgA nephropathy with steroid-responsive nephrotic syndrome. J Korean Med Sci 24[Suppl]: S44–S49, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han SH, Kang EW, Park JK, Kie JH, Han DS, Kang SW: Spontaneous remission of nephrotic syndrome in patients with IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 1570–1575, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.: K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39[Suppl 1]: S1–S266, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haas M: Histologic subclassification of IgA nephropathy: A clinicopathologic study of 244 cases. Am J Kidney Dis 29: 829–842, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cattran DC, Coppo R, Cook HT, Feehally J, Roberts IS, Troyanov S, Alpers CE, Amore A, Barratt J, Berthoux F, Bonsib S, Bruijn JA, D’Agati V, D’Amico G, Emancipator S, Emma F, Ferrario F, Fervenza FC, Florquin S, Fogo A, Geddes CC, Groene HJ, Haas M, Herzenberg AM, Hill PA, Hogg RJ, Hsu SI, Jennette JC, Joh K, Julian BA, Kawamura T, Lai FM, Leung CB, Li LS, Li PK, Liu ZH, Mackinnon B, Mezzano S, Schena FP, Tomino Y, Walker PD, Wang H, Weening JJ, Yoshikawa N, Zhang H; Working Group of the International IgA Nephropathy Network and the Renal Pathology Society: The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: Rationale, clinicopathological correlations, and classification. Kidney Int 76: 534–545, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radhakrishnan J, Appel AS, Valeri A, Appel GB: The nephrotic syndrome, lipids, and risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Kidney Dis 22: 135–142, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng IK, Chan KW, Chan MK: Mesangial IgA nephropathy with steroid-responsive nephrotic syndrome: Disappearance of mesangial IgA deposits following steroid-induced remission. Am J Kidney Dis 14: 361–364, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mustonen J, Pasternack A, Rantala I: The nephrotic syndrome in IgA glomerulonephritis: Response to corticosteroid therapy. Clin Nephrol 20: 172–176, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen YE, Korbet SM, Katz RS, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ; Collaborative Study Group: Value of a complete or partial remission in severe lupus nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 46–53, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Troyanov S, Wall CA, Miller JA, Scholey JW, Cattran DC; Toronto Glomerulonephritis Registry Group: Focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis: Definition and relevance of a partial remission. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1061–1068, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu G, Katz A, Cardella C, Oreopoulos DG: Spontaneous remission of nephrotic syndrome in IgA glomerular disease. Am J Kidney Dis 6: 96–99, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogg RJ, Savino DA: Spontaneous remission of nephrotic syndrome in a patient with IgA nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol 4: 36–38, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeong HJ, Jung SH, Choi IJ: Electron microscopic study of the cases of minimal change nephrotic syndrome with mesangial IgA deposition. Yonsei Med J 33: 351–356, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jennette JC, Heptinstall RH: Heptinstall's Pathology of the Kidney, Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strippoli GF, Manno C, Schena FP: An “evidence-based” survey of therapeutic options for IgA nephropathy: Assessment and criticism. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 1129–1139, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakris G, Burgess E, Weir M, Davidai G, Koval S; AMADEO Study Investigators: Telmisartan is more effective than losartan in reducing proteinuria in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 74: 364–369, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S; RENAAL Study Investigators: Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 345: 861–869, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geddes CC, Rauta V, Gronhagen-Riska C, Bartosik LP, Jardine AG, Ibels LS, Pei Y, Cattran DC: A tricontinental view of IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 1541–1548, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.