Abstract

The vitamin D3 catabolizing enzyme, CYP24, is frequently over-expressed in tumors, where it may support proliferation by eliminating the growth suppressive effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3). However, the impact of CYP24 expression in tumors or consequence of CYP24 inhibition on tumor levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 in vivo has not been studied due to the lack of a suitable quantitative method. To address this need, an LC-MS/MS assay that permits absolute quantitation of 1,25(OH)2D3 in plasma and tumor was developed. We applied this assay to the H292 lung tumor xenograft model: H292 cells eliminate 1,25(OH)2D3 by a CYP24-dependent process in vitro, and 1,25(OH)2D3 rapidly induces CYP24 expression in H292 cells in vivo. In tumor-bearing mice, plasma and tumor concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 reached a maximum of 21.6 ng/mL and 1.70 ng/mL respectively, following intraperitoneal dosing (20 µg/kg 1,25(OH)2D3). When co-administered with the CYP24 selective inhibitor CTA091 (250 µg/kg), 1,25(OH)2D3 plasma levels increased 1.6-fold, and tumor levels increased 2.6-fold. The tumor/plasma ratio of 1,25(OH)2D3 AUC was increased 1.7-fold by CTA091, suggesting that the inhibitor increased the tumor concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 independent of its effects on plasma disposition. Compartmental modeling of 1,25(OH)2D3 concentration versus time data confirmed that: 1,25(OH)2D3 was eliminated from plasma and tumor; CTA091 reduced the elimination from both compartments; and that the effect of CTA091 on tumor exposure was greater than its effect on plasma. These results provide evidence that CYP24-expressing lung tumors eliminate 1,25(OH)2D3 by a CYP24-dependent process in vivo and that CTA091 administration represents a feasible approach to increase tumor exposure to 1,25(OH)2D3.

Keywords: lung cancer; CTA091; CYP24; 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3; pharmacokinetics

Introduction

The active metabolite of vitamin D3, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3)1, exerts anti-proliferative activity by binding to the vitamin D receptor (VDR) and thereby regulating gene expression [1]. Recent studies suggest that 1,25(OH)2D3 signaling inhibits the growth of established lung cancers. For example, 1,25(OH)2D3 significantly inhibits the growth of some human lung cancer cell lines in vitro [2–4]. In other studies, serum levels of the 1,25(OH)2D3 precursor 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3) were positively associated with survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients [5], and high nuclear VDR levels in primary lung tumors were associated with significantly better overall survival [6]. Factors that reduce local 1,25(OH)2D3 levels or signaling are predicted to support lung tumor growth and negatively impact patient outcome.

The mitochondrial P450 enzyme, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-24-hydroxylase (CYP24) is the predominant enzyme responsible for the catabolic inactivation of 1,25(OH)2D3 [7]. CYP24 is frequently over-expressed in primary human lung tumors, where it may contribute to neoplastic growth by increasing the local elimination of 1,25(OH)2D3 [8–10]. A pro-tumorigenic role for CYP24 is supported both by the recent discovery that CYP24 mRNA expression is an independent predictor of poor survival in patients with lung adenocarcinoma [4], and by our prior finding that selective pharmacologic inhibition of CYP24 blocks 1,25(OH)2D3 catabolism by lung cancer cells and increases its potency for growth inhibition in vitro [3]. The impact of tumor CYP24 expression on the local elimination of 1,25(OH)2D3 in vivo has not yet been determined.

Typically, CYP24 transcription is increased by 1,25(OH)2D3 in target tissues including the kidney, colon, intestine, and bone [11–13]. Physiologically, CYP24 may be induced by 1,25(OH)2D3 to attenuate its action and prevent accumulation of toxic concentrations which would result in hypercalcemia. CYP24 induction is initiated when 1,25(OH)2D3 binds to and activates the VDR. The activated receptor binds to vitamin D response elements (VDREs) located both within the CYP24 promoter and downstream of the CYP24 gene, resulting in robust transcriptional enhancement [14–16]. In mice lacking either the VDR gene or the CYP24 gene, elevated blood levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 were observed suggesting that VDR mediated induction of CYP24 is required for efficient 1,25(OH)2D3 normalization [17–18].

Selective CYP24 inhibitors have been developed [19–22]. We hypothesize that these inhibitors may improve the efficacy of 1,25(OH)2D3 for lung cancer treatment by increasing systemic exposure to 1,25(OH)2D3 and preventing the local inactivation of 1,25(OH)2D3 by lung tumors. It has not previously been possible to study the effects of CYP24 inhibition on 1,25(OH)2D3 plasma and tumor pharmacokinetics (PK) due to the lack of a suitable assay for quantifying the active metabolite in a tumor matrix. To address this need, we developed the liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) assay reported in this paper. We used this assay to characterize 1,25(OH)2D3 PK in the absence and presence of the CYP24 selective inhibitor, CTA091. CTA091 is a 24-sulfoximine analogue of 1,25(OH)2D3 which binds to the substrate binding pocket of CYP24 and has previously been shown to increase plasma 1,25(OH)2D3 exposure in rats [23–24].

In the H292 human lung tumor xenograft model, CTA091 significantly increased both the plasma and tumor Cmax and AUC of co-administered 1,25(OH)2D3. However, the increase in tumor exposure to 1,25(OH)2D3 was not simply explained by a CTA091-mediated increase in plasma PK. Rather, our data suggest that lung tumors eliminate 1,25(OH)2D3 in vivo, and that this local elimination may be preferentially inhibited via the use of CTA091. These findings suggest that CYP24 inhibitors may be useful in overcoming the deleterious effects of aberrant CYP24 expression in human tumors. The assay we describe should be useful in addressing other clinically relevant questions about 1,25(OH)2D3 pharmacokinetics.

Experimental

Chemicals and Reagents

1,25(OH)2D3 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). [D6]-1,25(OH)2D3 (internal standard) was purchased from Medical Isotopes, Inc. (Pelham, NH). The CYP24 inhibitor CTA091 was generously provided by Cytochroma, Inc. (Markham, Ontario, Canada). For in vitro studies, CTA091 was used at a final concentration of 50 nM. At this concentration, CTA091 consistently and maximally inhibits 1,25(OH)2D3 catabolism and significantly increases 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated transcription (Zhang et al., manuscript under review). Methanol and water (HPLC grade) were purchased from Burdick and Jackson (Fombell, PA, USA). Methylene chloride, ammonium acetate and isopropanol (all HPLC grade) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, NJ, USA). Nitrogen for evaporation of samples was purchased from Valley National Gases, Inc. (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Nitrogen for mass spectrometrical applications was purified with a Parker Balston Nitrogen Generator (Parker Balston, Haverhill, MA, USA).

Cells

H292 human lung cancer cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). H292 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone Laboratories, Inc., Logan, UT), 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The cell line was authenticated by RADIL (St. Louis, MO) and determined to be mycoplasma-free using the Venor GeM mycoplasma detection kit (Sigma Aldrich).

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

RNA was isolated from H292 cells or tumor sections using the RNAgents system (Promega, Madison, WI) according to manufacturer’s directions. The purified RNA was dissolved in nuclease-free water and quantitated by spectrophotometry at 260 nm. The integrity of each RNA preparation was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. One µg of RNA was reverse-transcribed using random hexamer primers and MMLV reverse transcriptase for 1 h at 42 °C, as per instructions in the Advantage RT-for-PCR kit (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA). The resulting cDNAs were diluted to a final volume of 100 µL in nuclease-free water. For qPCR, 2 µL of each cDNA were diluted in 1× Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Branchburg, New Jersey) in a final volume of 30 µL with either a CYP24 primer/probe set (200 nM primer and 200 nM probe) or a β-glucuronidase (GUS) primer/probe set (100 nM primer and 200 nM probe). The sequences of the CYP24 primers and probe were as follows: Forward primer 5’-CAT TTG GCT CTT TGT TGG ATT G; Reverse primer 5’-AGC ATC TCA ACA GGC TCA TTG TC; Probe 5’-/56-FAM-CCG CAA ATA CGA CAT CCA GGC CA-TAMRA. The GUS primer and probe sequences were from Herrera et al [25]. The qPCR reactions were run on an ABI 7700 sequence detection system (initial incubation at 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min) and the resulting data analyzed using Sequence Detection System software. Samples were assigned a Ct value for each gene (the cycle number at which the logarithmic PCR plots cross a fixed threshold). A CYP24 gene expression value (ΔCt) was calculated using the equation: ΔCt= [(Ct CYP24) – (Ct GUS)]. Linear mRNA expression values were obtained using the equation: mRNA expression = 2−ΔCt.

Tumor Xenografts

In vivo pharmacokinetic studies were conducted in 6–8 week old female nu/nu mice (Charles River Laboratories). Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions according to the guidelines of the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and studies were carried out under an approved institutional animal care and use protocol. Animals were housed in microisolator cages and provided food (Purina IsoPro Rodent 3000) and water ad libitum. Mice were fed the IsoPro diet upon their arrival and maintained on the same diet throughout the experiment. To establish xenografts, H292 cells in logarithmic growth (2.5×107 cells/mL) were mixed 1:1 with Matrigel (BD Biosciences). Two hundred µL of the suspension was injected subcutaneously into the left rear flank of each mouse. Once tumors developed, mice were stratified based on tumor volume to receive either 1,25(OH)2D3 alone (20 µg/kg ip) or 1,25(OH)2D3 (20 µg/kg ip) plus CTA091 (250 µg/kg ip). 1,25(OH)2D3 and CTA091 were dissolved in absolute ethanol and diluted in sterile saline for injection. For all groups, the final injection volume was fixed at 0.1 mL, and the final ethanol concentration of the treatment stock was 12.5%. Groups of 2–7 animals were taken at pre-specified time points for pharmacokinetic analyses. Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, and blood was collected via cardiac puncture using heparinized syringes. Blood samples were stored on ice until all the samples for a given time point had been collected. Plasma was then prepared by centrifugation of the blood sample at 4 °C for 4 min, 13,000 × g. Tumors were excised and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Plasma and tumor were stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Preparation of 1,25(OH)2D3 Standards

Stock solutions of 1,25(OH)2D3 standards were prepared in methanol and stored at −80°C. Standard curves were prepared by diluting the stock solutions in plasma or H292 lung tumor homogenate (both from tumor-bearing, untreated female nu/nu mice). Tumors were homogenized in PBS (1:3, g/v) prior to use. 1,25(OH)2D3 stocks were diluted into the appropriate matrix to achieve final concentrations ranging from 0.05 to 3 ng/mL (for tumor homogenate) or 0.1 to 100 ng/mL (for plasma).

Sample preparation

Sample preparation was performed on ice and in amber colored consumables when possible. To 200 µL of plasma or tumor homogenate were added 10 µL of internal standard (20 ng/mL of [D6]-1,25(OH)2D3 in methanol/water, 50:50 (v/v)), and 1 mL of methylene chloride. The mixture was vortexed for 1 min. The vortexed sample was centrifuged for 6 min at 14,000 × g, after which the bottom layer was aspirated and evaporated to dryness under nitrogen at 37°C. After reconstitution of the dried residue in 500 µL of methylene chloride, the sample was subjected to solid phase extraction. An NH2 Bond Elut Solid Phase Cartridge (200 mg, 3 mL, Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA) was conditioned with 2 × 2 mL of methanol, and 2 mL of methylene chloride. The reconstituted sample was loaded and then washed with 1 mL of methylene chloride and 1 mL of methylene chloride/isopropanol (98:2, v/v). The sample was eluted with 2 mL of methanol, evaporated to dryness under nitrogen at 37 °C, and reconstituted in 100 µL of mobile phase. The reconstituted sample was transferred to amber autosampler vials, and 50 µL was injected into the LC-MS/MS system.

Chromatography

The LC-MS/MS system consisted of an Agilent 1200 SL thermostated autosampler, binary pump with gradient. The liquid chromatography was performed with a gradient mobile phase consisting of A: methanol/2 mM ammonium acetate and B: 2 mM ammonium acetate. The mobile phase was pumped at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min and separation was achieved using a Phenomenex (Torrance, CA) Synergi Hydro-RP column (4 µm, 100 × 2 mm) column. The gradient mobile phase was as follows: at time zero, solvent A was 80%, increased linearly to 99% in 8 min, and kept constant between 8 and 13 min. From 13 to 14 min, the percentage of solvent A was decreased linearly to 80%, while the flow rate was increased to 0.4 mL/min. This was maintained from 14 to 19.5 min, after which the flow rate was decreased to 0.2 mL/min between 19.5 and 20 min. The first 4 min of the column effluent were diverted to waste and the total run time was 20 min, with 1,25(OH)2D3 eluting at approximately 12.5 min.

Mass spectrometric detection

Mass spectrometric detection was carried out using an MDS SCIEX 4000Q hybrid linear ion trap tandem mass spectrometer (MDS SCIEX, Concord, ON), with electrospray ionization operated in the positive mode, multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. The settings of the mass spectrometer were as follows: curtain gas 20, IS voltage 5500 V, probe temperature 400 °C, GS1 40, GS2 30, declustering potential 50 V, collision energy 12 V. Quadrupoles were set to unit resolution and dwell time of 0.15 s. The MRM m/z transitions monitored for 1,25(OH)2D3 and [D6]-1,25(OH)2D3 were 434.5 to 399.5, and 440.5 to 405.4, respectively. The HPLC system and mass spectrometer were controlled by Analyst software (version 1.4.2), and data were collected with the same software. The analyte-to-internal standard ratio was calculated for each standard by dividing the area of each analyte peak by the area of the respective internal standard peak for that sample. Standard curves of the analytes were constructed by plotting the analyte-to-internal standard ratio versus the known concentration of analyte in each sample. Standard curves were fit by linear regression with weighting by 1/y2, followed by back calculation of concentrations.

Pharmacokinetic analysis and statistical interpretation

1,25(OH)2D3 concentration versus time data in plasma and tumor (averages per time point) were analyzed non-compartmentally using PK Solutions 2.0 (Summit Research Services, Montrose, CO; www.summitPK.com). The area under the plasma concentration versus time curve (AUC) was calculated with the linear trapezoidal rule for the period of observed data (AUC0–8h), and the terminal elimination rate (ke) was derived from the last, linear part of the data, followed by calculation of the half-life from LN(2)/ke. Apparent clearance (Cl/F) was calculated as Dose/AUC, and apparent volume of distribution (Vd/F) was calculated as (Cl/F)/ke.

Data were also analyzed compartmentally with the ADAPT 5 software for pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic systems analysis [26]. The maximum likelihood option in ADAPT 5 was used for all estimations (informed with the intercept and slope of the standard deviation versus concentration relationship obtained from the respective calibration curves) and model selection was based on Akaike’s Information Criterion [27].

The effect of CTA091 on the elimination rates of 1,25(OH)2D3 in plasma and in tumor was assessed by calculating the 95% confidence interval of these effects. Any effect characterized by a factor was considered significant if the 95% confidence interval did not include 1. Any effect characterized by a rate constant was considered significant if the 95% confidence interval did not include 0.

Results

1,25(OH)2D3 induces CYP24 expression in H292 human lung cancer cells in vitro and in vivo

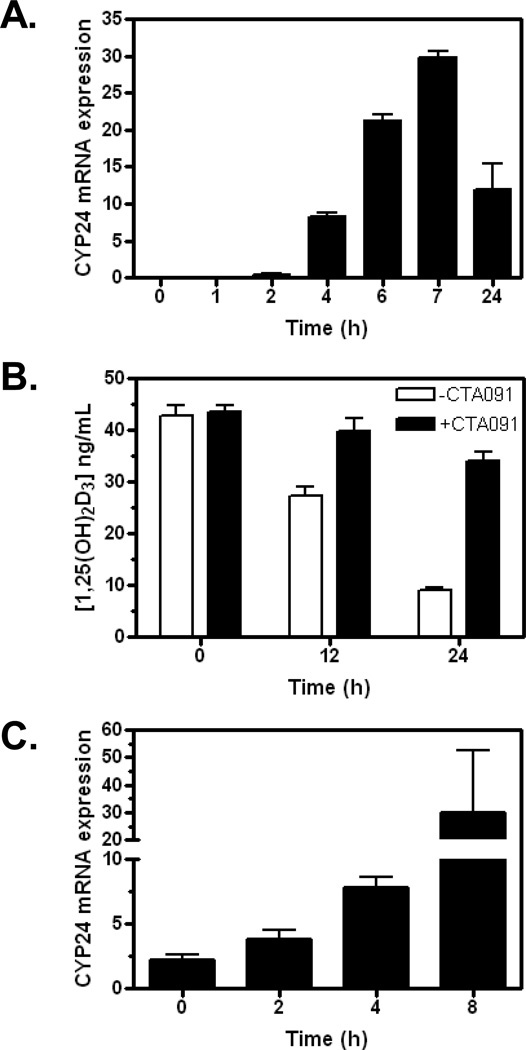

To study the effect of CYP24 on tumor elimination of 1,25(OH)2D3 in vivo, we selected the H292 human lung tumor xenograft as our model system. When treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 in vitro, H292 cells are induced to express CYP24 (Fig. 1A). CYP24 induction is associated with the time-dependent loss of 1,25(OH)2D3 from the culture system: only 20% of the initial dose remains 24 h post treatment (Fig. 1B). When H292 cells are exposed to 1,25(OH)2D3 in the presence of the CYP24-selective inhibitor CTA091, >80% of the starting concentration of 1,25(OH)2D3 remains after 24 h (Fig.1B). Although CTA091 alone has no effect on CYP24 gene expression, it increases by approximately 4-fold the transcriptional induction of CYP24 by 1,25(OH)2D3 (data not shown). Cumulatively, these data support the conclusion that CTA091 effectively suppresses CYP24-mediated catabolism of 1,25(OH)2D3 in H292 cells in vitro.

Figure 1.

H292 cells express CYP24 in vitro and in vivo. (A) H292 cells were treated with 1 nM 1,25(OH)2D3. At the times indicated, cells were harvested and RNA was prepared. CYP24 mRNA expression was determined by QPCR, as detailed in methods. Results are the average of two separate determinations. (B) H292 cells were exposed to 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 in the absence (white bars) or presence (black bars) of CTA091 (50 nM). At various times, tissue culture homogenates were prepared and 1,25(OH)2D3 concentrations determined by LC-MS/MS. Values represent the mean +/− SD for triplicate determinations. (C) Mice bearing H292 xenografts were treated with a single dose of 1,25(OH)2D3. At various times, tumors were harvested for determination of CYP24 mRNA levels by QPCR.

To determine whether 1,25(OH)2D3 also increases CYP24 expression in H292 cells in vivo (where it may contribute to tumor elimination of 1,25(OH)2D3), we treated mice bearing established H292 xenografts with a single dose of 1,25(OH)2D3. At various times thereafter, tumors were harvested and CYP24 mRNA expression was assessed by qPCR. CYP24 was expressed at low, but detectable levels immediately after 1,25(OH)2D3 administration (Fig. 1C). CYP24 mRNA levels were increased approximately 4-fold at 4 h post-treatment and nearly 15-fold after 8 h.

Development of an LC-MS/MS method for simultaneously quantitating 1,25(OH)2D3 in plasma and tumor tissue

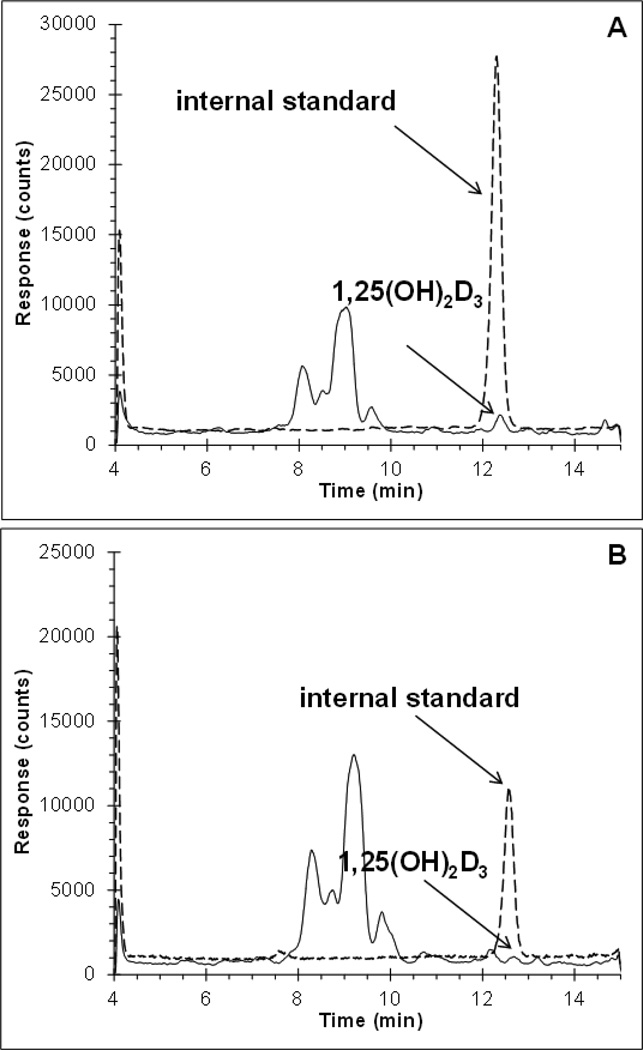

We developed an LC-MS/MS method that would allow for the absolute quantitation of 1,25(OH)2D3 in plasma and tumor tissue (see Fig. 2 and details in Methods). Murine plasma obtained from a commercial source displayed high endogenous concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 and was not suitable as the matrix for a 1,25(OH)2D3 standard curve. Instead, standard curves were generated in plasma and tumor tissue homogenates that had been prepared from untreated tumor-bearing mice that were strain, age, and sex-matched to our experimental mice. The plasma and tumor homogenate assays were linear between 0.1–100 ng/mL 1,25(OH)2D3 and 0.05–3 ng/mL 1,25(OH)2D3, respectively. Assay performance was assessed in triplicate using samples that contained 1,25(OH)2D3 at concentrations which spanned the dynamic range in each matrix (Table 1). The assay performed well in both matrices with accuracies between 87.3 and 110.7% and precisions within 2.9%. Extraction from each matrix was assessed by spiking 1 ng/mL 1,25(OH)2D3 directly into plasma or tumor homogenate from untreated mice. Extraction from plasma was nearly complete at 92%, whereas extraction from tumor homogenate was much lower at 11.0%. CTA091 did not interfere with the detection of 1,25(OH)2D3 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Chromatograms of 1,25(OH)2D3 (eluting at 12.5 min) at the lower limit of quantitation of (A) mouse plasma at 0.1 ng/mL, and (B) tumor homogenate at 0.05 ng/mL (1,25(OH)2D3, continuous line; internal standard, dashed line with an offset of +500).

Table 1.

Assay performance parameters at representative points along the dynamic range.

| [1,25(OH)2D3] (ng/mL) | Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | |||

| 0.1 | 95.0 | 2.5 | - |

| 1.0 | 110.7 | 1.9 | 92.2 (11.4) |

| 10 | 97.4 | 0.4 | - |

| 100 | 87.3 | 2.1 | - |

| Tumor homogenate | |||

| 0.1 | 110.7 | 2.9 | - |

| 0.3 | 105.0 | 2.6 | - |

| 1.0 | 89.6 | 0.8 | 11.0 (16.1) |

| 3.0 | 96.3 | 1.2 | - |

Assay performance was assessed in triplicate using samples that contained the indicated concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3. Precision was calculated as the relative standard deviation. Accuracy was calculated as the back-calculated concentration relative to the nominal concentration. Extraction recovery was assessed at 1 ng/mL 1,25(OH)2D3 and was calculated as the relative response of an extracted sample versus the response of a standard in mobile phase.

CYP24 contributes to the local elimination of 1,25(OH)2D3 by lung tumors

To establish the effect of tumor CYP24 expression on the elimination of 1,25(OH)2D3 in vivo, mice bearing H292 subcutaneous xenografts were administered, via the intraperitoneal (i.p.) route, 1,25(OH)2D3 alone (20 µg/kg) or 1,25(OH)2D3 plus CTA091 (250 µg/kg). Twenty µg/kg 1,25(OH)2D3 was selected for use in these studies because it is a dose at which the plasma PK of 1,25(OH)2D3 were previously characterized in a murine model using a different quantitative method [28]. The CTA091 dose was selected based on recommendations from the manufacturer and was expected to be biologically active given that a similar dose increased endogenous 1,25(OH)2D3 levels and decreased serum PTH levels in rats [24]. In pilot studies, 1,25(OH)2D3 and CTA091 could be co-administered at these doses without toxicity, and 1,25(OH)2D3 concentrations in the linear range for detection in both plasma and tumor tissues were obtained (data not shown).

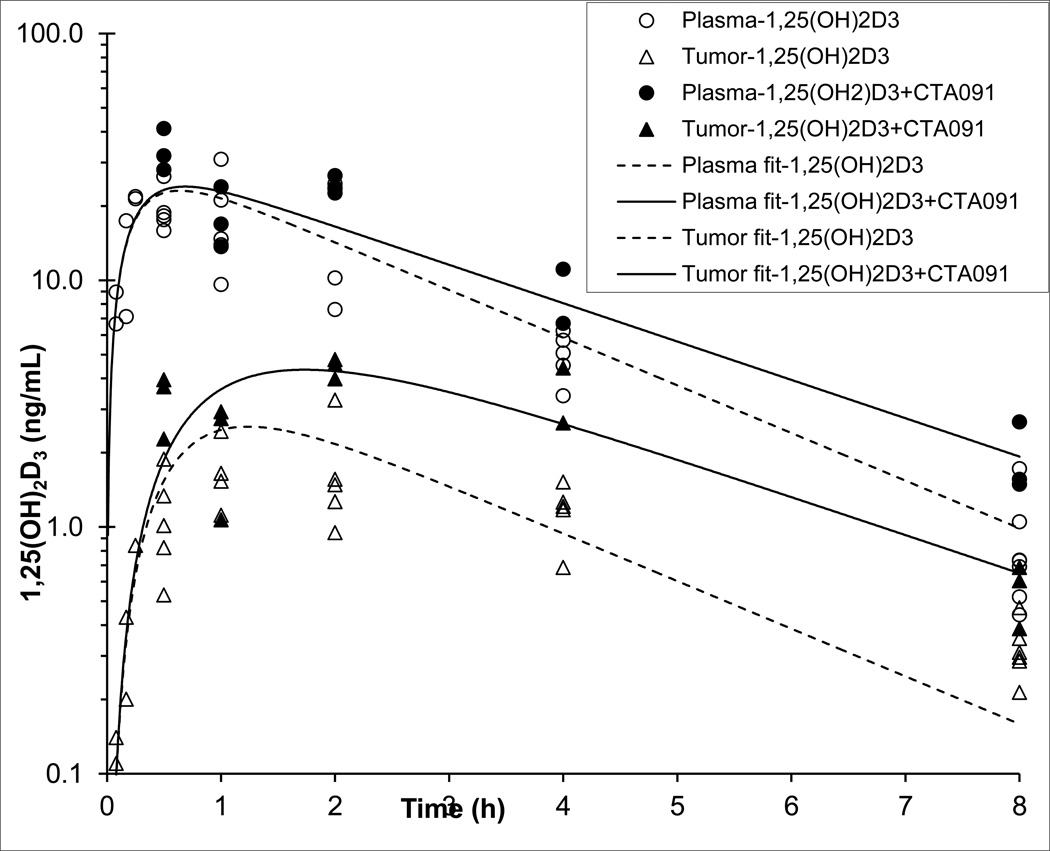

At various times post-treatment, blood and tumor tissue were collected for the determination of 1,25(OH)2D3 by LC-MS/MS. The plasma pharmacokinetic profiles of 1,25(OH)2D3 showed rapid absorption from the peritoneal cavity with a Tmax of 0.25 h, followed by a first order elimination phase (Figure 3). Non-compartmental analysis indicated that the addition of the CYP24 inhibitor CTA091 increased the 1,25(OH)2D3 plasma exposure approximately 1.5-fold, and the terminal half-life approximately 1.2-fold (Table 2). The tumor 1,25(OH)2D3 concentration versus time profile was in accordance with that of a peripheral compartment, with Tmax, at 2 h, lagging behind the plasma Tmax of 0.25–0.5 h. Tumor concentrations were markedly lower than plasma concentrations, with an AUC ratio of tumor versus plasma of 13% and 22%, for 1,25(OH)2D3 alone and with CTA091, respectively. The presence of CTA091 increased the tumor versus plasma ratio of the 1,25(OH)2D3 AUC by a factor of approximately 1.8.

Figure 3.

Concentration versus time data and model fits of 1,25(OH)2D3 in plasma (circles) and tumor (triangles) after i.p. administration to tumor-bearing nu/nu mice of 20 µg/kg 1,25(OH)2D3 either alone (open symbols, dashed lines) or in combination with 250 µg/kg of the CYP24 inhibitor, CTA091 (solid symbols, solid lines).

Table 2.

Results of the non-compartmental analysis of plasma and tumor 1,25(OH)2D3 concentration versus time data.

| Parameter | Unit | 1,25(OH)2D3 | 1,25(OH)2D3 + CTA091 | +/− CTA091 Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | ||||

| AUC0–8h | ng/mL•h | 67.4 | 97.3 | 1.4 |

| AUC0-inf | ng/mL•h | 69.1 | 102 | 1.5 |

| Cmax | ng/mL | 21.6 | 33.7 | 1.6 |

| Tmax | h | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2 |

| Vd/F | L/kg | 0.592 | 0.469 | 0.79 |

| Kel | h−1 | 0.489 | 0.419 | 0.86 |

| t1/2 | h | 1.42 | 1.66 | 1.2 |

| Cl/F | L/h/kg | 0.289 | 0.196 | 0.68 |

| Tumor | ||||

| AUC0–8h | ng/g•h | 8.39 | 21.7 | 2.6 |

| AUC0-inf | ng/g•h | 9.18 | 22.9 | 2.5 |

| Cmax | ng/g | 1.70 | 4.43 | 2.6 |

| Tmax | h | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| kel | h−1 | 0.355 | 0.460 | 1.3 |

| t1/2 | h | 1.95 | 1.51 | 0.77 |

| Tumor/plasma | ||||

| AUC0–h | - | 0.125 | 0.22 | 1.8 |

| Cmax | - | 0.079 | 0.13 | 1.7 |

Concentration versus time data were obtained after i.p. administration of 20 µg/kg 1,25(OH)2D3 either alone or in combination with 250 µg/kg of CTA091 to mice bearing subcutaneous H292 lung tumors. AUC0–8h, area under the concentration versus time curve from 0 to 8 h; AUC0-inf, area under the concentration versus time curve from 0 to infinity; Cmax, maximum concentration; Tmax, time of Cmax; Vd/F, apparent volume of distribution; kel, elimination rate constant; t½, half-life; Cl/F, apparent clearance.

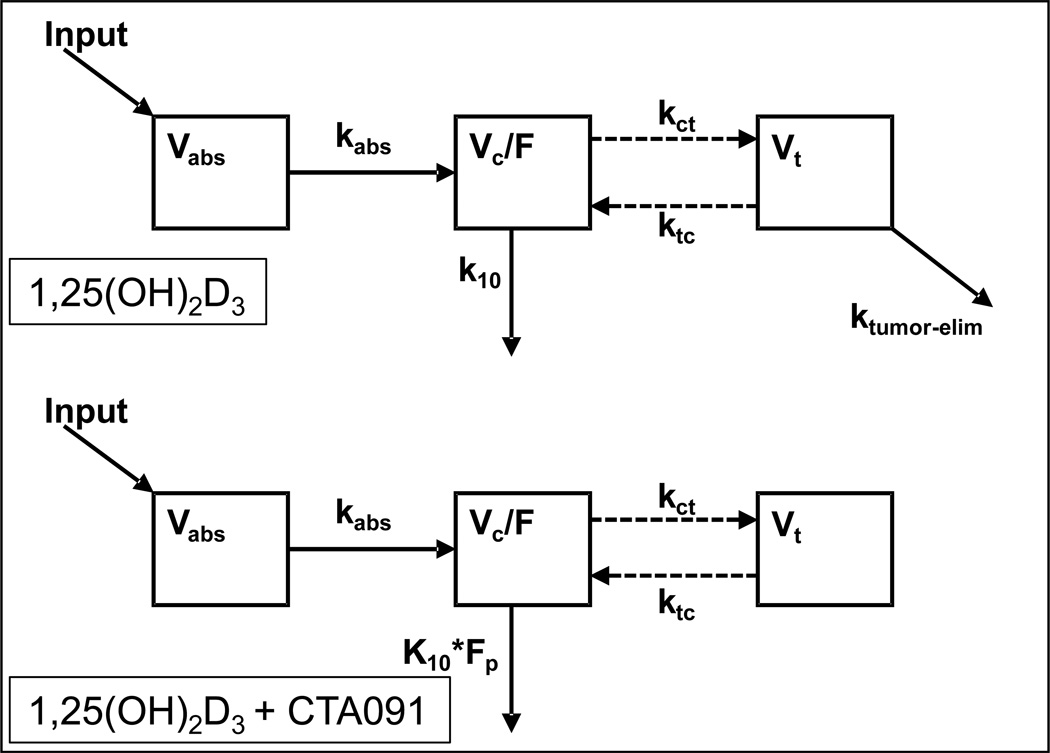

The plasma elimination rate constant (kl0) for 1,25(OH)2D3 and the apparent volume distribution (Vc/F) were estimated by compartmental analysis by fitting a one-compartment, open, linear model to the plasma 1,25(OH)2D3 concentration versus time data (see model, Fig. 4). The half-life (t1/2) of decline of 1,25(OH)2D3 was calculated as 0.693/k10. Apparent clearance (Cl/F) was calculated as (Vc/F)•(k10). Next, an uncoupled tumor compartment was added to the model to be fit to the tumor concentration data. The uncoupled compartment approach allowed the concentration in the central compartment to drive entry to the tumor compartment and tumor concentration to drive loss from the tumor compartment, without having the amount of 1,25(OH)2D3 in the central compartment being affected by these processes. The tumor volume was arbitrarily fixed at 1 L/kg. Next, the plasma and tumor 1,25(OH)2D3 concentration data after co-administration of 1,25(OH)2D3 and CTA091 were added to the dataset with the hypothesis that CTA091 could separately impact elimination of 1,25(OH)2D3 from the central compartment (expressed as the factor Fp), and to inhibit elimination of 1,25(OH)2D3 from the tumor (expressed as ktumor-elim). The model fit the data well (Table 3), and the modest R2 values merely reflect the variability in 1,25(OH)2D3 concentration values among mice sampled at identical time points. Plasma pharmacokinetic parameters derived by non-compartmental and compartmental means were comparable. The factor by which the co-administration of CTA091 changed the elimination rate from the central compartment (Fp) was 0.805, and its 95% confidence interval did not include 1, thereby reaching significance. The elimination of 1,25(OH)2D3 from the tumor which could be inhibited by co-administration of CTA091, independently from its effect on plasma exposure, was characterized by a rate constant ktumor-elim of 1.05 h−1, with a 95% confidence interval that did not include 0, thereby also reaching significance.

Figure 4.

Model structure used to estimate pharmacokinetic parameters of 1,25(OH)2D3 in plasma and tumors. Note how the co-administration of CTA091 is hypothesized to both impact elimination of 1,25(OH)2D3 from the central compartment (Fp), and to inhibit elimination of 1,25(OH)2D3 from the tumor (ktumor-elim).

Table 3.

Results of the compartmental analysis of plasma and tumor 1,25(OH)2D3 concentration versus time data

| 1,25(OH)2D3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Unit | Estimate (%SE) | 95%-CI |

| Plasma | |||

| ka | h−1 | 3.82 (19) | 2.36–5.28 |

| Vc/F | L/kg | 0.653 (8.4) | 0.543–0.763 |

| k10 | h−1 | 0.445 (5.3) | 0.398–0.491 |

| Fp | - | 0.805 (7.1) | 0.691–0.919 |

| Cl/F_1,25(OH)2D3 | L/h/kg | 0.291 (6.1) | 0.255–0.326 |

| Cl/F_1,25(OH)2D3+CTA091 | L/h/kg | 0.234 (7.7) | 0.198–0.270 |

| t½_1,25(OH)2D3 | h | 1.56 (5.3) | 1.40–1.72 |

| t½_1,25(OH)2D3+CTA091 | h | 1.94 (7.6) | 1.65–2.23 |

| R2_1,25(OH)2D3 | - | 0.695 | |

| R2_1,25(OH)2D3+CTA091 | - | 0.702 | |

| Tumor | |||

| Vt | L/kg | 1 (not estimated) | - |

| kct | h−1 | 0.454 (18) | 0.287–0.620 |

| ktc | h−1 | 1.24 (22) | 0.687–1.79 |

| ktumor-elim | h−1 | 1.04 (32) | 0.371–1.72 |

| t½_tumor-elim | h | 0.661 (32) | 0.236–1.09 |

| R2_1,25(OH)2D3 | - | 0.569 | |

| R2_1,25(OH)2D3+CTA091 | - | 0.447 | |

| AIC | - | 332.5 | |

Data were obtained after i.p. administration of 20 µg/kg 1,25(OH)2D3 either alone or in combination with 250 µg/kg of the CYP24 inhibitor CTA091 to mice bearing subcutaneous H292 lung tumors. Ka, absorption rate constant; Vc/F, apparent central volume of distribution; K10, 1,25(OH)2D3 elimination rate constant from the central compartment; Fp, factor by which CTA091 changes the elimination of 1,25(OH)2D3 from the central compartment; Cl/F, apparent clearance; t½, half-life; R2, correlation coefficient; Vt, tumor volume; kct, 1,25(OH)2D3 transfer rate constant from the central to the tumor compartment; ktc, 1,25(OH)2D3 transfer rate constant from the tumor to the central compartment; ktumor-elim, 1,25(OH)2D3 elimination rate constant from the tumor compartment that is inhibited with CTA091; AIC, Akaike’s Information Criterion.

Discussion

This is the first report of 1,25(OH)2D3 concentrations in tumor xenografts, and how the plasma and tumor distribution of 1,25(OH)2D3 can be increased independently by CTA091, a selective CYP24 inhibitor.

The 1,25(OH)2D3 catabolizing enzyme CYP24 is expressed in normal tissues including the kidney [11], which affects 1,25(OH)2D3 plasma pharmacokinetics, and in H292 tumors [Fig. 1], which may independently affect local tumor exposure to the steroid. Therefore, we hypothesized that CTA091 could separately impact the elimination of 1,25(OH)2D3 from the central (plasma) compartment, and also inhibit elimination of 1,25(OH)2D3 from the tumor itself. We indeed observed an increase in murine 1,25(OH)2D3 plasma AUC and Cmax of 1.5 and 1.6-fold, respectively, after co-administration of CTA091 and 1,25(OH)2D3, which agrees with a previously reported increase in rat serum 1,25(OH)2D3 exposure and Cmax of 1.4-fold and 1.5-fold, respectively, after 500 µg/kg CTA091 [24]. A similar effect of pharmacologic CYP24 inhibition on 1,25(OH)2D3 plasma PK was observed in studies conducted by Muindi et al [28]: Co-administration of 1,25(OH)2D3 with ketoconazole, a general inhibitor of P450 enzymes including CYP24, resulted in a 1.3-fold increase in 1,25(OH)2D3 serum AUC. We build upon this prior work by demonstrating that tumors which express CYP24 eliminate 1,25(OH)2D3 in vivo, and that an additional consequence of systemic pharmacologic CYP24 inhibition appears to be the preferential suppression of local tumor-mediated catabolism of 1,25(OH)2D3.

The higher ratio of tumor versus plasma AUC of 1,25(OH)2D3 in the presence of CYP24 inhibitor CTA091 suggests that CTA091 has an effect on the tumor disposition of 1,25(OH)2D3 independent of its effect on the plasma disposition (Table 2). By compartmental modeling, we were able to derive 1,25(OH)2D3 pharmacokinetic parameters and parameters to quantitate the effects of CTA091 on 1,25(OH)2D3 pharmacokinetics (Table 3). CTA091 administration resulted in a significant 20% decrease in plasma clearance of 1,25(OH)2D3 (K10*Fp/k10 = 0.81) and a significant 46% decrease in tumor clearance (ktc/(ktc+ ktumor elim) = 0.54). Thus, the effect of CTA091 on tumor 1,25(OH)2D3 exposure is larger than its effect on plasma 1,25(OH)2D3 exposure. This may be explained by the pharmacokinetics of CTA091 itself, which is cleared from plasma more rapidly than 1,25(OH)2D3 (personal communication, M. Petkovich). Retention of CTA091 in tumor may therefore prolong the local CYP24 inhibition, while systemically, the CYP24 inhibition is likely to be shorter and less pronounced. This also highlights that the currently applied compartmental model, which assumes a constant inhibitory effect of CTA091 on CYP24, is an oversimplification. However, only with more detailed information about CTA091 disposition can the model be further refined. Next generation CYP24 inhibitors should be designed to be metabolically more stable, which will allow for more durable increases of 1,25(OH)2D3 tissue exposure. Alternatively, 1,25(OH)2D3 exposure may be increased by repeated dosing of a less stable CYP24 inhibitor.

Theoretically, CTA091 treatment could have instead resulted in a preferential increase in 1,25(OH)2D3 levels in tumors because it induced local expression of the 1,25(OH)2D3-synthesizing enzyme, CYP27B1. To explore this possibility, we did examine the effect of CTA091 treatment on CYP27B1 mRNA expression. CYP27B1 is expressed at very low, but detectable levels in H292 cells. CTA091 alone had no effect on expression in vitro, nor was CYP27B1 modulated in cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 plus CTA091 (data not shown). These negative findings lend further support to the notion that CTA091 exerts its effects in the H292 xenograft model through CYP24 –mediated inhibition of 1,25(OH)2D3 catabolism rather than through the stimulation of 1,25(OH)2D3 production. A different result could be obtained in a tumor model system which expresses higher basal levels of CYP27B1. In this setting, since CYP24 also acts on the CYP27B1 substrate (25(OH)D3), CYP24 inhibition with CTA091 would be predicted to support endogenous, local hormone production.

In prior studies of 1,25(OH)2D3 plasma pharmacokinetics in non-tumor bearing C3H/HeJ mice, hormone concentrations were determined by radioimmunoassay (RIA) following a bolus ip dose of 1,25(OH)2D3. The 1,25(OH)2D3 Cmax and AUC that were calculated by Muindi et al. [28] are approximately 2-fold higher than those determined in our current study, despite the administration of the same dose of 1,25(OH)2D3 by the same route. The differences may reflect a relative increase in the catabolism of 1,25(OH)2D3 in nu/nu mice compared to C3H/HeJ mice. Significant interstrain differences in vitamin D3 metabolism have been described previously [29].

In its current configuration, the LC-MS/MS plasma assay we developed has a lower limit of quantitation of 100 pg/mL 1,25(OH)2D3 and does not detect endogenous levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 in plasma of nu/nu mice. Literature reported values of serum 1,25(OH)2D3 in untreated mice range from 40 pg/mL in BALB/c mice to 80 pg/mL in C3H/HeJ mice [28–29]. If the baseline serum biochemistry of the mice we used is similar to these, it is not surprising that endogenous 1,25(OH)2D3 levels were not detected. Nonetheless, our assay could be used to provide new information on 1,25(OH)2D3 plasma and tumor pharmacokinetics following exogenous administration. For example, we are the first to quantify intratumoral concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3. Tumor concentrations reached a maximum of 1.7 ng/g 1,25(OH)2D3 in the absence of CTA091 and 4.43 ng/g in its presence. Given that 1 g of tumor has a volume of 1 mL, peak tumor concentrations of 3.8 nM and 10 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 were achieved without or with CTA091, respectively.

Clinical trials show that 1,25(OH)2D3 alone can be safely delivered at high doses (0.5 µg/kg) on a once weekly basis in the oncology setting [30]. It remains to be determined whether single agent 1,25(OH)2D3 (at its maximally tolerated dose) will result in a lower tumor exposure than is achieved by combining 1,25(OH)2D3 with a CYP24 inhibitor (at their maximally tolerated doses) and whether this will translate into meaningful differences in anti-tumor efficacy. The impact of variation in CYP24 expression level on tumor exposure to 1,25(OH)2D3 also remains to be determined. The LC-MS/MS assay described here will be utilized in the future to address these clinically relevant questions.

Highlights.

The vitamin D3 catabolizing enzyme, CYP24, is over-expressed in lung tumors.

To study tumor catabolism of vitamin D3, an LC-MS/MS assay was developed.

Assay results show that lung tumor xenografts locally eliminate vitamin D3.

A CYP24 inhibitor independently increased plasma and tumor exposure to vitamin D3.

CYP24 inhibition is a feasible approach to increase tumor exposure to vitamin D3.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. Julie Eiseman (University of Pittsburgh) for many helpful discussions, Ms. Natalie Alexander for assistance with animal studies, and the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute Writing Group for reviewing an early version of this manuscript. We also wish to acknowledge the scientific contributions and enthusiastic support of our mentor and friend, Dr. Merrill Egorin, who passed away before this work could be completed. This work was supported by R01 CA132844 to PAH. This project used the UPCI Clinical Pharmacology Analytical Facility and was supported in part by award P30CA047904.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abbreviations: 1,25(OH)2D3, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3; FBS, fetal bovine serum; GUS, β-glucuronidase; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry; PK, pharmacokinetics; qPCR, quantitative PCR.

References

- 1.Deeb KK, Trump DL, Johnson CS. Vitamin D signalling pathways in cancer: potential for anticancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(9):684–700. doi: 10.1038/nrc2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guzey M, Sattler C, DeLuca HF. Combinational effects of vitamin D3 and retinoic acid (all trans and 9 cis) on proliferation, differentiation, and programmed cell death in two small cell lung carcinoma cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249(3):735–744. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parise RA, Egorin MJ, Kanterewicz B, Taimi M, Petkovich M, Lew AM, et al. CYP24, the enzyme that catabolizes the antiproliferative agent vitamin D, is increased in lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(8):1819–1828. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen G, Kim SH, King AN, Zhao L, Simpson RU, Christensen PJ, et al. CYP24A1 is an independent prognostic marker of survival in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(4):817–826. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou W, Heist RS, Liu G, Asomaning K, Neuberg DS. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels predict survival in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):479–485. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srinivasan M, Parwani AV, Hershberger PA, Lenzner DE, Weissfeld JL. Nuclear vitamin D receptor expression is associated with improved survival in non-small cell lung cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;123(1–2):30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prosser DE, Jones G. Enzymes involved in the activation and inactivation of vitamin D. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29(12):664–673. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beer DG, Kardia SL, Huang CC, Giordano TJ, Levin AM, Misek DE, et al. Gene-expression profiles predict survival of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Med. 2002;8(8):816–824. doi: 10.1038/nm733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson MG, Nakane M, Ruan X, Kroeger PE, Wu-Wong JR. Expression of VDR and CYP24A1 mRNA in human tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57:234–240. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim B, Lee HJ, Choi HY, Shin Y, Nam S, Seo G. Clinical validity of the lung cancer biomarkers identified by bioinformatics analysis of public expression data. Cancer Res. 2007;67(15):7431–7438. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy SG, Tserng K. Calcitroic acid, end product of renal metabolism of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 through C-24 oxidation pathway. Biochemistry. 1989;28:1763–1769. doi: 10.1021/bi00430a051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomon M, Tenenhouse HS, Jones G. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3-inducible catabolism of vitamin D metabolites in mouse intestine. Am J Physiol. 1990;258(4 Pt 1):G557–G563. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.258.4.G557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henry HL. The 25(OH)D3/1α,25(OH)2D3-24R-hydroxylase: a catabolic or biosynthetic enzyme? Steroids. 2001;66:391–398. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(00)00158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen KS, DeLuca HF. Cloning of the human 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 24-hydroxylase gene promoter and identification of two vitamin D-responsive elements. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1263:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00060-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohyama Y, Ozono K, Uchida M, Yoshimura M, Shinki T, Suda T, et al. Functional assessment of two vitamin D-responsive elements in the rat 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 24-hydroxylase gene. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30381–30385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer MB, Goetsch PD, Pike JW. A downstream intergenic cluster of regulatory enhancers contributes to the induction of CYP24A1 expression by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(20):15599–15610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Endres B, Kato S, DeLuca HF. Metabolism of 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 in Vitamin D Receptor-Ablated Mice in Vivo. Biochemistry. 2000;39:2123–2129. doi: 10.1021/bi9923757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masuda S, Byford V, Arabian A, Sakai Y, Demay MB, St-Arnaud R, et al. Altered pharmacokinetics of 1,α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 in the blood and tissues of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D-24-Hydroxylase (Cyp24a1) Null Mouse. Endocrinology. 2005;146:825–834. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuster I, Egger H, Bikle D, Herzig G, Reddy GS, Stuetz A, et al. Inhibitors of vitamin D hydroxylases: structure-activity relationships. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88(2):372–380. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yee SW, Simons C. Synthesis and CYP24 inhibitory activity of 2-substituted-3,4-dihydro-2Hnaphthalen- 1-one (tetralone) derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14(22):5651–5654. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Posner GH, Crawford KR, Yang HW, Kahraman M, Jeon HB, Li H, et al. Potent, low-calcemic, selective inhibitors of CYP24 hydroxylase: 24-sulfone analogs of the hormone 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;89–90(1–5):5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuster I, Egger H, Herzig G, Reddy GS, Schmid JA, Schussler M, et al. Selective inhibitors of vitamin D metabolism--new concepts and perspectives. Anticancer Res. 2006;26(4A):2653–2668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kahraman M, Sinishtaj S, Dolan PM, Kensler TW, Peleg S, Saha U, et al. Potent, selective and low-calcemic inhibitors of CYP24 hydroxylase: 24-sulfoximine analogues of the hormone 1α,25- dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Med Chem. 2004;47(27):6854–6863. doi: 10.1021/jm040129+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Posner GH, Helvig C, Cuerrier D, Collop D, Kharebov A, Ryder K, et al. Vitamin D analogues targeting CYP24 in chronic kidney disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121(1–2):13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herrera LJ, El-Hefnawy T, Queiroz de Oliveira PE, Raja S, Finkelstein S, Gooding W, et al. The HGF receptor c-Met is overexpressed in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Neoplasia. 2005;7(1):75–84. doi: 10.1593/neo.04367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D'Argenio DZ, Scumitzky A. ADAPT II user's guide: pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic systems analysis software. Los Angeles: University of Southern California; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akaike H. A Bayesian extension of the minimal AIC procedures of autoregressive model fitting. Biometrika. 1979;66:237–242. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muindi JR, Modzelewski RA, Peng Y, Trump DL, Johnson CS. Pharmacokinetics of 1α,25- dihydroxyvitamin D3 in normal mice after systemic exposure to effective and safe antitumor doses. Oncology. 2004;66:62–66. doi: 10.1159/000076336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misharin A, Hewison M, Chen CR, Lagishetty V, Aliesky HA, Mizutori Y. Vitamin D deficiency modulates Graves' hyperthyroidism induced in BALB/c mice by thyrotropin receptor immunization. Endocrinology. 2009;150(2):1051–1060. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beer TM, Munar M, Henner WD. A Phase I Trial of Pulse Calcitriol in Patients with Refractory Malignancies. Cancer. 2001;91:2431–2439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]