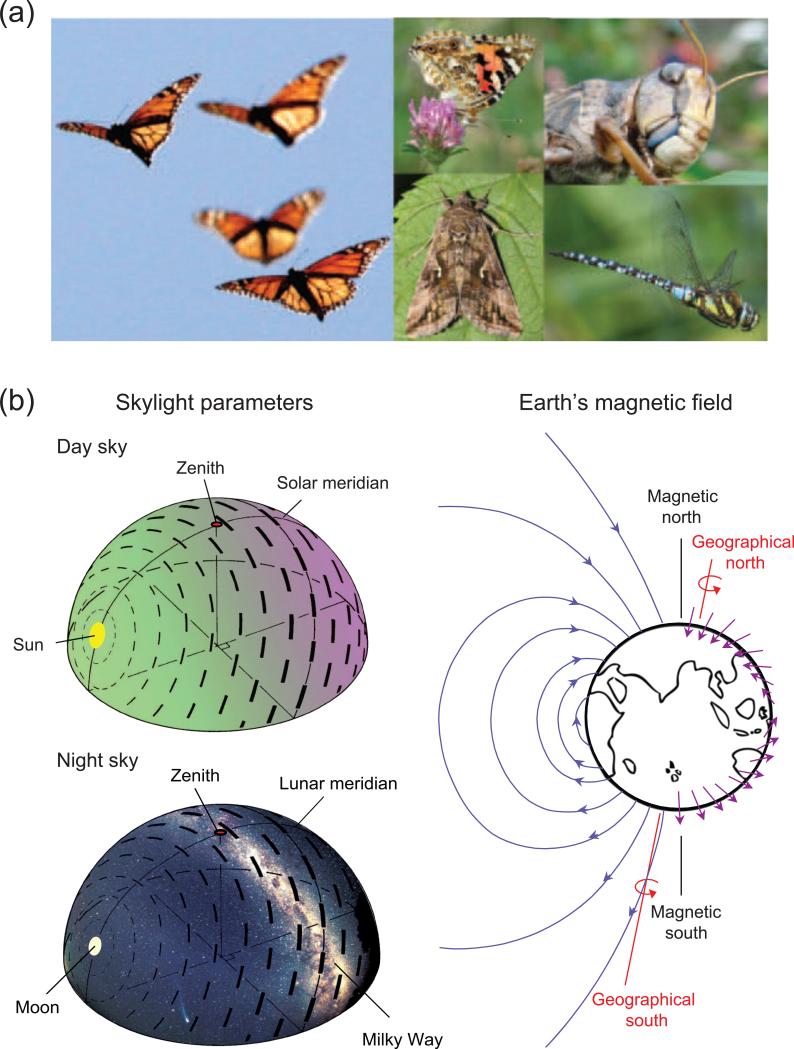

Figure 1. Sensory cues used for long-distance orientation by migratory insects.

(a) Several insect species undergo seasonal long-distance migration, including (from left to right) the monarch butterfly, other day-active butterflies, nocturnal moths, the desert locust, and dragonflies. Monarch picture: courtesy of Monarch Watch (www.monarchwatch.org). (b) Migratory insects exploit environmental cues for long-range navigation. (Top left) Migrants flying during the day can extract directional information from the sun position in the sky (yellow oval), as well as the derived patterns of polarized skylight (E-vector; dashed lines) and the spectral gradient, which ranges from longer wavelengths of light (green) dominating in the solar hemisphere to shorter wavelengths (violet) dominating in the antisolar hemisphere. The bar thickness of dashed lines represents the degree of polarization, while the bar orientation represents the angle of polarization relative to solar position as viewed from the center of the celestial sphere. Modified from [20••]. (Bottom left) The moon and its polarization pattern, stars and the Milky Way are celestial cues available to migratory insects flying at night. (Right) The Earth's magnetic field emerges from the southern hemisphere, wraps around the globe and re-enters at the northern hemisphere (blue lines). Migrating animals can extract directional information (compass sense) and positional information (map sense) from the polarity, inclination and intensity of the Earth's magnetic field, which are gradually changing across the Earth's surface (represented by the angle and length of the violet arrows). Modified from [41].