Abstract

Background

The paper reports on the importance of the interpersonal nexus within qualitative research processes, from a recent research project on patient experiences of shoulder surgery. Our aim is to reveal the importance of qualitative research processes and specifically the role of the interpersonal nexus in generating quality data. Literature related to the importance of human interactions and interpersonal communication processes in health-related research remains limited. Shoulder surgery has been reported to be associated with significant postoperative pain. While shoulder surgery research has investigated various analgesic techniques to determine key efficacy and minimization of adverse side effects, little has been reported from the patient perspective.

Methods

Following institutional ethics approval, this project was conducted in two private hospitals in Victoria, Australia, in 2010. The methods included a survey questionnaire, semistructured interviews, and researcher-reflective journaling. Researcher-reflective journaling was utilized to highlight and discuss the interpersonal nexus.

Results

This research specifically addresses the importance of the contributions of qualitative methods and processes to understanding patient experiences of analgesic efficacy and shoulder surgery. The results reveal the importance of the established research process and the interwoven interpersonal nexus between the researcher and the research participants. The interpersonal skills of presencing and empathetic engagement are particularly highlighted.

Conclusion

The authors attest the significance of establishing an interpersonal nexus in order to reveal patient experiences of shoulder surgery. Interpersonal emotional engagement is particularly highlighted in data collection, in what may be otherwise understated and overlooked qualitative findings in patient experiences of shoulder surgery.

Keywords: interpersonal, qualitative research, pain management, patient experiences, shoulder surgery

Introduction

This article emerges from a research project entitled “An investigation of postoperative analgesic efficacy following shoulder surgery and its relationship to hospital length of stay” which took place in 2010 in Victoria, Australia. The project investigated 75 patients’ experiences with pain and its management following shoulder surgery. The methods used were an in-person survey questionnaire, semistructured interviews, and researcher-reflective journaling.

For over a decade, shoulder surgery has been reported to be associated with significant postoperative pain.1–3 While research has investigated various analgesic techniques to determine key efficacy and minimization of adverse effects, little has been reported from the patient perspective. Further, while qualitative research is central to developing knowledge of patients’ experiences, the relationship between the researcher and the researched, and the embedded interpersonal nexus, is often understated and overlooked.

In order to explore the importance of interpersonal relationships within research processes, one initially needs to consider the current context for health care research where such a discussion is located. This context includes ever-increasing evidenced-based research, knowledge translation, and the continued dominance of quantitative research.

Context of health care research

While evidence-based practice continues to be upheld as a key strategic intervention for improved quality health outcomes,4,5 its uptake into practice by health care professionals remains protracted and inconsistent.4–6 It is apparent that the majority of health care providers do not consistently practice within any evidence-based frameworks7,8 nor adopt the science of knowledge translation.9

When considering research credibility, scientific quantitative research projects worldwide continue to be perceived as more significant than qualitative projects. Therefore, qualitative researchers are confronted by increasing competitiveness in their quest for funded projects. A strategy utilized by some qualitative researchers is to incorporate quantitative nuances and discourse10 into their project designs where researchers and the researched alike are human beings neutralized as social units.11 Accordingly, the embedded methodologies are found within the ambit of mixed-method studies rather than stand-alone qualitative projects.

Therefore, despite the discourse on the importance of patient experiences in health care, qualitative research remains at best abutted and on the periphery,12 while evidence and numbers retains dominance in research hierachies.13 It is without doubt that methodological tension still exists between quantitative and qualitative research approaches.12

It is imperative that health professionals question whether the dominant current health research methodologies and research designs are meeting the needs of practicing nurses, particularly as the uptake of knowledge to action remains limited. And, if subjective patient experiences are of critical value to health care and underpin competent care,13 why do scholars still need to debate the merits of qualitative research processes?

Importance of qualitative approaches

While debates on quantitative versus qualitative research have proliferated throughout the health literature for decades, and methodologies should be determined by the research question, decisions regarding methodological approaches remain in contention. Arguably, research as a means of generating knowledge in nursing should utilize many ways of understanding, yet be both integrated and balanced such that too much empirical knowledge may result in control and manipulation.14 As a means of generating knowledge, qualitative research claims that knowledge is centered on people, and the expression of their personal awareness or subjectivity is valued to the point that it is integral to the meaning of the research.15 People are acknowledged as crucial sources of information and, unlike quantitative research, any knowledge that counts as truth does not have to be free from the subjectivity of the researcher.15

Therefore, qualitative research has a unique ability and, indeed, one of its strengths is to establish a relationship or nexus between the researcher and the researched.16 By focusing on a nexus, important aspects of knowledge are explored that would normally defy traditional quantitative approaches. The relationship between the researcher and individual research participants is a key aspect of the research process and, when identified as such, can have an unexpected empowering end result and/or become recognized as a therapeutic tool, as is oftentimes seen with critical and action research methodologies.17–19

Therefore, researchers need to reflect upon the merit of an interpersonal nexus and its role in centrally supporting and valorizing patient participants with their individual disclosures. Furthermore, the ability of the researcher to focus on interpersonal interactions does supplicate questions and highlight preassumptions regarding the skills of researchers. For instance, it is advantageous for researchers to reflect upon their interpersonal style and the degree to which they may be highly skilled and engaged, or conversely, impartial and distant from their research participants. Reflections should further include whether researchers are able, comfortable, and skilled to extend a traditional 1-hour interview to one that comprehensively explores patients’ experiences on the topic in question. And, most critically, will the sought interpersonal nexus and the required empathetic engagement with participants’ perceived vulnerability be achieved. Regrettably, for some researchers, the development of the interpersonal relationship is held in dialectic tension, with a focus on the technical aspects of qualitative interviews and consequently the importance of the interactions between researcher and participants remain understated and overlooked. With a poor understanding of qualitative research processes, qualitative research may be viewed as requiring less skill than quantitative analysis. Taking these issues into consideration, the value of an interpersonal nexus in the relationship between the researcher and the participant requires further discussion.

Research processes

In the conduct of research projects, qualitative researchers ensure the way the research is conducted is of equal importance to their data collection. Qualitative researchers ensure participants’ voices are sustained while safeguarding their identity/visibility at all costs. It is never ideal to attempt to “do the right thing”; rather, qualitative researchers are committed to validating the participants’ opinions, thoughts, and feelings for the duration of the project. Their interpersonal skills utilized in interactions with their participants form the nexus, and are pivotal to the research process.

Interpersonal nexus

Relationships between the researcher and the researched need to be managed conscientiously because these relationships can be complex and fraught with moral and ethical dilemmas.21 Such complexities are heightened when the researcher is a health professional researching active health care recipients,21 so ethical care in each interaction is paramount.

In order to improve quality care, qualitative researchers are required to remain focused on establishing meaning22 by utilizing interpersonal presencing23 and personal immediacy11 rather than distance themselves. To ensure rich data, the researcher’s “self ” needs to be intricately involved in the research process and the interactions with the participants.22,23 Therefore, the researcher’s self becomes an important resource in the research.22 Each interaction should be fundamentally relational and visibly be an ethical moment of care.24

To ensure freedom in the interactions, a conversational approach will begin the necessary connection between the research and the participant.25 Uniting and building on these professional interactions with a focus on emotional safety and interpersonal engagement will work towards achieving an effective interpersonal nexus between the researcher and each participant. The aim is always to “give shape and expression to what would otherwise be untold”,26 while carefully recognizing the emotions and any motives for the interactions.22 Further, researcher values, beliefs, and emotions need to be accepted as central to the achievement of an interpersonal nexus. Any attempt to discount the importance of the personal presence of the researcher will typify objective reality, with the assumption that the research can be repeated by anyone using the scientific method.21

Qualitative interviews exploring sensitive topics are moderated by emotional engagement,16,22 and as such, also need to be embodied performances. However, performances alone are not enough. Qualitative researchers need to ensure that the interpersonal relationship is not limited to the interview alone.

Ensuring an interpersonal relationship for the duration of the research project, enhanced by the researcher’s reflexivity and engagement with the emotional embodied and performed dimensions of the interview,16 will result in more comprehensive and rich data.

Careful reflection on the emotional framing of interviews to achieve an effective interpersonal nexus is critical in reaching a far deeper understanding and/or perception of the participant’s experience. Such framing would incorporate the consistent utilization of highly developed interpersonal skills by the researcher, and this would be apparent from participant selection to completion of the project. More specifically, the interpersonal skills of active presencing, listening, and empathetic engagement are critical in supporting participant expressions that include sensitive disclosures.22

As qualitative research is becoming more open to diverse forms of demonstrating quality in research processes,27 and become increasingly recognized as a legitimate form of knowledge expression,12 expectations for the interpersonal nexus to be examined and articulated fully will become more imperative.

Research project

An example of the importance of qualitative findings, and specifically the interpersonal nexus, was revealed in the research project on shoulder surgery. The research project was designed to investigate the parameters of analgesic efficacy and improve clinical practice.1–3

The identified parameters of the research were patient experiences of surgical care, pain, and perception of pain management of analgesic treatment. The study utilized mixed methods, being both a quantitative and qualitative study. This included an in-person paper-based survey questionnaire (n = 75) and interviews (n = 15) with patients. To be able to enhance an interpersonal nexus, the researcher identified the importance of incorporating visual observation into the project, and this specifically triggered further engagement with research participants.28

Following institutional ethics approval, the project was explained to 78 patients, with three patients declining to participate. This study was conducted in two private hospitals in Victoria, Australia, in 2010 across four data collection sites. This paper specifically reports on the research processes related to collecting the data and excerpts from the researcher’s reflective journal. Therefore, visual observation and researcher-reflective journaling was conducted with all participants (n = 75).

Importance of research process: key findings

The project commenced with the researcher having the intent to establish an interpersonal nexus. This was readily received by each participant, who showed a strong interest in the project and willingness to participate. The nexus was actioned by the researcher and was evidenced particularly by presencing and empathetic engagements within the interactions.

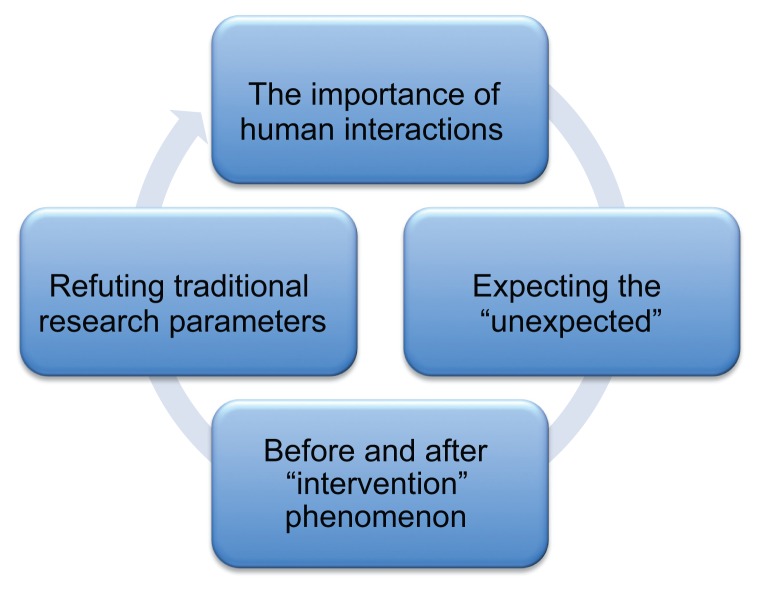

Following thematic analysis of the reflective journal, the research elicited four specific elements related to the research process. These are outlined in Figure 1, were the importance of human interactions, expecting the unexpected, the before and after “intervention” phenomenon, and refuting traditional parameters.

Figure 1.

Research process: Key findings.

While all elements initially occurred sequentially, each had an integral effect on the next element that transpired. Therefore, there was a domino effect. The human interactions established a platform for the researcher to respond to any unexpected circumstances with participants. In turn, these two elements collectively became essential requisites for the phenomena of researcher/participant interventions and overall refuting traditional parameters of mixed-method studies. The following outlines the elements.

Importance of human interactions

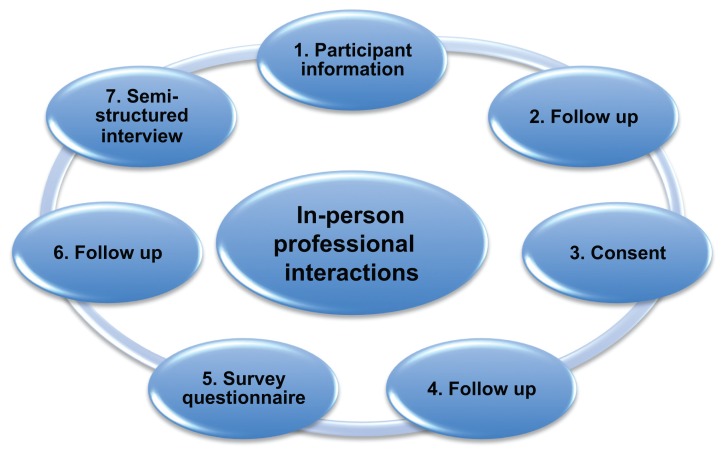

While there were many interactions with each participant, the process of conducting this research included seven specific inperson interactions (see Figure 2). The researcher, a professor of nursing, conducted all interactions related to data collection. Because the aim was to establish and sustain the interpersonal nexus, close interpersonal engagement with the participants occurred in-person at the bedside. As such, demedicalized environments of familiarity were intentionally created,29 and the positive effect of the interactions was pervasive and fuelled each subsequent communication. For instance, the researcher reflections revealed:

Figure 2.

The importance of human interactions.

Researcher: “Each patient’s environment feels really right. The way I am interacting with each person and equally each person with me seems to exemplify a friendly, easy sort of communication. I know I have consciously attempted to ensure each person feels relaxed and is able to ask any questions whenever they feel like it, however this action reaches another dimension when it works this way. Even though each participant is about to have surgery or they are just at their first day postoperatively, they want to engage and talk about themselves – something about their pain and the effects of their surgery or something unrelated that is personal.”

It was evident that the distant detached nonparticipant observer was antithetical to the process. The semistructured interview schedule and questions lost their centrality as patients initiated discussions, led conversations, and reciprocity ensued. The consistency that was evident with the same researcher continually engaging with each participant for the duration of the project built trust and, as such, each person involved was able to share his or her experiences freely. The researcher’s journal elucidated this finding:

Researcher: “Participants were pleased to see me back each time, asking me where I had been, what had I been doing and repeatedly they seemed really interested in the research. While I had a strong desire for this to occur, I am still surprised that many participants are interested in this project. Often they asked how many participants had joined the study and what was I finding with other participants. When I was able to respond by saying, the interest is increasing and how many new participants had consented, this engagement seemed to create a safety for a continued dialogue. While I needed to be conscious of what was shared in terms of confidentiality and protecting all participants, the sharing that I did seemed to create the environment necessary for the participants to openly shared how they felt they were managing their pain and asked for my opinion on their progress.”

Participants consistently wanted to tell their stories and not be constrained by a survey or a proposed short interview. However, discussions initiated by participants often began with a professional comment and followed with something personal, such as:

“Oh you are a professor of nursing, how do you get to be a professor? Do you work at the hospital or the university? Do you like your job, where do you live”? And, “Why do you want to research this topic? Do you have funding for this type of research? Have you had a shoulder injury”? And, “I didn’t know nurses do research, don’t all nurses just look after patients? Do you care for patients too or just do research? How long have you worked with shoulder problems? What other research have you done? Why do you do research? Isn’t it more satisfying to work with patients?”

Expecting the unexpected

Even though the researcher was experienced and aware that “the novice sees virtually everything, while the expert knows what to neglect”,30 her experience indicated she should be attuned to acknowledge that situations will always occur that are otherwise unexpected.

The surprising events that occurred in this research were that although there was enthusiasm for the topic, and participants were unrelenting in their participation, nearly all were more interested in discussing their “in the moment” experiences and human interactions. Therefore, even though their interest in the research remained high, the survey questionnaire and proposed interviews were not as engaging as was conversing about their shoulder surgery and their pain management, and equally anything unrelated to a personal dimension. Furthermore, because the researcher was mindful that researchers who are professional nurses can influence researcher–participant interactions, she carefully balanced the personal interactions with the actual topic of the research to ensure the required data were collected.31 Therefore, the “unexpected” was responded to as a positive influence.31

An example of this situation is the following:

Participant: “Oh I’m so pleased you are here, I want you to meet my family and they are all here. My wife and my daughter have read all of your paper work. My daughter is getting married next week. Do you think I will be home for the wedding?”

Researcher: “Hi, it’s excellent to meet you, I have heard a lot about you.”

In response to directing the questions back to the research, the researcher responded:

“You do look well and seem to be moving freely, but the final decision about your discharge rests with your doctor. How is your pain today?”

Of further great significance was that most participants “brought forward” their interview. Although they were willing to be interviewed following discharge and consented to this occurrence, on discharge most had willingly initiated responses to all of the interview questions before the planned interview. The following is an example from a participant:

Participant: “I have read all the questions, why don’t you sit down because I want to tell you my answers now. It’s okay if you want to ring me in a few days for a phone interview as well but I want to tell you now.”

Before and after “intervention” phenomenon

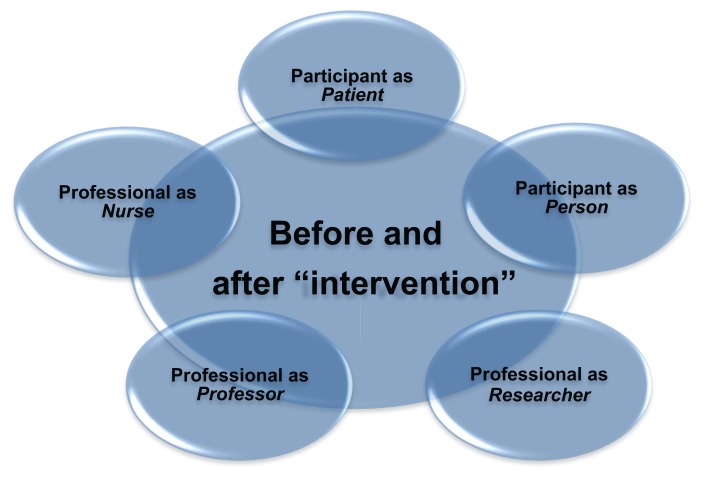

The third element was termed an intervention to emphasize the ways in which the researcher and participants interacted smoothly within their multiple roles. In relation to the participants, each engagement brought forward the participant as a person as well as patient, and the researcher was also a professor and a nurse.

Therefore, irrespective of professional interactions (see Figure 2), the researcher and participants combined to generate a complex phenomenon in interactions. It is also identified as “before and after” to bring out the importance of the nexus wherein prior to the interactions occurring, there were a project, a researcher, and possible participants, and afterwards there was a collaborative ethic of care.21

Following each interaction where each role was distinguished, a positive relationship ensued and the nexus was strengthened. Because the researcher was a health professional, possessing knowledge of the patient health and illness status, she was able to manage multiple roles in patient interaction while continuing to recognize appropriate research questions with each intervention.32 The roles which formed the scaffold for the interventions are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Before and after “intervention” phenomenon.

As has been evident in other health-related research,29 each participant predominantly wanted to be perceived as a person rather than as a patient. While this research was focused directly on inpatients undergoing surgery, each participant brought forward their “personhood” into the interactions. They spoke of their careers and brought those aspects forward, indicating its importance to the research. For instance, one participant said:

“I’ve worked as a researcher. I used to work at the NHMRC (National Health Medical Research Council). What type of funding did you receive for this project? Was it competitive? I see this is a mixed-method study, why did you choose a qualitative component as well?” Another shared, “I’ve got a masters in engineering, I was thinking about doing a PhD, do you think it is worth it given I work in industry? I know it’s important if you are employed in a university.”

In terms of the researcher, her multiple roles blended expertise in health, research, and academia which resulted in her straddling both an emic perspective and an etic perspective. 20 Possessing knowledge of rules and regulations that control the function of the health care organization, the researcher was able to utilize this knowledge in her reflections and evaluation of the clinical milieu from multiple different perspectives and accordingly be “street smart” in her interactions.32 In her journal she wrote:

“This research seems like an ethnography. In order to capture my data I need to be acutely aware of the functioning of each unit and ward, the ‘slick’, efficient operations of each nurse manager, the office manager, the timing of doctors’ rounds and moving within and around so I am not in the way. I need to be respectful that this is not my place of work yet show I have the knowledge and ability to independently conduct my research.

“Most participants want to interact as people and not be confined to a patient/sick role. They consistently want to show to me they are people with key family and work responsibilities too. Together ‘we’ bring our many aspects, it is like a phenomena yet it is conditional on a seamless acknowledgment and respect that the participant is a person as well as a patient. Together these roles and what I can provide as a nurse, researcher, and professor create a positive effect.”

Refuting traditional parameters

The final element concerns a rebuttal of the traditional notions of collecting data. The findings from the research processes revealed that stereotypical mixed methods were overridden by explicit participant engagement within the study. Participants had a strong desire to be very involved, akin to being a research partner, and the interpersonal processes of researcher/participant connection strengthened the research dialogs within each interaction.

As the researcher’s empathetic engagement was sustained, participants willingly shared, often in great intensity, their up-to-date experiences with shoulder surgery and pain management. As referred to earlier, they were prepared and did share their interview responses before discharge, even when they had prearranged a home interview. Participants’ desire to share their opinions “in their moment” was strong and they did not want to hold their thoughts and feelings related to any prescribed timing. While it could be argued that participants orchestrated their interview schedules, the authors claim that research participants felt comfortable to share at any point in the professional interaction. For instance, the following comments demonstrate participant involvement and willingness to disclose:

“I’ve been rereading my survey and my interview questions. I’d be okay if we completed both together, is this okay with you? I want to discuss my medications with you and how I found managing the machine for my pain [patient-controlled analgesia]. You will see it’s been removed since I last saw you yesterday but I have had some quite bad pain. I can’t understand why I still have pain and feel quite ‘flat’ about it. You will know because you’re a professor and like a consultant.”

As such, these findings call into question assumptions regarding prescribed views for the conduct of research and highlight the importance of the interpersonal nexus between the researcher and the participant to accommodate flexibility in research processes. It also raised a conflict of interest, because in this situation; the researcher was not interacting with the participant in the capacity of a nurse. Accordingly, the researcher responded with the following comment to the participant:

“While I am a nurse, I cannot comment on your pain and suggest any recommendations other than it is important to discuss this with your nurse. I can ask her to come in to see you now if you would like.”

Most profoundly, patients’ experiences elicited in interviews were paramount in determining the parameters of analgesic efficacy and improving clinical practice, but the patients’ desire was to engage in greater depth. Stories unfolded with the engagement of human interactions between the researcher and the participants.

Conclusion

It is critical for qualitative researchers to reflect on the process, assumptions, and what researchers do and can do in new and interesting ways.30,32 Quantitative nuances, whilst seductive to the novice researcher or funding seeker, are frequently antithetical to the research goal and the ability to gain depth and meaningful data.

In this project, researcher reflexivity played a key role in participant engagement. The researcher “actioned” what to focus on and what to neglect.30 Being prepared for the unexpected opened up the study and extended possibilities for human interaction within the health research context. Therefore, the contributions of qualitative methods to understanding patient experiences of analgesic efficacy and shoulder surgery include an exploration of the role of reflexivity and human engagement, and being prepared for the unexpected.

The skills and expertise required to undertake qualitative research should not be underestimated, even if the dominant discourse argues that “there are just a few interviews”. Empathetic engagement and presencing that contributed to the interpersonal nexus was paramount and consistently strengthened with each layer of intervention.

Similar to many qualitative research studies, self-reporting may be considered a study limitation. The use of reflexivity is therefore paramount and further suggests that qualitative research requires a high level of skill and expertise.23 The authors attest and suggest the importance and significance of establishing an interpersonal nexus in all personal interview-based research. Further research of the interpersonal nexus is warranted. Within this study, patients talked freely, revealing their experiences of shoulder surgery. The interpersonal emotional engagement is particularly highlighted by the data collection in what may be otherwise understated and overlooked qualitative findings on patient experiences of shoulder surgery.

Acknowledgments

Andrea Callaghan, Narelle Davis, Anne Hofmeyer, and Robyn Wall are thanked for their contribution to the research design. The Australian Catholic University and St Vincent’s Mercy Private, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, are also thanked for their contribution to funding.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Adam F, Menigaux C, Sessler DI, Chauvin M. A single preoperative dose of gabapentin (800 milligrams) does not augment postoperative analgesia in patients given interscalene brachial plexus blocks for arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Anesth Analg. 2006;103(5):1278–1282. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000237300.78508.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richman JM, Liu SS, Courpas G, et al. Does continuous peripheral nerve block provide superior pain control to opioids? A meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2006;102(1):248–257. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000181289.09675.7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singelyn FJ, Lhotel L, Fabre B. Pain relief after arthroscopic shoulder surgery: A comparison of intraarticular analgesia, suprascapular nerve block, and interscalene brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:589–592. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000125112.83117.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitson AL, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARIHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges. Implement Sci. 2008;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, Mays M. The evidence based practice beliefs and implementation scales: psychometric properties of two new instruments. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2008;5(4):208–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2008.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kent B, McCormack B. Context in context. In: Kent B, McCormack B, editors. Clinical Context for Evidence-based Nursing Practice. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pravikoff DS, Tanner AB, Pierce ST. Readiness of US nurses for evidence-based practice. Am J Nurs. 2005;105(9):40–51. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200509000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shirey MR. Evidence-based practice: How nurse leaders can facilitate innovation. Nurs Adm Q. 2006;30(3):251–265. doi: 10.1097/00006216-200607000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kent B, Hutchinson A, Fineout-Overholt E, Williamson K. Strategies for translating knowledge into practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2009;6(4):246–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2009.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voronov M, Singer J. The myth of individualism-collectivism: A critical review. J Soc Psychol. 2002;142(4):461–480. doi: 10.1080/00224540209603912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yannaras C. The Freedom of Morality. Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorne S. Toward methodological emancipation in applied health research. Qual Health Res. 2011;21(4):443–453. doi: 10.1177/1049732310392595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morse JM. How different is qualitative health research from qualitative research? Do we have a subdiscipline? Qual Health Res. 2010;20(11):1459–1468. doi: 10.1177/1049732310379116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chinn P, Kramer M, Maeona K. Integrated Knowledge Development. 7th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson-Tench M, Taylor B, Kermode S, Roberts K, editors. Research in Nursing and Health Care: Evidence for Best Practice. 4th ed. South Melbourne, VIC: Cengage Learning; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ezzy D. Qualitative interviewing as an embodied emotional performance. Qual Inq. 2010;16(3):163–170. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pannowitz HK, Glass N, Davis K. Resisting gender-bias: Insights from Western Australian middle-level women nurses. Contemp Nurse. 2009;33(2):103–119. doi: 10.5172/conu.2009.33.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer J. Using qualitative methods in health related action research. Br Med J. 2000;320(7228):178–181. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7228.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose J, Glass N. The importance of emancipatory research to contemporary nursing practice. Contemp Nurse. 2008;29(1):8–22. doi: 10.5172/conu.673.29.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards H, Emslie C. The “doctor” or the girl from the university”? Considering the influence of professional roles on qualitative interviewing. Fam Pract. 2000;17(1):71–75. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hewitt J. Ethical components of researcher-researched relationships in qualitative interviewing. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(8):1149–1159. doi: 10.1177/1049732307308305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glass N. Interpersonal Relating: Health Care Perspectives on Communication, Stress and Crisis. Melbourne, VIC: Palgrave Macmillan; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holloway I, Biley F. Being a qualitative researcher. Qual Health Res. 2011;21(7):968–975. doi: 10.1177/1049732310395607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noddings N. Educating Moral People: A Caring Alternative to Character Education. Williston, VT: Teachers College Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis K, Taylor B. Stories of resistance and healing in the process of leaving abusive relationships. Contemp Nurse. 2006;21(2):199–208. doi: 10.5172/conu.2006.21.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Witherell C, Noddings N. Stories Lives Tell: Narrative and Dialogue in Education. New York, NY: Teachers College, Columbia University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roulston K. Considering quality in qualitative interviewing. Qual Res. 2010;10(2):199–228. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarr J, Thomas H. Mapping embodiment: Methodologies for representing pain and injury. Qual Res. 2011;11:141–157. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phelps C, Herrigan D, Protheroe L, Hopkin J, Jones W, Murray A. “I wouldn’t classify myself as a patient”: The importance of “well-being’ environment for individuals receiving counseling about familial cancer risk”. J Genet Couns. 2008;17(4):294–305. doi: 10.1007/s10897-008-9158-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuzel A. Commentary 1 – the importance of expertise. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(11):1464–1465. doi: 10.1177/1049732310379117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jack S. Guidelines to support nurse-researchers reflect on role conflict in qualitative interviewing. Open Nurs J. 2008;2:58–62. doi: 10.2174/1874434600802010058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morse JM. How different is qualitative health research from qualitative research? Do we have a subdiscipline? Qual Health Res. 2010;20(11):1459–1468. doi: 10.1177/1049732310379116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]