Abstract

Objective

Tasks involved in sickness certification constitute potential problems for physicians. The objective in this study was to obtain more detailed knowledge about the problems that general practitioners (GPs) experience in sickness certification cases, specifically regarding reasons for issuing unnecessarily long sick-leave periods.

Design

A cross-sectional national questionnaire study. Setting. Primary health care in Sweden.

Subjects

The 2516 general practitioners (GPs), below 65 years of age, who had consultations involving sickness certification every week. This makes it the by far largest such study worldwide. The response rate among GPs was 59.9%.

Results

Once a week, half of the GPs (54.5%) found it problematic to handle sickness certification, and one-fourth (25.9%) had a patient who wanted to be sickness absent for some reason other than medical work incapacity. Issues rated as problematic by many GPs concerned assessing work capacity, prognosticating the duration of incapacity, handling situations in which the GP and the patient had different opinions on the need for sick leave, and managing the two roles as physician for the patient and medical expert in writing certificates for other authorities. Main reasons for certifying unnecessarily long sick-leave periods were long waiting times in health care and in other organizations, and younger and male GPs more often reported doing this to avoid conflicts with the patient.

Conclusion

A majority of the GPs found sickness certification problematic. Most problems were related to professional competence in insurance medicine. Better possibilities to develop, maintain, and practise such professionalism are warranted.

Key Words: GP, physicians, primary health care, sickness certification, sick leave

According to a nationwide survey in Sweden, tasks involved in sickness certification constitute potential problems for GPs.

Most of the GPs considered assessments of work capacity to be very or fairly problematic.

At least once a month, most of the GPs issued sickness certificates for longer periods than they deemed necessary.

Younger GPs and male GPs more often issued unnecessarily long sick-leave periods in order to avoid conflict with the patient.

Background

In Sweden, to be eligible for sickness benefit after one week of self-certification, a medical certificate issued by a physician is required. That document will have a substantial impact on the decision made by the employer, or, after two weeks of sick leave, by the Social Insurance Office (SIO), as to whether the person ill or injured fulfils the criteria for receiving sickness benefit.

Consultations regarding sickness certification involve a number of different tasks [1,2]. A systematic review of published studies established that physicians experience sick-listing tasks as problematic [3]. This was also confirmed by some later investigations [4–8]. In addition, studies have shown that physicians report wanting more knowledge and skills in this area [9–11]. As sickness certification is a common task among general practitioners (GPs) in Sweden [3], as well as in other Western countries [12], it is particularly important to gain more knowledge regarding this for GPs.

The problems that GPs experience include assessment of work incapacity, estimation of length and degree of certification, conflicting roles, and resolving conflicts with patients over sickness certification [2,4,13,14]. Furthermore, GPs tend to be influenced by how the patients describe their problems [15–17] and there are findings [18] indicating that long experience of family medicine was associated with issuing more sickness certificates. It has also been reported that physicians issue sickness certificates for longer periods than necessary due to excessively long waiting times in both the health care system and other organizations [6,19]. Some of the dilemmas they encounter in this area have been described by other investigators [20,21], and many GPs lack support in handling these matters [13,22].

There is still a need for more detailed knowledge on the frequency regarding different sickness certification problems perceived by a larger population of GPs. Such information can be used to provide better support for GPs in developing optimal professional practice concerning these tasks [2,23].

The objectives of the present study were as follows: to further elucidate the frequency and severity of various problems that GPs experience when handling sickness certification of patients, and to determine how often and for what reasons GPs in some cases issue sick notes for longer periods than necessary.

Material and methods

A comprehensive questionnaire was developed to address physicians’ work in handling sickness certification cases. The questionnaire was based on the results of previous investigations and a pilot study, as well as discussions with clinicians and other researchers [1,2,4,13]. The questionnaire was sent to the home addresses of all 36 898 physicians who lived and mainly worked in Sweden in October 2008 [24]. Statistics Sweden had information about the study population from the company Cegedim, including age, sex, and type of board specialist qualifications (after at least five years of resident training) – the latter provided by the National Board of Health and Welfare.

The response rate was 60.6% and of the physicians who answered the questionnaire, the 2701 who fulfilled the following criteria were included in the present investigation (see Table I): employed as a specialist in general practice (board certified GP), mainly worked in primary health care (PHC), and was below the age of 65 years. The more detailed analyses in the current study included the 2516 GPs (45% women) who had consultations involving sickness certification at least once a week. The overall response rate for GPs was 59.9%. Responses to items about the following aspects were analysed: the frequency and severity of problems regarding sickness certification and the frequency of issuing sick notes for unnecessarily long sick-leave periods, for different reasons. The specific items are presented in Table II and Figures 1 and 2.

Table I.

Total response rate among physicians with a specialty in general practice (GP), working in Sweden, aged less than 65 years, and working in primary health care (PHC) and frequency of sickness certification cases, respectively.1

| Study population All physicians in Sweden with a board speciality in general practice (GP) N |

Frequency of sickness-certification cases among the responding GPs working in PHC3 | |||||||||||||

| Responders | <65 years of age, and working in a PHC2 | At least 6 times per week | 1–5 times per week | A few times per month or year | Never or almost never | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % of resp. | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| All | 6900 | 41332 | 59.9 | 27012 | 65.4 | 1142 | 42.7 | 1374 | 51.4 | 121 | 4.5 | 38 | 1.4 | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Women | 2913 | 1820 | 62.5 | 1232 | 67.7 | 476 | 39.0 | 659 | 54.0 | 65 | 5.3 | 21 | 1.7 | |

| Men | 3987 | 2313 | 58.0 | 1469 | 63.5 | 666 | 45.8 | 715 | 49.2 | 56 | 3.9 | 17 | 1.2 | |

| Age | ||||||||||||||

| 32–54 year | 3028 | 1664 | 55.0 | 1281 | 77.0 | 581 | 45.6 | 637 | 50.0 | 45 | 3.5 | 10 | 0.8 | |

| 55–64 year | 3365 | 2134 | 63.4 | 1420 | 66.5 | 561 | 40.0 | 737 | 52.6 | 76 | 5.4 | 28 | 2.0 | |

| 65–92 year | 507 | 3352 | 66.1 | |||||||||||

Notes: 1The study group consisted of 2516 GPs who had such consultations at least once a week (figures given in bold).

2The difference between 4133 responding GPs and 2701 is due to the fact that 335 were above the age of 64 and that 1097 mainly worked in other typea of setting, e.g. occupational health service.

3Missing 26 (1.0%)

Table II.

Proportions of GPs (n = 2516) who experienced various situations related to handling sickness certification of patients.

| At least once a week | About once a month or a few times per year | Never or almost never | ||||

| How often in your clinical work do you… | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) |

| … find sickness certification cases to be problematic? | 54.5 | (52.6–56.5) | 43.8 | (41.9–45.8) | 1.7 | (1.1–2.2) |

| … encounter a patient who wants to be on sick leave for some reason other than work incapacity due to disease or injury? | 25.9 | (24.2–27.7) | 67.5 | (65.7–69.4) | 6.5 | (5.6–7.5) |

| … say no to a patient who asks for a sickness certificate? | 13.9 | (12.5–15.3) | 82.3 | (80.8–83.8) | 3.8 | (3.0–4.5) |

| … have a patient who, partly or completely, says no to a sick leave you suggest? | 6.8 | (5.8–7.8) | 68.0 | (66.2–69.9) | 25.2 | (23.4–26.9) |

| … issue a sickness certificate so that a patient will be eligible for higher benefit than unemployment or social security benefits? | 0.5 | (0.2–0.8) | 8.9 | (7.8–10.0) | 90.6 | (89.5–91.8) |

| … have conflicts with patients about sickness certification? | 11.3 | (10.0–12.5) | 74.6 | (72.9–76.3) | 14.1 | (12.8–15.5) |

| … worry that a patient will report you to the medical disciplinary board in connection with sickness certification? | 1.7 | (1.2–2.2) | 15.6 | (14.2–17.1) | 82.7 | (81.2–84.2) |

| … feel threatened by a patient in connection with sickness certification? | 1.4 | (0.9–1.8) | 21.3 | (19.7–22.9) | 77.3 | (75.7–79.0) |

| … worry that patients will go to another physician if you don't sickness certify? | 0.9 | (0.5–1.3) | 10.0 | (8.8–11.2) | 89.0 | (87.8–90.3) |

| … have patients saying they will change physician if you don't sickness certify? | 0.8 | (0.4–1.1) | 24.5 | (22.8–26.2) | 74.7 | (73.0–76.4) |

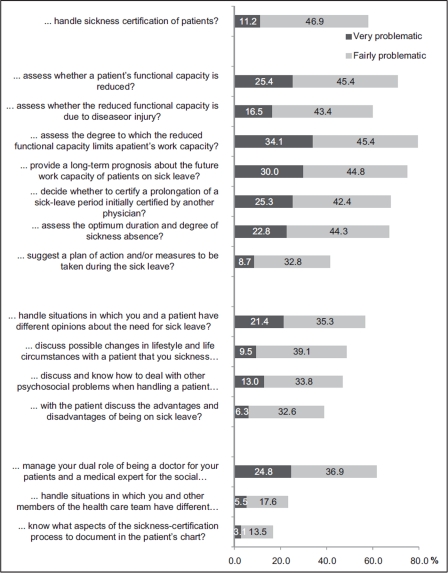

Figure 1.

Proportions of GPs (n = 2516) who rated different aspects of sickness certification as being very or fairly problematic.

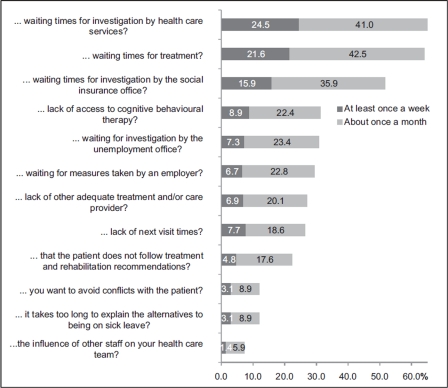

Figure 2.

Proportions of GPs (n = 2516) who, for different reasons and at least once a month, issued sick notes for unnecessarily long periods.

The response options were stated in terms of frequency or severity. Some were introduced with the phrase “How often in your clinical work do you….”, and the participant could choose between six answers ranging from “More than 10 times a week” to “Never or almost never”, which were categorized into three groups (Table II). The items relating to experienced severity of problems were phrased as “How problematic do you generally find it to …” followed by four response alternatives from “Very” to “Not at all” (see Figure 1). The third type of items began with “How often do you certify unnecessarily long sick leave periods due to …”, and the answers ranged from “Every day” to “Never or almost never” (see Figure 2). Descriptive statistics including estimation of p-values from Mann–Whitney tests were calculated.

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Stockholm (Reg. no. 2008/795-31).

Results

More than 90% (2516) of the 2701 GPs had consultations involving sickness certification at least once a week (see Table I), and these physicians were included in the analyses.

Problems related to sickness certification

In response to the general question about whether GPs found it problematic to handle sickness certification consultations, about half of the participants (54.5%) indicated that they had experienced this at least once a week (Table II). Considering specific aspects, about one-fourth (25.9%) of the GPs reported that at least once a week they had a patient who wanted a sickness certificate for some reason other than work incapacity due to disease or injury.

Regarding the severity of the reported problems, 58.1% indicated that handling sickness certification of patients was very or fairly problematic (Figure 1). Several of the issues that many of the GPs considered to be very problematic concerned assessments of functional or work capacity. Two other aspects that were rated as very or fairly problematic included handling situations in which the GP and the patient had different opinions about the need for sick leave (56.7%) and managing the two roles of being a physician for the patient and a medical expert for the SIO and other authorities (61.7%).

Certifying unnecessarily long sick leave periods

A majority of the GPs stated that they certified unnecessarily long sick leave periods at least once a month due to waiting times for investigations or medical treatments, but also because investigations at the SIO were pending (Figure 2). One-third (31.3%) did this due to lack of access to cognitive behavioural therapy for a patient. Furthermore, some (22.4%) certified unnecessarily long sick leave periods because the patient did not follow recommendations regarding treatment and rehabilitation, and 12.0% did so to avoid conflict with the patient or because it took too long to explain the alternatives to being on sick leave (11.9%). Regarding gender and age, there were some significant differences in responses to items relating to approving unnecessarily long sick leave periods (Table III).

Table III.

Proportions of GPs (n = 2516) who, for different reasons and at least once a month, issued sick notes for unnecessarily long periods by gender and age groups.1

| How often do you certify unnecessarily long sick-leave periods due to… | Women (n = 1135) | Men (n = 1381) | 32–54 years (n = 1218) | 55–64 years (n = 1298) |

| … waiting times for investigation by health care services? | 63.9 | 66.8* | 66.7 | 64.3 |

| … waiting times for treatment? | 61.5 | 66.3* | 63.5 | 64.7 |

| … waiting times for investigation by the social insurance office (SIO)? | 51.0 | 52.4 | 52.4 | 51.1 |

| … lack of access to cognitive behavioural therapy? | 34.0 | 29.1* | 34.1 | 28.5* |

| … waiting times for investigation by the unemployment office? | 31.6 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 31.5 |

| … waiting for measures to be taken by an employer? | 29.4 | 29.5 | 29.7 | 29.3 |

| … lack of other adequate treatment and/or care provider? | 28.6 | 25.9* | 28.0 | 26.2 |

| … lack of next visit times? | 26.7 | 26.0 | 27.8 | 24.9 |

| … that the patient does not follow recommendations for treatment and rehabilitation? | 23.0 | 21.9 | 26.1 | 18.8* |

| … you want to avoid conflicts with the patient? | 9.2 | 14.2* | 13.5 | 10.4* |

| … it takes too long to explain alternatives to being on sick leave? | 8.8 | 14.5* | 11.8 | 12.1 |

| … influence of other members of your healthcare team? | 7.3 | 7.3 | 8.4 | 6.3* |

Notes: 1Significant differences are shown in bold. *p < 0.05.

Discussion

This is, so far, the largest questionnaire study of GPs’ sickness certification practice. Sickness certification consultations were frequent, and a large proportion of the GPs found the tasks involved problematic. More specifically, a majority found it problematic to assess level of work incapacity and prognosticate on the duration of incapacity. Moreover, the GPs reported that they approved unnecessarily long sick leave periods for several different reasons.

The main strengths of this study are the large number of participants and the many and detailed questions concerning different aspects of sickness certification. Nevertheless, it is a limitation that 40% of the physicians who had specialized in general practice did not respond [24]. As in most questionnaire studies, the response rate was somewhat higher for women and older persons. As many GPs do not mainly work in PHC (see Table I), and also because we have no information on where the non-responders worked, more detailed analyses of those were not considered meaningful. As in all cross-sectional studies, no conclusion can be drawn regarding causalities. Another limitation is that we did not have information on the type of patients the physicians had. It is reasonable to assume that this differed with seniority and also influenced to what extent problems were experienced.

It is also possible that some GPs encounter problems that were not included in the survey. However, the questions were based on the results of previous studies based on questionnaires, and individual and focus-group interviews. Therefore, we believe that our findings represent good estimates of the type and severity of problems related to sickness certification in general practice.

Compared with the results of a previous Swedish questionnaire study of a considerably smaller population, our investigation confirmed that GPs experienced great problems in assessing work capacity [4,19]. Furthermore, our study showed that GPs find it difficult to handle conflicts with patients [2,4,5], although to a somewhat lesser extent than was noted in an investigation conducted four years previously [4]. This decrease might reflect several aspects, such as a number of interventions intended to inform the public about the sick leave rules and to support GPs in handling such cases, and a strong parallel decrease in sick leave rates in Sweden.

At least once a week, 3.1% wrote certificates for unnecessarily long sick leave periods to avoid conflicts with a patient. The GPs also reported several other reasons for certifying unnecessarily long sick leave, including different types of waiting times in health care and other organizations, most of which involved circumstances that the GPs had little influence over. However, some of these reasons were related to the consultation, such as the above-mentioned desire to avoid conflict with the patient, and more men than women stated this. Overall, the results from other studies go in different directions, regarding the influence of GPs’ age or sex on their sickness certification practices [8,15,18]. However, regarding consultation skills, there are findings indicating that female GPs practice more patient-centred consultations than their male colleagues do [25]. Such skills might include the capability to handle conflicts and possibly also that of taking time to discuss with the patient alternatives to being on sick leave.

In a recent systematic review of studies concerning GPs sickness certification, Wynne-Jones et al. [7], using a narrative approach, identified three major themes: conflict, role responsibility, and barriers to good practice. Conflict predominantly concerned contradictions between the GP and the patient, although there were cases that also involved other stakeholders. Both those aspects of conflict agree with our findings regarding reasons for granting unnecessarily long sick-leave periods. It is essential to consider the potentially negative consequences of such unnecessary sickness absence including the high cost to society and possible adverse effects that being on sick leave might have on individual patients [26–28].

Quite a few GPs reported certifying unnecessarily long sick-leave periods because the patient did not follow recommendations for treatment or rehabilitation. A smaller study, using a critical incidence technique, also found this [20]. It is a legal issue as to whether a patient who is not following such recommendations in the long run is actually entitled to sickness benefits.

To what extent the current results can be generalized to other countries is a matter of discussion, since there are international differences in health care and sickness insurance systems. Nevertheless, previous studies of GPs’ sickness certification practice conducted in different countries and during different time periods have provided surprisingly similar findings [3,6,29], and thus we believe that our results can provide a good basis for interventions regarding what might be done to support GPs in handling sickness certification. Education in terms of different aspects of assessing work capacity is one such intervention. Furthermore, guidance in consultation skills is urgent, particularly regarding handling of conflicts.

Conclusions

The GPs in this study experienced frequent and often severe problems in their sickness certification tasks. One major difficulty involved assessment of work incapacity per se and the duration of such incapacity. Another problem related to the professional role of physicians concerned being able to handle both the expectations of the patients and the conflicts that arise. The present results have implications for specialist training, for continuing medical education, and for management of primary health care. In a wider sense it is obvious that the possibilities to develop, maintain, and practise optimal professionalism regarding sickness certification are still lacking.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Acknowledgement

This study was financially supported by AFA Insurance and the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research.

References

- 1.Löfgren A. Physicians sickness certification practices: Frequency, problems, and learning. PhD Thesis, Stockholm: Karolinska Institutet; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wahlström R, Alexanderson K. Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU). Chapter 11. Physicians’ sick-listing practices. Scand J Public Health Suppl. 2004;63:222–55. doi: 10.1080/14034950410021916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexanderson K, Norlund A. Sickness absence: Causes, consequences, and physicians’ sickness certification practice. A systematic literature review by the Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care. Scand J Public Health. 2004;32((Suppl 63)):1–263. doi: 10.1080/14034950410003826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Löfgren A, Arrelöv B, Hagberg J, Ponzer S, Alexanderson K. Frequency and nature of problems associated with sickness certification tasks: a cross sectional questionnaire study of 5455 physicians. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2007;25:178–85. doi: 10.1080/02813430701430854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swartling MS, Hagberg J, Alexanderson K, Wahlström RA. Sick-listing as a psychosocial work problem: A survey of 3997 Swedish physicians. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17:398–408. doi: 10.1007/s10926-007-9090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussey S, Hoddinott P, Wilson P, Dowell J, Barbour R. Sickness certification system in the United Kingdom: Qualitative study of views of general practitioners in Scotland. Bmj. 2004;10:328:88. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37949.656389.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wynne-Jones G, Mallen CD, Main CJ, Dunn KM. What do GPs feel about sickness certification? A systematic search and narrative review. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2010;28:67–75. doi: 10.3109/02813431003696189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Söderberg E, Lindholm C, Kärrholm J, Alexanderson K. A systematic review] (in Swedish) Sweden: Ministry of Health and Welfare, SOU; 2010. Läkares sjuksrivningspraxis En systematisk litteraturöversikt [Physicians’ sickness certification practice. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swartling MS, Alexanderson KA, Wahlström RA. Barriers to good sickness certification: An interview study with Swedish general practitioners. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36:408–14. doi: 10.1177/1403494808090903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krohne K, Brage S. New rules meet established sickness certification practice: A focus-group study on the introduction of functional assessments in Norwegian primary care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2007;25:172–7. doi: 10.1080/02813430701267421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roope R, Parker G, Turner S. General practitioners’ use of sickness certificates. Occup Med. 2009;59:580–5. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wynne-Jones G, Mallen CD, Welsh V, Dunn KM. Rates of sickness certification in European primary care: A systematic review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2009;19:1–10. doi: 10.1080/13814780802687521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Knorring M, Sundberg L, Löfgren A, Alexanderson K. Problems in sickness certification of patients: A qualitative study on views of 26 physicians in Sweden. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2008;26:22–8. doi: 10.1080/02813430701747695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen DA, Aylward M, Rollnick S. Inside the fitness for work consultation: A qualitative study. Occup Med. 2009;59:347–52. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Englund L, Tibblin G, Svardsudd K. Variations in sick-listing practice among male and female physicians of different specialities based on case vignettes. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2000;18:48–52. doi: 10.1080/02813430050202569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Englund L, Svärdsudd K. Sick-listing habits among general practitioners in a Swedish county. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2000;18:81–6. doi: 10.1080/028134300750018954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Löfvander M, Engström A. An observer–participant study in primary care of assessments of inability to work in immigrant patients with ongoing sick leave. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2003:1–6. doi: 10.1080/02813430310002049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norrmén G, Svärdsudd K, Andersson D. Impact of physician-related factors on sickness certification in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2006;24:104–9. doi: 10.1080/02813430500525433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arrelöv B, Alexanderson K, Hagberg J, Löfgren A, Nilsson G, Ponzer S. Dealing with sickness certification: A survey of problems and strategies among general practitioners and orthopaedic surgeons. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:273. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timpka T, Hensing G, Alexanderson K. Dilemmas in sickness certification among Swedish physicians. Eur J Public Health. 1995;5:215–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engblom M, Alexanderson K, Englund L, Norrmén G, Rudebeck CE. When physicians get stuck in sick-listing consultations: A qualitative study of categories of sick-listing dilemmas. Work. 2010;35:137–42. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2010-0965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerner U, Alexanderson K. Issuing sickness certificates: A delicate task for physicians. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37:57–63. doi: 10.1177/1403494808097170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen J, Cohen D. Attitudes to work and health in doctors in training. Occup Med. 2010;60:640–4. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqq147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindholm C, Arrelöv B, Nilsson G, Löfgren A, Hinas E, Skånér Y, et al. Sickness-certification practice in different clinical settings: A survey of all physicians in a country. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:752. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roter DL, Hall JA. Physician gender and patient-centered communication: A critical review of empirical research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:497–519. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vahtera J, Pentti J, Kivimäki M. Sickness absence as a predictor of mortality among male and female employees. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:321–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.011817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staland Nyman C, Andersson L, Spak F, Hensing G. Exploring consequences of sickness absence: A longitudinal study on changes in self-rated physical health. Work. 2009;34:315–24. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2009-0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vingård E, Alexanderson K, Norlund A. Consequences of being on sick leave. Alexanderson K, Norlund A. Sickness absence: Causes, consequences, and physicians’ sickness certification practice. A systematic literature review by the Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care: Scand J Public Health. 2004:207–15. doi: 10.1080/14034950410021899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pransky G, Katz JN, Benjamin K, Himmelstein J. Improving the physician role in evaluating work ability and managing disability: A survey of primary care practitioners. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24:867–74. doi: 10.1080/09638280210142176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]