To the Editor: Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) is a feed-borne prion disease that affects mainly cattle but also other ruminants, felids, and humans (1). Currently, 3 types of BSE have been distinguished by Western immunoblot on the basis of the signature of the proteinase K–resistant fragment of the pathologic prion protein (PrPres): the classic type of BSE (C-BSE) and 2 so-called atypical types of BSE with higher or lower molecular masses of PrPres (H-BSE and L-BSE, respectively) (2). C-BSE is transmitted to cattle by ingestion of contaminated meat-and-bone meal, a feed supplement produced from animal carcasses and by-products. H-BSE and L-BSE have been identified by active disease surveillance, and incidence in aged cattle is low; but little is known about their epidemiology, pathobiology, and zoonotic potential (3). We describe 2 recent cases of BSE in aged cattle in Switzerland in which a PrPres phenotype distinct from those of C-, L- and H-BSE was unexpectedly displayed.

In April 2011, an 8-year-old cow (cow 1) died of accidental injury, with no apparent precedent clinical signs, on a farm in the canton of St. Gallen, Switzerland. In the context of active surveillance for BSE, the medulla oblongata was tested and found to be BSE positive by using the PrioStrip test (Prionics AG, Schlieren, Switzerland), a lateral-flow immunochromatographic assay for detection of PrPres. One month later, another cow (cow 2), 15 years of age, in the canton of Berne, Switzerland, was slaughtered because of a hind limb fracture. Information on this animal’s health status before death was unavailable. Statutory testing of the medulla oblongata gave a BSE-positive result by using the Prionics Check Western, a rapid Western blot technique (4). Medulla oblongata samples from the 2 animals were forwarded to the National Reference Laboratory for confirmatory testing.

In accordance with the guidelines of the World Organisation for Animal Health (5), BSE was confirmed for each animal by positive test results in independent, approved screening tests, of which 1 must be a Western blot (Technical Appendix). Because the tissues were severely autolyzed, target structures for the diagnosis of BSE could not be identified, and histopathologic and immunohistochemical results were inconclusive.

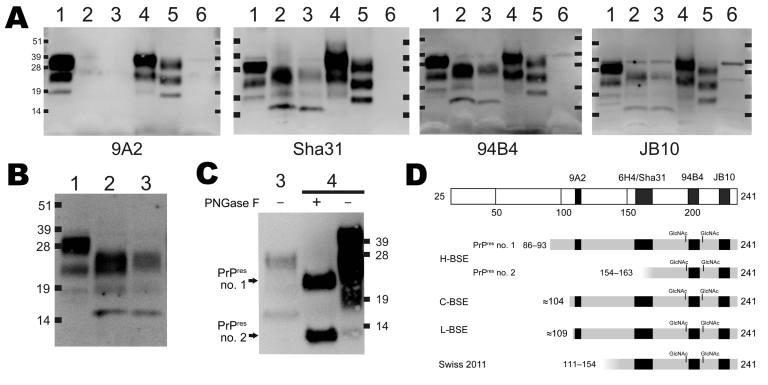

The Prionics Western blot detected a similar 3-band PrPres glycoprofile with molecular masses of roughly 16, 20, and 25 kDa for each animal, lower than equivalent PrP protein bands detected in animals with C-BSE (Figure). Sequencing of the open reading frame of the PRNP gene of cow 2 (which was unsuccessful for cow 1) indicated that the encoded protein was identical to the common bovine PrP amino acid sequence (as translated from GenBank accession no. AJ298878) and therefore was not likely to account for the differences observed by Western blot testing.

Figure.

Molecular typing of the pathologic prion protein from 2 cows with bovine spongiform encepalopathy (BSE), Switzerland. Brain tissue homogenates of medulla oblongata from cows 1 and 2 and from controls with C-BSE (Switzerland), H-BSE, and L-BSE (Poland [2]), and a BSE-negative sample were treated with proteinase K, subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and blotted onto membranes according to the protocol of the Prionics AG (Schlieren, Switzerland) Check Western test. On the basis of the antibody binding results, the N terminus of the PrPres fragment in the samples from cows 1 and 2 lies between aa 111 and aa 154. Predicted PrPres fragments of C-BSE, H-BSE (PrPres 1 and 2), and L-BSE were adopted from the literature (2,6). A) Epitope mapping using antibodies 9A2, Sha31, 94B4, and JB10. B) Confirmatory Western blotting using antibody 6H4. C) Comparison PrPres in cow 2 and H-BSE with (+) and without (–) deglycosylation with PNGaseF (antibody 94B4, SDS-PAGE with NuPAGE MES instead of NuPAGE MOPS running buffer [Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA]). PrPres 1 and 2 in H-BSE samples are indicated. Molecular mass standards are shown in kiloDaltons. D) The illustration at the top represents the full-length, mature bovine prion protein and the binding sites of the antibodies used for epitope mapping (black boxes). N-terminal and C-terminal residues are indicated by numbers. PrPres fragments are partially mono- and di-glycosylated, which results in the characteristic 3-band patterns in the Western immunoblot. Sites of N-linked glycosylation are shown at positions 192 and 208 (-GlcNAc). C-BSE, classic BSE; cow 1, an 8-year-old BSE-positive cow; cow 2, a 15-year-old BSE-positive cow; PrPres, proteinase K–resistant fragment of the prion protein; H-BSE, atypical BSE with higher molecular mass of PrPres; L-BSE, atypical BSE with lower molecular mass of PrPres. Lane 1, C-BSE; lane 2, cow 1; lane 3, cow 2; lane 4, H-BSE; lane 5, L-BSE; lane 6, negative.

We next investigated which region of the prion protein was present in these abberant PrPres fragments by probing with a panel of antibodies in the Western blot that bind to different regions of the prion protein (Technical Appendix). PrPres in cows 1 and 2 was readily detected by antibodies Sha31, 94B4, and JB10. By contrast, antibody 9A2, which maps to the PrPres N terminus, bound only to PrPres in samples from animals with C-, L- and H- BSE but not in samples from cows 1 and 2. The molecular masses of the PrPres moieties from the 2 cows were also clearly distinct from those from controls with L- and H-BSE (Figure). For samples from animals with H-BSE, enzymatic deglycosylation demonstrated PrPres subtypes, 1 and 2, the latter being a C-terminal PrPres fragment of ≈12–14 kDa (6). To investigate whether the novel PrPres type corresponds to PrPres subtype 2, we compared samples from cow 2 with those from the H-BSE control by Western blot. The PrPres type from the 2 cows reported here and PrPres subtype 2 from the H-BSE control were indeed distinct (Figure).

We report a novel PrPres signature in 2 cows with BSE diagnoses determined according to established criteria. Combining Western blot analysis with an epitope mapping strategy, we ascertained that these animals displayed an N terminally truncated PrPres different from currently classified BSE prions (Figure). The interpretation of these findings remains difficult because neuropathologic and systematic clinical data for the 2 cases are not available. Moreover, the tissue samples were autolyzed, and the question of whether this affected the PrPres molecular signature is of concern. Nonetheless, our findings raise the possibility that these cattle were affected by a prion disease not previously encountered and distinct from the known types of BSE. To confirm this possibility and to assess a potential effect on disease control and public health, in vivo transmission studies using transgenic mouse models and cattle are ongoing. Until results of these studies are available, molecular diagnostic techniques should be used so that such cases are not missed.

Supplementary Material

Details of 2 cows with bovine spongiform encephalopathy, Switzerland, 2011.

Acknowledgments

We thank the BSE screening laboratories at the Center of Laboratory Medicine (ZLM, St. Gallen, Switzerland), Prionics AG, and the veterinary services of the cantons of St. Gallen and Berne for their support. We also thank Jan P.M. Langeveld for kindly providing antibodies 9A2 and 94B4.

This work was financed with resources provided by the Swiss Federal Veterinary Office.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Seuberlich T, Gsponer M, Drögemüller C, Polak MP, McCutcheon S, Heim D, et al. Novel prion protein in BSE-affected cattle, Switzerland. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2012 Jan [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1801.111225

References

- 1.Colby DW, Prusiner SB. Prions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a006833. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs JG, Langeveld JP, Biacabe AG, Acutis PL, Polak MP, Gavier-Widen D, et al. Molecular discrimination of atypical bovine spongiform encephalopathy strains from a geographical region spanning a wide area in Europe. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1821–9. 10.1128/JCM.00160-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seuberlich T, Heim D, Zurbriggen A. Atypical transmissible spongiform encephalopathies in ruminants: a challenge for disease surveillance and control. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2010;22:823–42. 10.1177/104063871002200601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaller O, Fatzer R, Stack M, Clark J, Cooley W, Biffiger K, et al. Validation of a Western immunoblotting procedure for bovine PrP(Sc) detection and its use as a rapid surveillance method for the diagnosis of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). Acta Neuropathol. 1999;98:437–43. 10.1007/s004010051106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office Internationale des Epizooties. OIE rules for the official confirmation of BSE in bovines (based on an initial reactive result in an approved rapid test) by using a second rapid test. 2009. [cited 2011 Oct 19]. http://vla.defra.gov.uk/science/docs/sci_tse_oie_bse.pdf

- 6.Biacabe AG, Jacobs JG, Bencsik A, Langeveld JP, Baron TG. H-type bovine spongiform encephalopathy: complex molecular features and similarities with human prion diseases. Prion. 2007;1:61–8. 10.4161/pri.1.1.3828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Details of 2 cows with bovine spongiform encephalopathy, Switzerland, 2011.