Abstract

Differences between child welfare– and non-child welfare–involved families regarding barriers to child mental health care, attendance, program satisfaction, and relationship with facilitators are examined for a multiple family group service delivery model aimed at reducing childhood disruptive behaviors. Although child welfare–involved caregivers reported more treatment barriers and less program satisfaction than non-child-welfare-involved families, no significant differences exist between groups on average total sessions attended and attendance rates over time.

Children who remain at home with their permanent caregivers following a child welfare investigation manifest disproportionately high rates of behavioral difficulties, yet few initiate or remain in mental health treatment (Administration for Children and Families [ACF], 2005; Burns, Phillips, Wagner, Barth, Kolko, & Campbell, 2004; Lau & Weisz, 2003). The multiple family group (MFG) service delivery model to reduce childhood disruptive behavior disorders (Franco, Dean-Assael, & McKay, 2008; Gopalan & Franco, 2009; McKay, Gonzales, Quintana, Kim, & Abdul-Adil, 1999; McKay, Gonzales, Stone, Ryland, & Kohner, 1995; McKay, Harrison, Gonzales, Kim, & Quintana, 2002; Stone, McKay, & Stoops, 1996) addresses many typical treatment barriers through an explicit focus on family engagement, defined in this study by treatment attendance. This study presents preliminary data related to differences between child welfare–involved and non-child welfare–involved families regarding perceived barriers to MFG treatment participation, program satisfaction, relationship with facilitators, and attendance rates. Furthermore, this article discusses how the MFG model exemplifies engaging practices for child welfare–involved families, as well as how the model fits within the context of child and family rights.

Literature Review

Children involved with child welfare services frequently manifest elevated rates of emotional and behavioral difficulties (Burns et al., 2004; Costello, Angold, Burns, Stangl, Tweed, & Erkanli, 1996). While partly due to the deleterious effects of child maltreatment (English, 1998), child mental health difficulties are also likely to develop in response to stressors typically experienced by families involved in the child welfare system (e.g., poverty, domestic violence, parent substance abuse and mental illness, unstable housing; ACF, 2005; Crittenden, 1999; Fleck-Henderson, 2000; Littell & Tajima, 2000; Ondersma, 2002; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). However, only a minority of children who remain at home following a child welfare investigation and manifest clinical need actually receive mental health treatment (Leslie, Hurlburt, James, Landsverk, Slymen, & Zhang, 2005). This discrepancy between clinical need and receipt of care may be exacerbated by the lack of available service options within inner-city communities (Asen, 2002), as well as elevated rates of youth behavioral difficulties in low-income urban areas (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, Henry, & Florsheim, 2000).

Child welfare–involved families also typically suffer from multiple, co-occurring stressors, which hinder initial engagement and retention into treatment. Common barriers include lack of transportation and money, conflicts between work and mandated services, and child care difficulties (Kemp, Marcenko, Hoagwood, & Vesneski, 2009). Families are less likely to look for and be retained in child mental health treatment as parents may not have sufficient resources or motivation to seek help when extreme family problems are present (Harrison, McKay, & Bannon, 2004). Clients mandated to receive services may not self-identify as having difficulties, and, subsequently, manifest high rates of premature termination (Dawson & Berry, 2002; Rooney, 1992). Further, parents may avoid formal services due to prior unsatisfactory experiences with the child welfare system or conflictual relationships with service providers (Kerkorian, McKay, & Bannon, 2006; Palmer, Maiter, & Manji, 2006). Finally, stigma and negative perceptions about seeking care may cause ethnic minorities, who are disproportionately overrepresented in child welfare populations (ACF, 2005), to avoid traditional mental health services (Alvidrez, 1999; Snowden, 2001).

Consequently, families involved in the child welfare system are more likely to report a greater number of barriers to attending child mental health service appointments compared to non-child welfare–involved families. As prior research has linked fewer perceived treatment barriers to reduced risk of premature treatment termination (Kazdin, Holland, & Crowley, 1997; Kazdin, Holland, Crowley, & Breton, 1997), child welfare–involved families may experience particular difficulty engaging and maintaining treatment participation (Lau & Weisz, 2003; see also, Warner, Malinoskey-Rummell, Ellis, & Hansen, 1990, as cited in Hansen & Warner, 1994). Consequently, service models designed to overcome barriers to initial and ongoing service use are sorely needed.

The MFG service delivery model to reduce childhood disruptive behavior disorders has been specifically designed to address treatment barriers and promote positive service experiences for low-income, urban, minority families. Therefore, the MFG model may be particularly suited for engaging and retaining child welfare–involved families into care. Consequently, this study addresses the following research question: Among those offered MFGs, how do child welfare and non-child welfare–involved caregivers differ regarding (1) perceived barriers to treatment participation, (2) satisfaction with MFGs and relationships with group facilitators, and (3) MFG treatment attendance?

Methods

This study presents analyses of preliminary data from a larger effectiveness study that examines the impact of MFGs on families with children (aged 7–11 years old) meeting diagnostic criteria for oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. Between October 2006 and October 2010, families were recruited from 13 community child mental health clinics within a large, Northeastern urban area. In some families, more than one child was enrolled. Youth and family members were randomly assigned to either (1) MFG intervention group plus other clinical services deemed necessary by clinic providers (e.g., individual and/or family therapy, medication management) or (2) treatment as usual (e.g. individual and/or family therapy, medication management). Institutional review board approval was obtained.

Overview of MFG Service Delivery Model

This model has been previously described in Franco et al. (2008) and Gopalan and Franco (2009). Consisting of a series of weekly group meetings with six to eight families, the MFG model melds group therapy, family support, systemic family therapy, and behavioral parent training to target family factors consistently implicated in the onset and maintenance of childhood behavioral difficulties (e.g., discipline, parent-child relationships, family organization, parent-child communication). While most participants attended groups lasting 16 sessions, a subset (n = 45) received only 12 sessions due to requests to shorten the intervention by clinic providers. Developed in collaboration with urban, minority parent consumers of child mental health services, MFG curriculum content further addresses additional factors (i.e., effects of socioeconomic disadvantage, social isolation, high stress, lack of social support), which hinder effective parenting, contribute to childhood conduct difficulties, and influence early termination (Kazdin, 1995; Kazdin & Whitley, 2003; Wahler & Dumas, 1989).

Furthermore, the MFG model targets many of the logistical and perceptual barriers to accessing child mental health services by offering child care, transportation expenses, dinner, and a nonstigmatizing group setting, which normalizes family struggles. Frequent phone contact between sessions addresses any obstacles to participation, supports parenting skills, encourages homework completion, and reminds families to attend the next session. Finally, MFGs are co-facilitated by study site clinicians and at least one parent advocate with personal experiences navigating the child mental health system. In this way, the MFG model further promotes engagement and empowerment by capitalizing on the unique ability of parent advocates to build relationships with parents (Frame, Conley, & Berrick, 2006).

Over the course of the MFG implementation phase of the current study, program developed fidelity instruments were used to determine facilitator adherence to curriculum content in 15 out of 35 total MFG groups conducted (43%). Across all sessions, average fidelity rating is 94% (out of 100%).

Participants

This study focuses on n = 225 children enrolled in the experimental MFG group. Children residing in foster care at the initial assessment period (i.e., baseline) were excluded from the larger study. Families considered “child welfare–involved” included cases where caregivers indicated at baseline as having (1) a current or history of an open child welfare case, (2) ever had a child placed in foster care, (3) been referred and/or mandated by a child welfare organization to bring their child to counseling or other services, or (4) sought services to receive full custody or avert child removal from the home. Within the MFG experimental group, n = 84 children were identified as being child welfare–involved, while n = 141 children were identified has not having any child welfare involvement at baseline. Table 1 presents sample demographic characteristics at baseline. Except for employment status (χ2 = 13.25, p = .04), no other statistically significant differences were found between child welfare and non-child welfare–involved participants using chi-square tests for categorical variables (e.g., caregiver ethnicity) and independent t-tests for continuous variables (e.g., parent age). Participants in the MFG experimental group were largely low-income, black or Latino, and headed by single-parent, mother-only families. Few caregivers attained a post–high school education (n = 79, 35%), and close to one-third of caregivers (32%) reported being unemployed.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of MFG Experimental Group at Baseline (n = 225)

| Total | Child welfare involved (n = 84) | Non–child welfare involved (n = 141) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | %a | n | %b | n | %c |

| Caregiver ethnicity: | ||||||

| White/Caucasian | 21 | 9.33 | 7 | 8.33 | 14 | 9.93 |

| Black/African American | 63 | 28.00 | 30 | 35.71 | 33 | 23.40 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 119 | 52.89 | 40 | 47.62 | 79 | 56.03 |

| Native American | 2 | 0.89 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 1.42 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.44 | 1 | 1.19 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Other | 12 | 5.33 | 6 | 7.14 | 6 | 4.26 |

| Child ethnicity: | ||||||

| White/Caucasian | 16 | 7.11 | 8 | 9.52 | 8 | 5.67 |

| Black/African American | 66 | 29.33 | 29 | 34.52 | 37 | 26.24 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 112 | 49.78 | 36 | 42.86 | 76 | 53.90 |

| Native American | 3 | 1.33 | 1 | 1.19 | 2 | 1.42 |

| Other | 15 | 6.67 | 6 | 7.14 | 9 | 6.38 |

| Primary caregiver: | ||||||

| Mother | 175 | 77.78 | 66 | 78.57 | 109 | 77.30 |

| Father | 5 | 2.22 | 4 | 4.76 | 1 | 0.71 |

| Mother and father | 22 | 9.78 | 9 | 10.71 | 13 | 9.22 |

| Grandparent | 6 | 2.67 | 2 | 2.38 | 4 | 2.84 |

| Other | 9 | 4.00 | 3 | 3.57 | 6 | 4.26 |

| Caregiver marital status: | ||||||

| Single | 86 | 38.22 | 33 | 39.29 | 53 | 37.59 |

| Married or cohabiting | 81 | 36.00 | 27 | 32.14 | 54 | 38.30 |

| Divorced | 7 | 3.11 | 4 | 4.76 | 3 | 2.13 |

| Separated | 34 | 15.11 | 15 | 17.86 | 19 | 13.48 |

| Widowed | 4 | 1.78 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 2.84 |

| Other | 4 | 1.78 | 3 | 3.57 | 1 | 0.71 |

| Family income: | ||||||

| Less than $9,999 | 91 | 40.44 | 40 | 47.62 | 51 | 36.17 |

| $10,000 to $19,999 | 55 | 24.44 | 18 | 21.43 | 37 | 26.24 |

| $20,000 to $29,999 | 32 | 14.22 | 14 | 16.67 | 18 | 12.77 |

| $30,000 to $39,999 | 15 | 6.67 | 6 | 7.14 | 9 | 6.38 |

| $40,000 to $49,999 | 3 | 1.33 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 2.13 |

| Over $50,000 | 14 | 6.22 | 3 | 3.57 | 11 | 7.80 |

| Caregiver education status: | ||||||

| 8th grade or less | 27 | 12.00 | 5 | 5.95 | 22 | 15.60 |

| Some high school | 60 | 26.67 | 30 | 35.71 | 30 | 21.28 |

| Completed high school/GED | 51 | 22.67 | 17 | 20.24 | 34 | 24.11 |

| Some college | 49 | 21.78 | 17 | 20.24 | 32 | 22.70 |

| Completed college | 16 | 7.11 | 8 | 9.52 | 8 | 5.67 |

| Some graduate/professional school | 5 | 2.22 | 2 | 2.38 | 3 | 2.13 |

| Competed graduate/professional school | 9 | 4.00 | 5 | 5.95 | 4 | 2.84 |

| Caregiver employment status: | ||||||

| Employed full-time | 54 | 24.00 | 12 | 14.29 | 42 | 29.79 |

| Employed part-time | 40 | 17.78 | 13 | 15.48 | 27 | 19.15 |

| Student | 14 | 6.22 | 9 | 10.71 | 5 | 3.55 |

| Retired | 3 | 1.33 | 2 | 2.38 | 1 | 0.71 |

| Disabled | 26 | 11.56 | 12 | 14.29 | 14 | 9.93 |

| Unemployed | 71 | 31.56 | 30 | 35.71 | 41 | 29.08 |

| Other | 10 | 4.44 | 5 | 5.95 | 5 | 3.55 |

| Caregiver age (mean ± SD) | 35.73 ± 8.39 | 35.26 ± 7.82 | 36.02 ± 8.75 | |||

| Child age (mean ± SD) | 8.88 ± 1.45 | 8.76 ± 1.42 | 8.95 ± 1.47 | |||

Note: Numbers may not add up to n = 225 due to missing data.

% is out of experimental group sample size (n = 225)

% is out of child welfare involved group sample size (n = 84)

% is out of non-child welfare involved group sample size (n = 141)

Measures

Kazdin Barriers to Treatment Participation Scale

Kazdin Barriers to Treatment Participation Scale (KBT; Kazdin et al., 1997) is a 44-item, caregiver report measure of possible barriers to participation occurring over the course of treatment. At the posttest assessment (e.g., last session), caregivers indicated the extent to which various issues (e.g., “My child refused to come to session”) were a problem for each child involved in the study while participating in treatment, rated on a scale from 1 to 5 scale (ranging from never a problem to very often a problem). Higher scores indicate greater barriers to treatment participation. Scores ranged from 44 to 220. Cronbach alpha for this scale is 0.94.

Metropolitan Area Child Study Process Measures

Metropolitan Area Child Study process measures (MACS; Tolan, Hanish, McKay, & Dickey, 2002) is a caregiver-report instrument measuring treatment process completed at mid-test (8 weeks for 16 session intervention; 6 weeks for 12 session intervention) and posttest. This study used the treatment program satisfaction (TPS) and relationship with facilitator (RF) subscales. Caregivers indicated the extent to which various items (e.g., “I believe that group is helping my family”, “My facilitator has shown us respect”) were true while participating in treatment, rated on a scale from 1 to 4 (ranging from not at all to very much). Subscale scores range from 18 to 40 with higher scores indicating greater treatment satisfaction and more positive relationships with group facilitators. Cronbach alphas for both scales at mid- and posttest range from 0.88 to .95.

MFG Attendance

Throughout the MFG intervention, group facilitators indicated whether families attended each session (i.e., “Yes” or “No”). Percentage of sessions attended was computed for each quarter of the intervention period. For those participants who received the 16 session intervention, percent attendance for the first quarter corresponded to the percentage attended out of the first 4 sessions, while percent attendance for the second, third, and fourth quarter of the intervention corresponded to percent of sessions attended for sessions 5 to 8, 9 to 12, and 13 to 16, respectively. For the 12 session intervention, percent attendance by quarter corresponded to percentage of sessions attended for sessions 1 to 3, 4 to 6, 7 to 9, and 10 to 12, respectively. Finally, average total number of sessions attended for 12- and 16-session group participants was also computed.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics (e.g., mean, SD, Median) were computed for all measures. As preliminary analyses of the KBT and MACS subscales as well as average total number of sessions of attended were not normally distributed, nonparametric, Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney tests were used to evaluate differences on these measures between child welfare and non–child welfare MFG experimental group participants. Additionally, changes between mid- to posttest on MACS subscales were examined using Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests for matched pairs. These analyses used SPSS statistical software (Version 19).

Random coefficient modeling was performed on attendance rates over time using the SuperMix program for mixed effects regression models (Hedeker, Gibbons, Du Toit, Cheng, & Patterson, 2008). SuperMix uses maximum likelihood estimation to model measurements over time within cases. Within the final model, study participants were nested by the hierarchies of their individual ID, with time treated as a random effect. This form of modeling, also known as hierarchical linear modeling or multilevel linear modeling, allows parameters (intercepts and slopes) for measurements over time within cases to vary between cases, while accurately accounting for correlation between measurements within cases. It also allows for different times and numbers of measurements within people, an appropriate method to model longitudinal change involving data where there is attrition over time with the assumption that the missing data is ignorable (i.e., at least missing at random), which is a reasonable assumption with this data.

To test differences in percentage attendance between the child welfare versus non-child welfare group over time, a dichotomous variable for group was included in the full model predicting attendance rates. In addition, product terms for group were multiplied by time (i.e., first through fourth quarter) to test whether there were significant differences (interaction effect) between groups in attendance rates. Randomly varying intercepts were allowed in each model, which also enabled calculation of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), a measure of the percentage of variance between people compared to the total variance.

Findings

Barriers to Treatment, Program Satisfaction, and Relationship with Facilitators

Table 2 denotes that child welfare–involved caregivers reported a significantly greater number of barriers to treatment than non-child welfare–involved caregivers (U = 1957.50, Z = −3.05, p = 0.002, r = 0.24). Significant differences at posttest for the MACS TPS subscale (U = 2440.00, Z = −2.13, p = 0.03, r = 0.17) suggest that non-child welfare–involved caregivers reported greater median-level treatment program satisfaction at posttest than child welfare–involved caregivers. However, there were no significant differences by child welfare status for the MACS TPS scale at mid-test (U = 3181.50, Z = −0.48, p = 0.63, r = 0.04) as well as the MACS RF subscale at either mid- (U = 3244.50, Z = −0.18, p = 0.86, r = 0.01) or posttest (U = 2825.00, Z =−0.79, p = 0.43, r = 0.06).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Nonparametric Tests For KBT, MACS, and MFG Attendance

| Variable | Total (n = 225) | Child welfare–involved (n = 84) | Non-child welfare–involved (n = 141) | Significancea | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | Median | n | Mean (SD) | Median | n | Mean (SD) | Median | ||

| KBT scale at posttest | 157 | 60.02 (17.60) | 54 | 54 | 67.00 (21.80) | 58.5 | 103 | 56.36 (13.68) | 51 | ** |

| MACS TPS subscale Program satisfaction | ||||||||||

| Mid-test | 168 | 34.45 (4.88) | 36 | 64 | 34.19 (5.06) | 36 | 104 | 34.63 (4.78) | 36 | NS |

| Posttest | 165 | 35.17 (4.79) | 36 | 56 | 33.96 (5.35) | 35 | 109 | 35.80 (4.37) | 37 | * |

| MACS RF subscale Relationship with facilitator | ||||||||||

| Mid-test | 167 | 37.25 (4.09) | 40 | 64 | 37.06 (4.42) | 40 | 103 | 37.37 (3.89) | 40 | NS |

| Posttest | 165 | 37.65 (4.10) | 40 | 55 | 37.29 (4.43) | 40 | 110 | 37.84 (3.93) | 40 | NS |

| Attendance | 223 | 8.93 (4.91) | 10 | 83 | 8.53 (4.82) | 9 | 140 | 9.17 (4.97) | 10 | NS |

| 12 sessions | 45 | 8.18 (4.02) | 10 | 16 | 7.81 (4.13) | 9 | 29 | 8.38 (4.01) | 10 | NS |

| 16 sessions | 178 | 9.12 (5.10) | 10 | 67 | 8.70 (4.98) | 10 | 111 | 9.38 (5.18) | 10 | NS |

Note: Numbers may not add up to n = 225 due to missing data.

p < 0.01; NS: not significant (p < 0.05)

Mann-Whitney tests comparing differences between child welfare and non–child welfare groups.

Attendance

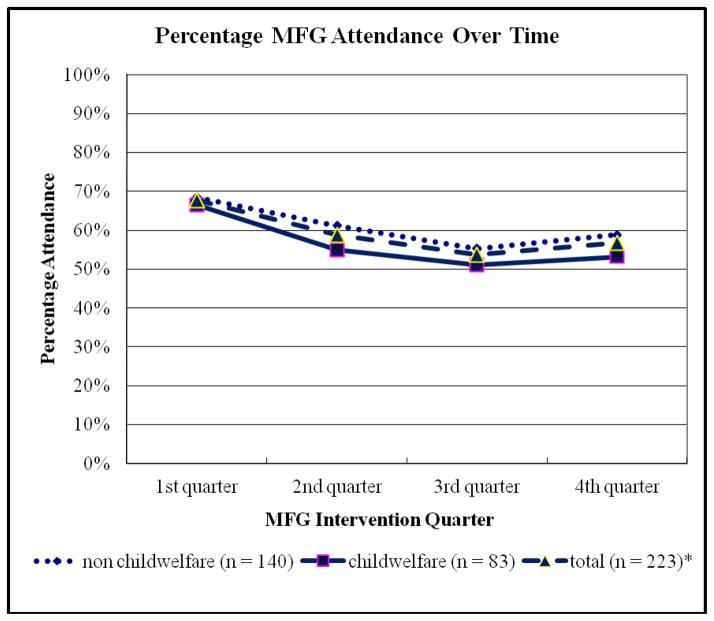

Figure 1 demonstrates rates of attendance over time for the total MFG experimental sample, child welfare, and non-child welfare–involved participants.

Figure 1.

* Note: Numbers do not add to n = 225 due to missing data

Finally, Table 2 indicates that all MFG participants attended an average of 8 to 9 sessions, whether they received the 12- versus the 16-session intervention. On average, number of sessions attended is slightly less for child welfare versus non-child welfare–involved participants for both the 12- and 16-session intervention. Yet, these differences are not statistically significant for those attending either the 12-session (U = 204.00, Z = −0.67, p = 0.50, r = 0.10) or the 16-session (U = 3381.00, Z = −1.02, p = 0.31, r = 0.08) intervention.

Table 3 presents results from the multivariate analyses, which indicate decreasing rates of attendance over time for all MFG experimental group participants (β = −0.04, SE = 0.01, Z = −3.68, p < 0.01). However, both the main effect for child welfare status (β = −0.03, SE = 0.05, Z = −0.51, p = 0.61) and the interaction of child welfare status by quarter (β = −0.01, SE = 0.02, Z = −0.45, p = 0.65) indicate there is no statistically significant difference in MFG attendance rates between child welfare–involved and non-child welfare–involved participants over time.

Table 3.

Multivariate Analyses Comparing MFG Attendance Over Time by Child Welfare Status

| Variable | β | SE | Z | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.70 | 0.03 | 23.20 | 0.00 ** |

| Child welfarea | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.51 | 0.61 |

| Quarter | −0.04 | 0.01 | −3.68 | 0.00 ** |

| Child welfare × quarter | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.45 | 0.65 |

p < 0.01

Child welfare status indicator: 0 = non-child welfare–involved, 1 = child welfare–involved

Discussion

This study compared child welfare and non-child-welfare-involved participants regarding perceived number of barriers to treatment, treatment process specific to program satisfaction and relationship with group facilitators, average number of MFG treatment sessions attended, and attendance rates over time. Findings indicate that child welfare–involved caregivers perceived a greater number of barriers to participating in the MFG intervention compared to non-child welfare–involved caregivers. Such findings are consistent with previous research indicating that child welfare–involved families suffer from multiple psychosocial stressors that increase the risk of child welfare–involvement as well as threaten engagement into services (Kemp et al., 2009; Littell & Tajima, 2000). Given these additional stressors, it is also possible that the needs of child welfare–involved families may not be as adequately addressed in the current MFG program as they might be for non–child welfare families, resulting in the significant differences in overall program satisfaction at posttest. Consequently, one would expect that child welfare–involved families would have significantly reduced MFG treatment attendance rates compared to non-child welfare–involved families.

However, although total average number of sessions attended and attendance rates over time for child welfare–involved families were slightly lower than those rates for non-child welfare–involved families, these differences were not statistically different. In combination, these findings suggest the differences in attendance between child welfare and non-child welfare–involved families are minimal. In contrast, Lau and Weisz (2003) found that child protective services–involved families were three times more likely (p < 0.01) than nonmaltreating families to terminate treatment prior to eight sessions.

Moreover, overall attendance rates for all groups exceed those normally seen in urban, inner-city child mental health clinics, where families generally attend only the first three to four sessions (McKay et al., 2002). McKay, Lynn, and Bannon (2005) reported that only 9% of children remained in treatment at the end of 12 weeks of treatment in urban inner-city clinics. However, as seen in this study, MFG participants attend at least an average of eight sessions regardless of child welfare status or length of the MFG intervention. Additionally, both child welfare–involved and non-child welfare–involved participants attend at least 50% of sessions by week 12 to week 16 of treatment.

This evidence of high treatment attendance in spite of greater treatment barriers and lower program satisfaction for child welfare families may be attributed to promising engagement practices highlighted in the child welfare literature that are used within the MFG model (Dawson & Berry, 2002; Kemp et al., 2009). For instance, frequent phone contact helps to engage families experiencing numerous stressors that potentially hinder treatment participation, as well as identify further service and referral needs. Providing funds to reimburse transportation costs, as well as offer child care and dinner at each session helps to retain families in groups by addressing some of the most common logistical barriers to participation (McKay & Bannon, 2004; Kemp et al., 2009). Similar to family group conferencing, MFG encourages the attendance of all family members to promote strength-based, participatory decision-making within families. Participants also benefit from opportunities to enhance skill-based learning and support between families. Within a destigmatizing group format, families are encouraged to develop an informal social support network with each other.

Finally, parent advocates as group facilitators represent an emerging strategy to promote family engagement, empowerment, as well as child and family rights. Their personal experiences as consumers of service systems provide parent advocates a unique perspective and knowledge base which professionals are unable to offer. As result, parent advocates can mentor caregivers in order to increase engagement and overall trust, as well as share their personal knowledge of navigating through community resources and complex service systems (Cohen & Canan, 2006; Rosenblum & Wulczyn, 2010). Moreover, parent advocates empower other caregivers with the hope that they, too, can resolve their families’ problems. Child and family rights are emphasized as families are provided with multiple sources of support and information to obtain all needed services. Additionally, caregivers’ rights to autonomy (Schoeman, 1980) are supported as parent advocates provide important information about the child mental health system. In this way, caregivers are allowed to make informed decisions about the types of services their family receives.

Limitations

However, the lack of significant findings related to relationship with program facilitators limits conclusions about the effect of parent advocates. The MACS relationship with facilitator process measures also did not differentiate between the different MFG facilitators present at each group. Since up to three facilitators (including parent advocates) could be present, one cannot disentangle caregivers’ experience for each individual facilitator. It should be acknowledged that other measures beyond attendance, such as homework completion rates, are also important in determining treatment adherence. However, at this time, final data on homework completion were not available within this preliminary dataset. Consequently, findings from the present study are limited by the sole reliance on attendance data. A fuller picture of treatment engagement would ideally gather information accounting for behavioral (e.g., treatment attendance, homework completion, demonstration of progress towards goals,) and attitudinal (e.g., emotional investment, commitment to treatment) components of engagement (Gopalan, Goldstein, Klingenstein, Sicher, & McKay, 2010).

Other limitations for this study include a relatively small sample size, which can reduce statistical power and ability for generalization. Given that analyses examining the differences between child welfare and non-child welfare–involved families for MFG treatment attendance did not find significant results, it is possible that the existing sample did not provide sufficient power. As the larger study focuses solely on participants residing in a large, Northeastern urban area, findings may not generalize to other nonurban communities. Additionally, participants in the comparison condition (treatment as usual) participated in treatment of varying length and modalities. Consequently, this study was limited by lack of a comparison treatment of similar length, such that differences in treatment attendance could not be determined between comparison and experimental conditions. As a final limitation, the categorization of child welfare status for the present study is based solely on the adult caregivers report alone at baseline, which may be subject to response bias.

Implications and Recommendations

Nevertheless, findings from the present study have important implications for future research and practice. Despite greater number of treatment barriers and less program satisfaction, child welfare–involved families appear to attend the MFG program at the same level as non–child welfare families. A qualitative study is currently underway which will elucidate why child welfare families engage and continue with the MFG model. Moreover, further studies will examine the extent to which treatment outcomes differ by child welfare status. Future research may also benefit from using administrative data to identify child welfare status and differentiate by maltreatment subtype, as well as other measures to assess behavioral and attitudinal components of program adherence beyond treatment attendance.

In terms of recommendations for practice, the MFG model presents a useful application of group-based treatment services provided in a nonstigmatizing format. Moreover, using parent advocates as facilitators may promote family engagement and empowerment. In this way, the MFG model exemplifies an engaging intervention for families involved in the child welfare system, aspects of which could be easily integrated into existing family support services to advance the child welfare field.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by award numbers R01MH072649 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Salary support (only) for this study also came from NIMH (F32MH090614). The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH or the National Institutes of Health. Portions of this paper were presented as an oral presentation at the 24th Annual Children’s Mental Health Research and Policy Conference held March 20–23, 2011. The authors gratefully acknowledge support from Sue Marcus and Lauren Rotko.

Contributor Information

Geetha Gopalan, Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

William Bannon, Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Kara Dean-Assael, Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Ashley Fuss, Fordham University.

Lauren Gardner, Fordham University.

Brooke LaBarbera, New York University.

Mary McKay, Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

References

- Administration for Children and Families. CPS sample component wave 1 data analysis report. Washington, DC: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J. Ethnic variations in mental health attitudes and service use among low-income African American, Latina, and European American young women. Community Mental Health Journal. 1999;35(6):515–530. doi: 10.1023/a:1018759201290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asen E. Multiple family therapy: An overview. Journal of Family Therapy. 2002;24(1):3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Burns BJ, Phillips SD, Wagner H, Barth RP, Kolko DJ, Campbell Y. Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: A national survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(8):960–970. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127590.95585.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Canan L. Closer to home: Parent mentors in child welfare. Child Welfare: Journal of Policy, Practice, and Program. 2006;85(5):867–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns BJ, Stangl DK, Tweed DL, Erkanli A. The Great Smoky Mountains study of youth: Goals, designs, methods, and prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1129–1136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PM. Child neglect: Causes and contributors. In: Dubowitz H, editor. Neglected children: Research, practice, and policy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson K, Berry M. Engaging families in child welfare services: An evidence based approach to best practice. Child Welfare. 2002;81(2):293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ. The extent and consequences of child maltreatment. Future of Youth. 1998;8(1):39–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleck-Henderson A. Domestic violence in the child protection system: Seeing double. Children and Youth Services Review. 2000;22(5):333–354. [Google Scholar]

- Frame L, Conley A, Berrick JD. “The real work is what they do together”: Peer support and birth parent change. Families in Society. 2006;87(4):509. [Google Scholar]

- Franco LM, Dean-Assael KM, McKay MM. Multiple family groups to reduce youth behavioral difficulties. In: LeCroy CW, editor. Handbook of evidence-based treatment manuals for children and adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 546–590. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan G, Franco LM. Multiple family groups to reduce disruptive behaviors. In: Gitterman A, Salmon R, editors. Encyclopedia of social work with groups. New York: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan G, Goldstein L, Klingenstein K, Sicher C, McKay M. Engaging families into child mental health treatment: updates and special considerations. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;19(3):182–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry DB, Florsheim P. Patterns of family functioning and adolescent outcomes among urban African American and Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14(3):436–457. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DJ, Warner JE. Treatment adherence of maltreating families: A survey of professionals regarding prevalence and enhancement strategies. Journal of Family Violence. 1994;9(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison ME, McKay MM, Bannon WM., Jr Inner-city child mental health service use: The real question is why youth and families do not use services. Community Mental Health Journal. 2004;40(2):119–131. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000022732.80714.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD, Du Toit SH, Cheng, Patterson D. SuperMix: A program for mixed-effects regression models. Chicago: Scientific Software International; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Conduct disorders in childhood and adolescence. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Holland L, Crowley M. Family experience of barriers to treatment and premature termination from child therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:453–463. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Holland L, Crowley M, Breton S. Barriers to treatment participation scale: Evaluation and validation in the context of child outpatient treatment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:1051–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Whitley MK. Treatment of parental stress to enhance therapeutic change among children referred for aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(3):504–515. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp SP, Marcenko MO, Hoagwood K, Vesneski W. Engaging parents in child welfare services: Bridging family needs and child welfare mandates. Child Welfare. 2009;88(1):101–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkorian D, McKay M, Bannon WM., Jr Seeking help a second time: Parents’/caregivers’ characterizations of previous experiences with mental health services for their children and perceptions of barriers to future use. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(2):161–166. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, Weisz JR. Reported maltreatment among clinic-referred children: Implications for presenting problems, treatment attrition, and long-term outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(11):1327–1334. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000085754.71002.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie LK, Hurlburt MS, James S, Landsverk J, Slymen DJ, Zhang J. Relationship between entry into child welfare and mental health service use. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(8):981–987. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell JH, Tajima EA. A multilevel model of client participation in intensive family preservation services. Social Service Review. 2000;74(3):405–435. [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Bannon WM., Jr Engaging families in child mental health services. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2004;13:905–921. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Gonzales J, Quintana E, Kim L, Abdul-Adil J. Multiple family groups: An alternative for reducing disruptive behavioral difficulties of urban children. Research on Social Work Practice. 1999;9(5):593–607. [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Gonzales JJ, Stone S, Ryland D, Kohner K. Multiple family therapy groups: A responsive intervention model for inner city families. Social Work with Groups. 1995;18(4):41–56. [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Harrison ME, Gonzales J, Kim L, Quintana E. Multiple-family groups for urban children with conduct difficulties and their families. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(11):1467–1468. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.11.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Lynn CJ, Bannon WM. Understanding inner city child mental health need and trauma exposure: Implications for preparing urban service providers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75(2):201–210. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondersma SJ. Predictors of neglect within low-SES families: The importance of substance abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2002;73(3):383–391. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer S, Maiter S, Manji S. Effective intervention in child protective services: Learning from parents. Children and Youth Services Review. 2006;28(7):812–824. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney RH. Strategies to work with involuntary clients. New York: Columbia University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum R, Wulczyn F. The parent advocate initiative: Promoting parent advocates in foster care evaluation report. Chicago: Chapin Hall, University of Chicago; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeman F. Rights of children, rights of parents, and the moral basis of the family. Ethics. 1980;91:6–19. [Google Scholar]

- Snowden LR. Barriers to effective mental health services for African Americans. Mental Health Services Research. 2001;3:181–187. doi: 10.1023/a:1013172913880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone S, McKay MM, Stoops C. Evaluating multiple family groups to address the behavioral difficulties of urban children. Small Group Research. 1996;27(3):398–415. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Hanish L, McKay MM, Dickey MH. Evaluating process in child and family interventions: Aggression prevention as an example. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16(2):220–236. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wahler RG, Dumas JE. Attentional problems in dysfunctional mother-child interactions: An interbehavioral model. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;105:116–130. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.105.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]