Abstract

Objective

To assess the effects of a maintenance program (monthly newsletters versus monthly group classes and telephone behavioral sessions) on obesity and metabolic disease risk at one year in overweight minority adolescents.

Methods

After a 4-month nutrition and strength training intervention, 53 overweight Latino and African American adolescents (15.4 ±1.1 yrs) were randomized into one of two maintenance groups for 8 months: monthly newsletters (n=23) or group classes (n=30; monthly classes + individualized behavioral telephone sessions). The following outcomes were measured at months 4 (immediately following the intense intervention) and month 12: height, weight, blood pressure, body composition via BodPod™, lipids and glucose/insulin indices via frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test (FSIVGTT).

Results

There were no significant group by time interactions for any of the health outcomes. There were significant time effects in several outcomes for both groups from month 4 to 12: bench press and leg press decreased by 5% and 14% (p=0.004 & p=0.01), fasting insulin and acute insulin response decreased by 26% and 16% (p<0.001 & p=0.046); while HDL cholesterol and insulin sensitivity improved by 5% and 14% (p=0.042 and p=0.039).

Conclusions

Newsletters as opposed to group classes may suffice as follow-up maintenance programs to decrease type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk in overweight minority adolescents.

Keywords: Maintenance, Obesity Intervention, Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular risk factors, Latino and African American adolescents

INTRODUCTION

Los Angeles (LA) is one of the few cities in the US where foreign-born people constitute a majority, with 40–50% of the residents being of Latino descent (1). The prevalence of obesity in LA varies markedly by ethnic/racial group, with Latinos having among the highest rates (2), which puts them at elevated risk for associated chronic diseases. We have previously shown that Latino children who are overweight and living in LA have elevated levels of visceral adiposity and liver fat, are extremely insulin resistant, and exhibit early signs of beta-cell dysfunction and carotid thickness, all of which are linked to increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)(3–8).

To date, lifestyle interventions remain the most well-established and tested interventions for overweight youth and adolescents. However, there are few pediatric studies that support long-term efficacy(9, 10), and strategies for maintaining weight loss remains a challenge. In addition, few maintenance studies have been conducted to assess the effects on metabolic parameters in youth, and even fewer have been conducted with high-risk overweight Latino and African American adolescents. The majority of the existing long-term intervention studies are limited to changes in BMI or weight, and fasting blood values, at best (9, 11). To our knowledge, no studies have been conducted to assess the 1-year effects of an intervention on glucose and insulin action using more precise measures, such as the FSIVGTT. In addition, the majority of the existing studies often use a maintenance period consisting of monthly or bi-monthly booster sessions. Little is known about what mode of delivery of maintenance sessions is optimal to result in improved health outcomes.

The current intervention employed a modified carbohydrate dietary approach, focusing on reducing added sugar and increasing dietary fiber. Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses from our group consistently have shown that the quality of carbohydrate plays a major role in adiposity and metabolic disorders in Latino and African American youth(12–16). Specifically, our group has shown that high intakes of total and added sugar and sugary beverages were associated with adiposity and poor beta-cell function(12, 13), while high intakes of dietary fiber is consistently linked to reductions in visceral adiposity and metabolic syndrome(14, 15). Results from our 12-week nutrition pilot intervention with 30 overweight Latina adolescent females, which was focused on a modification of carbohydrates approach, showed that participants who decreased added sugar by as little as 5% per day had significant improvements in insulin secretion(17). Similarly, a 6-month reduced glycemic load diet as compared to an energy restricted, reduced-fat diet resulted in significant reductions in fat mass and insulin resistance as measured by homeostasis model assessment in primarily Caucasian obese adolescents(18). However, the long-term effects of a modified carbohydrate approach on metabolic parameters have not yet been tested.

The current intervention also used a strength training exercise approach. Research has shown that strength training reduces total and regional body composition, improves insulin sensitivity and HDL cholesterol(19, 20). Furthermore, strength training for overweight children may improve program retention(21). We have previously shown Hispanic adolescents who completed a 12-week strength training pilot intervention had a 45% improvement in insulin sensitivity compared to controls(22). To our knowledge, no intervention study has examined the effects at 1-year of a modified carbohydrate dietary approach combined with strength training on such metabolic risk factors.

The goals of the present study were: a) to evaluate the effects of an 8-month maintenance intervention, following the intense 4-month intervention, which was focused on modification of carbohydrates and strength training, on body composition, insulin action, and lipids at one year; and b) to assess what mode of delivery of the maintenance program (monthly newsletters versus monthly group classes and behavioral sessions) was more effective at improving these health outcomes. For this study, we hypothesized that the maintenance groups would have improvements in health outcomes at one year, but the more intense maintenance group (consisting of monthly group classes and telephone behavioral therapy sessions) would have greater improvements in health compared to the newsletter group.

REASEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

METHODS

The program specifics and the main outcome results of the 4-month intervention have been previously reported (23, 24). In brief, the goal of the 4-month modified carbohydrate nutrition and strength training intervention for Latino and African American adolescents was to assess the incremental effects on insulin indices, adiposity, and other metabolic risk factors for type 2 diabetes, of the following intervention groups: (1) control, (2) a once per week modified carbohydrate nutrition education program (N group), and (3) the same nutrition education program with twice per week strength training (N+ST group). Following the intervention, the N group had significant improvements in insulin sensitivity (SI) and disposition index (DI; a measure of beta-cell function), while the N+ST group had significant reductions in hepatic fat, when compared to the control group (24). The N+ST group had significant increases in upper and lower strength and the N and N+ST groups had significant reductions in energy intake, carbohydrate intake and added sugar intake compared to the control group (24). There were no significant effects on weight or total body composition.

Participants

Any participant who completed the initial 4-month intervention (summer of 2008) was eligible to participate in the maintenance study. Participants were recruited into the initial 4-month intervention from schools, community centers, and health clinics. The inclusion criteria for the initial 4-month intervention was: age- and gender-specific BMI ≥ 85th percentile (CDC, 2000), African American or Latino ethnicity, and grades 9th thru 12th. There were no additional inclusion criteria to be in the maintenance program. Prior to any testing procedure, informed written consent from parents and children were obtained. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern California (USC), Health Sciences Campus.

Testing at the Clinical Trials Unit (CTU)

The following measures were performed 1 week before the initial 4-month intervention began), month 4 (1 week after the initial 4-month intervention) and month 12 (1 week after the 8-month maintenance program) in the USC CTU.

Anthropometrics, Body Composition, and Blood Pressure

A detailed medical history and physical exam was performed, where Tanner staging was determined using established guidelines(25, 26). Weight and height were measured and BMI and BMI percentiles were then calculated(27). Total fat mass and lean tissue mass were measured by air displacement plethysmography (BodPod™; Life Measurement Instruments, Concord, CA). Blood pressure was obtained according to recommendations of the American Heart Association(28).

Glucose and Insulin Indices

After an overnight fast, an insulin-modified frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test (FSIVGTT)(29) was performed with minimal modeling to determine insulin sensitivity (SI), acute insulin response (AIR), disposition index (DI, an index of β-cell function), and glucose effectiveness (Sg).

Dietary Intake and Strength Assessment

Dietary intake was assessed by 3-day diet records, which are validated measures of dietary intake in child and adolescent populations (30, 31). Participants were given a short lesson (10 min) on how to estimate portion sizes and complete the diet records and were given measuring cups and rulers to aid in accurate reporting. At all in-patient visits, research staff clarified all dietary records. Nutrition data were analyzed using the Nutrition Data System for Research (NDS-R version 5.0_35). Using established procedures(32, 33), upper-and lower-body strength assessments were completed before and after the intervention by one-repetition maximum (1-RM) in the bench press and leg press, respectively.

Maintenance Randomization

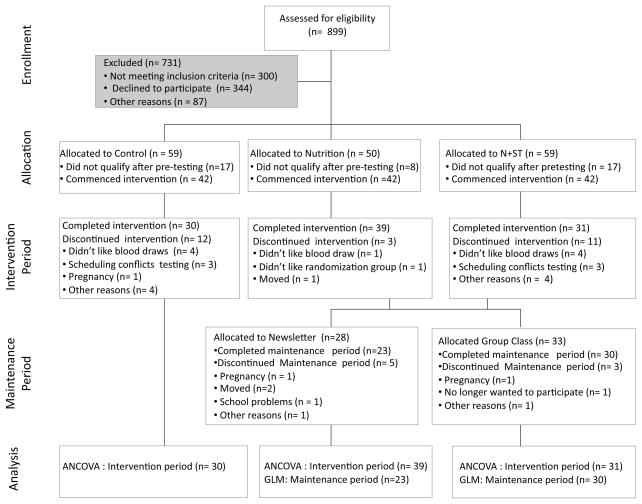

The CONSORT diagram of the maintenance intervention is shown in Figure 1. Of the 100 participants who completed the 4-month interventions, 30 of them were control participants and received the delayed intervention (abbreviated version of the N+ST intervention), and therefore were not eligible to participate in the maintenance program. Of the 70 participants who completed either the N or N+ST intervention, 9 were not interested in being a part of the maintenance study. Sixty-one participants were then randomized to either the newsletter group (n=28) or the group class (n=33). Of these 61 participants, only 53 remained in the maintenance program and completed post-testing at 12 months; 23 in the newsletter group and 30 in the group class. Randomization was conducted by a statistician independent from the study using computer generated random numbers, and allocations were concealed from participants until after they consented to be in the maintenance program. Randomization was blocked by initial intervention group, gender and ethnicity.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram of the initial 4-month intervention and the 8-month maintenance Intervention

Description of the Maintenance Intervention

Maintenance Newsletter Group

Participants in the newsletter group received a monthly newsletter in the mail that matched their 4-month intervention group assignment (i.e., either a nutrition specific newsletter or a nutrition + strength training newsletter). The newsletter covered basic tips on how to continue to eat foods and drink beverages low in sugar and high in fiber and included one or two new low-sugar or high fiber recipes. Benefits of strength training and sample strength training exercises were highlighted in the newsletters. In addition, a list of community resources (i.e., local recreational centers) was given to promote strength training. Specific nutrition topics, objectives, recipes, and ST exercises covered in the monthly newsletters are listed in Table 1. Research staff called participants twice during the maintenance intervention to make sure they were receiving the newsletters and that their contact information was still correct, however staff did not discuss any additional content, strategies, progress, or motivation related to the program with any participant during these calls. The main purpose for these calls was to make sure participant’s still had the same phone number and addresses, so that we could make sure they were available for post-testing. In the past, we have had a lot of issues with control participants moving away or changing their phone numbers and being unable to reach them for post-testing.

Table 1.

Maintenance Curriculum Topics

| Month | Nutrition Topic for Both Group Class and Newsletter | Key Objective | Sample Recipe | Highlighted Strength Training Exercise |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Life After | How to maintain the dietary changes achieved in the 16-week program, with a specific focus on eating a low sugar, high fiber diet. | Shrimp cocktail with vegetables | Benefits of strength training (ST) |

| 2 | Grocery shopping | How to select high fiber, low added sugar foods at the grocery store, particularly fresh fruits and vegetables and whole grains. | Whole wheat pita pizzas | Featured exercise: squats |

| 3 | School Food | How to pack healthy lunches and snacks with an emphasis on use of whole grain bread for sandwiches and use of a water bottle to avoid sugar-sweetened beverages. | Smoothies and sandwiches | Using resistance bands; Featured exercise: lunges |

| 4 | Fast Food | How to find healthier options on fast food menus, with an emphasis on selecting items such as salad and other foods that do not contain refined carbohydrates. An additional focus was how to make your own “fast food” at home. | Spring salad with grilled chicken | Making ST a part of daily life. |

| 5 | Fruits and Vegetables | How to find a farmer’s market and how to select and sample local, seasonal fruits and vegetables. | Snacks from the Farmer’s market | Available ST resources: local gyms/community clubs |

| 6 | Emotional Eating/Holiday Foods | How to avoid overdoing it around the holidays and how to make healthy, festive holiday foods that are low in sugar and high in fiber. | Baked yams and holiday snack/trail mix. | Core strength: Planks and abdominal crunches |

| 7 | Junk Food | How to find alternatives to favorite junk foods, such as finding other foods that satisfy the same cravings of spicy, sweet, or sour. | Fruit and yogurt parfaits | Featured upper body exercises with free weights: shoulder press |

| 8 | Party/Evaluations | How to create a healthy potluck dish. A review of all of the class topics was also given in the form of a trivia game. | Potluck | Maintaining motivation for ST; Featured exercise: tricep extensions with the resistance bands |

Maintenance Group Class

Participants in the group class met monthly (classes lasted 90 minutes) at the Veronica Atkins Lifestyle Intervention Laboratory (VALIL) and received a monthly class that was similar to their 4-month intervention classes (i.e., either N only or N+ST). They included a cooking component, a snack, a nutrition lesson (focused on reducing sugar and increasing fiber intake), and a 45-minute strength training session (for those subjects in the N+ST group), led by a certified personal trainer. A list of nutrition topics, key objectives, and recipes prepared at each of the classes is highlighted in Table 1. Although participants only met once per month and there were not specific tasks that participants were required to do, they were encouraged to eat healthy and do strength training on their own at home throughout the entire program. All participants received a variety of cooking utensils and gadgets (i.e., cutting boards, apple cutters, measuring cups, etc.) throughout the program. Participants in the N+ST group also received resistance bands and an instructional video of exercises to do with the bands. In addition, the trainers gave a list of resources (i.e., local gyms and/or community centers with exercise equipment) to all participants. All participants attended at least six of the eight monthly group sessions. Make-up classes were offered on three separate occasions. Twenty-four participants (or 80%) attended all eight classes, four participants (13%) attended seven classes and two participants (7%) attended six classes.

The intervention was based on Self-Determination Theory (34), and designed to increase motivation for healthy diet and exercise. Therefore, participants in the group class also received 4 motivational interviewing (MI) sessions, conducted over the phone and lasting approximately 15 minutes, throughout the 8-month program by trained research staff. MI is a client-centered counseling approach designed to enhance intrinsic motivation for behavior change by exploring and resolving ambivalence (17). It was hypothesized that by increasing intrinsic motivation a healthy lifestyle, program effects would sustain and become internalized, ensuring long-term benefit for participants. The sessions were designed to help participants resolve ambivalence and engage in healthier eating, specifically decreasing sugar and increasing fiber, and strength training on their own at home. All participants received four phone sessions, and on average the calls were 16 ±4 minutes.

Parent(s) were also offered separate monthly classes, which were held simultaneously at the VALIL. The curriculum was the same that their child was receiving. Bilingual instructors were used and all material was available and taught in Spanish if needed. Although parents were asked to attend a minimum of two classes, participation was very low, with 15% of the parents attending the minimum of two classes.

Statistical Procedures

Sample size

Sample size calculations were based on results from our strength training pilot study(22). Using a conservative estimate of the standard deviation of the insulin sensitivity change score, a sample size of 22 (11 per group) had a 0.80 power to detect a meaningful difference >0.57 units in mean change in insulin sensitivity between control and strength training group. Post-hoc power calculations were performed based on the between maintenance group mean differences (mean ±SD). The correlation among repeated measures ranged from 0.5 (for AIR) to 0.9 (for BMI z-scores). The effect sizes ranged from 0.3 (for AIR), 0.4 (for BMI and HDL), 0.5 (for SI), and 0.7 (for fasting insulin and bench press), with a total sample size of 53 or >20 in each group being sufficient to detect significance in most health outcomes.

Analyses

Data were examined for normality and the following outcome variables were not normally distributed and analyses were run on the log-transformed values: weight, lean mass, fasting insulin, SI, AIR, DI, and Sg. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustments and Chi-square test (for gender and ethnicity only) were employed to assess differences in physical and metabolic measures and dietary and strength variables at baseline (or month four for this analyses) between the two maintenance groups (i.e., newsletter vs. group class) and the four maintenance groups (i.e., nutrition newsletter vs. nutrition + ST newsletter vs. nutrition only group class vs. Nutrition + ST group class).

GLM repeated measures, with post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustments, were used to assess changes in all health outcomes (i.e., dietary intake, strength, body composition, glucose/insulin indices, and lipids) from baseline (or month four) to 1-year and between maintenance intervention groups (both the two and four maintenance groups). Covariates included the initial intervention assignment (either N or N+ST), ethnicity, age, gender, body composition (when glucose/insulin indices were dependent variables) and SI (when AIR was dependent variable). All analyses and randomization were performed using SPSS version 16.0, (SPSS, Chicago, IL), with significance level set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

There were no significant differences before the initial 4-month intervention in demographic, adiposity (including weight, BMI parameters and body composition), metabolic, dietary and strength variables between the 84 participants who completed the 4-month intense intervention and the 53 participants who completed the maintenance program. Nor were there any differences before initial 4-month intervention in demographic, adiposity, or metabolic, dietary and strength variables, between the 61 participants allocated to the maintenance program and the 53 who actually completed it.

We initially analyzed the differences between the 4 maintenance groups, and were originally powered to detect differences in changes in insulin resistance (our main outcome of interest) with as few as 11 in each intervention group. However, with attrition we ended up with 8 subjects in the nutrition only newsletter group. In addition the results (both intent-to-treat and over time) were identical when analyzing the data with either two or four maintenance groups. Therefore, given the identical results and the power issues, data is presented below between the two maintenance groups.

The 4-month physical and metabolic characteristics between the two maintenance groups are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences in any demographic, physical, or metabolic characteristics between the two maintenance groups at month four. The 4-month strength and dietary characteristics between maintenance groups (i.e., newsletter vs. group class) are shown in Table 3. Protein, expressed as a percent of calories per day, was significantly higher in the Newsletter group compared to the Group class at month four (18.9% vs. 16.2%; p=0.05). There were no other significant differences in any dietary and strength, variables between the two maintenance groups at month four.

Table 2.

Physical and metabolic characteristics of maintenance groups (n=53) at baseline (i.e., Month 4).

| Newsletter Group (n=23) | Group Class (n=30) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 15.8 (0.9) | 15.6 (1.1) | 0.50 |

| Sex (M/F) | 7/16 | 17/13 | 0.93 |

| Tanner | 4.7 (0.6) | 4.4 (0.9) | 0.31 |

| Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | |||

| Systolic | 116.5 (14.4) | 121.7 (11.3) | 0.15 |

| Diastolic | 63.4 (7.5) | 66.2 (8.0) | 0.25 |

| Body Composition | |||

| Weight (kg) | 97.1 (18.9) | 96.6 (24.6) | 0.93 |

| Height (cm) | 164.9 (8.5) | 166.5 (9.0) | 0.52 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.3 (6.1) | 34.6 (6.7) | 0.69 |

| BMI Z-score | 2.2 (0.5) | 2.2 (0.5) | 0.91 |

| BMI Percentile | 97.3 (4.0) | 97.6 (2.6) | 0.80 |

| Total Fat (kg) | 38.6 (17.6) | 38.3 (15.4) | 0.95 |

| Total Lean (kg) | 58.5 (8.9) | 58.3 (11.6) | 0.72 |

| Glucose/Insulin Indices | |||

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dl) | 88.6 (6.4) | 88.6 (6.8) | 0.98 |

| Fasting Insulin (μU/ml) | 24.4 (11.2) | 19.1 (9.5) | 0.10 |

| SI (X10−4 min−1/μU/ml) | 1.3 (1.0) | 1.4 (0.9) | 0.73 |

| AIR (μU/ml × 10 min) | 1916.3 (1078.7) | 2295.1 (2303.3) | 0.50 |

| DI (X10−4 min−1) | 2042.2 (1489.4) | 2122.2 (1280.5) | 0.84 |

| Glucose Effectiveness (Sg; % per min) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.67 |

| Lipids | |||

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 141.2 (24.5) | 146.0 (35.3) | 0.67 |

| Triglycerides (TAG; mg/dl) | 80.5 (33.8) | 91.4 (40.4) | 0.65 |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 88.4 (23.9) | 91.3 (29.9) | 0.33 |

| VLDL Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 16.1 (6.7) | 18.4 (8.0) | 0.72 |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 37.3 (8.2) | 36.4 (6.8) | 0.66 |

Data are mean (SD).

P-values were calculated using ANOVA. Analyses were based on log scores for the following variables: weight, total fat, total lean mass, fasting glucose and insulin, SI, AIR, DI, Sg, VLDL, HDL, and TAG.

Table 3.

Strength and dietary characteristics of maintenance groups (n=53) at baseline (i.e., Month 4) a

| Newsletter Group (n=23) | Group Class (n=30) | P-value b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strength | |||

| Bench Press (kg) | 107 (27) | 117 (40) | 0.32 |

| Leg Press (kg) | 519 (166) | 494 (164) | 0.60 |

| Dietary c | |||

| Energy (kJ/d) | 6670 (2738) | 7214 (2814) | 0.48 |

| Carbohydrate (g/d) | 192 (79) | 222 (81) | 0.19 |

| Carbohydrate (% kcals) | 48 (9) | 52 (8) | 0.07 |

| Protein (g/d) | 71 (29) | 71 (35) | 0.98 |

| Protein (% kcals) | 19 (6) | 16 (4) | 0.05 |

| Fat (g/d) | 63 (31) | 65 (31) | 0.81 |

| Fat (% kcals) | 34 (7) | 32 (7) | 0.41 |

| Total sugar (g/d) | 86 (47) | 94 (50) | 0.58 |

| Total sugar (% kcals) | 21 (7) | 22 (7) | 0.73 |

| Added sugar (g/d) | 52 (38) | 61 (42) | 0.46 |

| Added sugar (% kcals) | 12 (7) | 13 (7) | 0.50 |

| Total fiber (g/d) | 16 (10) | 18 (9) | 0.41 |

| Total fiber (g/1000 kcals) | 11 (6) | 11 (7) | 0.73 |

| Insoluble fiber (g/d) | 10 (5) | 12 (6) | 0.17 |

| Insoluble fiber (g/1000 kcals) | 7 (4) | 7 (4) | 0.63 |

| Soluble fiber (g/d) | 4 (2) | 5 (2) | 0.08 |

| Soluble fiber (g/1000 kcals) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 0.17 |

Data are mean (SD).

P-values were calculated using ANOVA. Analyses were based on log scores for the following variables: bench and leg press.

n=51 for dietary analyses. When the dietary data was carefully screened for plausibility of caloric intake by assessing the distribution of the residuals of the linear regression of caloric intake by body weight, one participant was excluded due to a residual that was over 3 standard deviations from the mean. While dietary data on one participant was missing.

When using GLM repeated measures, there were no significant time by maintenance group interaction for any of the health outcomes (i.e., diet, strength, body composition, glucose/insulin indices, and lipids).

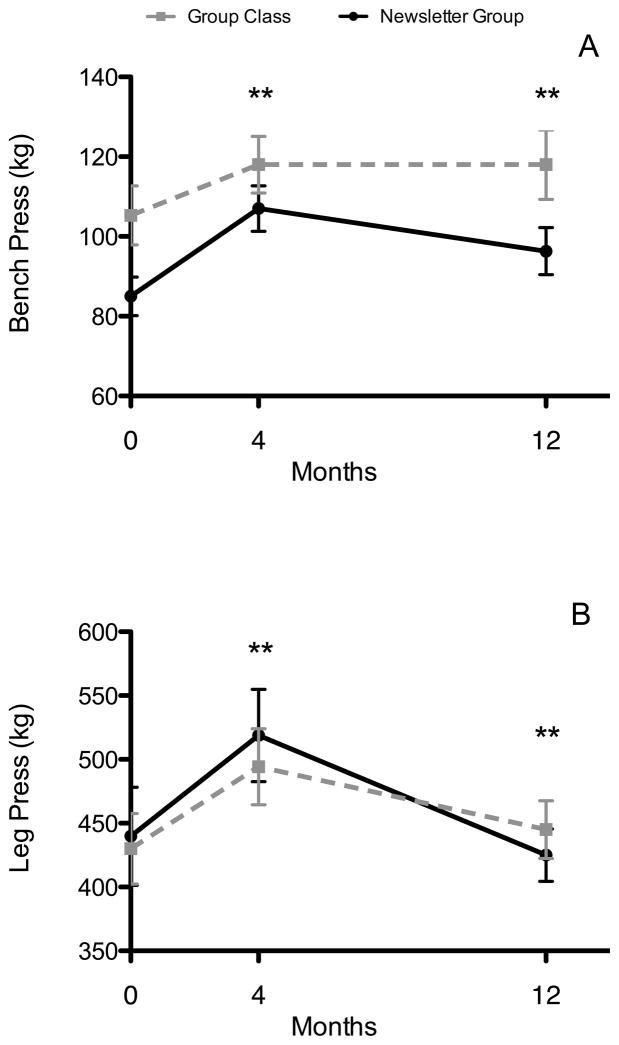

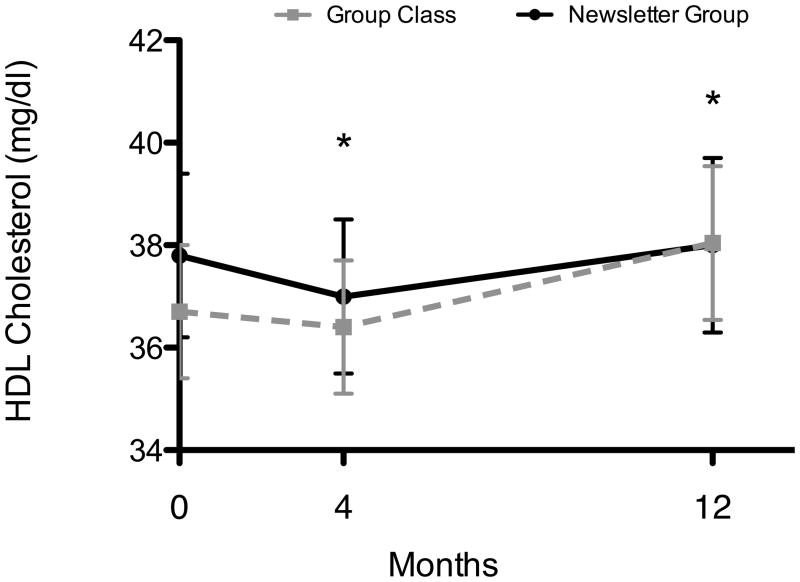

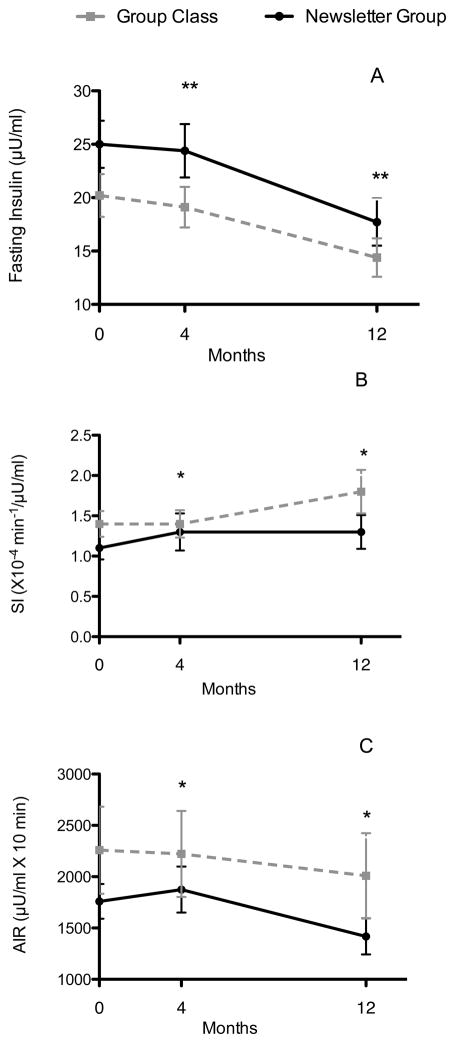

However, there were significant time effects in several health outcomes for both groups from month 4 to 12. In both groups, bench press decreased by 5% (112.5 ±6.4 to 107.2 ±7.3 kg; p=0.004) and leg press decreased by 14% (506.6 ±33.0 to 435.0 ±21.6 kg; p=0.01; Figure 1A & B). There were no significant time effects for any of the dietary variables. From month 4 to 12, both groups significantly increased HDL cholesterol by 5% (36.0 ±1.4 to 38.0 ±1.6 mg/dl; p=0.042; Figure 2). Both groups significantly decreased fasting insulin by 26% (21.8 ±2.2 to 16.1 ±2.0 μU/ml; p<0.001) and decreased acute insulin response by 16% (2048.4 ±322.0 to 1713.5 ±296.0 μU/ml × 10 min; p=0.046), while insulin sensitivity improved by 14% (1.4 ±0.2 to 1.6 ±0.2 ×10−4 min−1/μU/ml; p=0.039; Figure 3A–C).

Figure 2.

(A & B): Changes in leg and bench press over time in the maintenance newsletter group (n=23) and the group class (n=30). Data are presented as mean ±SEM. Changes in strength were calculated using GLM repeated measures. In both groups, bench press and leg press decreased from month 4 to 12; ** p values <0.001.

Figure 3.

Changes in HDL cholesterol over time in the maintenance newsletter group (n=23) and the group class (n=30). Data are presented as mean ±SEM. Changes in HDL cholesterol was calculated using GLM repeated measures. In both groups, HDL cholesterol increased from month 4 to 12; * p values <0.05.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to assess the effects of an 8-month maintenance program, monthly newsletters versus monthly group classes and telephone behavioral sessions, on obesity and metabolic disease risk at one year in overweight minority adolescents. Contrary to our hypothesis, there were no significant differences in any of the health outcomes between the newsletter and group class maintenance groups. However, both maintenance strategies (i.e., monthly newsletter and monthly group classes) resulted in significant improvements in insulin action (increases in SI and decreases in fasting insulin and AIR) and lipids (increases in HDL cholesterol) from month 4 to month 12. These findings suggest that a much less intense 8-month maintenance program (such as monthly newsletters) following an intense intervention is equally effective at improving health outcomes as a more intense maintenance program.

Little research has been conducted to assess the effects of obesity interventions on adiposity and metabolic parameters at one year or longer in children and adolescents, specifically with high-risk minority youth. One study by Wifley et al. (35) with 150 primarily Caucasian, children (7 to 12 years of age) who completed a 5 month intense weight loss program were randomized into one of three maintenance conditions; a) control; b) behavioral skills maintenance (BSM); or c) social facilitation maintenance (SFM). Both the BSM and SFM maintenance conditions resulted in significant reductions in BMI parameters from baseline to 2-year follow-up. Savoye et al. (36) conducted a recent study with 76 ethnically diverse (28% Hispanic) obese children (8 to 16 years of age) who were randomized to a control or lifestyle intervention (group sessions twice weekly for first 6 months and twice monthly for the second 6 months) and completed 24-month follow-up measures. The lifestyle group resulted in significant reductions in BMI, percent body fat, total body fat mass, lipids, and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR at 24 months compared to the control group. Another study by Shalitin et al. (37) with 77 obese children (6 to 11 years of age) who received an intense 12-week intervention of either exercise only (E), diet only (D), or diet plus exercise (D+E), and a subsequent 9 month follow-up. This study found that all groups significantly reduced body fat, BMI, glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, and lipids at 12 weeks but only reductions in body fat and BMI were maintained at the 9-month follow-up. Most notably, Epstein et al. conducted 4 randomized childhood obesity intervention studies, consisting of weekly meetings for 8 to 12 weeks, with monthly meetings continuing for 6 to 12 months and outcome measures collected at baseline, 6 months, 1-, 2-, 3-, 5- and 10 years. At ten years, this intervention reduced obesity parameters, 34% decreased percentage overweight by 20% or more and 30% were no longer obese(9). Another notable long-term intervention was the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH) intervention, which was a randomized, controlled field trial, consisting of 3714 ethnically diverse 6th thru 8th graders. At the 3-year follow up, those participants receiving the intervention showed a decrease in energy intake from dietary fat and an increase in daily vigorous activity, however there were no significant differences found for BMI, blood pressure, or serum lipid and cholesterol levels(38). The majority of these long-term obesity interventions consisted of an intense 4 to 6 month phase of weekly sessions followed by monthly or every other month maintenance phase in subsequent years. None of the above interventions have employed or tested a less intense maintenance period, such as monthly newsletters. More research is warranted to determine which components of obesity interventions and the intensity and mode of delivery that is needed to contribute to long-term behavior change(39).

Our results suggest that the maintenance portion of the intervention can be less intense, such as monthly newsletters, as both maintenance groups had similar improvements in health outcomes. One possible explanation for this is that the material used in both the maintenance groups really focused on and re-emphasized a maximum of three key goals throughout the entire program, i.e., decrease sugar, increase fiber, and strength train. A task force consisting of members of the American Society for Nutrition, the Institute of Food Technologists, and the International Food Information Council recently proposed that future interventions for obesity treatment and prevention should focus on promoting adoption of small changes in nutrition and physical activity(40). Regardless of the mode of delivery used in our study, whether newsletter or group class, the information and material covered was concise and very directed to include small and focused changes in diet and/or exercise. A more focused intervention, with simpler dietary and exercises messages, might be more manageable and sustainable, plus lead to more substantial reductions in adiposity and metabolic diseases in this population. Another possibility is that it simply takes a longer duration follow-up time point to see effects of an intense 16-week intervention. The post-testing immediately following the 16-week intervention might not have been long enough to see the beneficial effects.

Surprisingly, there were no significant changes in health outcomes between those participants who also received the strength training exercises. Both maintenance groups had significant decreases in strength at 1-year, but still had subsequent reductions in metabolic risk factors. We did not expect that once of month of a practical strength training session alone would be enough to maintain or continue increasing strength gains, however, we hypothesized that the personal interaction (of both the practical session and the monthly phone sessions) would encourage the children to continue strength training on their own, especially compared to a newsletter group. It is highly possible, that the strength training components used in the maintenance program simply may not have been intense enough to produce additional health improvements. In addition, the initial 4-month intervention found that participants receiving the N+ST had significant reductions in hepatic fat(24). Unfortunately, we did not measure fat depots at 1-year and we might have seen reductions in hepatic fat at one year in the maintenance group that received a ST component.

We have shown that increased intake of dietary fiber over 16 weeks has been linked to a decreased metabolic syndrome, waist circumference and visceral fat in Latino youth(14, 15). Secondary dietary analyses from the 4-month intervention study demonstrated that participants who decreased added sugar intake over 4 months by an average of 50 g/day had a 33% decrease in insulin secretion(16), and those who increased dietary fiber by 5 g/d had a 10% reduction in visceral adiposity(16). Although diet did not significantly change from month 4 to month 12, the significant reductions in carbohydrates and added sugar seen in the initial 4-month intervention were maintained at 1-year. The results from the maintenance period further highlight that the modified carbohydrate approach may be a successful nutrition strategy for reducing obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors at 1-year in overweight minority adolescents.

There are several limitations that need to be mentioned. First of all, 8-months is still a relatively short-term intervention and longer interventions with long-term follow-up are warranted. Another limitation is there is no true control in the maintenance program. As part of the original 4-month intervention design, protocol and funding, the control participants in the initial 4-month interventions received a delayed intervention, therefore only the participants in the N or N+ST were allowed to participate in the maintenance program. However, our lab has conducted a longitudinal study in over 200 overweight Latino children for the past 10 years, in which extensive measures of adiposity and metabolic parameters are measured annually in order to study that natural progression of type 2 diabetes risk factors in this population. In this cohort, overweight Latino adolescents, essentially with the same inclusion criteria as the current study, not receiving any type of intervention, have significant increases in body fat and deteriorations in insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion and beta cell function over the course of 1-year(15, 41). Of note, conducting non-intervention studies or even control groups in this population is becoming increasingly difficult given that these individuals are at high risk of developing metabolic disorders and agree to participate in a research study in hopes of improving their health and decreasing disease risk. Thus, obtaining “true controls” is ethically and logistically difficult. Regardless, future research should investigate the effects of maintenance interventions compared to true controls on obesity and related risk factors in pediatric populations. The current study is limited by the use of diet records, which rely solely on the participants’ self-reporting and are often prone to errors. However, several steps were taken to ensure the accuracy of dietary data, such as using the well-trained diet technicians to clarify all records, and screening for participants’ comments. Another limitation is that this study was conducted in overweight Latino and African American adolescents, and cannot be generalized to other pediatric populations.

In conclusion, these findings suggest that an intense 4-month intervention, focused on a modified carbohydrate and strength training approach, followed by either an 8-month maintenance program (i.e., monthly newsletters or group classes) could result in significant improvements in risk factors for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors at 1-year in overweight Latino and African American adolescent populations. Hence, newsletters as opposed to group classes may suffice as follow-up programs for overweight teens. Further research exploring maintenance programs and approaches that produce long-term reductions in obesity and related metabolic disease risk are warranted in these high-risk pediatric populations.

Figure 4.

(A–C). Changes in fasting insulin, SI, and AIR over time in the maintenance newsletter group (n=23) and the group class (n=30). Data are presented as mean ±SEM. Changes in insulin indices were calculated using GLM repeated measures. In both groups, fasting insulin and AIR decreased, while SI increased; ** p values <0.001, * p values <0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Dr. Robert C. and Veronica Atkins Foundation, the National Institutes of Cancer (NCI), University of Southern California Center for Transdisciplinary Research on Energetics and Cancer (U54 CA 116848), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (RO1 HD/HL 33064), the National Cancer Institute (Cancer Control and Epidemiology Research Training Grant, T32 CA 09492) and the M01 RR 00043 from NCRR/NIH. We would like to thank the research team as well as the nursing staff at the GCRC. In addition, we are grateful for our study participants and their families for their involvement.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: There are no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau News. Foreign-born a majority in six U.S. Cities. [Accessed on February 2009];Growth fastest in South, Census Bureau Reports. 2000 http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/census_2000/001623.html.

- 2.County of Los Angeles, Department of Health Services Public Health. [Last accessed on February 2, 2010];Obesity on the Rise. 2003 www.lapublichealth.org.

- 3.Weigensberg MJ, Ball GD, Shaibi GQ, Cruz ML, Goran MI. Decreased beta-cell function in overweight Latino children with impaired fasting glucose. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2519–24. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruz ML, Bergman RN, Goran MI. Unique effect of visceral fat on insulin sensitivity in obese Hispanic children with a family history of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1631–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.9.1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goran MI, Bergman RN, Avilla Q, et al. Impaired glucose tolerance and reduced beta-cell function in overweight Latino children with a positive family history of type 2 diabetes. JCEM. 2004;89:207–212. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goran MI, Bergman RN, Cruz ML, Watanabe R. Insulin resistance and associated compensatory responses in African-American and Hispanic children. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2184–90. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toledo-Corral C, Weigensberg MJ, Hodis H, Goran MI. Influence of adiposity, insulin sensitivity, cardiovascular risk factors, and fasting glucose on sub-clinical atherosclerosis in overweight Latino adolescents. Atherosclerosis. 2009;206:594–598. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cruz ML, Weigensberg MJ, Huang T, Ball GDC, Shaibi GQ, Goran MI. The metabolic syndrome in overweight Hispanic youth and the role of insulin sensitivity. JCEM. 2004;89:108–113. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein LH, Valoski A, Wing RR, McCurley J. Ten-year outcomes of behavioral family-based treatment for childhood obesity. Health Psychol. 1994;13:373–83. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.5.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilfley DE, Tibbs TL, Van Buren DJ, Reach KP, Walker MS, Epstein LH. Lifestyle interventions in the treatment of childhood overweight: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Health Psychol. 2007;26:521–32. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.5.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obarzanek E, Kimm S, Barton B, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of cholesterol-lowering diet in children with elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: Seven-year results of the Dietary Intervention Study in Children (DISC) Pediatrics. 2001;107:256–264. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis J, Ventura E, Weigensberg M, et al. The relation of sugar intake to beta-cell function in overweight Latino children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1004–1010. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.5.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis JN, Alexander KE, Ventura EE, et al. Associations of dietary sugar and glycemic index with adiposity and insulin dynamics in overweight Latino youth. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1331–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ventura EE, Davis JN, Alexander KE, et al. Dietary intake and the metabolic syndrome in overweight latino children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:1355–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis JN, Alexander KE, Ventura EE, Toledo-Corral CM, Goran MI. Inverse relation between dietary fiber intake and visceral adiposity in overweight Latino youth. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1160–6. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ventura E, Davis J, Byrd-Williams C, et al. Reduction in risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus in response to a low-sugar, high-fiber dietary intervention in overweight Latino adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:320–7. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis JN, Ventura EE, Shaibi GQ, et al. Reduction in added sugar intake and improvement in insulin secretion in overweight. Latina Adolescents Met Syn Rel Dis. 2007;5:183–193. doi: 10.1089/met.2006.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebbeling C, Leidig M, Sinclair K, Hangen J, Ludwig D. A reduced-glycemic load diet in the treatment of adolescent obesity. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:773–779. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivy JL. Role of exercise training in the prevention and treatment of insulin resistance and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Sports Med. 1997;24:321–36. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199724050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winett RA, Carpinelli RN. Potential health-related benefits of resistance training. Prev Med. 2001;33:503–13. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sothern MS, Loftin JM, Udall JN, et al. Safety, feasibility, and efficacy of a resistance training program in preadolescent obese children. Am J Med Sci. 2000;319:370–5. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200006000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaibi GQ, Cruz ML, Ball GD, et al. Effects of resistance training on insulin sensitivity in overweight Latino adolescent males. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:1208–15. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000227304.88406.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis JN, Kelly LA, Lane CJ, et al. Randomized control trial to reduce obesity related diseases in overweight Latino adolescents. Obesity. 2009;17:1542–1548. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasson RE, Adams TC, Davis JN, et al. Randomized control trial to improve adiposity and insulin resistance in obese African American and Latino adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring) epub doi:10.1038. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:13–23. doi: 10.1136/adc.45.239.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mei Z, Grummer-Strawn LM, Pietrobelli A, Goulding A, Goran MI, Dietz WH. Validity of body mass index compared with other body-composition screening indexes for the assessment of body fatness in children and adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:978–85. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.6.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grundy SM. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2595–600. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cutfield W, Bergman R, Menon R, Sperling M. The modifed minimal model: application to measurement of insulin sensitivity in children. JCEM. 1990;70:1644–1650. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-6-1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connor J, Ball EJ, Steinbeck KS, et al. Comparison of total energy expenditure and energy intake in children aged 6–9 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:643–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.5.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rockett HR, Breitenbach M, Frazier AL, et al. Validation of a youth/adolescent food frequency questionnaire. Prev Med. 1997;26:808–16. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faigenbaum AD, Milliken LA, Westcott WL. Maximal strength testing in healthy children. J Strength Cond Res. 2003;17:162–6. doi: 10.1519/1533-4287(2003)017<0162:mstihc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faigenbaum AWW. Strength and power for young athletes. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deli E, Ryan R. Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilfley DE, Stein RI, Saelens BE, et al. Efficacy of maintenance treatment approaches for childhood overweight: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1661–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savoye M, Nowicka P, Shaw M, et al. Long-term results of an obesity program in an ethnically diverse pediatric population. Pediatrics. 127:402–10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shalitin S, Ashkenazi-Hoffnung L, Yackobovitch-Gavan M, et al. Effects of a twelve-week randomized intervention of exercise and/or diet on weight loss and weight maintenance, and other metabolic parameters in obese preadolescent children. Horm Res. 2009;72:287–301. doi: 10.1159/000245931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nader PR, Stone EJ, Lytle LA, et al. Three-year maintenance of improved diet and physical activity: the CATCH cohort. Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:695–704. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.7.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fulton JE, McGuire MT, Caspersen CJ, Dietz WH. Interventions for weight loss and weight gain prevention among youth: current issues. Sports Med. 2001;31:153–65. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200131030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hill J. Can a small-changes approach help address the obesity epidemic? A report of the Joint Task Force of the American Society for Nutrition, Institute of Food Technologists, and International Food Information Council. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:477–484. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelly LA, Lane CJ, Weigensberg MJ, et al. Parental history and risk of type 2 diabetes in overweight Latino adolescents: a longitudinal analysis. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2700–5. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]