Abstract

Neurotransmitter sodium symporters (NSSs) catalyze the uptake of neurotransmitters into cells, terminating neurotransmission at chemical synapses. Consistent with the role of NSSs in the central nervous system, they are implicated in multiple diseases and disorders. LeuT from Aquifex aeolicus, is a prokaryotic ortholog of the NSS family and has contributed to our understanding of the structure, mechanism and pharmacology of NSSs. At present, however, the functional state of LeuT in crystals grown in the presence of n-octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (β-OG) and the number of substrate binding sites are controversial issues. Here we present crystal structures of LeuT grown in DMPC/CHAPSO bicelles, and demonstrate that the conformations of LeuT-substrate complexes in lipid bicelles and in β-OG detergent micelles are nearly identical. Furthermore, using crystals grown in bicelles and the substrate leucine or the substrate analog selenomethionine, we find only a single substrate molecule in the primary binding site.

Neurotransmitter sodium symporters (NSSs) remove synaptically released glycine, γ-aminobutyric acid, serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine to terminate signal transmission in the central nervous system by coupling neurotransmitter uptake to the sodium electrochemical gradient1–3. The dysfunction of NSSs have been implicated in multiple central and peripheral nervous system diseases including depression4, epilepsy5, orthostatic intolerance6, anxiety4 and Parkinson’s disease4. NSSs are also primary targets of many therapeutic agents and addictive substances that include antidepressants7, antiseizure medications8, anticonvulsants9, cocaine and amphetamines2. Understanding the molecular basis for NSS function, together with the mechanisms of transporter modulation and inhibition by small molecules, requires determining NSS structures by atomic resolution methods, such as X-ray crystallography. At present, however, NSS proteins have proven refractory to crystallization efforts.

LeuT is a prokaryotic NSS ortholog from the hyperthermophilic bacteria Aquifex aeolicus10 and is a valuable paradigm by which to probe relationships between atomic structure and molecular mechanism in NSS proteins. LeuT solubilized in β-OG crystallizes readily and its structure has been solved at high resolution in the presence of substrates10, 11, the competitive inhibitor tryptophan11 and numerous non-competitive inhibitors12, 13. LeuT has also been the focus of multiple spectroscopic studies, including electron paramagnetic resonance experiments14 and single molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer studies15, 16. Furthermore, LeuT has proven a valuable template for homology modeling17, 18, small molecule docking19, 20 and molecular dynamics simulations21 of related eukaryotic NSS proteins, as well as a general guide for design and interpretation of mutagenesis and structure-function studies of NSSs22.

Recently, however, a number of experiments have called into question the extent to which crystal structures of LeuT solubilized in β-OG reflect functionally relevant states of the transporter. Substrate binding, flux and computational studies23, 24 have led researchers to hypothesize that β-OG interferes with the binding of a second substrate to LeuT at the S2 binding site located in the extracellular vestibule and that by binding to this site, β-OG stabilizes an “inhibitor-bound conformation” of the transporter23. Furthermore, they assert that the S2 site, like the S1 site, harbors a high-affinity substrate binding site and that the occupancy of the S2 site by substrate is essential for substrate transport. In contrast, crystallographic10–12, binding and substrate flux studies25 are consistent with a single high affinity substrate site. Because LeuT is the only NSS ortholog that is amenable to high-resolution structural studies, resolving these controversies is crucial to the field. Therefore we set out to crystallize LeuT in a lipid membrane-like environment so that we could study its conformation and substrate binding properties in the absence of β-OG and in the presence of bilayer-compatible lipids.

Here we describe multiple high resolution crystal structures of LeuT crystallized in dimyristroyl phosphatidylcholine (DMPC) and 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPSO) bicelles, a mixture of dialkyl lipid and detergent molecules that is a superior mimic to the native membrane bilayer26,27 in comparison to detergent micelles28. Using LeuT protein purified in n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (C12M) and never exposed to β-OG, we show that the conformations of LeuT-substrate complexes in lipid bicelles are nearly identical to the conformation of the original LeuT-leucine β-OG structure10 except for small differences in loops and crystal contact regions. Additionally, using the new detergent n-heptyl seleno-β-D-glucoside (β-SeHG) we map the detergent sites in crystals grown using micelles, and with n-dodecyl seleno-β-D-maltoside (C12SeM) we probe the binding of detergent to bicelle-derived structures. Most notably, we find only one substrate molecule bound to the transporter, in the primary or S1 binding site. Together, these structures validate the original LeuT structure crystallized in β-OG, they demonstrate that β-OG has little effect on protein conformation, and strongly suggest that there is only a single high affinity substrate site.

RESULTS

LeuT preparation and crystallization

We purified LeuT in the presence of 1 mM leucine (Leu) or selenomethionine (SeMet) (Methods, Fig. 1a) in order to maximize the occupancy of substrate binding sites. We further utilized the detergent C12M during solubilization and purification in order to minimize artifacts from β-OG, such as its binding to the extracellular vestibule23. Following purification, LeuT was incorporated into DMPC/CHAPSO bicelles26, 27, and crystals were grown by vapor diffusion at 20 °C (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Experimental flow chart and lattice contacts in bicelle-based crystal forms. (a) Flow chart defining the detergents and ligands used during purification and crystallization. (b–e) Crystal packing for different crystals forms: C2 (LeuT-Leu; panel b) and P2 (LeuT-Leu; panel c), viewed perpendicular to the b axis; P21 (LeuT-Leu form A; panel d) and P21212 (LeuT-SeMet; panel e), viewed perpendicular to the c axis and a axis, respectively.

The LeuT-leucine complex (LeuT-Leu) in DMPC-CHAPSO bicelles crystallized under two different conditions, yielding crystals with the space groups C2 and P2 and with diffraction limits of 2.5 Å and 3.1 Å, respectively (Table 1). To sensitively detect the presence of substrate(s), we crystallized the LeuT-SeMet complex in two different crystal forms, also using DMPC-CHAPSO bicelles. These crystals belong to the space groups C2 and P21212 and diffract to 2.7 Å and 4.5 Å resolution, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| LeuT-Leu | LeuT-Leu | LeuT-Leu (P21 form A) | LeuT-Leu (P21 form B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.979 | 1.000 | 0.970 | 0.970 |

| Space group | C2 | P2 | P21 | P21 |

| Cell dimensions | ||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 123.8 90.8, 81.6 | 81.2, 84.4, 91.0 | 57.3,179.9, 57.2 | 70.2, 112.5,165.3 |

| α, β, γ (o) | 90.0, 103.8, 90.0 | 90.0, 98.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 89.9, 90.0 | 90.0, 97.6, 90.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 40.0-2.50 (2.59-2.50) | 40.0-3.10(3.21-3.10) | 50.0-3.50(4.14-3.50) | 20.0-4.50(4.66-4.50) |

| Rmerge | 0.08(0.32) | 0.12 (0.52) | 0.14(0.34) | 0.12(0.18) |

| I/σI | 10.2 (2.0) | 11.2 (1.8) | 6.1 (2.1) | 4.6 (4.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.4 (90.4) | 97.0(98.0) | 94.3 (83.4) | 84.0 (80.2) |

| Redundancy | 2.6 (2.4) | 3.1 (3.1) | 2.7 (2.5) | 2.1 (2.0) |

| No. reflections | 29,352 | 21,407 | 13,846 | 12,873 |

| Refinement | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 40.0-2.50 | 40.0-3.10 | 50.0-3.50 | 20.0-4.50 |

| Rwork/ Rfree | 0.21/0.23 | 0.24/0.25 | 0.26/0.31 | 0.26/0.27 |

| No. atoms | ||||

| Protein | 3,968 | 7,936 | 7,936 | 15,872 |

| Ligand/ion | 2Na, 1Leu | 4Na,2Leu | 4Na,2Leu | 8Na,4Leu |

| Water | 63 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| B-factors (Å2) | ||||

| Protein | 46.2 | 69.54 | - | - |

| Ligand/ion | 31.3 | 54.8 | - | - |

| Water (Å2) | 50.4 | 41.5 | - | - |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| Bond angles (o) | 0.689 | 0.698 | 0.609 | 0.518 |

Because the binding of detergent molecules to LeuT is at the center of several controversies, we prepared two detergents, β-SeHG and C12SeM. Crystals in the space group C2, which are isomorphous to the original C2 β-OG crystal form, were grown using LeuT purified and crystallized in β-SeHG. To determine whether there is ordered detergent in the bicelle-derived crystals, we purified LeuT in C12SeM and grew crystals using DMPC-CHAPSO bicelles. The crystals grown from β-SeHG diffract to 2.1 Å resolution (Table 2) whereas those derived from LeuT that were purified in C12SeM and crystallized in bicelles belong to the P21 space group, and diffracted to 3.5 Å and 4.5 Å resolution, respectively (Table 1).

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| LeuT-SeMet | LeuT-SeMet | LeuT-SeMet | LeuT β-SeHG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.979 | 1.200 | 0.970 | 0.979 |

| Space group | C2 | C2 | P21212 | C2 |

| Cell dimensions | ||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 122.3 90.1, 82.0 | 122.3, 90.4, 82.0 | 116.8, 182.7, 81.8 | 89.7, 86.4, 81.4 |

| α, β, γ (o) | 90.0, 103.9, 90.0 | 90.0, 103.6, 90.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 96.2, 90.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 40.0-2.71 (2.81-2.71) | 40.0-3.00 (3.11-3.00) | 40.0-4.50 (4.66-4.50) | 50.0-2.10(2.18-2.10) |

| Rmerge | 0.08 (0.34) | 0.09 (0.37) | 0.09 (0.26) | 0.08(0.48) |

| I/σI | 12.2 (3.4) | 14.1 (4.4) | 18.4(6.2) | 21.0 (2.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.8 (92.2) | 99.9 (100) | 94.6 (83.9) | 97.4 (94.4) |

| Redundancy | 3.1(3.0) | 4.0 (4.0) | 9.1 (7.3) | 5.0 (4.5) |

| No. reflections | 23,553 | 17,133 | 10,449 | 35,135 |

| Refinement | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 40.0-2.71 | 40.0-3.0 | 40.0-4.50 | 50.0-2.10 |

| Rwork/ Rfree | 0.21/0.24 | 0.21/0.22 | 0.24/0.24 | 0.22/0.23 |

| Protein | 3,968 | 3,968 | 7,936 | 3,995 |

| Ligand/ion | 2Na, 1SeMet, 1 I | 2Na, 1SeMet, 1 I | 4Na, 2SeMet | 2Na, 1Leu, 1Cl |

| Water | 24 | 9 | 0 | 99 |

| B-factors (Å2) | ||||

| Protein | 59.3 | 73.7 | - | 31.7 |

| Ligand/ion | 49.9 | 63.9 | - | 21.0 |

| Water (Å2) | 55.7 | 65.0 | - | 35.9 |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.012 |

| Bond angles (o) | 0.647 | 0.627 | 0.527 | 0.578 |

Values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution shells

Structure of LeuT in bicelles

All structures were solved by molecular replacement using the C2 β-OG structure (PBD code 2A65) or the C2 bicelle structures as search probes (Online Methods). These initial structures were then subjected to cycles of crystallographic refinement and manual rebuilding, ultimately yielding structures with good crystallographic and stereochemical statistics. The six structures determined using crystals derived from DMPC-CHAPSO bicelles possessed different lattices harboring distinct protein-protein contacts, thus enabling us to interrogate the structure of LeuT in a range of crystal environments (Fig. 1b–e). A common element to all crystal forms is a ‘parallel’ LeuT dimer, similar to that observed in the original LeuT-β-OG structure10. Matthews coefficient (VM, the crystal volume per unit of protein molecular weight)29 values for these crystals forms range from 2.6 to 3.8 Å3Da−1, giving solvent percentages from 53% to 68%. The P21 crystal form (form A) has a crystal contact interface not previously seen that involves hydrophobic interactions between TM5 helices of non-crystallographic symmetry-related molecules (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1a, b).

Analysis of the refined LeuT-Leu complexes in both the C2 and P2 space groups revealed structures similar to the first LeuT structure obtained from protein crystallized in the detergent β-OG (PDB code 2A65)10 (Table 3). As found previously, the LeuT protomer consists of 12 transmembrane helices (TM1-TM12), multiple solvent exposed loops with two of the long loops – extracellular loops 2 and 4 (EL2 and EL4) – in close juxtaposition. Both structures possess an occluded state conformation in which a single leucine molecule and two sodium ions occupy binding sites approximately half-way across the membrane bilayer, at sites defined largely by TM3, TM8 and the unwound regions of TM1 and TM6. Because the C2 bicelle crystals yielded substantially higher resolution diffraction data than the P2 form, we will use this structure for a detailed structure comparison with the C2 β-OG structure (PBD code 2A65).

Table 3.

Comparison of bicelle-based and C2 β-OG crystal structures

| LeuT-β-OG | LeuT-β-SeHG | LeuT-Leu (C2) | LeuT-Leu (P2) | LeuT-SeMet (C2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LeuT-β-OG | 0 | ||||

| LeuT-β-SeHG | 0.25 | 0 | |||

| LeuT-Leu (C2) | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0 | ||

| LeuT-Leu (P2) | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.76 | 0 | |

| LeuT-SeMet (C2) | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.06 | 0.76 | 0 |

Numbers in the table are RMSD values for main chain atoms following superposition (Å)

Comparison of LeuT structures in bicelles and in β-OG

Superimposition of the C2 bicelle and C2 β-OG crystal structures yields an overall root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 0.73 Å for main chain atoms (Fig. 2a and Table 3), thus demonstrating that the structures are highly similar. Nevertheless, because others23 have stated that TM6a (Pro241-Leu255) adopts a different conformation in molecular dynamics simulations from its conformation in the C2 β-OG structure due to a β-OG molecule bound in the extracellular vestibule instead of a second substrate molecule23, we focused our attention on this transmembrane segment. There is strong electron density for TM6a, thus allowing us to unambiguously define its position (Fig. 2b). Using the overall superposition described above, TM6a in both the C2 bicelle and C2 β-OG structures exhibited essentially identical conformations and positions with an RMSD of 0.14 Å for Cα atoms (Fig. 2c). To test whether there is relative movement between TM6a and ‘scaffold’ helices30, we first superimposed transmembrane helices TM3, TM4, TM5, TM8 and TM12 and then compared the positions of transmembrane helices TM1, TM2, TM6, TM7, TM11 (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Our analysis demonstrates that the conformation and position of TM6a is nearly identical between the C2 bicelle and C2 β-OG crystal structures.

Figure 2.

LeuT crystal structures derived from DMPC-CHAPSO bicelles and n-octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (β-OG) are similar. (a) Stereoview of α-carbon traces of the refined LeuT structures from the C2 bicelle crystal form (cyan) and the C2 β-OG crystal form (PDB code 2A65; magenta) following superposition of corresponding main chain atoms. The regions enclosed by solid, dashed and dotted lines define the TM6a (Pro241-Leu255), TM11-EL6 (Val465-Val483) and EL2 (Val154-Lys163) regions. (b) Electron density for TM6a in the C2 bicelle crystal form. Shown is electron density from a 2Fo-Fc map contoured at 1.5σ. Atoms in TM6a are in stick representation. (c) Close up of TM6a, the carboxyl terminus of TM11 and EL6 (d) and the carboxyl terminus of EL2 (e). Superpositions shown in panels c–e are derived from panel a.

Upon detailed inspection of the C2 bicelle and C2 β-OG crystal structures, however, we find two regions of structural differences in the loop and crystal contact regions. The first region is localized to the carboxyl terminus of TM11, EL6 (the turn between TM11 and TM12) and the beginning of TM12 (Val465-Val483) where the RMSD for Cα atoms is 2.1 Å (Fig. 2d). In comparison to the C2 β-OG structure, the carboxyl terminus of TM11 and EL6 in the C2 bicelle structure is shifted away from TM10. In addition, residues at the C-terminal end of TM11 (Ile472-Ile475) adopt a 310-helix conformation in the C2 β-OG crystal structure, whereas in the C2 bicelle structure, this region adopts an α-helical structure. We suggest that these differences are because there are six detergent molecules near this area in the C2 β-OG structure, and because they are absent in the C2 bicelle structure, there are rearrangements in local conformation at the end of TM11 and EL6 (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Indeed, one of the β-OG molecules of the C2 β-OG crystal form makes direct contact with residues at the end of TM11 and EL6.

The C-terminus of TM11 and TM12 also participate in subunit-subunit contacts in the LeuT dimer, and differences in the C2 bicelle and C2 β-OG crystal forms result in slightly different subunit-subunit contacts, such that superposition of one subunit does not result in the superposition of the second subunit (Supplementary Fig. 2b). An additional manifestation of these differences can be seen upon the inspection of Trp481, a residue at the beginning of TM12 (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c). In the C2 β-OG structure, the indole rings of symmetry-related Trp481 residues are oriented ‘tip to tip’ and the alkyl groups of β-OG molecules insert into the dimer interface. By contrast, in the C2 bicelle structure, the indole rings make extensive contacts by stacking against one another. Indeed, the differences in the contacts between Trp481 residues is likely coupled to variations in lattice contacts and, in the C2 β-OG crystal form, there are interactions between TM11 of one molecule and TM12, IL1, and IL5 in the symmetry-related molecule (Supplementary Fig. 3a). These contacts involve electrostatic interactions between Glu470 and Arg508, Lys474 and Tyr82, and Glu477 and Lys431, interactions that are absent in the C2 bicelle crystal form.

The second region of structural difference is localized to EL2 (Val154-Lys163) (Fig. 2e). Here, the local RMSD for Cα atoms between the C2 bicelle and C2 β-OG structures is 1.3 Å. Because these residues are involved in crystal contacts in the C2 β-OG crystal form but not in the C2 bicelle form, these conformational distinctions are straightforwardly attributable to differences in crystal contacts (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Interestingly, the two regions of structural difference between the C2 bicelle and C2 β-OG crystal forms are not observed upon comparison of the P2 bicelle and C2 β-OG structures. Indeed, the P2 bicelle structure superimposes extraordinarily well with the C2 β-OG structure with an overall RMSD of 0.38 Å for main chain atoms (Table 3). This close agreement of the two structures is undoubtedly grounded in the fact that despite the difference in space groups, the two unit cells are closely related and the protein molecules have nearly identical lattice contacts (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). We note, nevertheless, that the carboxyl terminus of TM11 (Ile475-Glu478) in the P2 bicelle form is disordered, thus rendering a direct comparison of the same region in the C2 β-OG form not possible.

Despite the overall congruence of the P2 bicelle and C2 β-OG structures, there are nevertheless two regions of difference localized to loops and crystal contacts. The first change involves the EL4 region (Val308-Phe331). In the P2 bicelle crystal structure, the sharp turn (Gly318, Ala319 and Phe320) between EL4a and EL4b in P2 bicelle is positioned about 1 Å closer to the substrate binding site in comparison to its position in the C2 β-OG structure (RMSD=1.1 Å for Cα atoms; Supplementary Fig. 3c). This difference may be attributed either to the flexibility of this loop, the details of the crystallization conditions or both. The second change is localized to the C-terminal end of TM11 at Pro473 and Lys474 (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Here the P2 bicelle structure deviates substantially from the C2 β-OG structure, as defined by an RMSD of 2.1 Å for Cα atoms, which may be attributed to the absence of β-OG molecules around TM11.

Locations of bound detergent molecules

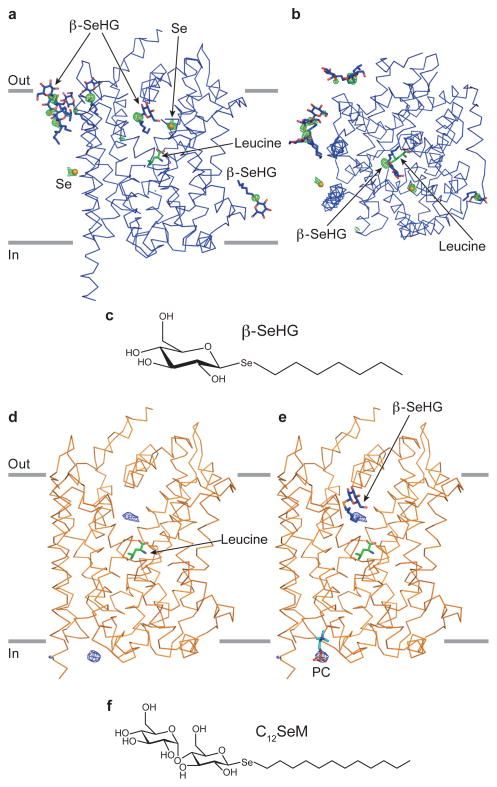

Multiple studies23, 24 state that the β-OG is an inhibitor of LeuT and by binding to the transporter it results in the formation of “an inhibitor bound” conformation distinctly different from a functional, substrate-bound conformation. As part of our effort to understand the interplay between the binding of β-OG to LeuT and its structure and function, we sought to unambiguously map detergent binding sites in the C2 β-OG crystal form and to determine whether, in the bicelle-derived crystal form, there are any bound detergents carried over from the purification of the transporter in C12M. To do this, we synthesized novel selenium (Se)-containing detergents (Fig. 3) that would allow us to sensitively map detergent sites by anomalous scattering x-ray diffraction experiments.

Figure 3.

Mapping detergent sites in LeuT. (a) The anomalous difference Fourier map for LeuT (blue) crystallized in n-heptyl-β-D-selenoglucoside (β-SeHG). The map is contoured at 5σ, depicted in green mesh and unambiguously shows the positions of bound detergent molecules. Seven β-SeHG molecules are modeled and shown in stick representation. The positions of two additional β-SeHG molecules are inferred based on strong anomalous difference peaks. Here we have only modeled the Se atoms (orange spheres) due to weak electron density for the headgroups and alkyl chains. Leu in the primary site is shown in stick representation (green) with several residues omitted for clarity. (b) The anomalous difference map for LeuT-β-SeHG viewed from extracellular side of the protein. (c) The chemical structure of β-SeHG. (d) The Fo-Fc difference electron density map for LeuT-Leu (P21 form A, chain A, orange) crystallized in bicelles. The protein was purified using the detergent n-dodecyl-β-D-selenomaltoside (C12SeM). This map is displayed at 4.5σ, depicted in blue mesh. (e) The two peaks in panel d are in the similar positions as the alkyl chain of β-SeHG in LeuT-β-SeHG structure and the phosphocholine molecule (PC) in LeuT-Leu (C2 form) structure, respectively. Both β-SeHG and PC molecules are shown as stick representation. (f) The chemical structure of C12SeM.

We first determined that β-SeHG is a faithful analog of β-OG and that LeuT purified in β-SeHG forms well-diffracting crystals that are isomorphous to C2 β-OG crystals. On the basis of anomalous difference Fourier maps derived from C2 β-SeHG crystals, we unambiguously identified nine β-SeHG molecules (Fig. 3a, b), five of which were located in the same position as the β-OG molecules previously defined in the LeuT-β-OG structure. In addition, we mapped four additional β-SeHG molecules located between TM3 and TM4, between TM10 and TM11, within the extracellular vestibule and near the 2-fold crystallographic axis adjacent to TM12. The first of the additional β-SeHG molecules is adjacent to a previously mapped detergent molecule that is proximal to TM4, with the head group packed against the main-chain carbonyl oxygen from Leu126 and the alkyl chain enclosed by Phe167, Leu126 and Ile120. The second molecule is near TM11 and TM10. Because of the weak electron density for the alkyl chain and head group, we only mapped the position of the selenium atom. Nevertheless, based on a small conformational change within the region of Val462 to Tyr471, relative to the C2β-OG structure (RMSD for Cα atoms is 0.5 Å), we speculate that the aliphatic chain forms direct hydrophobic interaction with the indole ring of Trp467. This speculation also echoes the observation from the LeuT-Trp structure (PDB code 3F3A)11, in which the alkyl chain of a β-OG molecule in the similar position is enclosed by Ile410, Val413, Leu463 and Trp467. The third β-SeHG molecule is located in the extracellular vestibule where the alkyl chain of β-SeHG is in a hydrophobic pocket formed by side chains of Leu25, Leu29, Ile111, Phe253, Phe320, Leu400. This molecule shares a very similar position to the β-OG molecule (PDB code 3GJD)23 and has been proposed to act as an inhibitor of LeuT, supposedly displacing a substrate molecule from the S2 binding site and distorting the conformation of TM6a23. The last detergent is located close to the 2-fold axis of TM12. Again, we only modeled the selenium atom because of the weak electron density of head group and alkyl chain.

Unfortunately, in the first bicelle-derived LeuT-Leu crystals (P21 form A) prepared using protein purified in C12SeM, we were not able to measure the anomalous signal of C12SeM because of the twin properties of this crystal form (about 40% twin fraction). However, from Fo-Fc electron density maps we found two prominent peaks located around IL1 and the extracellular vestibule, respectively (Fig. 3d). After superimposing this P21 bicelle structure with the high resolution C2 bicelle and LeuT-β-SeHG structures, we found the peak around IL1 is in a position similar to the phosphocholine molecule modeled in C2 bicelle structure, while the other peak in the vestibule is close to the alkyl chain of β-SeHG in LeuT-β-SeHG structure (Fig. 3e). Based on these parallels, we suggest that the peak around IL1 corresponds to a phosphocholine molecule and the peak in the vestibule corresponds to the alkyl chain of a lipid molecule. Because we were able to detect the phosphocholine group in an Fo-Fc map, we should be able to detect Se in C12SeM in the same difference maps. Thus because there are no other prominent peaks in Fo-Fc electron density maps resulting from bicelle-derived crystals for which LeuT was prepared in C12SeM, we suggest that there are no tightly bound detergent molecules in these LeuT crystals from bicelles.

In addition, we crystallized another type of LeuT-Leu crystal (P21 form B) that was prepared using protein purified in C12SeM, which had different cell dimensions from the previous P21 form A structure (Table 1). More importantly, we were able to measure the anomalous signal of C12SeM because there is no twin fraction in this crystal form. Not unexpectedly, we found no significant peaks in anomalous difference Fourier maps calculated using diffraction data measured at the Se K absorption peak (Supplementary Fig. 4), thus further demonstrating that there are no tightly bound detergent molecules. These results suggest that unlike β-OG, C12M does not occupy the extracellular vestibule and that it is unlikely that the transporter structure in bicelles is perturbed by the presence of bound C12M detergent molecules.

Determination of substrate site and stoichiometry

The number of high-affinity substrate binding sites in the occluded-state form of LeuT is a highly contentious topic. On the one hand, some15, 23, 24 argue that there are two high affinity sites. On the other hand, experiments from another group10–12, 25 are entirely consistent with a single high affinity site. The first group states that β-OG displaces a substrate molecule from the secondary or S2 site and that is why, in the C2 β-OG crystal structures, no substrate is observed in the S2 site. Because we defined the conditions under which to grow well-ordered LeuT crystals in the absence of β-OG and in the presence of bilayer-like bicelles, we decided to examine whether we could locate a second substrate molecule in the S2 site by x-ray diffraction methods. To do this, we carried out two different experiments.

We first carefully examined the electron density in the C2 bicelle crystals of the LeuT-Leu complex in which 1 mM Leu was present throughout purification, crystallization and cryoprotection. In doing this, we clearly identified one leucine molecule and two sodium ions in the primary binding pocket on the basis of unbiased Fo-Fc ‘omit’ electron density maps (Fig. 4a, b), which were exactly like those seen in the original C2 β-OG crystal structure10. If the putative S2 binding site is also a high-affinity substrate site, then we should find similar electron density in the S2 site, near Ile111 and Leu400 (ref. 23, 24). However, we could not find a similar electron density in the putative S2 site (Fig. 4a, b). Instead, we found only a small egg-shaped electron density feature in the extracellular vestibule, approximately 4.7 Å from Ile111, 5.8 Å from Arg30 and 6.8 Å from Leu400. We assert that this density is not attributable to a bound leucine molecule for two reasons. First, the shape of the density is not well fit by a Leu molecule. Second, the density is not strong enough to be a well ordered Leu molecule and if we do model a Leu molecule in this position, the resulting B-factor of 111 Å2 is more than twice that of the mean B-factor of 46.2 Å2. Although it is difficult to conclusively define molecular identity at 2.5 Å resolution, we modeled different entities into the density and compared the refined B-factors. When we fit a single water or a Cl ion to the density the resulting B-factors were 32 Å2 and 61 Å2, respectively. However, analysis of anomalous difference maps measured from crystals grown in the presence of iodide did not yield any prominent peaks near this electron density feature (Supplementary Fig. 5a) and thus we suggest that this density is due to the presence of several water molecules or the alkyl chain from a lipid molecule.

Figure 4.

LeuT has a single high affinity substrate site in bicelles. (a) Electron density map for the primary substrate binding site and extracellular vestibule in the DMPC-CHAPSO bicelle C2 crystal form of the LeuT-Leu complex. The substrate leucine in the primary site (green) is in stick representation and two sodium ions are shown as black spheres. Key residues in the vestibule are in stick representation. The Fo-Fc difference electron density map is displayed at 3σ, depicted in blue mesh and calculated with the substrate leucine and the two sodium ions omitted (Leu and Na are shown for reference). (b) Close up of primary binding site and the vestibule. (c) Anomalous difference Fourier map for primary substrate site and extracellular vestibule derived from diffraction data measured from LeuT-SeMet (C2 form) crystals. The map is contoured at 5σ and 20σ and depicted in green and red mesh, respectively. SeMet was positioned in the primary site and shown in stick representation. Sodium ions Na1 and Na2 are illustrated as black spheres (d) Close up of primary binding site and the vestibule.

We next purified LeuT and grew crystals in the presence of the substrate analog SeMet, knowing that if there is any substantial occupancy of the S2 site by a substrate molecule, we would easily pick it up in anomalous difference Fourier maps. We obtained two different bicelle-based crystal forms of the LeuT-SeMet complex, one of which strongly diffracted x-rays beyond 2.7 Å resolution. Most importantly, after careful analysis of maps from both crystal forms, we found that there is strong anomalous difference electron density in the primary or S1 site (24 σ) but no significant anomalous difference electron density in the putative S2 site or anywhere else in the transporter (Fig. 4c, d and Supplementary Fig. 5b, c).

To verify that SeMet is a bona fide substrate of LeuT we would ideally carry out substrate flux experiments using 3H-SeMet. This isotope, however, is unavailable. Therefore we asked whether SeMet inhibits LeuT catalyzed 3H-Ala flux to the same extent as Met, a known substrate11. From these experiments we found that 1 mM SeMet inhibits 3H-Ala uptake by LeuT to a similar extent as 1 mM Met (Supplementary Fig. 6), consistent with our hypothesis that SeMet is a faithful analog of Met and that SeMet should therefore label the substrate binding sites. Taken together, these diffraction experiments using bicelle-derived crystals are consistent with the conclusion that there is a single high affinity substrate site in LeuT.

DISCUSSION

The LeuT-substrate structures observed from multiple-crystal forms in DMPC-CHAPSO bicelles provide excellent molecular blueprints by which to explore fundamental molecular principles of structure, mechanism and pharmacology in NSS family members. The striking similarity between the structures in lipidic environments and detergents suggests that the overall conformation of the substrate-bound, occluded state of LeuT is largely independent of crystal environment and condition, with exceptions made for the local conformations of a few surface exposed loops that include EL2, EL4 and EL6. Indeed, these three loops are likely dynamic in nature and, in the context of NSS proteins, have been implicated in conformational dynamics associated with substrate translocation, on the basis of biochemistry and spectroscopic studies14, 31–33.

Our results further demonstrate that the original LeuT structure crystallized in β-OG micelles represents a functional conformational state of the transporter. We suggest that this is the case based on detailed comparisons of the bicelle and β-OG structures of LeuT, for which we find that β-OG molecules do not substantially affect the overall conformation of LeuT. The most substantial differences between β-OG and bicelle-based crystal structures are localized to loops and are likely the consequence of differences in the detergent-lipid environment and the lattice contacts. Indeed, the conformational differences that we detect in TM11 and EL6 upon comparing the LeuT-β-OG with our bicelle-derived LeuT-Leu structures prompt us to compare our analysis with a recent electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analysis which demonstrated that the distance between E478C in TM11 and E236C in EL3 becomes closer when β-OG is added to LeuT in the presence of Leu and Na ions14. Although this relative distance change was interpreted as a movement of TM6a14, our analysis suggests that that the bound β-OG molecule in the extracellular vestibule does not affect the conformation of TM6a and that the salient conformational change is rooted in the movements of TM11 and EL6 that are due to their interactions with β-OG molecules on the periphery of the protein.

The fact that we could not observe substrate in the proposed S2 site23, 24 of these bicelle-derived structures demonstrates that even when LeuT is purified in C12M and crystallized in a membrane-like environment, we are unable to visualize a substrate in the S2 site. A confounding issue in resolving differences between structural studies and functional studies is that β-OG detergent has been regularly used in crystallization experiments10–12, while C12M has been employed in binding assays23–25. Indeed, a β-OG molecule was identified in the extracellular vestibule of LeuT in a previous study23 and also in the work reported here. Most importantly, the previous study suggests that the presence of β-OG interferes with measurement of stoichiometry in LeuT23. Because we entirely avoided β-OG in these bicelle-based crystal forms, the crystallographic studies reported here offer visualization of the substrate sites of LeuT in the absence of β-OG, thus demonstrating that β-OG cannot account for the differences that the two other groups observed in the substrate binding stoichiometry of LeuT10,11, 15, 23–25. We further note that tricyclic antidepressants with micromolar affinity to the S2 site compete with the β-OG molecule bound to the vestibule, readily occupying the S2 site in the crystal12. These observations beg the question of why a substrate, with nanomolar affinity23, cannot similarly bind to the S2 site. While we found non-protein electron density in the extracellular vestibule of the bicelle-derived LeuT structures, we suggest that it represents the alkyl chain of a lipid molecule or several ordered water molecules.

SeMet was used to further investigate whether the non-protein electron density in the extracellular vestibule could be attributed to a partially occupied substrate. Extensive prior work has shown that SeMet is a good substitute for Met as judged by the similar activity and properties of selenomethionyl and natural proteins34, by the similarity of SeMet and Met as determined from comparisons of their high resolution crystal structures35, and by the similarity of SeMet and Met functions in biosynthesis36. Based on the fact that SeMet is generally a viable analog of Met and that it inhibits 3H-Ala uptake similar to Met, we employed it to probe the substrate binding sites in LeuT.

The resulting anomalous difference electron density maps from LeuT-SeMet structures demonstrate that the non-protein density in the extracellular vestibule is unlikely attributable to a substrate molecule and that there is a single SeMet molecule bound to the S1 site. Whereas the different stoichiometry of substrate binding to LeuT determined from functional studies23–25 might be attributed to different biochemical methodologies37, the structural data presented here show that LeuT crystallized in lipid bicelles contains a single high-affinity substrate-binding site. Nevertheless, our data do not rule out the possibility that the proposed S2 site may be a transiently occupied, low affinity binding site for substrate as it moves from the extracellular vestibule to the S1 site11,38.

In conclusion, the multiple LeuT structures in complex with substrate and substrate analog in lipid bicelles are consistent with the original LeuT β-OG structure. Because β-OG has only minimal effects on LeuT conformation, our analysis demonstrates that the LeuT structures crystallized in β-OG are functional forms of the transporter and in all likelihood represent functionally relevant states along the transport cycle of LeuT.

ONLINE METHODS

Protein expression, purification and crystallization

LeuT was expressed and purified as described previously10 with two exceptions. In purification of the LeuT-leucine (LeuT-Leu) complex, 1 mM L-leucine was included in all solutions and n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (C12M) was the only detergent utilized throughout the purification. After cleavage of the octa-histidine tag by thrombin, the LeuT-Leu complex was further purified by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 1mM Leu and 0.7 mM C12M. Bicelles were prepared by mixing dimyristroyl phosphatidylcholine (DMPC) and 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPSO) at a molar ratio of 2.8:1 with water to yield a final concentration of 35% (w/v)27. LeuT-Leu (8–10 mg ml−1) in the presence of 7% (w/v) DMPC-CHAPSO bicelles was crystallized by vapor diffusion at 20 °C with the crystallization reservoir solution containing 100 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5–5.0), 25%–35% (v/v) MPD and 5%–10% (v/v) PEG400. For LeuT in n-dodecyl-β-D-selenomaltoside (C12SeM) (Anatrace), 0.7 mM C12SeM was substituted for C12M in the final size exclusion chromatography stage. Crystals were directly flash frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to collection of x-ray diffraction data.

The LeuT-SeMet complex was purified as described for the LeuT-Leu complex, except that 0.1–1 mM SeMet was included in all solutions. In the final size-exclusion chromatography stage, we used 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl or NaI, 1 mM SeMet and 0.7 mM C12M. Bicelles used for crystallization of the LeuT-SeMet complex were prepared by replacing 10% (w/v) of DMPC with 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DMPE). For growth of the LeuT-SeMet crystals (P21212 form) there was 50 mM NaCl in the SEC buffer, while for the LeuT-SeMet crystals (C2 form) NaCl in the SEC buffer was replaced with 50 mM NaI. LeuT-SeMet crystals (P21212 form) were grown in the presence of 7% (w/v) DMPC-DMPE-CHAPSO bicelles at 20 °C in crystallization buffer with 100 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.1), 32% (v/v) MPD, 8.5% (v/v) PEG400, 50 mM MgCl2, and 100 mM urea. LeuT-SeMet crystals (C2 form) were grown in crystallization buffer with 100 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.7), 35% (v/v) MPD, 10% (v/v) PEG400, 50 mM MgCl2.

LeuT-β-SeHG was purified and crystallized as described previously10 except that n-heptyl-β-D-selenoglucoside (β-SeHG) (Anatrace) was substituted for n-octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (β-OG) in the final size-exclusion chromatography stage.

Data collection and structure elucidation

Diffraction data sets were collected at the Advanced Light Source (beamlines 5.0.2 and 8.2.1) and the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory, beamlines 24-ID-E and 24-ID-C). Data sets were indexed, integrated and scaled using HKL2000 software39.

The LeuT-Leu structures (C2 and P2 forms) were determined by molecular replacement with Phaser40 using the original LeuT-β-OG structure (PDB code 2A65) as a search probe. After an initial solution was found, Phenix41 was used to generate the simulated annealing composite omit electron density maps. Following manual adjustment in Coot42 into the composite omit maps, refinement of the model against the X-ray data using Phenix was carried out until satisfactory model statistics were obtained. Regions with weak electron density were excluded in the final model. The final C2 bicelle LeuT-Leu model consists of residue 5-131, 135-509 of LeuT, one leucine, two sodium ions, one phosphocholine headgroup, one decane molecule, one acetate, one polyethylene glycol and 63 water molecules.

The LeuT-SeMet (C2 form and P21212 form) and LeuT-Leu (two P21 forms) structures were determined by molecular replacement using the LeuT-Leu (C2 form) above as a search probe. The LeuT-Leu (P21 forms) and LeuT-SeMet (P21212) structures are low resolution structures and only rigid body, NCS and TLS refinements were performed.

The structure quality analysis was carried out using Molprobity43. For all structures, Ramachandran geometry is excellent, with at least 97% of the residues in the most favored regions and none in disallowed regions. All structure figures were generated with PyMOL44.

Anomalous map calculation

For the LeuT-SeMet (C2 and P21212 forms), LeuT-Leu (new P21 form) and LeuT β-SeHG crystallographic analysis, the anomalous difference maps were calculated using the fast Fourier transform in the CCP445 suite. The anomalous difference electron density map for P21212 LeuT-SeMet was then subjected to real space averaging between the two subunits in the asymmetric cell using the “NCS map” tool of the Coot program42.

Inhibition of transport assay

LeuT was reconstituted into lipid vesicles as described before10–12. Transport was performed at 27°C by diluting LeuT proteolipsomes into 60-fold into external buffer (20 mM Hepes-Tris (pH 7.0), 100 mM NaCl) containing 50 nM 3H-Ala (83 Ci mmol−1) alone, with 1 mM L-Met, and with 1 mM L-SeMet, respectively. Reactions were terminated in five minutes by removing 150 uL aliquots of the reaction into 1.5 ml cold internal buffer (20 mM Hepes-Tris (pH7.0), 100 mM KCl). Reactions were filtered and analysed as previously described10–12. Non-specific uptake was determined by performing the experiment using liposomes devoid of protein. The entire experiment was performed twice and each time in triplicate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Shaffer for crystallization and measurement of diffraction data for the LeuT-β-SeHG complex; K. Wang and A. Penmatsa for assistance with LeuT expression and purifications; R. Hibbs for suggestion in structure refinement; M. Kavanaugh and D. Claxton for comments, L. Vaskalis for assistance with illustrations. We also thank the staff at beamlines 24-ID-E and 24-ID-C of the Advanced Photon Source, and the staff at 8.2.1 and 5.0.2 of the Advanced Light Source. This work was supported by the NIH. E.G is investigator with Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

H.W. and E.G. designed the research; H.W., J.E. and E.G. performed the research and analyzed the data; and H.W. and E.G. wrote the paper.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ACCESSION CODES

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for LeuT–Leu (C2 bicelle), LeuT–Leu (P2 bicelle), LeuT-Leu (P21 form A bicelle), LeuT-Leu (P21 form B bicelle), LeuT-SeMet (C2 bicelles), LeuT-SeMet (C2 bicelle, collected at 1.2Å), LeuT-SeMet (P21212 bicelle) and LeuT-β-SeHG (C2 β-SeHG) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with codes 3USG, 3USI, 3USJ, 3USK, 3USL, 3USM, 3USO and 3USP, respectively.

References

- 1.Masson J, Sagne C, Hamon M, Mestikawy SE. Neurotransmitter transporters in the central nervous system. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:439–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amara SG, Sonders MS. Neurotransmitter transporters as molecular targets for addictive drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gouaux E. The molecular logic of sodium-coupled neurotransmitter transporters. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 2009;364:149–154. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn MK, Blakely RD. Monoamine transporter gene structure and polymorphisms in relation to psychiatric and other complex disorders. Pharmacogenomics J. 2002;2:217–235. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richerson G, Wu Y. Role of the GABA transporter in epilepsy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2004;548:76–91. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-6376-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shannon JR, et al. Orthostatic intolerance and tachycardia associated with norepinephrine-transporter deficiency. New Eng J Med. 2000;342:541–549. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002243420803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White K, Walline C, Barker E. Serotonin transporters: implications for antidepressant drug development. AAPS J. 2005;7:E421–E433. doi: 10.1208/aapsj070242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalby NO. Inhibition of γ-aminobutyric acid uptake: anatomy, physiology and effects against epileptic seizures. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;479:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Frolund B, Frydenvang K. GABA uptake inhibitors. Design, molecular pharmacology and therapeutic aspects. Curr Pharmaceut Design. 2000;6:1193–1209. doi: 10.2174/1381612003399608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamashita A, Singh SK, Kawate T, Jin Y, Gouaux E. Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of Na+/Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporters. Nature. 2005;437:215–223. doi: 10.1038/nature03978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh SK, Piscitelli CL, Yamashita A, Gouaux E. A competitive inhibitor traps LeuT in an open-to-out conformation. Science. 2008;322:1655–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.1166777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh SK, Yamashita A, Gouaux E. Antidepressant binding site in a bacterial homologue of neurotransmitter transporters. Nature. 2007;448:952–956. doi: 10.1038/nature06038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Z, et al. LeuT-desipramine structure reveals how antidepressants block neurotransmitter reuptake. Science. 2007;317:1390–1393. doi: 10.1126/science.1147614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Claxton DP, et al. Ion/substrate-dependent conformational dynamics of a bacterial homolog of neurotransmitter:sodium symporters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:822–829. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Y, et al. Substrate-modulated gating dynamics in a Na+-coupled neurotransmitter transporter homologue. Nature. 2011;474:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature09971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Y, et al. Single-molecule dynamics of gating in a neurotransmitter transporter homologue. Nature. 2010;465:188–193. doi: 10.1038/nature09057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Field JR, Henry LK, Blakely RD. Transmembrane domain 6 of the human serotonin transporter contributes to an aqueously accessible binding pocket for serotonin and the psychostimulant 3,4-methylene dioxymethamphetamine. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11270–11280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.093658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forrest LR, et al. Mechanism for alternating access in neurotransmitter transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10338–10343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804659105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinning S, et al. Binding and orientation of tricyclic antidepressants within the central substrate site of the human serotonin transporter. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8363–8374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.045401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beuming T, et al. The binding sites for cocaine and dopamine in the dopamine transporter overlap. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:780–789. doi: 10.1038/nn.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kniazeff J, et al. An intracellular interaction network regulates conformational transitions in the dopamine transporter. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17691–17701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800475200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanner BI, Zomot E. Sodium-coupled neurotransmitter transporters. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1654–1668. doi: 10.1021/cr078246a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quick M, et al. Binding of an octylglucoside detergent molecule in the second substrate (S2) site of LeuT establishes an inhibitor-bound conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5563–5568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811322106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi L, Quick M, Zhao Y, Weinstein H, Javitch JA. The mechanism of a neurotransmitter: sodium symporter--inward release of Na+ and substrate is triggered by substrate in a second binding site. Mol Cell. 2008;30:667–677. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piscitelli CL, Krishnamurthy H, Gouaux E. Neurotransmitter/sodium symporter orthologue LeuT has a single high-affinity substrate site. Nature. 2010;468:1129–1132. doi: 10.1038/nature09581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faham S, Bowie JU. Bicelle crystallization: A new method for crystallizing membrane proteins yields a monomeric bacteriorhodopsin structure. J Mol Biol. 2002;316:1–6. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faham S, Ujwal R, Abramson J, Bowie JU, Larry D. Practical aspects of membrane proteins crystallization in bicelles. Curr Top Membr. 2009;63:109–125. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ostermeier C, Michel H. Crystallization of membrane proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:697–701. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthews BW. Solvent content of protein crystals. J Mol Biol. 1968;33:491–497. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boudker O, Verdon G. Structural perspectives on secondary active transporters. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:418–426. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smicun Y, Campbell SD, Chen MA, Gu H, Rudnick G. The role of external loop regions in serotonin transport. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36058–36064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephan MM, Chen MA, Penado KMY, Rudnick G. An extracellular loop region of the serotonin transporter may be involved in the translocation mechanism. Biochemistry. 1997;36:1322–1328. doi: 10.1021/bi962150l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell SM, Lee E, Garcia ML, Stephan MM. Structure and function of extracellular loop 4 of the serotonin transporter as revealed by cysteine-scanning mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24089–24099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311173200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huber RE, Criddle RS. The isolation and properties of β-galactosidase from Escherichia coli grown on sodium selenate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1967;141:587–599. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(67)90187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hendrickson WA, Horton JR, LeMaster DM. Selenomethionyl proteins produced for analysis by multiwavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD): a vehicle for direct determination of three-dimensional structure. EMBO. 1990;9:1665–1672. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mudd SH, Cantoni GL. Selenomethionine in enzymatic transmethylations. Nature. 1957;180:1052–1052. doi: 10.1038/1801052a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reyes N, Tavoulari S. To be, or not to be two sites: that is the question about LeuT substrate binding. J Gen Physiol. 2011;138:467–471. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Celik L, Schiøtt B, Tajkhorshid E. Substrate binding and formation of an occluded state in the leucine transporter. Biophys J. 2008;94:1600–1612. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.117580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otwinowski Z, Minor W, Carter Charles W., Jr Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams PD, et al. Phenix: A comprehensive python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen VB, et al. Molprobity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeLano WL. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collaborative Computing Project. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.