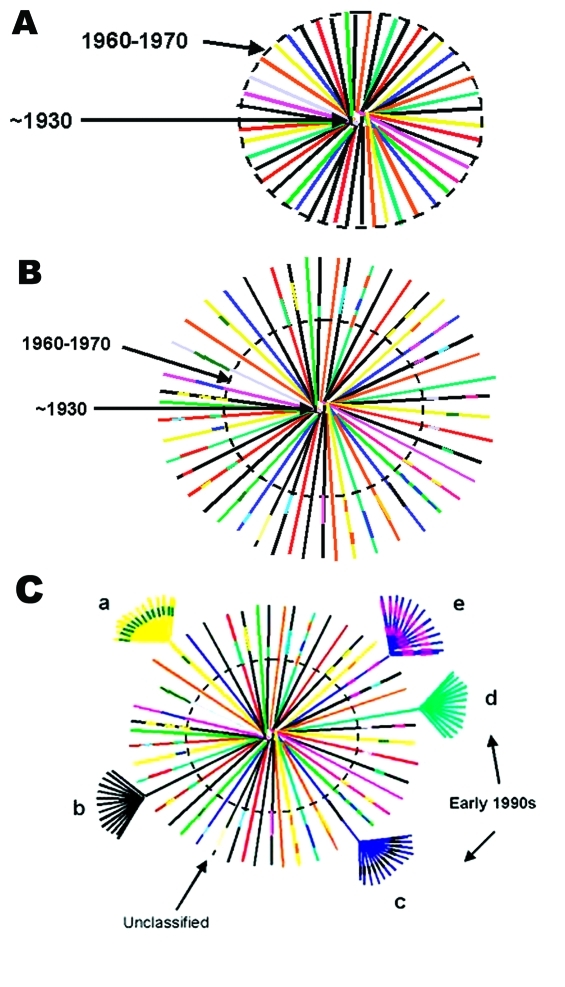

Figure 3.

Hypothetical model of HIV-1, group M evolution. A. Star phylogeny representing the evolution of the ancestral HIV-1, group M virus that was able to adapt in humans and was transmitted among rural populations in central Africa from approximately the 1930s (22). Over time, the viruses would have become increasingly genetically distinct from each other and the original parental strain. The dotted circle denotes the beginning of migration from these remote areas to cities in central Africa (approximately 1960–1970). B. Recombinant lineages (outside the dotted circle), represented by multicolored lines indicating mosaic viruses or genetic mixes of the circulating strains, would have been the result of population migration, urbanization, patterns of sexual activity, and medical practices (two of the oldest, fully characterized sequences, MAL [1985] and Z321 [1976], were both recombinant viruses from Zaire). Recombinant viruses would have continued to be generated and transmitted until introduced into high-risk populations, such as commercial sex workers, taxi drivers, commercial truck drivers, or long-distance truck drivers, and then rapidly transmitted within and between these social networks. Such high-risk social networks throughout central Africa were responsible for the rapid expansion of a relatively small number of evolving viruses, including recombinant strains, locally, regionally, and eventually globally. These epidemiologic groupings are represented as clusters of highly related strains at the end of a few HIV-1 lineages. Panel C shows what phylogenetic analysis of global HIV-1 strains collected in the early 1990s, when sequence characterization first began, and after being exported out of central Africa, would have looked like. The clusters of related sequences from founder viruses, which were disseminated globally, would have appeared as subtypes or clades, arbitrarily labeled a–e. Occasionally, strains that were not widely expanded were identified and designated as unclassifiable. From this hypothetical modeling, and the high numbers of recombinant strains, it seems unlikely that only pure subtypes were exported from this region of Africa to establish mini-epidemics in other countries. Therefore, at least some of what we currently define as pure subtypes most likely arose from recombinant genomes originally generated somewhere in central Africa.