Abstract

Novel fluorescent tools such as green fluorescent protein analogs and Fluorogen Activating Proteins (FAPs) are useful in biological imaging to track protein dynamics in real-time with low fluorescence background. FAPs are single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) selected from a yeast surface display library that produce fluorescence upon binding a specific dye or fluorogen that is normally not fluorescent when present in solution. FAPs generally consist of human immunoglobulin variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) domains covalently attached via a glycine and serine rich linker. Previously, we determined that the yeast surface clone, VH-VL M8, could bind and activate the fluorogen dimethylindole red (DIR), but that the fluorogen activation properties were localized to the M8VL domain. We report here that both NMR and X-ray diffraction methods indicate the M8VL forms non-covalent, anti-parallel homodimers that are the fluorogen activating species. The M8VL homodimers activate DIR by restriction of internal rotation of the bound dye. These structural results, together with directed evolution experiments of both VH-VL M8 and M8VL, led us to rationally design tandem, covalent homodimers of M8VL domains joined by a flexible linker that have a high affinity for DIR and good quantum yield.

The development of fluorescent technologies has revolutionized cellular imaging and molecular biology, and the utility of genetically encoded fluorescent proteins, such as green fluorescent protein (GFP), for the detection of particular proteins of interest is well documented (1). There is still a need for additional, well-characterized tools that provide real-time, high signal-to-noise fluorescence and demonstrate high fluorescence quantum yield (ϕf), photo-stability, and a broad spectral range. Fluorogen Activating Proteins (FAPs) are part of novel, immunoglobulin-based, fluoromodule platforms that induce fluorescence emission of cognate fluorogenic dyes in solution (2). FAPs cause a dramatic increase in the ϕf or fluorescence enhancement of the fluorogenic dyes that they bind. These fluoromodules have enhanced photo-stability due to exchange of bleached dye. Their fluorescence emission spans the visible spectrum from blue to far red, comparable to other fluorescence proteins, and often a single FAP can activate multiple dyes (3) (4) (5). The fluorogenic dyes bound by FAPs have low fluorescence background in aqueous solution and increase in fluorescence as much as two-thousand fold upon interaction with a cognate FAP protein. Previous studies give some insight into the generation of fluorescence from fluorogens, showing that these compounds become fluorescent when the rotation of the aromatic functional groups are restricted by a binding partner, such as upon intercalation into DNA (6).

Several FAPs were isolated that activate the red (640nm) emitting fluorogenic dye, dimethylindole red (DIR) (3). These FAPs are isolated from a naïve human IgG single chain Fv (scFv) library created in a yeast surface display vector typically consisting of IgG variable heavy (VH) and light (VL) chain domains covalently connected by a flexible linker comprised of serine and glycine repeat sequences (7) (8) (9). Two of these FAPs, named VH-VL M8 and VH-VL K10, were unusual in that they both contained identical VL domains but different VH domains. Based on the sequence similarity between M8 and K10 it was proposed, and demonstrated experimentally, that the VL domain alone was sufficient in the yeast surface display format to bind and activate DIR (10).

The VL domain of M8 provides the opportunity to investigate the potential for optimization of DIR fluoromodules. Improvements in the ϕf and the dye affinity of fluoromodules is desirable, so that they will produce stronger fluorescence intensities for light microscopy at lower dye concentrations. Previously isolated FAPs have ϕf that compare favorably to other fluorescent proteins, yet the extent by which DIR-activating FAPs can be improved in their ϕf has not yet been determined (2). In order to improve the characteristics of FAP-fluorogen pairs, FAP genes can be subjected to directed evolution, utilizing PCR-based mutagenesis, transformation back into yeast and selection by a fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) (11) (12). Because the VH-VL M8 FAP is active in both the original isolated VH-VL (scFv) format, as well as an isolated VL domain (M8VL), we were able to compare the directed evolution of this FAP in the two different formats. The aim of this study was to better understand the mechanism for DIR activation by the M8VL FAP, in particular determination of the conformational restraints placed on DIR. Following the directed evolution experiments, rational design of the linker region and structural analysis of the active form of the M8VL FAP were undertaken to more fully understand this unusual interaction and the mechanism by which the M8VL FAP can activate DIR. This study describes the first structural data for FAP-induced fluorescence activation of the environmentally-sensitive fluorogen DIR.

Experimental Procedures

Directed Evolution

Directed evolution of VH-VL M8 andM8VL genes was accomplished through error-prone PCR, homologous recombination and FACS enrichment as previously described (2) (11). Three rounds of FACS enrichment of a library of mutants with a 106 diversity was performed at 250 pM DIR for VH-VL M8 and 1 nM DIR for the M8VL domain. At the final round of sorting, cells were autocloned onto induction plates and visually screened for fluorescence enhancement (3). Further detail regarding the directed evolution enrichments for M8VHVL and M8VL is available in the Supporting Information Figure S1. Plasmid DNA from individual clones was isolated using the Zymoprep Yeast Plasmid Miniprep Kit II (Zymogen Inc) and transformed into bacterial MachT1 cells (Invitrogen). Bacterial mini prep DNA was isolated (Fermentas) and the altered genes were commercially sequenced by Retrogen.

Affinity, fluorescent enhancement and quantum yield determination

The dissociation constant (KD) of purified soluble FAPs and yeast cell surface displayed FAPs for DIR were determined by titrations of DIR into samples as previously described (3). The KD values for soluble monomeric FAPS (e.g. VH-VL) was obtained by fitting the binding data to the standard quadratic binding equation (eq. 1) using in-house software that finds both the global and local minima in χ2.

| (1) |

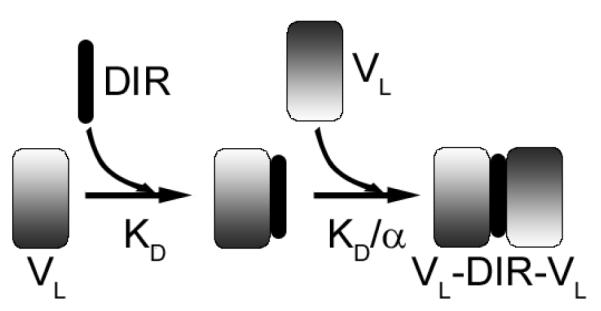

[PT] is the total concentration of the protein, and [LT] is the total concentration of the dye. Fitting synthetic data sets indicated that it is possible to distinguish KD values as low as 0.1 nM with the protein concentrations used in this study (see supporting information S11A and S11B). In the case of VL FAPs that dimerize in solution due to the addition of DIR (M8VL, M8VLSL55P, Q9) a number of different binding models are possible: i) formation of VL-VL dimers followed by dye binding, or ii) dye binding to one VL monomer, followed by the addition of the second VL domain. The second model was selected based on NMR data that showed that both M8VL and M8VLSL55P are monomeric in solution at concentrations of ~500 μM. Consequently, the binding curves were fit to the model illustrated in Scheme 1, using the equations provided by Mack et al (13). In this case, the concentration of the intermediate species VL-DIR was assumed to be small, based on NMR studies with both M8V and M8VLSL55P. Consequently α was set at 107 to ensure that [(VL)2DIR] > [VL-DIR]. The overall dissociation constant for the reaction, (KD)2/α, was insensitive to the choice of α for values of 105 or higher. Note that the overall dissociation constant for this reaction reports on both the dye-protein interaction (KD) and the interaction of the free protein with the protein-dye complex (KD/α). Since we cannot determine α independently, we report the overall affinity, (KD)2/α. For both models, the fitted parameters were the KD, the fluorescence at saturation, FMax, and the total protein concentration [PT]. In the case of M8VL, a plot of χ2 versus [PT] yielded a number of essentially equivalent local minima, in which case the minimum closest (within 10%) to the experimentally measured protein concentration was selected. Errors in KD were obtained by generating random data sets, assuming the error for each data point followed a normal distribution, and then determining the distribution of the resultant KD values. Because of the high affinity associated with the synthetic tandem dimers it was not possible to compare the effect of the serine to proline mutation (M8VL versus M8VLSL55P) on the affinity of DIR when these FAPs were in the dimer form. However, a quantitative comparison was possible using the isolated VL domains because the apparent affinity can be controlled by the judicious choice of the protein concentration.

Scheme I.

DIR binds to VL domain with a dissociation constant KD, forming VL-DIR. The binding of a second VL then occurs with a dissociation constant KD/α where α represents a cooperativity parameter.

Binding data for FAPs on the yeast surface were fit using as single-site binding model, assuming that the concentration of free DIR equaled the total amount of DIR, e.g.

| (2) |

A preliminary FACS screen was run prior to all titration assays to determine levels of cell surface FAP expression and non-viable yeast cells on all FAP constructs, including uninduced control samples. Fluorescence enhancement measurements were performed as described previously (2).

Quantum yields were determined as previously described (5) utilizing two cross-calibrated reference standards Cy5.18 and Cresyl Violet based on the spectral overlap with DIR, and data analyzed with Origin or GraphPad (14).

Cloning and Protein Expression and Purification

M8VL tandem dimer genes were constructed using the wild-type gene and a synthetic, E. coli codon-optimized, M8VL gene (DNA 2.0) that altered the nucleotide sequence but not the aminoacid sequence, in order to avoid homologous recombination of the duplicated genes. The synthetic M8VL gene was ligated into the 5′ end of the wild type M8VL using the NheI and BamHI restriction sites in the pPNL6 plasmid containing the wild-type M8VL gene. Clones were sequenced to confirm presence of the 5′ synthetic gene and the (G4S)3 linker region followed by the 3′ wild type gene.

Tandem dimers of M8VL with longer (G4S) repeats in the linker were constructed by inserting oligomers of differing lengths into the BamHI restriction site at the beginning of the (G4S) linker of pPNL6-M8VL tandem dimer described above. The oligomer pair for adding one (G4S) repeat was (5′GATCAGGTGGCGGTGGCAGCA3′) and (5′GATCTGCTGCCACCGCCACCT3′). The oligomer pair for inserting three (G4S) repeats was (5′GATCAGGTGGCGGTGGCAGCGGCGGTGGTGGTTCCGGAGGCGGCGGTTCTA3′) and (5′GATCTAGAACCGCCGCCTCCGGAACCACCACCGCCGCTGCCACCGCCACCT3′). Complementary oligomers were annealed by incubating the oligomer for 5 minutes at 95°C and then cooling slowly to 23°C prior to ligation in buffer (50mM potassium acetate, 20mM Tris-acetate pH 7.9, 10mM magnesium acetate, 1mM dithiothreitol). DNA sequencing confirmed insertion of the extended linker oligomers.

All genes were PCR amplified with primers containing non-identical SfiI restriction sites that are compatible with the SfiI sites in the hexahistidine containing pAK400 E. coli periplasmic expression vector (gift from A. Plückthun). These primers are (5′GGCCCAGCCGGCCATGGCGGGTTCTGCTAGCCAGCCTGTGC3′) and (5′GGCCCCCCAGGCCGCTAGGACGGTGACCTTGGTCC3′). M8V , a mutant M8VLSL55P and all tandem dimer SfiI-tailed PCR products were blunt cloned into the pJET plasmid (Fermentas), sequenced, and then inserted into pAK400 via SfiI sites. Selected genes were also cloned into pPNL9 yeast secretion plasmid by gap repair and transformation into the yeast strain YVH10 as previously described (2).

M8V and M8VLSL55LP proteins were produced in milligram quantities for crystallographic studies from the pAK400 vector in E. coli MachT1 (Invitrogen) cells. Typically, 3 grams of cells from 0.5L of culture were lysed in 20mLs of buffer (50mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 750mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X100 and 0.05% Tween-20) for 10 minutes in a cell homogenizer (Avestin EmulsiFlex-C3). The lysate was centrifuged for 30 minutes at 28,000g and the supernatant fraction batch bound to nickel agarose resin (ThermoFisher). The nickel resin was washed in ten column volumes of buffer (20mM imidazole, 10mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 50mM KH2PO4 and 300mM NaCl), followed by ten column volumes of buffer (20mM imidazole, 10mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 50mM KH2PO4 and 750mM NaCl) and two column volumes of buffer (50mM imidazole, 10mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 50mM KH2PO4 and 300mM NaCl). The protein was recovered in elution buffer (250mM imidazole, 10mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 50mM KH2PO4 and 300mM NaCl). Proteins were further purified by ion exchange chromatography on a HiTrap XP XL column (GE Healthcare) following dialysis into 50mM MES pH 6.0 and 50mM NaCl. A linear gradient of NaCl from 50mM to 1M was used to elute the protein from the ion exchange column. Protein preparations were analyzed by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis to determine purity. M8VL was further purified by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200, 10/30 column in 0.2M Tris pH 7.5, 0.15M NaCl.

To allow labeling with 13C for NMR experiments the M8VL gene was transferred from the pAK400-M8VL vector, using flanking NdeI and HindIII sites (enzymes from New England Biolabs), into pET22b+ plasmid (Novagen). Studier’s minimal media was used to produce labeled M8VL (50 mM Na2HPO4, 50 mM KH2HPO4, 25 mM (15NH4)2SO4, 0.5% glucose, 1X Trace metals, 2mM MgSO4 ) (15). The 15N source was (15NH4)2SO4 and the 13C source was glucose, both from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. The labeled protein was purified essentially as described above.

Crystallization, data collection, and structure determination

Crystal structures were determined for M8VL, M8VL with DIR and M8VLSL55P with DIR. Data collection and refinement statistics for the three structures are summarized in Table 3. For all three structures, data were processed with HKL-2000 (16), phases were determined by molecular replacement using Phaser (17), and model building and refinement were carried out with Coot (18), Refmac5 (19), and Phenix (20). The coordinates are numbered by the Kabat convention (21).

Table 3.

Data collection and refinement statistics for M8VL and M8VLSL55P

| Data collection | M8VL(no DIR) | M8VL+DIR | M8VLSL55P+DIR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beamline | ALS 4.2.2 | APS 23-ID-B | APS 23-ID-B |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.000 | 1.033 | 0.722 |

| Resolution (Å)a | 1.45 (1.48-1.45) | 1.50 (1.53-1.50) | 1.96 (1.98-1.96) |

| Space group | C2221 | P21212 | P43212 |

| a,b,c (Å) | 83.66, 93.64, 30.57 | 73.90, 83.53, 35.14 | 83.49, 83.49, 76.35 |

| # of observations | 80,786 (2233) | 250,067 (11,950) | 240,775 (12,015) |

| # of unique reflections |

21,290 (830) | 35,526 (1758) | 20,018 (977) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.7 (79.2) | 99.9 (100.0) | 100.0 (100.0) |

| Rsym (%)b | 4.3 (31.7) | 8.7 (53.7) | 8.7 (54.9) |

| average I/σ | 30.1 (2.4) | 28.2 (4.2) | 35.5 (4.9) |

|

| |||

| Refinement statistics all refl. > 0.0σF | |||

|

| |||

| Resolution (Å) | 29.2-1.45 | 41.8-1.50 | 37.3-1.96 |

| # reflections (working set) |

20,190 | 33,690 | 18,888 |

| # reflections (test set) |

1090 | 1779 | 1048 |

| Rcryst (%)c | 17.9 | 14.8 | 20.9 |

| Rfree (%)d | 20.8 | 18.3 | 24.2 |

| # of protein atoms | 845 (29 in alternate conformations) |

1670 (70 in alternate conformations) |

1662 (14 in alternate conformations) |

| # of DIR atoms | 0 | 32 (32 in alternate conformations) |

32 (18 in alternate conformations) |

| # of waters | 127 | 319 (8 in alternate conformations) |

138 |

|

| |||

| # of solvent atoms | 51 | 12 | 33 |

|

| |||

| Average B-values (Å2) | |||

|

| |||

| Chain A | 18.9 | 11.7 | 32.5 |

| Chain B | NA | 15.5 | 46.6 |

| DIR | NA | 16.0 | 27.6 |

| Wilson B-value (Å2) | 15.1 | 11.7 | 26.6 |

|

| |||

| Ramachandran Plot | |||

|

| |||

| Most favored | 90.3 | 90.7 | 85.4 |

| Additionally allowed |

8.6 | 8.2 | 12.9 |

| Generously allowed | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 |

| Disallowede | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

|

| |||

| R.M.S. deviations | |||

|

| |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | .006 | .005 | .011 |

| Angles (Å) | 1.12 | 1.30 | 1.45 |

Numbers in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell of data.

Rsym= ∑hkl ∣I- <I>∣ / ∑hkl I

Rcryst = ∑hkl ∣Fo-Fc∣ / ∑hkl ∣Fo∣

Rfree is the same as Rcryst, but for 5% of the data excluded from the refinement

Residue Asn51, which is in a conserved γ turn and is almost always found in this region in antibody structures.

The M8VL was co-crystallized with DIR by mixing M8VL (15 mg/ml in 0.2M Tris, 0.15M NaCl, pH 7.5) with a 5:1 molar excess of DIR (10 mg/ml; in 20% DMSO, 0.2M Tris, 0.15M NaCl, pH 7.5). Initial crystallization conditions were identified by screening 384 different solutions with the Topaz System (Fluidigm) (22) and the crystal used for data collection was grown at 22°C in a sitting drop with a well solution of 35% PEG 1500. The crystal was cryoprotected with a mixture of 90% well solution and 10% PEG 200, and cryocooled by plunging into liquid nitrogen. Data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source, beamline 23-ID-B to a resolution of 1.50Å, and the structure was determined by molecular replacement using the lambda light chain variable domain from Fab 2219 (PDB code 2b0s) as a starting model. The final model (PDB code 3T0W) contains two M8VL molecules in the asymmetric unit (residues A1-108, B1-108), two half-occupancy DIR molecules, 2 chloride ions, 2 PEG molecules, and 319 waters, and has Rcryst and Rfree values of 14.8% and 18.3%, respectively.

The M8VL (15 mg/ml in 0.2M Tris, 0.15M NaCl, pH 7.5) in the absence of DIR was crystallized at 22°C in sitting drops with a well solution of 2M ammonium sulfate, 2% PEG 400, 0.1M HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid), pH 7.5, that represented a condition originally identified using the JCSG/ IAVI CrystalMation robot (Rigaku) and screening 384 different conditions at two different temperatures. The crystals were cryoprotected with a mixture of 70% well solution, 30% ethylene glycol, and cryocooled by plunging into liquid nitrogen. Data were collected at the Advanced Light Source, beamline 4.2.2 to a resolution of 1.45Å. The structure was determined by molecular replacement with search model coordinates consisting of one VL domain from the previously determined M8VL structure. The final model (PDB code 3T0V) contains one unliganded M8VL molecule in the asymmetric unit (residues A1-110), 127 waters, and 1 Tris, 1 sulfate ion, 4 ethylene glycol, and 2 PEG molecules. The final Rcryst and Rfree values are 17.9% and 20.8%, respectively.

The M8VLSL55P co-crystallized with DIR was formed by mixing M8VLSL55P (3 mg/ml) with a 10 fold molar excess of DIR (10 mg/ml in 20% DMSO, 0.2M Tris, 0.15M NaCl) and concentrating the mixture to 15mg/ml. Initial crystallization screening was carried out with the CrystalMation robot and the crystal used for data collection was grown in a sitting drop with a well solution of 0.25M ammonium sulfate, 30% PEG 4000. The crystal was cryoprotected with a mixture of 70% well solution and 30% ethylene glycol and cryocooled by plunging into liquid nitrogen. Data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source, beamline 23-ID-B to a resolution of 1.95Å and the structure was determined by molecular replacement using one VL domain from the M8VL structure as starting model. The final model (PDB code 3T0X) contains two M8VLSL55P molecules (residues A1-108, B1-106), one DIR molecule with two alternate conformations for the indole moiety, 1 sulfate ion, 7 ethylene glycol molecules and 147 waters. Final Rcryst and Rfree values are 20.9 and 24.0.

NMR Analysis

Purified M8VL protein was dialyzed into buffer (10mM Na2HPO4 pH 6.3, 250 mM NaCl) with 0.75mM each of arginine and glutamate to reduce aggregation and 0.02% azide (23).The protein was concentrated to 0.9 mM for NMR relaxation experiments. The M8VL fluoromodule with DIR was formed using a 4:1 molar ratio of lyophilized DIR that was resuspended into the dialyzed protein sample and incubated overnight. NMR experiments were performed with a Bruker 600MHz NMR spectrometer fitted with a cryoprobe at 304K. The spectra were processed with NMRPipe (24). The T1, T2 and heteronuclear NOE experiments (25) on 15N labeled material were analyzed using NMRViewJ (26). In-house scripts were used to further analyze the data and prepare the input files for Relax-NMR(27) (28) (29) (30) (31). The global correlation times, τm, were determined using the ‘model-free.py’ script available in Relax-NMR (32) (33) (34).The theoretical values for global correlation time were obtained using HYDRONMR program (35). Standard multi-nuclear NMR sequences (36) (37) were used in conjunction with 15N and 13C labeled material to obtain resonance assignments for mainchain atoms in the unliganded complex utilizing an in-house Monte Carlo based assignment program (38). Inter-proton NOEs were obtained from 15N separated NOESY experiments that detected either the 1H frequency, or the 13C frequency of the attached carbon, of protons that were dipolar coupled to NH protons (39).

Calculation of protein-DIR van der Waals Energies

CHARMM version 33b2 (40) was used to compare van der Waals energies using the top aa22 parameter file. Bond lengths, angles, and planar torsional angles for DIR were obtained from the X-ray coordinate files described in this paper. Standard non-bonded atom parameters were used for aliphatic and aromatic carbons and hydrogens in DIR. The protein-DIR system was minimized with 100 steps of steepest decent and then adopted basis set Newton Raphson minimization was applied until the energy converged. During the minimization the protein mainchain N,Cα and carbonyl carbons were constrained to positions in the original X-ray structure. The difference between the van der Waals energy for the protein plus DIR minus the protein without DIR was used to determine the contribution of protein-DIR interactions to the van der Waals energy.

Results

Directed evolution of the VH-VLM8 FAP

In order to determine if changes in affinity and quantum yield can increase fluorogenicity of the VH-VL M8, directed evolution was performed using FACS selection for increased fluorescence of yeast surface displayed FAP at low DIR concentration (8). The FACS enrichment selections were carried out at 250 pM DIR after determining the yeast cell surface affinity of VH-VL M8 is 1.2nM (Supporting Information S1, Panels A-C). Each round of enrichment and selection monitored both the amount of yeast surface expression and intensity of DIR fluorescence signal of cells in the mutagenized population. Single cells were isolated during the third cycle of enrichment as described previously (9). Individual clones of interest were identified based on visual inspection for increased fluorescence on induction plates compared to the wild type VH-VL M8. Amino-acid changes were identified by DNA sequencing. DIR ϕf and fluorescence enhancement of cell surface displayed FAPs were then determined by FACS analysis of individual clones. The equilibrium dissociation constants for isolated clones from directed evolution were initially determined in order to identify mutants with enhanced binding to DIR (Supporting Information Figure S2). These measurements identified three classes, as determined from sequence length and alignment to the original VH-VL M8, from a total of twelve single clones (Supporting Information Figure S3 and S4).

The first class of isolated clones, which have both VH and VL domains, is represented by L9 in Table 1 (see S2 for binding curves of FAPs on the yeast surface, and S5 for the binding curves of soluble Q9 and J8), the yeast surface display fluorescence enhancement of this clone was increased five-fold over the parent M8. Sequence analysis revealed several amino-acid changes in the VH domain of the clone VH-VL L9: FH29S, WH36C, AH93V, IH113iT according to Kabat numbering system (H113i is an extension of Kabat numbering based on extra residues on the C-terminus of the M8 heavy chain) (21).

Table 1.

Characteristics of clones isolated from directed evolution of VH-VL M8 and M8VL FAPs.

| Clone name |

Format | Fluorescence enhancement (YSD)* |

Soluble KD or KD2/α |

ϕ f | Mutations in sequence different from wild type (VH-VL M8 or M8VL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M8 | VH-VL | 1.0 | ND | ||

| L9 | VH-VL | 5.7X | ND | FH29S, WH36C, AH93V, IH113iT |

|

| Q9 | VL | 3.8X | 1.3±0.3×10−15 M2 | 0.19 | QL1R, TL14I,D L30G,QL37R, SL55P, FL62L, SL80P |

| J8 | VL-VL | 6.4X | <0.1 nM† | VL#1: DL85N, KL103T, LL107S, IL108iT VL#2: SL9P, SL32P |

|

| M8VL | VL | 3.7X | 2.5±0.7×10 15 M2 | 0.71 | |

| M8VL SL55P |

VL | 8.2X | 1.0±0.5×10−16 M2 | 0.58 | SL55P |

Fluorescence enhancement is calculated as DIR fluorescence signal normalized for cell surface expression for each individual clone, divided by the equivalent value for the wild type parent (VH-VL M8). The concentration of Q9 was 33 nM, J8 was 9 nM, M8VL was 10 nM, M8VLSL55P was 135 nM.

Data were equally well fit to a wide range of Kd values less than 0.11 nM.

A second class of clones, which have only the VL domain, is represented by Q9 in Table 1. This clone displayed an increased fluorescence enhancement of four-fold above the VH-VL M8 parent. Sequence analysis revealed that this clone contained 7 mutations in the VL: QL1R,TL14I, D L30G, QL37R, SL55P, FL62L, SL80P, in addition to suffering deletion of the VH domain (Supporting Information Figure S4).

A third class represented by one clone, J8, had a six fold increase in fluorescence enhancement compared to the parent VH-VL M8 (Table 1). This clone is remarkable in that it is a “pseudodimer” gene containing two tandem-linked VL domains, presumably generated by recombination during the yeast gap repair process used in the creation of the directed evolution library. Each of the two VL domains retains approximately 95% homology to the VL domain of parent VH-VL M8 (Supporting Information Figure S6). The VL-VL J8 pseudodimer displayed six total amino-acid substitutions in both light domains. Four changes were present in the N-terminal light chain, DL85N, KL103T, LL107S, IL108iT and an additional two changes were present in the C-terminal light chain, SL9P, SL32P. The pseudodimer contains 12 residues that do not align to the M8VL sequence and are located prior to the flexible linker. These residues align with the region of the VH M8 that is N-terminal to the linker. They are described as AL108a,SL108b, TL108c , KL108d, GL108e, PL108f,SL108g,GL108h,TL108i,LL108j, GL108k because they are not found in conventional antibodies and are an addition to the typical Kabat numbering scheme (Supporting Information Figure S7). Homologous recombination is likely to have generated these additional residues as well.

Directed evolution of the M8VL FAP

Directed evolution of M8VL was performed as described above using a DIR concentration of 1 nM during FACS sorting (Supporting Information Figure S1, Panels D-F). This selection generated a single class of clones, represented by clone A4 in Table 1, with a greater than 8 fold increase in fluorescence enhancement compared to the parent M8 VL-DIR (Table 1). All 16 clones from this class contained only one change of serine to proline at position 55 (SL55P). This clone is subsequently referred to as M8VLSL55P, in accordance with Kabat nomenclature.

Characterization of tandem homodimers of M8VL FAPs on the yeast cell surface

The isolation of a tandem linked VL-VL J8 pseudodimer from the directed evolution of VH-VL M8 led us to engineer tandem homodimer genes of the M8VL domain and investigate the effect of different (G4S) linker lengths on fluorescence enhancement. Yeast cell surface expression and fluorescence enhancement measurements of clones with different linker lengths were performed. There was no significant difference in DIR affinity of tandem homodimers with extended (G4S) linkers based on cell surface affinity measurements (Supporting Information S8). None of the linker lengths were less than (G4S)3 (15 amino acids) and thus not predicted to form diabodies or triabodies (41) (42). Fluorescence enhancement was increased two-fold for homodimers containing the (G4S)4 or (G4S)6 linkers. The tandem homodimer gene made from the M8VLSL55P domain produced a FAP with a three-and-a-half fold increased fluorescence enhancement compared to the similar tandem homodimer made with the M8VL domain (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of altering glycine-serine rich linker length in tandem homodimers created from the M8VL.

| Clone | (G4S) repeats in linker |

Fluorescence Enhancement (YSD)* |

Soluble KD | ϕ f |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dM8VL(G4S)3 | 3 | 1.0 | <0.1† nM | 0.38 |

| dM8VL (G4S)4 | 4 | 2.0 | <0.1† nM | 0.64 |

| dM8VLSL55P(G4S)6 | 6 | 2.0 | <0.1† nM | 0.55 |

| dM8VLSL55P(G4S)3 | 3 | 3.4 | <0.1† nM | 0.14 |

Fluorescence enhancement is calculated as DIR fluorescence signal normalized for cell surface expression for each individual clone, divided by the equivalent value for the M8VL. The concentration of dM8VL (G4S)3 was 3 nM, dM8VL(G4S)4 was 3 nM, dM8VL(G4S)6 was 3nM, and dM8VLSL55P was 12 nM.

Data were equally well fit to Kd values less than 0.1 nM.

Characterization of VH-VL M8, M8VL and tandem VL homodimer FAPs as soluble proteins

To verify that the affinity of the FAPs for DIR is not influenced by the yeast surface display of the protein, we attempted to express soluble versions of these FAPs. The parent VH-VL M8 FAP showed a remarkable affinity for DIR on the yeast cell surface (KD = 1.2nM); however, a KD for the soluble protein produced by yeast secretion could not be determined by fluorescence measurements (Supporting Information Figure S9); the purified VH-VL M8 protein showed a complete absence of fluorogen activation. To date, no other FAP proteins that we have characterized have shown strong affinity or activity by cell surface titration measurements but a complete lack of activity when assayed as a soluble protein. The yield of yeast secreted protein from VH-VL M8 was unexpectedly low, based on the typically strong correlation of yeast secretion yield and yeast surface display (43) (44). Thus, further biochemical characterization of soluble VH-VL M8 protein was not possible due to low protein expression levels by either yeast secretion or bacterial expression (data not shown). Similarly, no characterization was possible for purified proteins from any of the clones from directed evolution that contained the VH domain of VH-VL M8 (such as VH-VL L9), due to poor protein expression levels (data not shown). However, the purified soluble VL-VL J8 pseudodimer protein has a KD for DIR of less than 0.1nM (Table 1). This dissociation constant is similar to that found for the synthetic VL dimer (M8VL(G4S)3), however the low KD values for these two proteins precludes an accurate comparison of their KD values. Determination of ϕf for J8 FAP was not possible due to low protein yield.

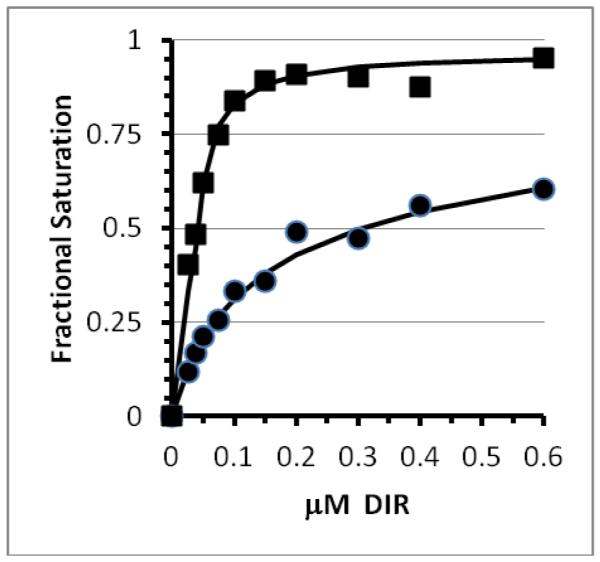

The solution binding properties of three different monomer VL FAPs were studied, Q9, M8VL, and M8VLSL55P. Purified M8VL protein showed an overall dissociation constant of 2.5×10−15 M2 (Figure 1) and a robust ϕf of 71%. The affinity of the M8VLSL55P mutant increased greater than ten-fold to 1.0×10−16 M2 (Figure 1). Due to the nature of the binding reaction, the amount of DIR required to half-saturate the protein (apparent KD) depends on the protein concentration; at a protein concentration of 1nM, the apparent KD values would be 2.5μM for M8VL and 0.1μM for M8VLSL55P, i.e. a ~25 fold increase in affinity. Although the M8VLSL55P mutant protein showed an increase in affinity, the ϕf decreased to 58% (Table 1). The increase in affinity of M8VLSL55P is greater than that observed for the VL domain isolated during affinity maturation of the original VL-VH construct (Q9); the overall dissociation constant of the soluble Q9 protein for DIR is 1.3×10−15 M2. Although the affinity of Q9 for DIR is about 2-fold higher than M8VL, the ϕf is relatively low at 19% (Table 1). There were no significant differences observed in the DIR absorbance spectra of fluoromodules M8VL or Q9VL, despite differences in ϕf (Supporting Information Figure S10).

Figure 1.

Determination of equilibrium dissociation constants for soluble M8VL and M8VLSL55P. Fluorescence data for M8VL (circles) and M8VLSL55P (squares) were fit to scheme 1. Solid lines show the best fit to the data. Error bars for the individual data points are within the size of plotted points. Serial dilutions of DIR was added to 11 nM soluble M8VL or 135nM soluble M8VLSL55P protein in buffer (PBS pH 7.4 with 2mM EDTA, 0.1% w/v Pluronic F-127).

We also analyzed the affinities for DIR and ϕf of the soluble proteins made by M8VL tandem dimers with modified linker lengths. Altering the (G4S) repeats produced soluble proteins with differing affinities and ϕf. The KD values of the M8VL dimer with the (G4S)3, (G4S)4, or (G4S)6 linker was less than 0.1nM and thus it is not possible to compare the KD values for these different constructs. The quantum yield was somewhat dependent on the length of the linker; a value of 38% was found for the (G4S)3 linker, 64% for the (G4S)4 linker, and 55% for the (G4S)6 linker (Table 2 and Supporting Information Figure S11B). A slight drop in the quantum yield for the longer linker may be due to the formation of intermolecular complexes, similar to diabodies or triabodies, but this was not indicated by size exclusion chromatography (Supporting Information S12). The M8VLSL55P dimer with a (G4S)3 linker has a KD of less than 0.1 nM and the lowest ϕf of 14% (Table 2).

Structure of unliganded M8VL and co-crystals of M8VL and M8VLSL55P with DIR

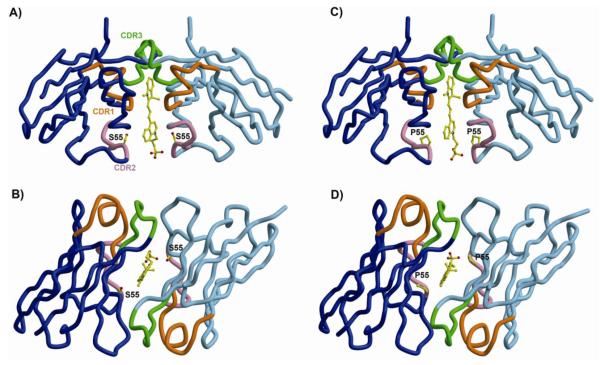

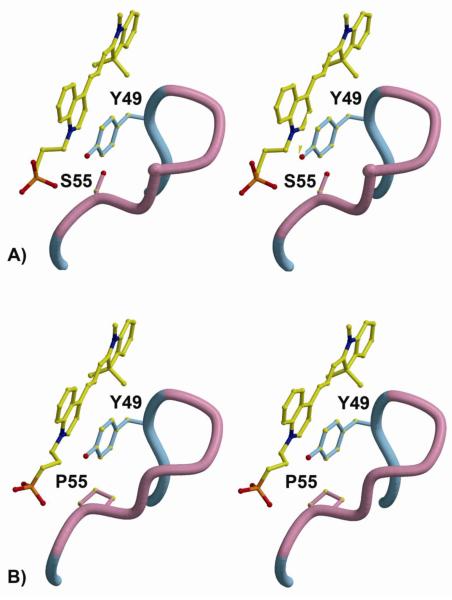

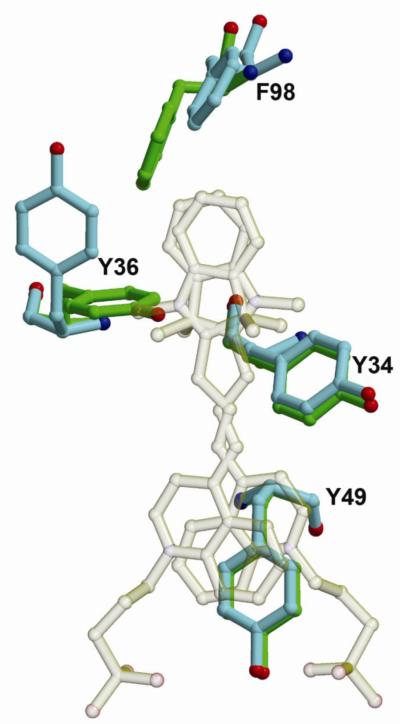

To investigate both the mechanism of DIR fluorescence activation by the M8VL FAPs and to understand the increased affinity and altered fluorescence enhancement of the M8VLSL55P mutant we determined the crystal structure of two of these proteins (Table 3). Crystal structures were obtained for both M8VL and M8VLSL55P in complex with DIR (1.5Å and 1.96Å, resolutions, respectively), as well as the M8VL in the absence of DIR (1.45Å). In all three crystal structures, the M8VL or M8VLSL55P domains adopt a typical Ig-fold. CDR loops from VL domains from all three structures adopt the expected canonical structures, and are classified as: L1=5λ/13A, L2=1/7A, and L3=5λ/11A (45) (46). Both M8VL and M8VLSL55P crystallize as a non-covalent homodimer of VL domains, with the DIR molecule packed tightly at the homodimer interface (Figure 2). In both structures, the VL domains are related by an approximate non-crystallographic two-fold axis, with an angle of ~178° relating the two VL domains in each structure, and the DIR molecules bound on the non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) axis (Figure 3 and Table 4). In the M8VL structure, the DIR occupies two conformations, related by the approximate NCS. In the M8VLSL55P structure, only the indole ring adopts alternate conformations, also related by the NCS two-fold axis (Figure 4). The alternate conformations of the DIR are a crystallization artifact, where the VL dimer binds DIR in one single conformation but the complex then crystallizes in two orientations around NCS 2-fold axis. In the absence of DIR, the M8VL crystallizes with one monomer in the asymmetric unit. This monomer does not closely associate with any symmetry-related neighbors to form a dimer in the crystal (Figure 7a). The homodimeric arrangement seen for M8VL and M8VLSL55P differs strikingly from that seen for a VL-VH dimer in an Fab molecule, and also differs from any VL-VL dimer structures found in the PDB in that the two VL domains are anti-parallel (Supporting Information Figure S13), while still burying the hydrophobic interface that would normally be buried in a VL-VH interaction in a typical antibody. The DIR is buried in a deep pocket and forms contacts primarily with the CDR loops for both M8VL and M8VLSL55P (Figure 2). DIR contact residues are contributed by all CDR loops: TyrL34, AsnL50, ArgL53, Ser/ProL55, SerL56, LeuL89and TrpL96 (Table 4). TyrL34 participates in π-stacking with the conjugated DIR polymethine bridge for both M8VL and M8VLSL55P (Figures 3 and 4), with the centroid of the TyrL34 rings located 5.6-6.1 Å from the plane of the DIR, and angles between TyrL34 and DIR between 31.7°-36.7° (Supporting Information S14). TyrL49 also participates in parallel π-stacking with the DIR quinoline ring for both M8VL and M8VLSL55P (Figures 3 and 4), with the centroid of the TyrL49 rings located 3.6Å −4.0Å from the plane of the DIR, and angles between Tyr and DIR ranging between 5.0°-10.7° (Supporting Information S14). TrpL96 packs perpendicular to the indole ring for both M8VL and M8VLSL55P (Figure 3 and 4), with the centroid of the TrpL96 L ring located 5.5Å-5.7 Å from the plane of the DIR with angles between the TrpL96 and indole ring ranging between 70.3°-78.6° (Supporting Information S14). The DIR molecules are bound with nearly co-planar quinoline and indole rings, with angles between the two ring systems (for the two DIR conformers) in M8VL-DIR of 8.5° and 4.4° and in M8VLSL55P-DIR of 4.2° and 3.0° (Supporting Information S14 and S15).

Figure 2.

Overall topology of M8VL and M8VLSL55P bound to DIR. (A,B) M8VL binds DIR (only one DIR conformation is shown for clarity) sandwiched between two identical VL domains (blue and light blue). The CDR1, CDR2, and CDR3 loops are colored orange, pink, and green, respectively, and are labeled in panel A. The view in (B) is rotated 90° about a horizontal axis. (C,D) M8VLSL55P binds DIR in an almost identical way as M8VL. The SL55P mutation is the only sequence difference between the two structures. The structure figures were generated with Molscript (59) and Bobscript (60).

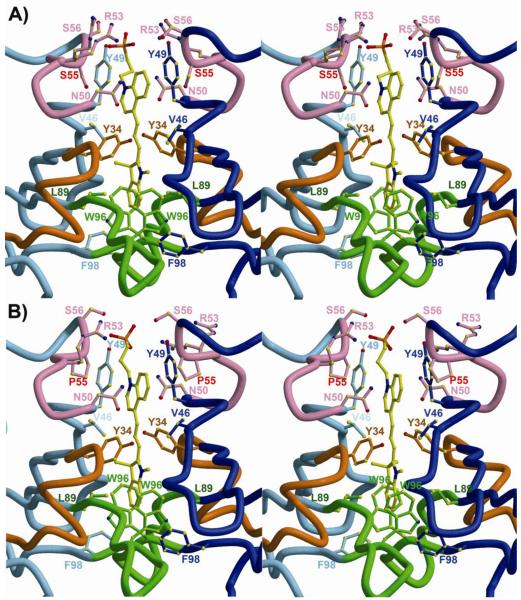

Figure 3.

Environment around DIR ligand in M8VL and M8VLSL55P. The two identical VL domains are shown in blue and light blue. The CDR1, CDR2, and CDR3 loops are colored orange, pink, and green, respectively. (A) Stereoview of the M8VL binding site with contacting residues labeled. Serine 55 is labeled in red. (B) Stereoview of the M8VLSL55P binding site. Proline 55 is labeled in red. Only one DIR conformation is shown for clarity.

Table 4.

Total contacts (van der Waals and hydrogen bonds) from M8VL and M8VLSL55P to DIR (alternate conformation 1/2). Residues in the CDR loops are demoted with asterisks

| Residue | M8VL | M8VLSL55P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Chain A |

Protein Chain B |

Protein Chain A |

Protein Chain B |

|

| *TyrL34 | 5/10 | 8/5 | 6/6 | 7/7 |

| ValL46 | 3/1 | 1/2 | 0/0 | 0/4 |

| TyrL49 | 8/21 | 16/3 | 10/20 | 6/2 |

| *AsnL50 | 0/2 | 1/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| *ArgL53 | 0/8 | 2/0 | 0/3 | 0/0 |

| *Ser/ProL55 | 3/0 | 0/3 | 3/0 | 0/7 |

| *SerL56 | 5/0 | 0/12 | 4/0 | 0/9 |

| *LeuL89 | 2/2 | 2/4 | 4/4 | 2/2 |

| *TrpL96 | 4/5 | 5/3 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| PheL98 | 2/2 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/7 |

| Total | 32/51 | 35/32 | 32/38 | 21/37 |

Contacts calculated with Contacsym (58).

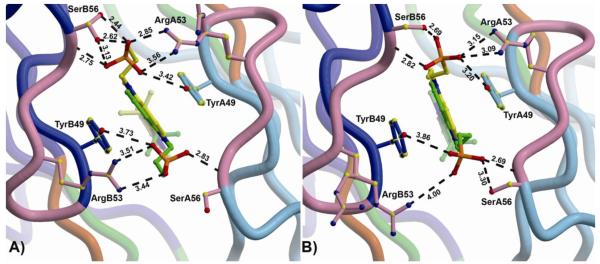

Figure 4.

Sulfonate-protein interactions in M8VL and M8VLSL55P. (A) The interactions between the DIR sulfonate and M8VL show the two orientations of the bound DIR in the crystal structure (green and yellow), and the A (light blue) and B (blue) VL chains. CDR2 is shown in pink. SerB56 and ArgA53 also sample two alternate conformations. (B) The interactions between DIR sulfonates and M8VLSL55P. The indole ring of the DIR is bound in two alternate conformations, and ArgB53 has two alternate conformations. In both M8VL and M8VLSL55P, one sulfonate (top in both of these views) has more interactions with protein than the alternate (bottom) sulfonate. Note that SL55 or PL55 is not shown in either panel.

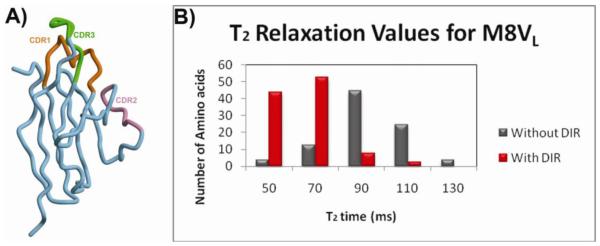

Figure 7.

Crystal structure and solution phase 15N relaxation data for monomeric M8VL. (A) Overall crystal structure of the M8VL in the absence of DIR. This VL domain is monomeric in the crystal structure. (B) The mean NMR T2 relaxation times in the absence (grey bars) or presence (red bars) of DIR.

M8VL and M8VLSL55P complexes with DIR bury a similar amount of molecular surface upon binding DIR, with 573Å2 of protein and 482Å2 of DIR surface buried in the M8VL complex, and 581Å2 of protein and 456Å2 of DIR surface buried in the M8VLSL55P binding pocket (Figure 3). Contacts between DIR and protein are all van der Waals except for hydrogen bonds between protein and the sulfonate groups of the DIR (Figure 4). The M8VLSL55P VL domains do not associate as closely with DIR, with only 53/75 total contacts (van der Waals and hydrogen bonds, to each alternate conformation of DIR) to DIR as opposed to 67/83 contacts seen for the M8VL-DIR complex (Table 4). In particular, the M8VL-DIR TyrL49 has slightly more van der Waals (10) contacts to the DIR quinoline ring than the M8VLSL55P-DIR TyrL49. The effect of the reduced number of van der Waals contacts in the M8VLSL55P-DIR structure compared to the M8VL-DIR on the binding energy was investigated by calculate the differences in DIR binding energies between the two structures using CHARMM. In spite of the reduced number of van der Waals contacts in the M8VLSL55P-DIR structure, the overall contribution of van der Waals interactions to the DIR binding energy is more negative in the M8VLSL55P-DIR at −48.8 kcal/mol; while the van der Waals energy is less negative and thus less favorable at −43.5 kcal/mol for the M8VL-DIR. Consequently, the replacement of serine by proline leads to an additional stabilization of the complex by 5.3 kcal/mol. Superimposition of the M8VL and M8VLSL55P structures reveals no significant conformational changes between the structures, despite a greater than ten-fold decrease in the KD of the M8VLSL55P FAP protein for DIR compared to M8VL. RMSDs for the Cα atoms from residues 1-108 are 0.43Å for A chains, and 0.46Å for the B chains, and 0.52Å for both A and B chains (A and B chains designate the two light chains). When the A chains from each structure are superimposed, it takes only a 1.6° rotation to overlap the B chains. Thus the M8VL and M8VLSL55P structure have similar tertiary and quaternary structures. Three of the four aromatic residues that surround the DIR are slightly closer in the M8VL complex than in the M8VLSL55P complex, with distances between the ring centers of TyrL34A-34B, TyrL49A-49B, TrpL96A-96B, and PheL98A-98Bof 8.6Å, 7.2Å, 8.8Å, and 7.3Å for M8VL and 8.8Å, 7.4Å, 8.6Å, and 7.5Å for M8VLSL55P. This observation is in good agreement with the slightly smaller number of van der Waals contacts to DIR for the M8VLSL55P. ProL55 is close to residue TyrL49 that packs next to the DIR quinoline ring system. The ProL55 residue in the M8VLSL55P packs against TyrL49 in an edge-to face manner, with the plane of the proline approximately 4Å from the edge of TyrL49 (Figure 5) and engages in stronger van der Waals interactions with DIR than the corresponding SerL55 in M8VL.

Figure 5.

Close-up view of the M8VLSL55 L P mutation. (A) Stereoview of M8VL and the interaction between DIR, TyrL49 and SerL55.SerL55 in the M8VL has 6 van der Waals contacts with DIR. (B) Same view of the M8VLSL55P mutant. The proline ring is approximately 4Å from the edge of the TyrL49 ring and makes 10 van der Waals contacts with DIR.

The structure of the unliganded M8VL is very similar to the M8VL-DIR complex. The RMSD for backbone atoms is 0.95 Å, with the largest difference in backbone configuration in the region of PL8, which shows a 4.1 Å displacement between the Cα carbons. Two of the aromatic sidechains that π-stack on the bound DIR, TyrL34 and TyrL49, are superimposable in both structures (Figure 6). In contrast, TyrL36 and PheL98, which also interact with the bound DIR, show large changes in sidechain orientation between the unliganded and M8VL-DIR complex (Figure 6). The X-ray derived structure of the unliganded M8VL appears to reflect the solution conformation of monomeric M8VL. A comparison of 108 HN-HN and HN-aliphatic NOE derived distances show only three violations greater than 0.1 Å and no violations greater than 0.5 Å.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the DIR binding site in unliganded M8VL and the M8VL-DIR complex. The bound DIR is transparent to allow for a better view of the protein side chains. Sidechains from TyrL34, TyrL36, TyrL49 and PheL98 are shown for the unliganded (green) and liganded (light blue) complexes.

NMR data concludes that dimerization of two monomeric M8VL is dependent on DIR

Attempts to measure the oligomeric state of M8VL by size exclusion were unsuccessful due to interaction of the protein with the column (Supporting Information Figure S16). Consequently, solution NMR experiments were performed to determine the 15N T2 relaxation times in the presence and absence of DIR to confirm that M8VL dimerization is not an artifact of crystallization (Figure 7 b). The mean transverse relaxation time (T2) for M8VL in the absence of DIR was found to be ~95.8 ms. Similar values were obtained for M8VLSL55P (data not shown). The mean T2 value for the M8VL in the presence of DIR was 57.15 ms (Supporting Information Figure S17) and a similar decrease was observed for M8VLSL55P (data not shown). To verify the oligomeric state as suggested by T2 relaxation time, we determined the theoretical and experimental global correlation time (τm). The τm for the monomer and homodimer were theoretically determined by HYDRONMR using the appropriate PDB file. The τm for the M8VL in the absence of DIR was 9.36ns compared to the theoretical τm for M8VL in the presence of DIR at 16.38ns. The τm values determined from the experimental relaxation data were 9.90 ns for the M8VL in the absence of DIR and 15.87 ns for the M8VLcomplexed with DIR. These experimental data are consistent with the formation of a dimer in solution when DIR is present. We performed further calculations to confirm the oligomeric state indicated from the mean T2 values using the T1, T2 and heteronuclear NOE data. The theoretically predicted τm for monomeric M8VL of 9.36 ns closely matches the experimental τmvalue of 9.90 ns. The experimental τm value for dimeric M8VL using the model-free approach is 12.37 ns. The model-free spectral density function that was used assumes a spherical shape for the molecule, while the actual M8VL structure is more consistent with a prolate ellipsoid with 2:1 axial ratio. The experimental τm value for M8VL-DIR, when adjusted for this shape, is 15.87 ns which is consistent with the predicted value of 16.38ns for the homodimer (47) (48).

Discussion

We have described the structure-function relationship of a novel fluoromodule based on a scFv that selectively binds the environmentally sensitive fluorogen DIR. We were interested in the dramatic fluorescence activation of DIR by the VL domain when separated from the VH domain and how it related to the fluorescence-generating function of these domains. Affinities and ϕf were determined for several tandem homodimers designed to covalently link two VL domains containing differing serine-glycine linker repeats.

Comparison of directed evolution of VH-VLM8 and M8VL FAPs

The directed evolution of the VH-VL M8 produced three distinct families of clones as opposed to the directed evolution of the M8VL that yielded a single clone. The VH-VL M8 provided more genetic material for directed evolution and more variants were isolated, underscoring the utility of the directed evolution approach to select desired protein properties without previous structural information (8). These results also suggest that there are limitations to the usefulness of rational design approaches, which may fail to account for unusual protein conformations, protein-protein interactions or ligand interactions.

The finding that the VH-VL M8 did not activate DIR when purified as a soluble protein led us to speculate that interactions may be occurring between neighboring FAPs on the surface of the yeast cell. We suggest that the tight affinity of yeast surface displayed VH-VL M8 for DIR is due primarily to the proximity of two nearby VL domains as a result of the pPNL6 yeast surface display system. This proximity would allow two nearby VL domains from two VH-VL chains to readily dimerize after addition of DIR, as the yeast cell surface is highly studded with expressed scFv (49) (50). Homodimerization of VL domains occurs in additional VL domains that bind the fluorogen Malachite green (personal communication Christopher Szent-Gyorgyi).

The two directed evolution approaches indicate that yeast surface display favors the dimerization of the M8VL, regardless of the starting FAP, as both monomeric VL domain and covalent VL-VL FAP clones were isolated from the directed evolution of the VH-VL M8. The strong selective pressure of 250pM DIR is likely responsible for the isolation of covalently linked M8VL domains from VH-VL M8 parent. Additionally, three VL clones isolated without associated VH domains from the VH-VL M8 directed evolution contained cysteine substitutions in the flexible linker normally between the VH and VL domains. These cysteine residues might enhance dimerization on the yeast cell surface through the formation of disulfide bonds between the linker regions of nearby VL domains. This hypothesis is difficult to test without disruption of disulfide bonds that anchor the FAP to the yeast cell surface via the linage to the Aga1p and Aga2p proteins on the yeast cell.

It was unexpected that the directed evolution of the M8VL would produce a single clonal population. This result is an indication that the M8VL either required less optimization to increase affinity and ϕf than VH-VL M8, or when displayed as a single light domain, M8VL has more stringent structural requirements. In the latter case, single amino-acid changes in the VL domain have to be accommodated across the VL-VL homodimer to allow the tight interaction of both the protein and dye component of the fluoromodule.

Yeast surface display analysis of two domain FAPs

Two clones isolated from the directed evolution of VH-VL M8 underscore the novel sequence variations that these FAPs can undergo to cause fluorescence enhancement of DIR. The clone VH-VL L9 that resulted from the VH-VL M8 enrichment retained both VH-VL domains, but contained several mutations only in the VH (FH29S, WH36C, AH93V, IH113iT). The increased fluorescence enhancement of this clone could be a result of VL dimer formation that is enhanced by the WH36C mutation. This mutation might allow the formation of a disulfide bridge between neighboring VH domains on the yeast cell surface, facilitating a closer proximity of their connected VL domains. The VL-VL J8 tandem VL dimer isolated from directed evolution of VH-VL M8 covalently links two M8VL domains, resulting in a substantial decrease in KD that is comparable to the synthetically constructed homodimeric M8VL(G4S)3. It is noteworthy that the VL-VL J8 also contains residue insertions prior to the G4S linker region that may impart increased affinity or ϕf. We hypothesize that residue insertions that originated from the VH domain act to extend the linker length and provide a more suitable dimer structure for the activation of DIR. However, the additional amino-acid mutations present in both light domains of VL-VL J8 might have an additional effect on the affinity of VL-VL J8 for DIR.

The isolation of the VL-VL J8 tandem VL homodimer was novel and unexpected, which led to the investigation of engineered tandem M8VL dimers with different linker lengths. The additional amino acids prior to the linker region in VL-VL J8, as well as measurements from the crystal structure, suggested that a six repeat G4S linker would have the most relaxed structural constraints for DIR. The yeast surface displayed tandem dimers showed no significant difference in DIR affinity regardless of linker length or inclusion of the M8VLSL55P mutation. Thus the linker length between two tandem dimers on yeast surface display does not alter the affinity of the tandem dimers for DIR, however it does alter the affinity of the same soluble proteins. These data indicate that the yeast surface display platform may allow VL-VL interactions of independently displayed VL domains.

Differences in fluorescence activity for yeast surface display versus solution

A consistent observation is that affinities and fluorescence enhancement of fluorgen activating proteins on the surface of yeast can be markedly different than obtained for the same protein free in solution. In particular, KD values for the homodimeric VL-VL proteins in solution were consistently lower than the affinity found on the surface of the yeast cell. For example, the KD values for M8VL-(G4S)3 was 1.7nM on the surface, but substantially less than 1 nM in solution. Similarly, J8 showed a surface KD of ~10 nM, yet the KD in solution was also less than 1 nM. One possible explanation for this effect is that the high density of FAPs on the surface of the protein can result in novel protein-protein interactions. An extreme example of this is the discovery that the soluble VH-VL M8 protein failed to activate DIR while showing a strong fluorescence enhancement on the yeast surface. This result suggests that in solution the VH domain may have a high affinity for the attached VL domain; thus preventing VL-VL homodimerization that likely occurs on the surface of the yeast cell. Alternatively, the soluble VH-VL M8 may contain a favorable affinity for DIR but fails to restrain DIR in an appropriate conformation for fluorescence emission, similar to what is predicted for other fluorogenic cyanine dyes (51).

Relationship between mutations and dimerization on affinity and quantum yield

The soluble Q9 protein has strong affinity for DIR, but a low ϕf of 19%. The numerous mutations isolated in Q9 (QL1R, TL14I,DL30G,QL37R, SL55P, FL62L, SL80P) may be responsible for the decrease in ϕ , although this effect may be combinatorial. Both the M8V L55 f LS P and Q9 contain the SL55P mutation that may cause a decrease in ϕf and potentially improve the respective affinities. However, the Q9 ϕf is significantly lower than either the M8VL or M8VLSL55P ϕf. Thus Q9 and M8VLSL55P suggest that directed evolution of FAP complexes with DIR does not necessarily yield simultaneous increases in both affinity and ϕf. Further characterization of FAPs selected for other fluorogens will determine if decreased ϕf coupled with enhanced affinity can occur among FAPs subjected to directed evolution.

The linking of M8VL and M8VLSL55P by tandem (G4S)3 linkers generated FAPs with high affinity for DIR, as expected by reducing the entropic penalty for bringing two protein domains together with a covalent linkage. Although the affinity increased, the quantum yield decreased for both M8VL and M8VLSL55P. Alternatively, the quantum yields of the extend dimers are larger and thus more efficient at emitting fluorescence than the tandem (G4S)3 M8VL. Thus, the affinity and ϕf do not simultaneously increase for the different linker constructions of the M8VL tandem homodimers. These data taken together indicate that the conformational requirements for increased affinity of the fluoromodule do not produce a robust ϕf.

X-ray crystallography and NMR data support the homodimerization of two M8VL domains in the presence of DIR and elucidate the mechanism for fluoromodule fluorescence generation

Both the genetic and structural data support the conclusion that the M8VL forms a homodimer in the presence of DIR. The crystal structures of both M8V and M8VLSL55P reveal a dimer of VL domains sandwiching the DIR and constraining the rotation of the two DIR heterocycle rings, so that the quinoline and indole rings are essentially planar. This nearly planar orientation may be optimal for fluorescence decay as it allows DIR to emit fluorescence as it relaxes from the excited to the ground state while the heterocycles are fixed around the conjugated polymethine bridge (52).

NMR experiments are consistent with both M8VL and M8VLSL55P forming a homodimer only in the presence of DIR. Based on the canonical scFv interaction between VH and VL domains, it would be expected that the domains would have a low micromolar KD for each other (53); however, even at ~1 millimolar concentrations of M8VL and M8VLSL55P in the NMR experiments, there is no evidence of a strong interaction between light domains. The average transverse relaxation time, T2 for the monomeric M8VL was approximately double that of the M8VL homodimer in the presence of DIR. This result is consistent with the homodimerization of M8VL only in the presence of DIR.

The isolation of functional VL domains that possess strong affinity for small molecule fluorogens is intriguing and shows similarities to previous reports describing Bence-Jones proteins isolated from multiple myeloma patients (54). Bence-Jones proteins are immunoglobulin variable light chains that form homodimers. It has been demonstrated that small molecule haptens in solution penetrate into preformed crystals of Bence-Jones proteins and the haptens interact with the hydrophobic regions formed between two variable light domains (55) (56). Although the FAPs described here are distinct from Bence-Jones proteins as they lack a constant light chain domain, they display low nM affinity for fluorogenic compounds.

The M8VLSL55P displays a greater than ten fold enhancement in affinity for DIR compared to wild type M8VL, despite having fewer van der Waals contacts with DIR (Tables 1 and 4). Calculations indicate that the complex between M8VLSL55P and DIR is stabilized by stronger van der Waals contacts. In the absence of detailed solution phase structural and dynamic data, we cannot conclude precisely how the SL55P mutation increases the affinity for DIR. One hypothesis is that the serine to proline mutation imparts more rigidity to the M8VLSL55P protein and ultimately creates a less flexible dimer binding pocket to retain DIR. This increased protein rigidity may reduce entropic changes during binding, thus modulating the affinity. These interactions will be the focus of future studies to determine the energetics and solution dynamics that underlie the affinity changes of these FAPs with DIR.

Both M8VL and M8VLSL55P significantly enhance the fluorescence of DIR, likely by constraining the angle between the planes of the indole and quinoline groups to less than 10 degrees. Previous theoretical predictions of fluorescence generation for torsionally responsive fluorogens such as thiazole orange indicate that optimal radiative decay occurs when the heterocyclic groups are restricted to a 0-60 degree interplanar angle (51). There is no corresponding model for DIR. However, our data indicate that the ϕf is robust when DIR is held in a nearly planar conformation. The π-stacking interactions between tyrosines in M8VL and M8VLSL55P with DIR may also stabilize the fluorescence signal from DIR based on studies of unsymmetrical cyanine dyes that π-stack during DNA intercalation (6) (57). The structural data suggest that conserved π-stacking interactions with TyrL34 and TyrL49 are important for fluorescence activation of both the M8VL and M8VLSL55P homodimers and will be the focus of future studies.

The ϕf of M8VLSL55P is lower than that of M8V . The M8VLSL55P mutation may contribute additional effects to the fluorescence of DIR that are unrelated to a global increase in protein rigidity. For example, direct interactions between the proline and DIR in solution may only weakly constrain the conformational of DIR, thereby reducing the ϕf. The reduced quantum yield associated with other FAPs, Q9 for example, may be due to restriction of the planer groups in DIR at a greater angle than optimal for fluorescence emission. Finally, FAPs may show reduced quantum yields due to quenching of the DIR in the excited state caused by electron transfer involving nearby redox-active side chains. Further structural studies of other DIR binding FAPs will help to clarify the interactions required for ϕf.

Conclusions

Fluoromodules consisting of a specific fluorescence activating protein and an environmentally sensitive fluorogen demonstrate unique properties such as homodimerization induced by the fluorogen DIR. Experimental data show that DIR fluoresces when it is rigidly held between two immunoglobulin variable light domains that dimerize in the presence of DIR. The structural data suggest that conserved π-stacking interactions with tyrosine residues are important for fluorescence activation of both the M8VL and M8VLSL55P homodimers. M8VLSL55P holds DIR in a potentially less flexible binding pocket compared to that from the M8VL. This change is caused by a single serine to proline mutation that also alters ϕf and affinity. Our results demonstrate the challenge of predicting enhanced FAP fluorescence via mutagenic approaches in the absence of directed evolution. Linker scanning, for example, may provide information on tolerated structural changes to a particular protein, but fail to successfully constrain a fluorogen to produce fluorescence. Furthermore, it is reasonable that even with high resolution crystal structures and subsequent rational design we may not correctly predict the mutations that increase both DIR affinity and ϕf, given that a single mutation in M8VLSL55P enhanced binding but not the ϕf. However, combining detailed structural information with computational or rational design approaches may yield significant improvements in fluorescence quantum yield and affinity. For example, performing targeted mutagenesis on the residues that surround the fluorogen in the binding pocket prior to enrichment procedures might increase the probability of obtaining mutants with improved fluorescence. Such an approach may also include computational modeling of the altered protein in addition to random mutagenesis to enhance the FAP complex.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Yehuda Creeger for assistance with FACS, Andreas Plückthun for the gift of pAK-400 plasmid, Gloria Silva and Nathaniel Shank for DIR, along with Josef Franke and Cheryl Telmer for critical review of the manuscript, students in the HHMI supported summer research institute for preliminary NMR data, Paul Barton for help in designing the synthetic M8VL gene, V. Simplaceanu for help in acquiring the NMR relaxation data and Dr. P.R. Gooley with help with the analysis of the relaxation data.

Abbreviations

- FAP

(fluorogen activating protein)

- DIR

(dimethylindole red)

- KD

(dissociation constant)

- ϕf

(fluorescence quantum yield)

- VH

(immunoglobulin variable heavy domain)

- VL

(immunoglobulin variable light domain)

- GFP

(Green Fluorescence Protein)

- FACS

(fluorescence activated cell sorting)

- CDR

(complementarity determining regions)

- NOE

(nuclear Overhauser effect)

- τm

(global rotational correlation time)

- T2

(transverse relaxation time)

Footnotes

Accession Codes X-ray structure coordinates and structure factors for M8VL, M8VL-DIR, and M8VLSL55P-DIR have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank with codes 3T0V, 3T0W, and 3T0X, respectively.

Supporting Information Available Supporting Information available for sequence information, absorbance spectra and details of crystallography data. This information is free of charge from the ACS website via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

This work was supported by NIH grant U54 RR022241 and Howard Hughes Medical Institute grant 52005865. Portions of this work were carried out at GM/CA CAT at the Advanced Photon Source and the Molecular Biology Consortium at the Advanced Light Source. GM/CA CAT has been funded, in whole or in part, from the National Cancer Institute (Y1-CO-1020) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Y1-GM-1104). Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DE-AC02-06CH1135). The Advanced Light Source is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DE-AC02-05CH11231).

References

- 1.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Science. Vol. 263. New York, N.Y: 1994. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression; pp. 802–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szent-Gyorgyi C, Schmidt BF, Creeger Y, Fisher GW, Zakel KL, Adler S, Fitzpatrick JA, Woolford CA, Yan Q, Vasilev KV, Berget PB, Bruchez MP, Jarvik JW, Waggoner A. Fluorogen-activating single-chain antibodies for imaging cell surface proteins. Nature biotechnology. 2008;26:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nbt1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozhalici-Unal H, Pow CL, Marks SA, Jesper LD, Silva GL, Shank NI, Jones EW, Burnette JM, 3rd, Berget PB, Armitage BA. A rainbow of fluoromodules: a promiscuous scFv protein binds to and activates a diverse set of fluorogenic cyanine dyes. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130:12620–12621. doi: 10.1021/ja805042p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zanotti KJ, Silva GL, Creeger Y, Robertson KL, Waggoner AS, Berget PB, Armitage BA. Blue fluorescent dye-protein complexes based on fluorogenic cyanine dyes and single chain antibody fragments. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:1012–1020. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00444h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shank NI, Zanotti KJ, Lanni F, Berget PB, Armitage BA. Enhanced photostability of genetically encodable fluoromodules based on fluorogenic cyanine dyes and a promiscuous protein partner. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131:12960–12969. doi: 10.1021/ja9016864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee LG, Chen CH, Chiu LA. Thiazole orange: a new dye for reticulocyte analysis. Cytometry. 1986;7:508–517. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990070603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alfthan K, Takkinen K, Sizmann D, Soderlund H, Teeri TT. Properties of a single-chain antibody containing different linker peptides. Protein engineering. 1995;8:725–731. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.7.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colby DW, Kellogg BA, Graff CP, Yeung YA, Swers JS, Wittrup KD. Engineering antibody affinity by yeast surface display. Methods in enzymology. 2004;388:348–358. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)88027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldhaus MJ, Siegel RW, Opresko LK, Coleman JR, Feldhaus JM, Yeung YA, Cochran JR, Heinzelman P, Colby D, Swers J, Graff C, Wiley HS, Wittrup KD. Flow-cytometric isolation of human antibodies from a nonimmune Saccharomyces cerevisiae surface display library. Nature biotechnology. 2003;21:163–170. doi: 10.1038/nbt785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falco CN, Dykstra KM, Yates BP, Berget PB. scFv-based fluorogen activating proteins and variable domain inhibitors as fluorescent biosensor platforms. Biotechnology journal. 2009;4:1328–1336. doi: 10.1002/biot.200900075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chao G, Lau WL, Hackel BJ, Sazinsky SL, Lippow SM, Wittrup KD. Isolating and engineering human antibodies using yeast surface display. Nature protocols. 2006;1:755–768. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boder ET, Midelfort KS, Wittrup KD. Directed evolution of antibody fragments with monovalent femtomolar antigen-binding affinity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:10701–10705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170297297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mack ET, Perez-Castillejos R, Suo Z, Whitesides GM. Exact analysis of ligand-induced dimerization of monomeric receptors. Analytical chemistry. 2008;80:5550–5555. doi: 10.1021/ac800578w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Southwick PL, Ernst LA, Tauriello EW, Parker SR, Mujumdar RB, Mujumdar SR, Clever HA, Waggoner AS. Cyanine dye labeling reagents--carboxymethylindocyanine succinimidyl esters. Cytometry. 1990;11:418–430. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990110313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Studier FW. Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein expression and purification. 2005;41:207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Meth. Enzymol. 1997;276A:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta crystallographica. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winn MD, Murshudov GN, Papiz MZ. Macromolecular TLS refinement in REFMAC at moderate resolutions. Methods in enzymology. 2003;374:300–321. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta crystallographica. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabat EA, Wu TT, Perry HM, Gottesman KS, Foeller C. Sequences of proteins of immunological interest. 5 ed Vol. 1. U.S. Department of health and human services; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansen CL, Skordalakes E, Berger JM, Quake SR. A robust and scalable microfluidic metering method that allows protein crystal growth by free interface diffusion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:16531–16536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262485199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Golovanov AP, Hautbergue GM, Wilson SA, Lian LY. A simple method for improving protein solubility and long-term stability. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:8933–8939. doi: 10.1021/ja049297h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. Journal of biomolecular NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrow NA, Zhang O, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. Characterization of the backbone dynamics of folded and denatured states of an SH3 domain. Biochemistry. 1997;36:2390–2402. doi: 10.1021/bi962548h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson BA. Methods in molecular biology. Vol. 278. Clifton, N.J: 2004. Using NMRView to visualize and analyze the NMR spectra of macromolecules; pp. 313–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.d’Auvergne EJ, Gooley PR. The use of model selection in the model-free analysis of protein dynamics. Journal of biomolecular NMR. 2003;25:25–39. doi: 10.1023/a:1021902006114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.d’Auvergne EJ, Gooley PR. Model-free model elimination: a new step in the model-free dynamic analysis of NMR relaxation data. Journal of biomolecular NMR. 2006;35:117–135. doi: 10.1007/s10858-006-9007-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.d’Auvergne EJ, Gooley PR. Set theory formulation of the model-free problem and the diffusion seeded model-free paradigm. Molecular bioSystems. 2007;3:483–494. doi: 10.1039/b702202f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.d’Auvergne EJ, Gooley PR. Optimisation of NMR dynamic models II. A new methodology for the dual optimisation of the model-free parameters and the Brownian rotational diffusion tensor. Journal of biomolecular NMR. 2008;40:121–133. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9213-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.d’Auvergne EJ, Gooley PR. Optimisation of NMR dynamic models I. Minimisation algorithms and their performance within the model-free and Brownian rotational diffusion spaces. Journal of biomolecular NMR. 2008;40:107–119. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9214-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lipari G, Szabo A. Model-free approach to the interpretation of nuclear magnetic-resonance relaxation in macromolecules II Analysis of experimental results. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1982b;104:4559–4570. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lipari G, Szabo A. Model-free approach to the interpretation of nuclear magnetic-resonance relaxation in macromolecules I Theory and range of validity. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1982a;104:4546–4559. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clore G. Deviations from the simple 2-parameter model-free approach to the interpretation of N-15 nuclear magnetic-relaxation of proteins. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1990b al, e. [Google Scholar]

- 35.de la Torre J. Garcia, Navarro S, Martinez M. C. Lopez, Diaz FG, Cascales J. J. Lopez. HYDRO: a computer program for the prediction of hydrodynamic properties of macromolecules. Biophysical journal. 1994;67:530–531. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80512-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ikura M, Kay LE, Bax A. A novel approach for sequential assignment of 1H, 13C, and 15N spectra of proteins: heteronuclear triple-resonance three-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. Application to calmodulin. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4659–4667. doi: 10.1021/bi00471a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clubb RT, Thanabal V, Wagner G. A new 3D HN(CA)HA experiment for obtaining fingerprint HN-Halpha peaks in 15N- and 13C-labeled proteins. Journal of biomolecular NMR. 1992;2:203–210. doi: 10.1007/BF01875531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hitchens TK, Lukin JA, Zhan Y, McCallum SA, Rule GS. MONTE: An automated Monte Carlo based approach to nuclear magnetic resonance assignment of proteins. Journal of biomolecular NMR. 2003;25:1–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1021975923026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Briercheck DM, Wood TC, Allison TJ, Richardson JP, Rule GS. The NMR structure of the RNA binding domain of E. coli rho factor suggests possible RNA-protein interactions. Nature structural biology. 1998;5:393–399. doi: 10.1038/nsb0598-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brooks BR, Brooks CL, 3rd, Mackerell AD, Jr., Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, Won Y, Archontis G, Bartels C, Boresch S, Caflisch A, Caves L, Cui Q, Dinner AR, Feig M, Fischer S, Gao J, Hodoscek M, Im W, Kuczera K, Lazaridis T, Ma J, Ovchinnikov V, Paci E, Pastor RW, Post CB, Pu JZ, Schaefer M, Tidor B, Venable RM, Woodcock HL, Wu X, Yang W, York DM, Karplus M. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. Journal of computational chemistry. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atwell JL, Breheney KA, Lawrence LJ, McCoy AJ, Kortt AA, Hudson PJ. scFv multimers of the anti-neuraminidase antibody NC10: length of the linker between VH and VL domains dictates precisely the transition between diabodies and triabodies. Protein engineering. 1999;12:597–604. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.7.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albrecht H, Denardo GL, Denardo SJ. Monospecific bivalent scFv-SH: effects of linker length and location of an engineered cysteine on production, antigen binding activity and free SH accessibility. Journal of immunological methods. 2006;310:100–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rakestraw JA, Sazinsky SL, Piatesi A, Antipov E, Wittrup KD. Directed evolution of a secretory leader for the improved expression of heterologous proteins and full-length antibodies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2009;103:1192–1201. doi: 10.1002/bit.22338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shusta EV, Kieke MC, Parke E, Kranz DM, Wittrup KD. Yeast polypeptide fusion surface display levels predict thermal stability and soluble secretion efficiency. Journal of molecular biology. 1999;292:949–956. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Lazikani B, Lesk AM, Chothia C. Standard conformations for the canonical structures of immunoglobulins. Journal of molecular biology. 1997;273:927–948. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin AC, Thornton JM. Structural families in loops of homologous proteins: automatic classification, modelling and application to antibodies. Journal of molecular biology. 1996;263:800–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weber G. Polarization of the fluorescence of macromolecules. II. Fluorescent conjugates of ovalbumin and bovine serum albumin. The Biochemical journal. 1952;51:155–167. doi: 10.1042/bj0510155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lakowicz J. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. (2 ed) 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boder ET, Wittrup KD. Yeast surface display for screening combinatorial polypeptide libraries. Nature biotechnology. 1997;15:553–557. doi: 10.1038/nbt0697-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boder ET, Wittrup KD. Yeast surface display for directed evolution of protein expression, affinity, and stability. Methods in enzymology. 2000;328:430–444. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)28410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Silva GL, Ediz V, Yaron D, Armitage BA. Experimental and computational investigation of unsymmetrical cyanine dyes: understanding torsionally responsive fluorogenic dyes. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:5710–5718. doi: 10.1021/ja070025z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Constantin TP, Silva GL, Robertson KL, Hamilton TP, Fague K, Waggoner AS, Armitage BA. Synthesis of new fluorogenic cyanine dyes and incorporation into RNA fluoromodules. Organic letters. 2008;10:1561–1564. doi: 10.1021/ol702920e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]