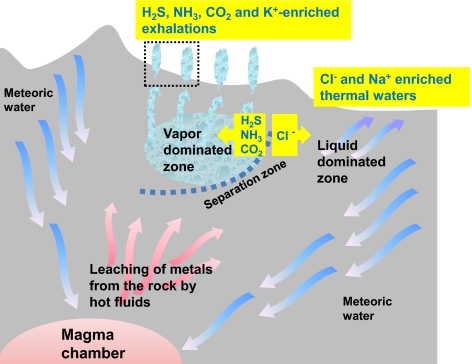

Fig. 1.

A terrestrial geothermal system (scheme based on refs. 52, 53, 62, 138) that is fed mostly by water from rain and snow (meteoric water) which, when it is deep underground, mixes with cation- and anion-enriched magmatic fluids and becomes heated to 300 to 500 °C; such hot fluids can leach diverse ions from the hot rock. Upon heating, the water becomes lighter and, being enriched in metal cations and such anions as Cl−, HS−, and CO32−, ascends toward the surface. At shallower depths, the rising hot water starts to boil because of lower pressure. The vapor phase usually separates from the liquid phase, which leads to the typical zoning (53, 62). The separation is not only physical but also chemical; e.g., whereas Cl− anions mostly stay in the liquid phase, the gaseous compounds, such as CO2, NH3, and H2S, redistribute into vapor. The flow route of the liquid phase and the exact point of its discharge are determined by the crevices within the rock; the ejected fluids are characterized by slightly alkaline pH and high content of chloride and sodium, which both can be traced to the contribution of magmatic waters. The vapor rises upward and spreads within the rock; the subsurface area that is filled by steam and gas is called the vapor-dominated zone. Part of the steam condenses near the surface and is ejected by the thermal springs, and the rest of the steam reaches the surface through fissures of the rock to form fumaroles (i.e., steam vents). Metal cations are carried both by the liquid and by the vapor phases (52, 53), although the K+/Na+ ratio is higher in the vapor phase (Table 2).