Abstract

We conducted a clinical trial to assess adoptive transfer of T cells genetically modified to express an anti-CD19 chimeric Ag receptor (CAR). Our clinical protocol consisted of chemotherapy followed by an infusion of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells and a course of IL-2. Six of the 8 patients treated on our protocol obtained remissions of their advanced, progressive B-cell malignancies. Four of the 8 patients treated on the protocol had long-term depletion of normal polyclonal CD19+ B-lineage cells. Cells containing the anti-CD19 CAR gene were detected in the blood of all patients. Four of the 8 treated patients had prominent elevations in serum levels of the inflammatory cytokines IFNγ and TNF. The severity of acute toxicities experienced by the patients correlated with serum IFNγ and TNF levels. The infused anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells were a possible source of these inflammatory cytokines because we demonstrated peripheral blood T cells that produced TNF and IFNγ ex vivo in a CD19-specific manner after anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusions. Anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells have great promise to improve the treatment of B-cell malignancies because of a potent ability to eradicate CD19+ cells in vivo; however, reversible cytokine-associated toxicities occurred after CAR–transduced T-cell infusions. This trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT00924326.

Introduction

Chimeric Ag receptors (CARs) are fusion proteins that incorporate Ag recognition moieties and T-cell activation domains.1–3 The Ag recognition moieties of CARs are usually variable regions of mAbs.1–3 T cells genetically modified to express CARs acquire the ability to specifically recognize targeted Ags.2–8 CD19 is a protein that is expressed on almost all B-lineage cells.9 Because expression of CD19 is limited to normal and malignant B-lineage cells, CD19 is an attractive target for immunotherapies aimed at B-cell malignancies.9 Many groups have conducted preclinical experiments with T cells expressing anti-CD19 CARs, and these experiments have shown that anti–CD19-CAR–expressing T cells can recognize and destroy target cells in a CD19-specific manner.10–18 The CARs used in these experiments have contained T-cell activation domains from molecules such as CD3ζ and a variety of costimulatory domains such as those from CD28 and 4-1BB.12–17 Murine studies have shown that syngeneic T cells genetically modified to express anti-CD19 CARs can cure lymphoma and cause long-term eradication of normal B cells.19,20 Based on these preclinical experiments, clinical trials of anti-CD19 CARs have been initiated, and some early results from these trials have been reported.21–27 Similar to the murine studies, these early clinical reports have suggested an anti-malignancy effect of T cells expressing anti-CD19 CARs, and Ag-specific eradication of normal B cells has been demonstrated.21,23,24,27

Significant toxicities including hypotension, fevers, and renal insufficiency have occurred after infusions of anti–CD19-CAR–expressing T cells.22–24,27 Three patients with elevations in serum levels of inflammatory cytokines such as IFNγ after anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusions have been reported22–24; however, in one of these cases, the elevation in serum inflammatory cytokines was present before CAR-transduced T cells were infused.22 Determining the causes of elevated cytokine levels after anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusions is not straightforward because only a small number of patients with elevated serum cytokine levels have been reported, and there are other possible causes of elevated serum cytokines such as sepsis.28 Inflammatory cytokines such as IFNγ and TNF (formerly known as TNFα) are produced by anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells in vitro.10,12,15 IFNγ and TNF can cause significant toxicity in humans29–32; however, an association between inflammatory cytokine production by anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells and clinical toxicity has not been demonstrated. A better understanding of the relationship between cytokine production by CAR-transduced T cells and clinical toxicity is necessary to rationally plan future research aimed at increasing the safety of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells.

We are conducting a clinical trial to assess the anti-malignancy efficacy, toxicity, and in vivo persistence of T cells transduced with an anti-CD19 CAR. All of the patients on our clinical trial had advanced, progressive B-cell malignancies that were incurable by any standard treatment except allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Six of the 8 patients treated on our trial obtained objective remissions of their malignancies, and 4 of 8 patients had long-term elimination of CD19+ B-lineage cells. Significant toxicities that correlated with elevations in serum IFNγ and TNF occurred after infusions of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells. In addition, we demonstrated CD19-specific IFNγ and TNF production by T cells from the blood of patients who had received infusions of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells.

Methods

Clinical trial design

The trial was reviewed by the US Food and Drug Administration and the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Institute and allowed to proceed. Patients provided written informed consent before participation in this study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients underwent an apheresis to obtain PBMCs for producing anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells. Cyclophosphamide was administered daily on days −7 and −6 at a dose of 60 mg/kg. On days −5 through −1, patients received 25 mg/m2 fludarabine daily. On day 0, patients received a single infusion of CAR-transduced T cells. Three hours after CAR-transduced T cells were administered, IL-2 was initiated. IL-2 was administered intravenously at a dose of 720 000 international units/kg every 8 hours until toxicity precluded additional doses. Remissions of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or lymphoma were defined according to standard international criteria.33,34

Anti-CD19 CAR retroviral vector design

We previously reported the design and construction of the murine stem cell virus–based splice-gag vector (MSGV)–FMC63-28Z that encoded the anti-CD19 CAR used in our clinical trial.12

Anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cell preparation

Anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells were prepared as described in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) and as previously described.35

In vitro and ex vivo assays

Anti-Fab Ab staining and staining with labeled CD19 protein were used in flow cytometry to detect surface expression of the anti-CD19 CAR as described in the supplemental Methods. ELISAs, intracellular cytokine staining assays (ICCS), and CD107a degranulation assays were performed as described in supplemental Methods and as previously described.12,21 Serum ELISAs were carried out as described in supplemental Methods. Immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry were carried out as detailed in the supplemental Methods and as previously described.21

Real-time qPCR

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was carried out to determine the percentage of peripheral blood mononuclear cells containing the CAR gene as described in supplemental Methods.

Calculation of SOFA scores

The sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score is an established method of quantifying the overall severity of illness.36 The SOFA score includes an assessment of hypotension, the platelet count, and measurements of respiratory, liver, renal, and central nervous system function.36,37 We calculated daily SOFA scores for each patient by using clinical records from the day of CAR-tranduced T-cell infusion and each of the first 10 days after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion.36 For each patient, the sum of the SOFA scores from each day was calculated to give the total SOFA score.36

Results

Production of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells

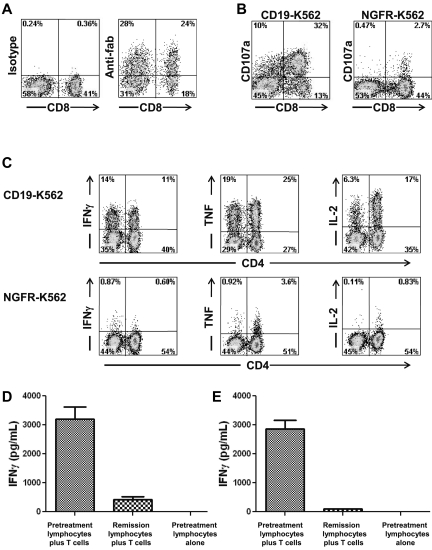

Autologous PBMCs were stimulated with an anti-CD3 mAb and transduced with gammaretroviruses encoding an anti-CD19 CAR (Figure 1A). The anti-CD19 CAR used in our clinical trial contained the variable regions of a murine anti–human-CD19 Ab, a portion of the CD28 molecule, and the signaling domain of the CD3ζ molecule.12 The anti-CD19 CAR could be detected on the surface of transduced T cells by flow cytometry (Figure 2A). For the 8 treated patients, the mean percentage of T cells expressing the anti-CD19 CAR at the time of infusion was 55% (Table 1). Most of the infused CAR-transduced cells were CCR7-negative, CD45RA-negative effector memory cells, but variable numbers of CCR7+, CD45RA-negative central memory cells were also present (Table 2). The CAR-expressing T cells specifically up-regulated CD107a when cultured with CD19-expressing target cells but not when cultured with negative control target cells that lacked CD19 expression (Figure 2B). Up-regulation of CD107a indicated degranulation, which is a prerequisite for perforin-mediated cytotoxicity.38 The CAR-transduced T cells produced IFNγ, TNF, and IL-2 in a CD19-specific manner (Figure 2C, Table 3).

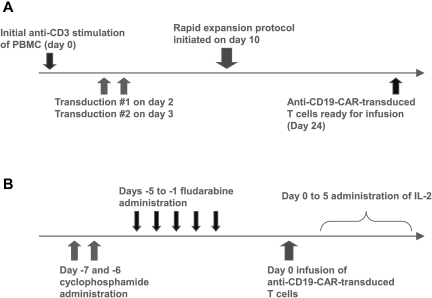

Figure 1.

Anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell production and clinical treatment protocols. (A) PBMCs were stimulated with the anti-CD3 mAb OKT3 on day 0. The cells were transduced with gammaretroviruses encoding the anti-CD19 CAR on days 2 and 3. On day 10, a rapid expansion protocol was started, and the cells were ready for infusion on day 24. (B) Patients received 60 mg/kg cyclophosphamide chemotherapy daily for 2 days. Next, patients received 25 mg/m2 fludarabine chemotherapy daily for 5 days. One day later, the patients received a single infusion of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells. Starting on the same day as the T-cell infusion, the patients received IV IL-2 every 8 hours.

Figure 2.

Anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells produced cytokines in a CD19-specific manner and recognized autologous leukemia cells. (A) Staining with an anti-Fab Ab revealed expression of the anti-CD19 CAR on the surface of T cells that were administered to patient 7. Staining with an isotype control Ab is also shown. Both plots were gated on CD3+ lymphocytes, which made up 99% of the cells in the culture. (B) On the day of infusion, T cells of patient 7 up-regulated CD107a expression after a 4-hour culture with the CD19+ target cell CD19-K562 but not the negative control cell NGFR-K562 that does not express CD19. (C) On the day of infusion, anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells of patient 7 produced IFNγ, TNF, and IL-2 when cultured for 6 hours with the CD19+ target cell CD19-K562 but not the negative control cell NGFR-K562 that does not express CD19. The results shown in panels A through C are representative of the results obtained for all of the patients on the protocol. (D) Anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells of patient 3 were cultured with either autologous pretreatment lymphocytes or autologous remission lymphocytes overnight, and an IFNγ ELISA was performed on the supernatant. Anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells of patient 3 specifically recognized pretreatment lymphocytes but not remission lymphocytes obtained 7 weeks after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion. Sixty-four percent of the pretreatment lymphocytes were CD19+ leukemia cells. The remission lymphocytes contained only 0.1% CD19+ cells. (E) Anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells of patient 6 were cultured with either pretreatment autologous lymphocytes or autologous remission lymphocytes overnight and an IFNγ ELISA was performed on the supernatant. Anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells of patient 6 specifically recognized pretreatment lymphocytes but not remission lymphocytes obtained 2 weeks after CAR–transduced T-cell infusion. Seventy-six percent of the pretreatment lymphocytes were CD19+ leukemia cells. The remission lymphocytes contained only 0.1% CD19+ cells. In both panels D and E, pretreatment lymphocytes cultured alone did not produce detectable quantities of IFNγ.

Table 1.

Patient data

| Patient | Age, y | Malignancy | No. of prior therapies | Total no. of infused cells/kg, ×107 | Percentage of infused cells CAR+ | No. of infused CAR+ cells/kg ×107 | Infused cells CD4/CD8 ratio | Doses of IL-2 administered | Response and time since treatment, mo* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a† | 47 | Follicular lymphoma | 4 | 0.5 | 64 | 0.3 | 29/63 | 8 | PR (7) |

| 1b† | 48 | Follicular lymphoma | 5 | 2.1 | 63 | 1.3 | 19/71 | 10 | PR (18+) |

| 2 | 48 | Follicular lymphoma | 5 | 0.5 | 65 | 0.3 | 23/73 | 9 | NE (died with influenza) |

| 3 | 61 | CLL | 3 | 2.5 | 45 | 1.1 | 35/53 | 2 | CR (15+) |

| 4 | 55 | Splenic marginal zone lymphoma | 3 | 2.0 | 53 | 1.1 | 72/24 | 4 | PR (12) |

| 5 | 54 | CLL | 4 | 0.6 | 50 | 0.3 | 87/12 | 2 | SD (6) |

| 6 | 57 | CLL | 7 | 5.5 | 30 | 1.7 | 37/57 | 1 | PR (7) |

| 7 | 61 | CLL | 4 | 5.4 | 51 | 2.8 | 58/41 | 2 | PR (7+) |

| 8 | 63 | Follicular lymphoma | 7 | 4.2 | 71 | 3.0 | 54/43 | 5 | PR (8+) |

PR indicates partial remission; NE, not evaluable; CR, complete remission; SD, stable disease; and CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Time since treatment is in months; + indicates an ongoing response as of the time of writing. The body surface area of each patient is given in supplemental Table 2.

Patient 1 was treated twice. His first treatment has been previously reported (21).

Table 2.

Memory phenotype of infused anti-CD19 CAR-expressing T cells

| Patient | CD62L | CCR7+CD45RA+ | CCR7+CD45RA− | CCR7−CD45RA− | CCR7−CD45RA+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a* | 21 | 7 | 30 | 53 | 10 |

| 1b* | 20 | 8 | 20 | 55 | 18 |

| 2 | 25 | 5 | 21 | 61 | 13 |

| 3 | 27 | 1 | 8 | 87 | 5 |

| 4 | 35 | 0 | 5 | 90 | 5 |

| 5 | 26 | 3 | 13 | 71 | 13 |

| 6 | 10 | 6 | 27 | 57 | 10 |

| 7 | 4 | 4 | 27 | 60 | 9 |

| 8 | 8 | 1 | 9 | 81 | 8 |

The phenotype of the infused CD19 CAR-expressing T cells was determined by flow cytometry. Values are the percentage of the CAR+ CD3+ cells that expressed the indicated markers.

Patient 1 was treated twice.

Table 3.

Cytokine production by infused cells

| Patient | IFNγ, pg/mL |

TNF, pg/mL |

IL-2, pg/mL |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD19-positive target | CD19-negative target | CD19-positive target | CD19-negative target | CD19-positive target | CD19-negative target | |

| 1* | 8190 | 411 | 448 | < 31 | 1156 | 48 |

| 2 | 9850 | 506 | 6250 | < 31 | 2002 | 139 |

| 3 | 19 000 | 916 | 9312 | < 31 | 1683 | 51 |

| 4 | 27 900 | 944 | 21 895 | < 31 | 2768 | 40 |

| 5 | 36 700 | 734 | 21 515 | < 31 | 2421 | 32 |

| 6 | 14 800 | 130 | 8288 | < 31 | 798 | 44 |

| 7 | 29 300 | 341 | 21 980 | < 31 | 1661 | 36 |

| 8 | 9960 | 240 | 9830 | 73 | 1697 | 46 |

Levels of the indicated cytokines were determined by standard ELISAs after an overnight culture of T cells from the time of infusion with either CD19-positive target cells or CD19-negative target cells. NGFR-K562 cells were used as CD19-negative target cells for all cultures. CD19-K562 cells were used as CD19-positive targets for the cultures preceding the TNF ELISAs. NALM6 cells were used as the CD19-positive target cells for the cultures preceding the IFNγ and IL-2 ELISAs.

Results are from the second treatment of patient 1.

Anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells can specifically recognize autologous leukemia cells

The blood of some of the patients on our trial contained large numbers of CD19+ CLL cells. Access to pretreatment blood samples from these patients allowed us to determine whether anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells could specifically recognize unmanipulated autologous CLL cells. The blood lymphocytes of patient 3 contained 64% CD19+ CLL cells before treatment on our protocol, and the blood lymphocytes of patient 6 contained 76% CD19+ CLL cells before treatment on our protocol. After treatment when the patients were in remission, the blood lymphocytes of both patient 3 and patient 6 contained only 0.1% CD19+ cells. As shown in Figure 2D and E, the anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells from each of these patients produced large amounts of IFNγ when cultured with the pretreatment lymphocytes that were mostly leukemia cells, but the CAR-transduced T cells produced only background levels of IFNγ when cultured with the lymphocytes that were obtained after treatment when the patients were in remission. IFNγ was not produced by the leukemia cells of either patient (data not shown).

Six of the 8 treated patients obtained objective remissions

The 8 patients treated on our protocol had either B-cell lymphoma or CLL (Table 1). The patients all had progressive malignancy at the time of enrollment on our protocol despite a median of 4 prior therapies. All patients treated on our protocol received cyclophosphamide daily for 2 days followed by fludarabine daily for 5 days. One day after the last dose of fludarabine, the patients received a single IV infusion of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells (Figure 1B). Three hours after the CAR-transduced T-cell infusion, a course of IV IL-2 was initiated (Figure 1B). The patients received doses of CAR-expressing T cells that ranged from 0.3 × 107 to 3.0 × 107 CAR+ T cells/kg bodyweight. Patient 1 was treated twice. His first treatment course was previously reported.21 Patient 1 developed progressive CD19+ lymphoma 7 months after his first infusion of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells. After his lymphoma progressed, patient 1 was treated a second time with the same regimen. He remains in a partial remission (PR) 18 months after the second treatment. Patient 2 died 18 days after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion with culture-proven influenza A pneumonia, nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis, and cerebral infarction, so he is not evaluable for lymphoma response. Overall, 6 of the 7 evaluable patients treated on our trial obtained objective remissions (Table 1). Because the patients received chemotherapy with activity against B-cell malignancies immediately before the anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusion, the contribution that the CAR-transduced T cells made to the remissions is unclear.

Patient 3 had a prolonged complete remission and depletion of normal B cells

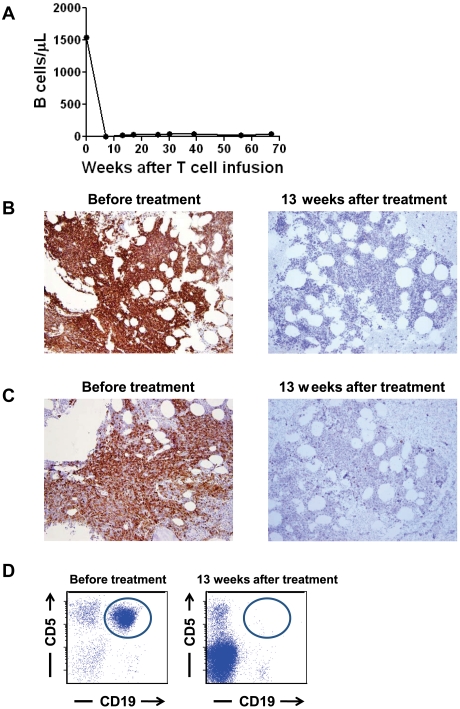

At the time of enrollment on our protocol, patient 3 had progressive CLL after receiving 3 prior therapies. Just before treatment on our protocol, he had a blood B-cell count of 1544 B cells/μL (Figure 3A). Ninety-six percent of the blood B cells were CLL cells. In addition, 50%-60% of his cellular BM was CLL (Figure 3B-C). A prominent clonal leukemia population that expressed the characteristic CD19+ and CD5+ phenotype of CLL was detected by flow cytometry of BM cells before treatment on our protocol (Figure 3D). After treatment, CLL was completely eradicated from the blood of patient 3, and the number of polyclonal blood B cells has stayed at below-normal levels of 17 to 40 B cells/μL for > 15 months (lower limit of the normal 61 B cells/μL; Figure 3A). Patient 3's blood B cells that have returned after treatment were determined to be polyclonal by flow cytometry staining for Ig κ and λ proteins (data not shown). CLL was eliminated from the BM of patient 3 after treatment as shown by BM IHC staining (Figure 3B-C) and by multicolor flow cytometry analysis of the BM cells (Figure 3D). B-lineage cells were nearly absent from the BM, but other hematopoietic cells had recovered (Figure 3B-C). Overall, the cellularity of the BM varied between 20% and 70%. A normal BM cellularity for a 61-year-old patient is ∼ 40%. Patient 3 continues in complete remission > 15 months after treatment on our protocol.

Figure 3.

Normal and malignant B-lineage cells were eliminated from the blood and BM of patient 3. (A) Before treatment, the blood of patient 3 contained an elevated number of B cells, 96% of which were leukemia cells. After treatment, the blood B-cell count has remained below normal and patient 3 has been in complete remission for 67 weeks. B cells were quantitated by flow cytometry staining of CD19+ cells. (B) CD19 IHC staining of the BM of patient 3 is shown before treatment and 13 weeks after treatment. The BM contained large numbers of CD19+ cells before treatment. Thirteen weeks after treatment, CD19+ cells were nearly absent. (C) CD20 IHC staining of the BM of patient 3 is shown before treatment and 13 weeks after treatment. The BM contained large numbers of CD20+ cells before treatment. Thirteen weeks after treatment, CD20+ cells were nearly absent. (D) Flow cytometric results of a BM aspirate from patient 3 are shown. Plots are gated on lymphoid cells by forward and side scatter. A monoclonal population of B cells expressing the characteristic CD19+ and CD5+ phenotype of CLL (circled) was present before treatment but not 13 weeks after treatment.

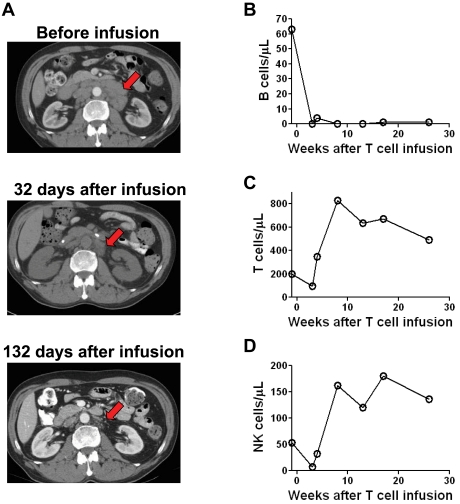

Patient 7 had a substantial reduction in adenopathy after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion

Before enrollment on our protocol, patient 7 had CLL that was progressive despite 4 prior therapies. Extensive regression of adenopathy occurred during the time between a pretreatment computed tomography (CT) scan and a second CT scan that was performed 32 days after treatment (Figure 4A). Regression of the adenopathy continued between day 32 and day 132 after the CAR-transduced T-cell infusion. This continued regression, which occurred > 33 days after the last dose of chemotherapy suggested that the CAR-transduced T cells contributed to the regression of the adenopathy. In accordance with this possibility, anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells persisted in the blood of patient 7 until at least day 132 after infusion (Figure 5B). Because the patient received chemotherapy before the CAR-transduced T cells, an alternative explanation for the decreasing adenopathy between day 32 and 132 after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion is continued resolution of adenopathy because of clearance of leukemia cells that were killed by the chemotherapy.

Figure 4.

Patients receiving infusions of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells had reductions in adenopathy and elimination of normal B cells. CT scans of patient 7 showed extensive adenopathy before treatment. This adenopathy regressed by day 32 after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion (arrow). The enlarged lymph nodes continued to substantially regress between 32 and 132 days after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion. (B) Patient 8 had a normal number of polyclonal blood B cells before treatment. B cells were eliminated from the blood after treatment and had not recovered 26 weeks after anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusion. B cell counts were determined by flow cytometry for CD19 and confirmed by flow cytometry for CD20. In contrast to the B cells, blood T-cell counts (C) and NK-cell counts (D) rapidly recovered after treatment.

Figure 5.

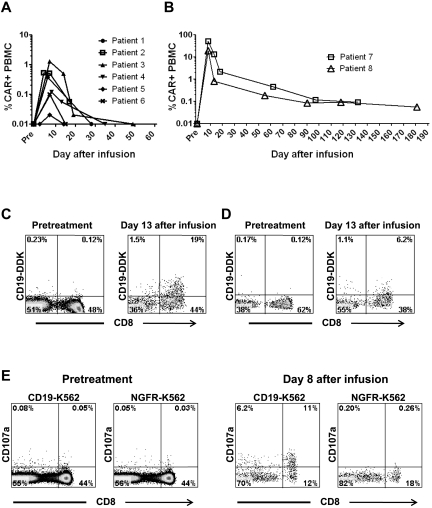

Anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells can be detected in the blood of patients for up to 181 days after infusion. (A) The percentage of total PBMCs that contained the anti-CD19 CAR gene was determined by quantitative PCR. In patients 1 through 6, the peak levels and persistence of cells containing the CAR gene varied. (B) The percentage of total PBMCs from patient 7 and patient 8 that contained the anti-CD19 CAR gene was determined by quantitative PCR. Compared with the other patients, these patients had substantially greater persistence of cells that contained the CAR gene. (C) Anti-CD19 CAR expression was detected ex vivo on PBMCs of patient 7 by flow cytometry staining with labeled CD19 protein (CD19-DDK) 13 days after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion. Only background levels of cells expressing the anti-CD19 CAR were detected before treatment. (D) In patient 8, T cells expressing the anti-CD19 CAR were detected by flow cytometry staining with labeled CD19 protein 13 days after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion. Only background levels of cells expressing the anti-CD19 CAR were detected before treatment. (C-D) The plots are gated on CD3+ lymphocytes. (E) PBMCs from patient 7 were cultured for 4 hours with either CD19+ CD19-K562 cells or NGFR-K562 control cells that do not express CD19. Before treatment, CD107a was not up-regulated on T cells after culture with either CD19-K562 cells or NGFR-K562 cells. In contrast, T cells from 8 days after infusion up-regulated CD107a after a 4-hour culture with CD19-K562 cells but not NGFR-K562 cells. All plots are gated on CD3+ lymphocytes.

Patient 8 had a prolonged specific eradication of normal B cells

Patient 8 had a normal level of polyclonal blood B cells before treatment on our protocol. After treatment, his blood B cells have been eliminated for 26 weeks as of his last follow-up (Figure 4B). The B-cell depletion in patient 8 was specific because blood T cells (Figure 4C) and NK cells (Figure 4D) recovered shortly after treatment. This specific, long-term elimination of normal CD19+ B cells indicates that anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells are destroying cells expressing the targeted CD19 Ag in vivo. Notably, this long-term elimination of B cells cannot be attributed to the chemotherapy that the patient received because we have previously shown that patients receiving the same chemotherapy regimen plus infusions of T cells targeting Ags that are not expressed on B cells recover normal blood B cell numbers in 8 to 19 weeks.21 Overall, we have noted B-cell depletion lasting at least 6 months in 4 of the 8 patients treated on our protocol. As previously reported, patient 1 had a complete eradication of blood and BM B-lineage cells for 36 weeks after his first infusion of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells.21 Nine weeks after his second treatment, patient 1 was found to have a normal number of polyclonal blood B cells. The reason for this recovery of normal B cells is unknown. We have noted prolonged B-cell depletion that lasted at least 6 months in 3 additional patients. Patient 7 had no detectable blood B cells at his last follow-up 7 months after infusion of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells. The prolonged depressions of blood B cell numbers in patient 3 and patient 8 are shown in Figures 3A and 4B, respectively. For all patients, the blood B-cells were quantitated 4 to 5 months after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion (supplemental Table 1).

Varied levels of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells could be detected in the blood of all patients

To quantitate anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells in the blood of patients, we developed a qPCR assay that specifically detected the DNA sequence of the anti-CD19 CAR. Data from these quantitative PCR experiments were expressed as a percentage of total PBMCs that contained the anti-CD19 CAR gene. The persistence of cells containing the CAR gene varied widely, but in patient 1 through patient 6, cells containing the CAR gene could be detected at levels > 0.01% of total PBMCs for < 20 days (Figure 5A). In contrast, patient 7 and patient 8 had high peak percentages and long-term persistence of PBMCs containing the CAR gene (Figure 5B). We confirmed the high levels of CAR-expressing cells in the blood of patient 7 and patient 8 by detecting CAR-expressing T cells with flow cytometry after staining with labeled CD19 protein (Figure 5C and D). We also detected cells containing the CAR gene in the BM of patient 7 and patient 8. As measured by qPCR, 0.03% of the BM cells of patient 7 contained the CAR gene 14 weeks after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion, and 0.13% of the BM cells of patient 8 contained the CAR gene 8 weeks after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion.

T cells that degranulated in a CD19-specific manner were detected in the blood of patient 7 ex vivo

We demonstrated the presence of functional CD19-specific T cells in the blood of patient 7 by detecting T cells that up-regulated CD107a in a CD19-specific manner after anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusion but not before CAR-transduced T-cell infusion (Figure 5E).

Patients experienced significant toxicity that correlated with elevated levels of IFNγ and TNF

As mentioned previously, 4 of the 8 patients on our clinical trial had long-term depletion of normal B cells. In accordance with an eradication of B-lineage cells, all of these 4 patients have developed hypogammaglobulinemia and have subsequently been treated with infusions of IV Igs. B-cell depletion is a manageable form of autoimmunity, and it is not unexpected because autoimmunity has been observed after other immunotherapies.39 Except for B-cell depletion, the most prominent toxicities experienced by patients on our trial included hypotension, fevers, fatigue, renal failure, and obtundation (Table 4). These toxicities generally peaked during the first 8 days after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion and resolved completely over time. Many of the toxicities that were observed in our patients can be caused by cytokines such as IFNγ and TNF. For example, TNF is a potent inducer of hypotension.30,31 IFNγ can cause fever, fatigue, and myalgias.29,32 We have previously reported a patient who received an infusion of T cells transduced with an anti-ERBB2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor-2)–specific CAR without administration of exogenous IL-2.40 This patient developed very high levels of serum inflammatory cytokines shortly after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion and later died.40 The course of this patient demonstrates that CAR-transduced T cells can cause large elevations in serum inflammatory cytokines.40 We have shown that the CAR-transduced T cells administered to our patients could produce IFNγ and TNF in a CD19-specific manner in vitro (Figure 2, Table 3). To determine whether elevated levels of the inflammatory cytokines IFNγ and TNF occurred in our patients after anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusions, we performed ELISAs for IFNγ and TNF on serum samples obtained before treatment and at multiple time-points after treatment (Figure 6). We found that the patients could be divided into 2 groups. One group, which included patients 1, 2, 4, and 5, did not have prominent elevations of serum IFNγ or TNF (Figure 6A and C). The other group, which included patients 3, 6, 7, and 8, had prominent elevations in both IFNγ and TNF during the first 10 days after anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusion (Figure 6B and D). We hypothesized that much of the toxicity that occurred in our patients was because of elevations in inflammatory cytokines such as IFNγ and TNF. To quantify the toxicity experienced by our patients, we calculated SOFA scores for each patient.36,37 The SOFA score is an established method of sequentially quantifying the severity of illness in a patient. The SOFA score is calculated with measurements of blood pressure, respiratory function, renal function, hepatic function, central nervous system function, and the blood platelet count.36,37 The SOFA score increases as the severity of illness increases. We calculated SOFA scores for the day of infusion and each of the first 10 days after infusion for each patient. The sum of the SOFA scores from each day was calculated to give the total SOFA score for each patient. The patients with prominent elevations in serum IFNγ and TNF after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion had a mean total SOFA score of 105.0, and patients without elevations in serum IFNγ and TNF had a mean total SOFA score of 61.5 (P = .016, 2-tailed t test). We tested for an association between the total SOFA scores of each patient and the areas under the curves of each patient's serum IFNγ and TNF levels versus time. The total SOFA scores of each patient correlated with the areas under the curves of each patient's serum IFNγ and serum TNF levels versus time (P = .02 for IFNγ and P = .001 for TNF; Figure 6E-F). Notably, in 3 of the 4 patients with prominent elevations of serum inflammatory cytokines after anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusions, new elevations in serum IFNγ and TNF along with severe toxicity occurred 4 or more days after the patient's last dose of exogenous IL-2. Because toxicities and elevations in serum cytokines associated with exogenous IL-2 usually improve within a few days after IL-2 treatment ceases, the elevated serum inflammatory cytokines and toxicities observed in these patients were probably not because of the exogenous IL-2.41–43 In addition, during the first 12 days after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion, none of the 4 patients with elevated inflammatory cytokines had proven infections that could have caused sepsis, which is associated with elevations in serum inflammatory cytokines.28

Table 4.

Toxicities

| Patient | Toxicities*† |

|---|---|

| 1‡ | Fatigue, herpes zoster with secondary otitis externa 6 months after treatment |

| 2 | Escherichia coli bacteremia, died with influenza pneumonia, dyspnea, hypoxemia, nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis, cerebral infarction, elevated liver enzymes |

| 3 | Hypotension, acute renal failure, hypoxemia, hyperbilirubinemia, capillary leak syndrome |

| 4 | Diarrhea, fatigue |

| 5 | Fever, fatigue, hypotension |

| 6 | Hypotension, capillary leak syndrome, hypoalbuminemia |

| 7 | Obtundation, acute renal failure, hyperbilirubinemia, capillary leak syndrome, anorexia, elevated liver enzymes, electrolyte abnormalities |

| 8 | Hypotension, obtundation, acute renal failure, capillary leak syndrome, headache, pleural effusion, electrolyte abnormalities |

All grade 3 and 4 toxicities by the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 3, are listed.

All patients had pancytopenia with chemotherapy.

Patient 1 was treated twice. Only his second treatment is reported here. The first treatment has been previously reported (21).

Figure 6.

Elevations in serum levels of IFNγ and TNF occurred in some patients after infusions of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells. (A) Patients 1, 2, 4, and 5 did not have prominent elevations of serum IFNγ after cell infusion. (B) Patients 3, 6, 7, and 8 had prominent elevations of serum IFNγ after cell infusion. (C) Patients 1,2,4, and 5 did not have prominent elevations of serum TNF after cell infusion. (D) Patients 3, 6, 7, and 8 had prominent elevations of serum TNF after cell infusion. For panels A through D, day 0 is the day of CAR-transduced T-cell infusion, and serum IFNγ and TNF were determined by standard ELISAs performed on serum samples. (E) The correlation between the total sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scores of each patient and the areas under the curves of each patient's serum IFNγ level (pg/mL)×(days) from the day of CAR-transduced T-cell infusion until day 11 after T-cell infusion is shown. The total SOFA scores and the areas under the curves of serum IFNγ were correlated (Pearson r = 0.8, P = .02). (F) The correlation between the total SOFA scores of each patient and the areas under the curves of each patient's serum TNF level (pg/mL)×(days) from the day before CAR-transduced T-cell infusion until day 12 after T-cell infusion is shown. The total SOFA scores and the areas under the curves of serum TNF were correlated (Pearson r = 0.9, P = .001).

T cells that produced inflammatory cytokines in a CD19-specific manner were detected in the blood of multiple patients after anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusions

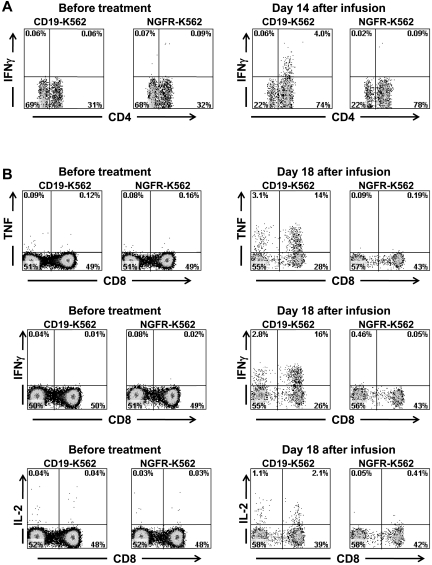

Because CAR-transduced T cells produced IFNγ, TNF, and IL-2 in a CD19-specific manner in vitro (Figure 2C, Table 3), the infused cells might have produced inflammatory cytokines in vivo when the CAR-expressing T cells contacted normal and malignant CD19+ B cells in our patients. We hypothesized that CAR-transduced T cells were a source of the inflammatory cytokines detected in the serum of some the patients on our trial. We obtained PBMCs from patients before and after infusion of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells. The PBMCs were stimulated for 6 hours with CD19+ target cells or negative control target cells that lacked CD19 expression. Before treatment, minimal numbers of T cells that made IFNγ were detected in the blood of patient 3; however, after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion, a population of CD4+ T cells that produced IFNγ in a CD19-specific manner was present (Figure 7A). Similarly, before CAR-transduced T-cell infusion, minimal numbers of T cells producing inflammatory cytokines were detected in the blood of patient 7, but after anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusion, large populations of T cells producing TNF, IFNγ, and IL-2 in a CD19-specific manner were detected after a 6-hour ex vivo culture (Figure 7B). In addition, PBMCs obtained from patient 8 after CAR-transduced T-cell infusion but not before CAR-transduced T-cell infusion contained T cells that produced TNF in a CD19-specific manner (supplemental Figure 1). Production of inflammatory cytokines by CD3-negative blood lymphocytes was not detected in any patient. Ex vivo detection of T cells producing IFNγ or TNF in a CD19-specific manner after anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusions but not before CAR-transduced T-cell infusions suggests that anti-CD19 CAR–transduced T cells were a source of the elevated serum IFNγ and TNF levels in our patients.

Figure 7.

Large numbers of T cells producing cytokines in a CD19-specific manner can be detected in the blood of patients after anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusions. (A) PBMCs were collected from patient 3, 14 days after infusion of CAR-transduced T cells. When the PBMCs were cultured for 6 hours with CD19-K562 cells that expressed CD19, a population of CD4+ cells that produced IFNγ was detected; in contrast, when the PBMCs were cultured with the control cells NGFR-K562 that lack CD19 expression, T cells did not produce IFNγ. PBMCs collected before the anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusion did not produce IFNγ after incubation with either CD19-K562 or NGFR-K562. Plots are all gated on CD3+ lymphocytes. (B) PBMCs were collected from patient 7, 18 days after infusion of CAR-transduced T cells. When the PBMCs were cultured for 6 hours with CD19-K562 cells that expressed CD19, T cells that produced IFNγ, TNF, and IL-2 were detected. When the PBMCs were cultured with the control cells NGFR-K562 that lack CD19 expression, T cells did not produce IFNγ, TNF, or IL-2. PBMCs collected before the anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusion did not produce IFNγ, TNF, or IL-2 after incubation with either CD19-K562 or NGFR-K562. Plots are all gated on CD3+ lymphocytes.

Discussion

We studied 8 patients with advanced, progressive B-cell malignancies on a clinical trial of chemotherapy followed by an infusion of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells and a course of IV IL-2. Six of the 7 evaluable patients studied on our trial obtained strictly defined remissions of their malignancies.33,34 Four of the 6 remissions are ongoing at the time of last follow-up (Table 1). B cells were depleted from the blood of 4 of the 8 patients for at least 6 months after anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusions (Figures 3A, 4B). The duration of normal B-cell depletion in these 4 patients exceeded the duration of the B-cell depletion that occurs because of the chemotherapy regimen that the patients received,21 so we can conclude that the anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells destroyed normal CD19+ B cells in vivo. The depletion of normal CD19+ B cells suggests that the anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells could also destroy malignant CD19+ cells in vivo. While our protocol resulted in clinical remissions and an elimination of the targeted CD19+ B-lineage cells in vivo, toxicities that correlated with elevations in serum levels of the inflammatory cytokines IFNγ and TNF also occurred (Figure 6). We demonstrated CD19-specific production of inflammatory cytokines by T cells from the blood of patients with significant toxicities after receiving infusions of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells (Figure 7). T cells that were capable of producing inflammatory cytokines in a CD19-specific manner could have contacted normal and malignant CD19+ B cells in vivo and produced the cytokines that correlated with clinical toxicity.

Including CD28 costimulatory domains in CARs led to enhanced anti-malignancy efficacy and prolonged persistence of CAR-expressing T cells in murine experiments.16,17 In a recent clinical trial, Savoldo and coworkers have demonstrated an increase in persistence of T cells transduced with an anti-CD19 CAR containing a CD28 moiety compared with T cells transduced with an anti-CD19 CAR without a CD28 moiety in humans.25 Interesting results from 3 patients who were treated with chemotherapy followed by infusions of T cells transduced with an anti-CD19 CAR containing a 4-1BB moiety have recently been reported.23,24 High peak blood levels and long persistence of T cells transduced with the CAR containing the 4-1BB moiety occurred, and 2 of the 3 patients obtained complete remissions of CLL after a combination of chemotherapy plus infusions of anti–CD19-CAR transduced T cells.23,24 Because the number of patients who have been treated with CAR-transduced T cells is still small, the optimal signaling domains to include in CARs have not yet been determined. Optimization of the signaling domains included in CARs is an important area for future study. Using responses to viral Ags is another promising avenue for future studies on enhancing persistence of genetically engineered T cells.5

We have previously demonstrated the critical importance of lymphocyte-depletion before adoptive transfer of syngeneic anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells in mice.20 In this mouse study, all mice that were lymphocyte-depleted with total body irradiation before lymphoma challenge and anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusion survived without any persisting lymphoma and without any normal B cells; in contrast, mice challenged with lymphoma and treated with anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells without lymphocyte depletion all died of lymphoma.20 These results are consistent with other reports that have shown a dramatic enhancement of adoptive T cell therapies of melanoma by lymphocyte depletion before T cell transfer.44,45 In addition, treatment of B-cell malignancies with CAR-transduced T cells in mice was enhanced by elimination of endogenous B cells.46 In accordance with these murine results, a total of 9 patients have been reported who did not receive lymphocyte-depleting therapy before infusions of T cells transduced with anti-CD19 CARs that contained a CD28 domain, and none of these patients had objective remissions of their malignancies.25,27 The evidence that lymphocyte-depletion enhances adoptive T cell therapy plus the known efficacy of chemotherapy and radiotherapy against B-cell malignancies argue for lymphocyte depletion before infusion of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells.

Our trial included a course of IV IL-2 that was administered after the anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells. Exogenous IL-2 can cause toxicities similar to the toxicities that we have observed in our patients41,42; however, the severity of toxicity experienced by patients on our trial did not correlate with the number of doses of IL-2 that the patients received (data not shown). In addition, 3 of the 4 patients on our trial with significant toxicities associated with elevations in serum inflammatory cytokines had severe toxicities and prominent new increases in serum inflammatory cytokines that occurred 4 or more days after IL-2 administration ceased. Because most of the toxicities caused by IV IL-2 rapidly resolve after IL-2 administration ceases, the IV IL-2 was probably not a major cause of the toxicities and elevated cytokine levels in these patients 4 or more days after cessation of IL-2 infusions41–43; however, the IV IL-2 could have contributed to toxicities experiences by our patients during the time of IL-2 administration, and we are amending our protocol to eliminate IL-2 administration. In mice, administration of IL-2 has been shown to enhance production of IFNγ by tumor-specific T cells.47 Therefore, the possibility exists that exogenous IL-2 could enhance production of inflammatory cytokines by CAR-expressing T cells in humans.

A central question for future CAR research is how to minimize toxicity while maximizing anti-malignancy efficacy. We have shown that toxicity correlates with serum inflammatory cytokine levels after CAR-transduced T-cell infusions, so reducing inflammatory cytokine levels in patients receiving infusions of CAR-transduced T cells is a promising approach to decreasing toxicity. Including the signaling domain of 4-1BB rather than the signaling domain of CD28 in CARs has been suggested as a way to decrease cytokine-mediated toxicity.24 Use of 4-1BB in CARs is a promising approach that needs further investigation, but other alterations in signaling chains should also be explored with a goal of decreasing inflammatory cytokines such as TNF while maintaining or enhancing anti-malignancy efficacy. We showed that the infused anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells produced large amounts of IFNγ when cultured in vitro with pretreatment PBMCs that contained large numbers of CD19+ CLL cells; in contrast, the CAR-transduced T cells produced minimal amounts of IFNγ when cultured with remission PBMCs lacking CD19+ cells (Figure 2D and E). In addition, we demonstrated ex vivo CD19-specific production of inflammatory cytokines by T cells from the blood of patients after anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T-cell infusions (Figure 7). These findings suggest that a promising approach to reducing toxicity associated with CD19-specific cytokine production by CAR-transduced T cells is to minimize the number of CD19+ cells encountered by the CAR–transduced cells. This could be accomplished by only administering CAR-transduced T cells to patients with small disease burdens and by treating patients with B-cell depleting mAbs such as the anti-CD20 mAb rituximab before infusions of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells.46,48 Another possible way to reduce acute toxicities after CAR-transduced T-cell infusions is to administer multiple smaller doses of CAR-transduced T cells rather than one large dose of cells. Suicide genes that allow for rapid depletion of genetically modified cells might provide an added measure of safety to CAR-transduced T-cell therapies.49 An additional strategy for reducing toxicity is to administer anti-TNF agents such as etanercept during episodes of severe toxicity.50

Our results demonstrate a powerful ability of anti–CD19-CAR–transduced T cells to eradicate CD19+ cells in humans, but cytokine-associated toxicities occurred after infusions of CAR-transduced T cells. Improvements in adoptive T-cell therapy with CAR-transduced T cells can be expected as investigations into CAR design and clinical application of CAR-transduced T cells continue. Adoptive transfer of genetically modified Ag-specific T cells has great potential to become an important part of the treatment of B-cell malignancies in the near future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Susan Schwarz, Colin Gross, Marcos Garcia, Adriana Byrnes, and all of the Surgery Branch Immunotherapy Fellows for their important contributions to this work.

This work was supported by intramural funding of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Authorship

Contribution: J.N.K. and S.A.R. designed the trial; J.N.K., M.E.D., S.A.F., I.M., M.S.-S., L.D., and R.C. conducted experiments; J.N.K., W.H.W., D.E.S., G.Q.P., M.S.H., R.M.S., J.C.Y., U.S.K., and D.-A.N.N. provided patient care; J.N.K. wrote the manuscript; and M.E.D., S.A.F., D.E.S., J.C.Y., U.S.K., R.A.M., C.L., and S.A.R. edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: James N. Kochenderfer, National Institutes of Health, 10 Center Dr, CRC Rm 3-3330, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: kochendj@mail.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Eshhar Z, Waks T, Gross G, Schindler DG. Specific activation and targeting of cytotoxic lymphocytes through chimeric single chains consisting of antibody-binding domains and the gamma or zeta subunits of the immunoglobulin and T-cell receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(2):720–724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadelain M, Brentjens R, Riviere I. The promise and potential pitfalls of chimeric antigen receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21(2):215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kershaw MH, Teng MWL, Smyth MJ, Darcy PK. Supernatural T cells: genetic modification of T cells for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(12):928–940. doi: 10.1038/nri1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner MK, Heslop HE. Adoptive T cell therapy of cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22(2):251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pule MA, Savoldo B, Myers GD, et al. Virus-specific T cells engineered to coexpress tumor-specific receptors: persistence and antitumor activity in individuals with neuroblastoma. Nat Med. 2008;14(11):1264–1270. doi: 10.1038/nm.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Till BG, Jensen MC, Wang J, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy for indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma using genetically modified autologous CD20-specific T cells. Blood. 2008;112(6):2261–2271. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-128843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwu P, Yang JC, Cowherd R, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of T cells redirected with chimeric antibody/T-cell receptor genes. Cancer Res. 1995;55(15):3369–3373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kershaw MH, Westwood JA, Parker LL, et al. A phase I study on adoptive immunotherapy using gene-modified T cells for ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20 pt 1):6106–6115. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uckun FM, Jaszcz W, Ambrus JL, et al. Detailed studies on expression and function of CD19 surface determinant by using B43 monoclonal antibody and the clinical potential of anti-CD19 immunotoxins. Blood. 1988;71(1):13–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper LJ, Topp MS, Serrano LM, et al. T-cell clones can be rendered specific for CD19: toward the selective augmentation of the graft-versus-B-lineage leukemia effect. Blood. 2003;101(4):1637–1644. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brentjens RJ, Latouche JB, Santos E, et al. Eradication of systemic B-cell tumors by genetically targeted human T lymphocytes co-stimulated by CD80 and interleukin-15. Nat Med. 2003;9(3):279–286. doi: 10.1038/nm827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kochenderfer JN, Feldman SA, Zhao Y, et al. Construction and preclinical evaluation of an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J Immunother. 2009;32(7):689–702. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181ac6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossig C, Bar A, Pscherer S, et al. Target antigen expression on a professional antigen-presenting cell induces superior proliferative antitumor T-cell responses via chimeric T-cell receptors. J Immunother. 2006;29(1):21–31. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000175492.28723.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imai C, Mihara K, Andreansky M, et al. Chimeric receptors with 4-1BB signaling capacity provoke potent cytotoxicity against acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2004;18(4):676–684. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milone MC, Fish JD, Carpenito C, et al. Chimeric receptors containing CD137 signal transduction domains mediate enhanced survival of T cells and increased antileukemic efficacy in vivo. Mol Ther. 2009;17(8):1453–1464. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kowolik CM, Topp MS, Gonzalez S, et al. CD28 costimulation provided through a CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor enhances in vivo persistence and antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred T cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(22):10995–11004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brentjens RJ, Santos E, Nikhamin Y, et al. Genetically targeted T cells eradicate systemic acute lymphoblastic leukemia xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(18 pt 1):5426–5435. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheadle EJ, Gilham DE, Thistlethwaite FC, Radford JA, Hawkins RE. Killing of non-Hodgkin lymphoma cells by autologous CD19 engineered T cells. Br J Haematol. 2005;129(3):322–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheadle EJ, Hawkins RE, Batha H, O'Neill AL, Dovedi SJ, Gilham DE. Natural expression of the CD19 antigen impacts the long-term engraftment but not antitumor activity of CD19-specific engineered T cells. J Immunol. 2010;184(4):1885–1896. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kochenderfer JN, Yu Z, Frasheri D, Restifo NP, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive transfer of syngeneic T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor that recognizes murine CD19 can eradicate lymphoma and normal B cells. Blood. 2010;116(19):3875–3886. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-265041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kochenderfer JN, Wilson WH, Janik JE, et al. Eradication of B-lineage cells and regression of lymphoma in a patient treated with autologous T cells genetically engineered to recognize CD19. Blood. 2010;116(20):4099–4102. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brentjens RYR, Bernal Y, Riviere I, Sadelain M. Treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia with genetically targeted autologous T cells: a case report of an unforeseen adverse event in a phase I clinical trial. Mol Ther. 2010;18(4):666–668. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porter DL, Levine BL, Kalos M, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(8):725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalos ML, Levine BL, Porter DL, et al. T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci Trans Med. 2011;3(95):ra73. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savoldo B, Ramos CA, Liu E, et al. CD28 costimulation improves expansion and persistence of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in lymphoma patients. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(5):1822–1826. doi: 10.1172/JCI46110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen MC, Popplewell L, Cooper LJ, et al. Antitransgene rejection responses contribute to attenuated persistence of adoptively transferred CD20/CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor redirected T cells in humans. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(9):1245–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brentjens R, Riviere I, Park JH. Safety and persistence of adoptively transferred autologous CD19-targeted T cells in patients with relapsed or chemotherapy refractory B-cell leukemias. Blood. 2011;118(18):4817–4828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Annane PD, Bellissant PE, Cavaillon JM. Septic shock. Lancet. 2005;365(9453):63–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17667-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foon KA, Sherwin SA, Abrams PG. A phase I trial of recombinant gamma interferon in patients with cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1985;20(3):193–197. doi: 10.1007/BF00205575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schiller JH, Storer BE, Witt PL, et al. Biological and clinical effects of intravenous tumor necrosis factor-alpha administered three times weekly. Cancer Res. 1991;51(6):1651–1658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfeffer K. Biological functions of tumor necrosis factor cytokines and their receptors. Cyt Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14(3-4):185–191. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vadhan-Raj S, Al-Katib A, Bhalla R. Phase I trial of recombinant interferon gamma in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4(2):137–146. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):579–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111(12):5446–5456. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson LA, Morgan RA, Dudley ME, et al. Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood. 2009;114(3):535–546. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lopes Ferreira F, Peres Bota D, Bross A, Mélot C, Vincent JL. Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;286(14):1754–1758. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pandharipande PP, Shintani AK, Hagerman HE, et al. Derivation and validation of Spo2/Fio2 ratio to impute for Pao2/Fio2 ratio in the respiratory component of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(4):1317–1321. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819cefa9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubio V, Stuge TB, Singh N, et al. Ex vivo identification, isolation and analysis of tumor-cytolytic T cells. Nat Med. 2003;9(11):1377–1382. doi: 10.1038/nm942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amos SM, Duong CPM, Westwood JA, et al. Autoimmunity associated with immunotherapy of cancer. Blood. 2011;118(3):499–509. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-325266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morgan RA, Yang JC, Kitano M, Dudley ME, Laurencot CM, Rosenberg SA. Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Mol Ther. 2010;18(4):843–851. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenberg SA, Lotze MT, Muul LM. A progress report on the treatment of 157 patients with advanced cancer using lymphokine-activated killer cells and interleukin-2 or high-dose interleukin-2 alone. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(15):889–897. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704093161501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenberg SA, Lotze MT, Yang JC, et al. Experience with the use of high-dose interleukin-2 in the treatment of 652 cancer patients. Ann Surgy. 1989;210(4):474–485. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198910000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lotze MT, Matory YL, Ettinghausen SE. In vivo administration of purified human interleukin 2. II. Half life, immunologic effects, and expansion of peripheral lymphoid cells in vivo with recombinant IL 2. J Immunol. 1985;135(4):2865–2875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gattinoni L, Finkelstein SE, Klebanoff CA, et al. Removal of homeostatic cytokine sinks by lymphodepletion enhances the efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-specific CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202(7):907–912. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wrzesinski C, Paulos CM, Gattinoni L, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells promote the expansion and function of adoptively transferred antitumor CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(2):492–501. doi: 10.1172/JCI30414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.James SE, Orgun NN, Tedder TF, et al. Antibody-mediated B-cell depletion before adoptive immunotherapy with T cells expressing CD20-specific chimeric T-cell receptors facilitates eradication of leukemia in immunocompetent mice. Blood. 2009;114:5454–5463. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-232967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Overwijk WW, Theoret MR, Finkelstein SE, et al. Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self-reactive CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198(4):569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McLaughlin P, Grillo-Lopez AJ, Link BK, et al. Rituximab chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for relapsed indolent lymphoma: half of patients respond to a four-dose treatment program. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(8):2825–2833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoyos V, Savoldo B, Quintarelli C, et al. Engineering CD19-specific T lymphocytes with interleukin-15 and a suicide gene to enhance their anti-lymphoma/leukemia effects and safety. Leukemia. 2010;24(6):1160–1170. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yanik GA, Ho VT, Levine JE, et al. The impact of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor etanercept on the treatment of idiopathic pneumonia syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2008;112(8):3073–3081. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.