Abstract

Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) is a member of the CC family of cytokines. It has monocyte and lymphocyte chemotactic activity and stimulates histamine release from basophils. MCP-1 is implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases, including asthma. The airway smooth muscle (ASM) layer is thickened in asthma, and the growth factors and cytokines secreted by ASM cells play a role in the inflammatory response of the bronchial wall. Glucocorticoids and β2-agonists are first-line drug treatments for asthma. Little is known about the effect of asthma treatments on MCP-1 production from human ASM cells. Here, we determined the effect of ciclesonide (a glucocorticoid) and formoterol (a β2-agonist) on MCP-1 production from human ASM cells. TNFα and IL-1β induced MCP-1 secretion from human ASM cells. Formoterol had no effect on MCP-1 expression, while ciclesonide significantly inhibited IL-1β- and TNFα-induced MCP-1. Furthermore, ciclesonide inhibited IL-1β- and TNFα-induced MCP-1 mRNA and IL-1β- and TNFα-induced MCP-1 promoter and enhancer luciferase reporters. Western blots showed that ciclesonide had no effect on IκB degradation. Finally, ciclesonide inhibited an NF-κB luciferase reporter. Our data show that ciclesonide inhibits IL-1β- and TNFα-induced MCP-1 production from human ASM cells via a transcriptional mechanism involving inhibition of NF-κB binding.

Keywords: glucocorticoid, nuclear factor-κB, inflammation

monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1 (CCL-2) is a member of the CC family of cytokines. It is a three-exon gene, regulated by a distal enhancer and a proximal promoter region separated by 2.2 kb of DNA (18). The proximal promoter region is just upstream of the transcription start site and contains a GC box that binds Sp1, NF-κB, and nuclear factor (NF)-1 binding sites, in addition to two activator protein (AP)-1 sites. The distal enhancer contains two NF-κB binding sites (3).

MCP-1 has monocyte and lymphocyte chemotactic activity and can stimulate histamine release from basophils (13). It is implicated in a number of inflammatory diseases, including asthma. Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by increased lamina reticularis, smooth muscle cell hyperplasia, airway hyperreactivity, and airway inflammation (15). Staining of asthmatic and nonasthmatic bronchial biopsies shows the presence of MCP-1 in the bronchial epithelium, subepithelial macrophages, blood vessels, and bronchial smooth muscle, with stronger MCP-1 staining in the asthmatic epithelium and subepithelial layer (24). MCP-1 is also present in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from healthy and atopic asthma patients, with higher concentrations in the asthmatic BALF. Furthermore, asthmatic levels of BALF MCP-1 inversely correlate with measures of pulmonary function, namely, forced expiratory volume in 1 s and forced expiratory flow at 50% of forced vital capacity (13). Allergen challenge can further increase BALF MCP-1 levels (12). Serum MCP-1 levels are also increased in asthmatic compared with nonasthmatic samples, and asthmatic levels increase further during an acute asthma attack (4). Expression of MCP-1 in murine lungs coincides with leukocyte infiltration in an ovalbumin model of induced lung allergic inflammation. Blockade of MCP-1 in the ovalbumin model reduces migration of macrophages, monocytes, T lymphocytes, and eosinophils to the lung in response to ovalbumin and the induction of bronchial hyperreactivity (10). MCP-1 blockade also reduces ovalbumin-induced levels of leukotriene B4, PGE2, thromboxane B2, IL-5, and IL-4, suggesting that MCP-1 is involved in B and T cell activation (10). Interestingly, a polymorphism in the enhancer region of the MCP-1 gene is associated with asthma in children (26).

The grossly thickened airway smooth muscle (ASM) is an important cellular source of chemokines and growth factors in asthma (9). Smooth muscle cells are considered to play a central role in orchestration of the inflammatory response within the bronchial wall (6). MCP-1 secretion from human ASM cells was first described in 1998 (28), and since then its regulation by various stimuli has been investigated. IL-1β, TNFα, and endothelin-1 stimulate MCP-1 mRNA production and protein secretion from human ASM cells (16, 25, 28). Pharmacological inhibitor studies suggest that IL-1β-induced MCP-1 expression is dependent on p38 MAPK, JNK kinase, p42/44 ERK, and the transcription factor NF-κB (29). Detailed characterization of endothelin-1-induced MCP-1 expression shows a requirement for p38 and p42/44 MAPK signaling and a transcriptional mechanism involving binding of the AP-1 c-Jun subunit and the NF-κB p65 subunit to the MCP-1 promoter, with little effect on the MCP-1 enhancer (25). The mechanism of TNFα-induced MCP-1 expression in human ASM cells has not been described. However, in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts, TNFα-induced MCP-1 requires a sequential series of events that links the proximal promoter and distal enhancer regions. TNFα induction of NF-κB binding to the distal enhancer recruits the histone acetyl transferase p300/CREB binding protein, which acetylates the distal enhancer- and proximal promoter-associated histones. Proximal histone acetylation allows access for Sp1 binding to the proximal promoter and subsequent transcription (27).

Glucocorticoids and β2-agonists are commonly used for asthma therapy because of their anti-inflammatory and bronchodilatory effects, respectively. The glucocorticoid dexamethasone inhibits cytomix (combination of IL-1β, TNFα, and IFNγ)-induced MCP-1 mRNA and protein secretion (21), while fluticasone inhibits TNFα-induced MCP-1 via an undefined posttranscriptional mechanism (16). The β2-agonist salmeterol has no effect on TNFα-induced MCP-1 expression (16). There is no further information regarding MCP-1 regulation by glucocorticoids or β2-agonists. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of the glucocorticoid ciclesonide and the β2-agonist formoterol on IL-1β- and TNFα-induced MCP-1 expression from human ASM cells. We found that ciclesonide inhibited TNFα- and IL-1β-induced MCP-1 expression, while formoterol had no effect. The ciclesonide effect was mediated via the MCP-1 promoter and enhancer regions and regulation of NF-κB binding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Formoterol fumarate dehydrate, 5-[(p-fluorophenyl)-2-ureido]thiophene-3-carboxamide (TPCA-1), DMEM, l-glutamine, amphotericin B, penicillin, streptomycin, and trypsin-EDTA were purchased from Sigma (Poole, Dorset, UK). Ciclesonide was a gift from Altana Pharma (Konstanz, Germany). Recombinant human IL-1β, recombinant human TNFα, and the DuoSet ELISA development system for human CCL2/MCP-1 were purchased from R & D Systems (Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK). All reagents for the firefly luciferase assay system were obtained from Promega (Southampton, Hampshire, UK). FuGene 6 transfection reagent was purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Lewes, East Sussex, UK). Rainbow-colored protein molecular weight marker, ECL Western blot detection reagent, and Hyperfilm-ECL were obtained from Amersham (Buckinghamshire, UK). Nitrocellulose membrane was purchased from Bio-Rad (Hemel Hemstead, Hertfordshire, UK). Polyclonal goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase was obtained from DakoCytomation (Ely, Cambridge, UK). Phosphorylated IκB-α (Ser32) and IκB-α were purchased from Cell Signaling/New England Biolabs (Hitchin, Hertfordshire, UK). The NucleoSpin RNA II kit was obtained from Fisher Scientific (Loughborough, Leicestershire, UK). Moloney's murine leukemia virus (MMLV) RT, RNase inhibitor, (dT)15 primer, dNTPs, and MMLV RT buffer were purchased from Promega. TaKaRa SYBR Premix Ex Taq was obtained from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland). MB-120L was a kind gift from GlaxoSmithKline.

Cell culture.

Human ASM cells from human tracheas were obtained from postmortem examinations, as previously described (18a). The study was approved by the North Nottinghamshire Research Ethics Committee. Primary normal human ASM cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 4 mM l-glutamine, 2.5 μg/ml amphotericin B, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum in humidified 5% CO2-95% air at 37°C. Cells at passage 6–7 were used for all experiments.

Experimental protocols.

Once fully confluent, the cells were growth-arrested in DMEM serum-free medium and incubated at 37°C for 24 h prior to treatment. Cells were then treated with IL-1β (0–10 ng/ml) or TNFα (0–100 ng/ml) for 24 h in concentration-response experiments. The supernatants were assayed for MCP-1. In inhibitor studies, cells were preincubated for 30 min and then treated for 24 h with IL-1β or TNFα. Vehicle (DMSO) was added to control wells at equivalent concentration (0.1% maximum concentration).

MCP-1 ELISA.

The MCP-1 DuoSet ELISA kit was used to measure MCP-1 concentrations in cell culture supernatants according to the manufacturer's protocol. All cell supernatants were diluted 1:50 or 1:200 in reagent diluent, so that all concentrations were within the standard curve.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription.

Total RNA was isolated using the NucleoSpin RNA II kit following the manufacturer's protocol: 5 μl of RNA was reverse-transcribed in a total volume of 25 μl, including 132 U of MMLV RT, 26.4 U of RNase inhibitor, 0.6 μg of (dT)15 primer, dNTPs at 2 μM, and 1× MMLV RT buffer. The resulting RT products were used for real-time PCR amplification.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Total human MCP-1 expression was determined using the primer sequences 5′-GCTCAGCCAGATGCAAT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTTGTCCAGGTGGTCCATG-3′ (reverse). For GAPDH, which was used as the housekeeping gene, the primers were as follows: 5′-CCACCCATGGCAAAATTCCATG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCTAGACGGCAGGTCAGG-3′ (reverse). For real-time PCR of 1 μl of reverse-transcribed cDNA, TaKaRa SYBR Premix Ex Taq and the Mx3000P quantitative PCR system (Stratagene) were used. Each reaction consisted of 1× SYBR Premix Ex Taq, sense and antisense primers at 0.2 μM, 1 μl of DNA, and water to a final volume of 25 μl. Thermal cycler conditions included incubation at 95°C for 30 s followed by 50 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 15 s. Integration of the fluorescent SYBR Green into the PCR product was monitored after each annealing step. Amplification of one specific product was confirmed by melting curve analysis.

Vectors and transient transfections.

MCP-1 enhancer and promoter vectors consisted of the pGL3-basic plasmid vector containing the wild-type human MCP-1 enhancer or promoter regulatory sequences driving a luciferase reporter gene. The enhancer construct harbors two NF-κB sites and is contained in the region −2802 to −2573 bp relative to the translation start codon. The MCP-1 promoter construct harbors a number of different transcription factor binding sites and contains the proximal section of the wild-type human MCP-1 promoter region −161 to −1 bp relative to the translation start codon. These constructs have been previously described in detail (16, 25). The NF-κB reporter construct 6NFκBtkluc contains six copies of the NF-κB binding site, which is upstream of a minimal thymidine kinase promoter driving a luciferase gene. The NF-κB reporter was a gift from Dr. Robert Newton (University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada).

FuGene 6 transfection reagent was used to carry out all transient transfections according to the manufacturer's protocol. Human ASM cells were seeded out into 24-well plates at 2.5 × 104 cells/ml in DMEM-supplemented medium. At 50–60% confluence, cells were growth-arrested for 8 h in serum-free, antibiotic-free DMEM containing 4 mM l-glutamine. Fresh serum-free, antibiotic-free DMEM containing 4 mM l-glutamine was changed after 8 h, and cells were transfected with 0.4 μg of DNA and 3 μl of FuGene 6 per well. After 16 h of transfection, the cells were pretreated for 30 min with or without drugs and then stimulated for 6 h with IL-1β (10 ng/ml) or TNFα (10 ng/ml). Cells were then lysed, and firefly and Renilla luciferase activity was determined. For data analysis, the firefly values were divided by the Renilla values, and the data are expressed as the ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase activity.

Western blot.

Western blot was performed to assess the phosphorylation of IκB-α in response to TNFα/IL-1β and in the presence of the glucocorticoid ciclesonide. The medium was aspirated, and the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and incubated with phospho-lysis buffer (20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 137 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10% glycerol, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM DTT, and 0.1 U/ml protease inhibitor cocktail). Samples were collected, and protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay. The BSA standard curve was used to convert the values to protein concentrations (μg/ml). Cell protein (30 μg per lane) was subjected to electrophoresis on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and electroblotted to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. After the membrane was blocked [5% milk in Tris-buffered saline + 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST)], it was incubated overnight at 4°C with phosphorylated (Ser32) IκB-α (1:1,000 dilution) or IκB-α (1:1,000 dilution) primary antibody in 5% BSA in 1× TBST. The membrane was washed (1× TBST) and then incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit, 1:2,000 dilution in 5% BSA in 1× TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was incubated with ECL Western blotting detection reagent and exposed to Hyperfilm-ECL. Subsequently, blots were scanned, and densitometry was performed using Adobe Photoshop.

Statistical analysis.

The mean values of replicate wells for MCP-1 and luciferase levels were calculated and expressed as fold increase. Where MCP-1 absolute values are presented (concentration-response experiments), the mean of all the replicates is shown. Each experiment was performed in cells from three different tracheas, each obtained from a different human donor. Three biological replicates were performed per donor cell line. Values are means ± SE. The data from the experiments were subjected to statistical analysis to determine statistical significance using GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Windows (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA). One-way analysis of variance of the raw data followed by a Dunnett's post test was used to compare all groups with unstimulated control. One-way analysis of variance of the raw data followed by a Tukey's post test was used to compare stimulated samples with drug-treated samples. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

TNFα and IL-1β induce MCP-1 protein release.

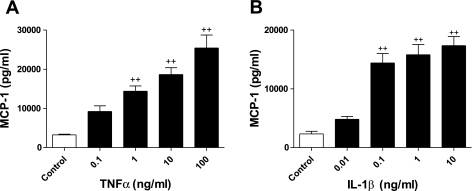

We first studied the effect of TNFα and IL-1β on the release of MCP-1 from human ASM cells. Confluent, growth-arrested human ASM cells were treated for 24 h with increasing concentrations of TNFα (≤100 ng/ml) or IL-1β (≤10 ng/ml). TNFα stimulated MCP-1 release in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1A) above control levels, with a significant increase in MCP-1 at 1–100 ng/ml TNFα. This was also true for IL-1β stimulation, with a significant increase in MCP-1 at 0.1–10 ng/ml IL-1β compared with control (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

TNFα and IL-1β induce monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1 secretion. A and B: human airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells were treated for 24 h with TNFα (0–100 ng/ml) or IL-β (0–10 ng/ml), and MCP-1 secretion was measured by ELISA. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). ++P < 0.01 vs. control.

Differential effects of formoterol and ciclesonide on IL-1β- and TNFα-induced MCP-1.

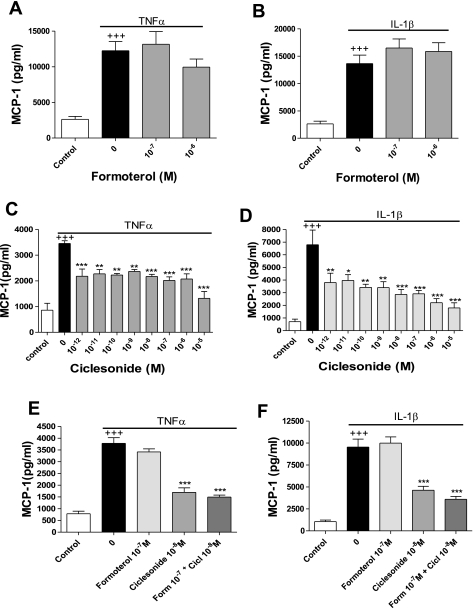

Formoterol is a long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonist. Long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonists are frequently used to treat asthma. Formoterol's effects include bronchodilation and inhibition of mediator release from mast cells and monocytes. Serum-deprived, confluent human ASM cells were preincubated with formoterol and then stimulated for 24 h with TNFα or IL-1β. Formoterol had no effect on TNFα- or IL-1β-induced MCP-1 release (Fig. 2, A and B).

Fig. 2.

Differential effects of ciclesonide and formoterol on TNFα- and IL-1β-induced MCP-1 secretion. A and B: human ASM cells were pretreated for 30 min with formoterol (10−7–10−6 M) and then stimulated for 24 h with TNFα (0.1 ng/ml) or IL-1β (0.1 ng/ml). MCP-1 released into the culture medium was measured by ELISA. Values are means ± SE (n = 4). C and D: human ASM cells were preincubated for 30 min with ciclesonide (10−12–10−5 M) and then stimulated for 24 h with TNFα or IL-1β (0.1 ng/ml). MCP-1 released into the culture medium was measured by ELISA. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). E and F: human ASM cells were pretreated for 30 min with formoterol (Form, 10−7 M) or ciclesonide (Cicl, 10−8 M) or both and then stimulated for 24 h with TNFα (0.1 ng/ml) or IL-1β (0.1 ng/ml). MCP-1 released into the culture medium was measured by ELISA. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). +++P < 0.001 vs. control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. stimulated cells.

Glucocorticoids are a first-line asthma treatment. Their mechanism of action involves inhibitory effects on proinflammatory cytokine production, cell migration, and lymphocyte activation. Ciclesonide is an inhaled glucocorticoid with only mild side effects (20). We tested the effect of ciclesonide on TNFα- and IL-1β-stimulated MCP-1 release from human ASM cells. Serum-deprived human ASM cells were pretreated for 30 min with ciclesonide and then stimulated for 24 h with TNFα or IL-1β. Ciclesonide at 10−12–10−5 M significantly inhibited TNFα-stimulated MCP-1 production (Fig. 2C). IL-1β-stimulated MCP-1 release was also significantly inhibited in a concentration-dependent (10−12–10−5 M) manner (Fig. 2D).

When ciclesonide and formoterol were added in combination, no inhibition beyond that elicited by ciclesonide alone was observed (Fig. 2, E and F).

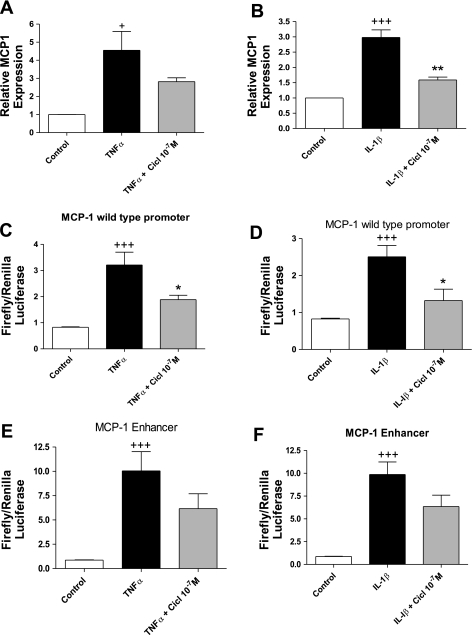

Ciclesonide inhibits MCP-1 mRNA production and MCP-1 promoter and enhancer activity.

To establish whether ciclesonide was acting transcriptionally to inhibit MCP-1, we used quantitative real-time PCR to measure the MCP-1 mRNA level in response to ciclesonide. Confluent serum-starved human ASM cells were preincubated for 30 min with 10−7 M ciclesonide and then stimulated for 8 h with 0.1 ng/ml TNFα or IL-1β. TNFα and IL-1β induced MCP-1 mRNA levels (Fig. 3, A and B). Ciclesonide inhibited TNFα- and IL-1β-induced MCP-1 (Fig. 3, A and B).

Fig. 3.

Ciclesonide inhibits MCP-1 mRNA production and MCP-1 promoter and enhancer activity. A and B: human ASM cells were preincubated for 30 min with 10−7 M ciclesonide and then stimulated for 8 h with TNFα (0.1 ng/ml) or IL-1β (0.1 ng/ml). Cells were lysed, RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed, and cDNA levels were determined by quantitative PCR. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). C and D: 50–60% confluent human ASM cells were transfected for 16 h with MCP-1 promoter plasmid (0.4 μg/well), pretreated for 30 min with ciclesonide (10−7 M), and then incubated for 6 h with TNFα (10 ng/ml) or IL-1β (10 ng/ml). Firefly and Renilla luciferase activity was assayed, and the ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase activity was calculated to represent activity of the reporter. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). E and F: 50–60% confluent human ASM cells were transfected for 16 h with MCP-1 enhancer plasmid (0.4 μg/well), pretreated for 30 min with ciclesonide (10−7 M), and then incubated for 6 h with TNFα (10 ng/ml) or IL-1β (10 ng/ml). Firefly and Renilla luciferase activity was assayed, and the ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase activity was calculated to represent activity of the reporter. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). +P < 0.05, +++P < 0.001 vs. control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. stimulated alone.

Subsequently, we transfected luciferase reporter constructs for the MCP-1 promoter and enhancer into human ASM cells to establish whether ciclesonide affected promoter or enhancer activity. The promoter region construct harbors an NF-κB, an Sp1, and an NF-1 binding site, in addition to two AP-1 sites, while the enhancer region construct harbors 2 NF-κB binding sites. Human ASM cells were transfected with the MCP-1 promoter reporter for 16 h and preincubated for 30 min with 10−7 M ciclesonide before incubation with TNFα (10 ng/ml) or IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 2 h. TNFα and IL-1β significantly increased MCP-1 promoter activity (Fig. 3, C and D). Ciclesonide inhibited MCP-1 promoter activity in the presence of either cytokine.

Human ASM cells were then transfected with the MCP-1 enhancer reporter. When stimulated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) or IL-1β (10 ng/ml), MCP-1 enhancer activity was significantly increased compared with control cells, and this activity was inhibited by nearly twofold with ciclesonide (Fig. 3, E and F).

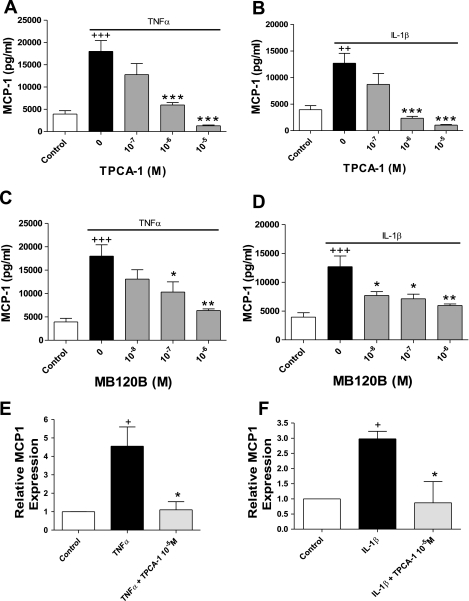

IκB kinase 2 activity is required for TNFα- and IL-1β-induced MCP-1 expression.

Inasmuch as the MCP-1 promoter and enhancer regions contain NF-κB binding sites, we hypothesized that ciclesonide was acting on the NF-κB pathway. Briefly, TNFα and IL-1β signaling can activate IκB kinase 2 (IKK-2). IKK-2 phosphorylates IκB, resulting in its degradation. IκB inhibits NF-κB signaling when they are associated. Initially, we incubated cells with TPCA-1 to investigate whether IKK-2 was required for TNFα- and IL-1β-stimulated MCP-1 production. TPCA-1 is an inhibitor of IKK2 and, thus, inhibits NF-κB signaling by preventing IκB degradation. TPCA-1 dose dependently inhibited TNFα- and IL-1β-stimulated MCP-1 protein release (Fig. 4, A and B). A comparable response was observed with a second IKK2 inhibitor, MB-120B (Fig. 4, C and D). The same effect was seen with TPCA-1 at the mRNA level (Fig. 4, E and F).

Fig. 4.

IκB kinase 2 (IKK-2) activity is required for TNFα- and IL-1β-induced MCP-1 secretion. A–D: human ASM cells were pretreated for 30 min with 5-[(p-fluorophenyl)-2-ureido]thiophene-3-carboxamide (TPCA-1, A and B) or MB-120B and then incubated for 24 h with TNFα (0.1 ng/ml) or IL-1β (0.1 ng/ml). Values are means ± SE (n = 3). E and F: human ASM cells were preincubated for 30 min with 10−5 M TPCA-1 and then stimulated for 8 h with TNFα (0.1 ng/ml) or IL-1β (0.1 ng/ml). Cells were lysed, RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed, and cDNA levels were determined by quantitative PCR. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). +P < 0.05, +++P < 0.001 vs. control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. stimulated alone.

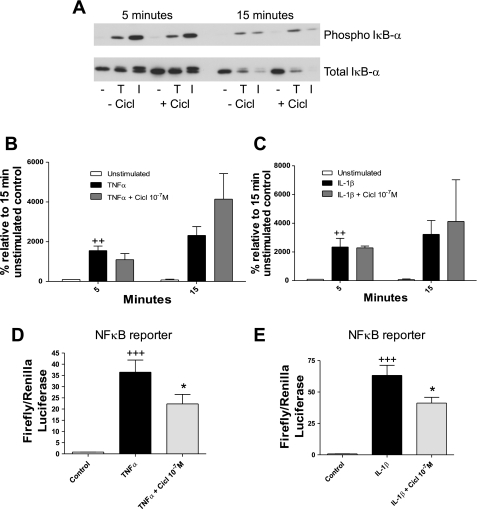

Ciclesonide inhibits binding of NF-κB to its consensus sequence.

Having shown that TNFα and IL-1β require IKK2 activity for MCP-1 production, we investigated whether ciclesonide affected the IKK2-IκB-NF-κB pathway. Initially, we performed Western blots to determine whether ciclesonide was able to prevent IκB degradation. A representative blot is shown in Fig. 5A. TNFα and IL-1β induced phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκB, but this was not inhibited in the presence of ciclesonide (Fig. 5, B and C).

Fig. 5.

Ciclesonide does not affect IκB degradation but does inhibit NF-κB binding to its consensus sequence. A: human ASM cells were preincubated for 30 min with ciclesonide and then incubated for 5 and 15 min with or without TNFα (0.1 ng/ml) or IL-1β (0.1 ng/ml). Cells were lysed and run on a Western blot. Membrane was probed for phosphorylated and total IκB. A representative blot of 3 independent experiments in 3 donor cell lines is shown. B and C: Western blots for phosphorylated and total IκB were scanned, and densitometry was performed for TNFα- and IL-1β-stimulated samples. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). D and E: 50–60% confluent human ASM cells were transfected for 16 h with NF-κB reporter plasmid (0.4 μg/well), pretreated for 30 min with ciclesonide (10−7 M), and then incubated for 6 h with TNFα (10 ng/ml) or IL-1β (10 ng/ml). Firefly and Renilla luciferase activity was assayed, and the ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase activity was calculated to represent activity of the reporter. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001 vs. control. *P < 0.05 vs. stimulated alone.

Finally, using a luciferase reporter containing six copies of the NF-κB binding site upstream of the luciferase gene, we established the effect of ciclesonide on the transcriptional activity of NF-κB. Human ASM cells were transiently transfected with NF-κB reporter constructs, pretreated with ciclesonide (10−7 M), and stimulated for 6 h with TNFα (10 ng/ml) or IL-1β (10 ng/ml). TNFα caused a significant increase (Fig. 5D) in NF-κB reporter activity, which was inhibited by ciclesonide. IL-1β also caused a significant increase (Fig. 5E) in NF-κB reporter activity, which was inhibited by ciclesonide.

Together, these data show that ciclesonide inhibits TNFα- and IL-1β-induced MCP-1 expression by reducing the potential of NF-κB to associate with its binding site.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to demonstrate that the glucocorticoid ciclesonide inhibits TNFα- and IL-1β-induced MCP-1 expression from human ASM cells via a transcriptional mechanism involving the MCP-1 proximal promoter and distal enhancer and the transcription factor NF-κB.

Initially, we confirmed observations made previously, that MCP-1 is secreted basally from human ASM cells and that TNFα and IL-1β can concentration dependently increase MCP-1 in the culture supernatant of these cells. Then we showed that the β2-agonist formoterol had no effect on TNFα- or IL-1β-induced MCP-1 secretion. These findings are in agreement with previous data from our laboratory showing that salmeterol has no effect on TNFα-induced MCP-1 expression (16). Contrary to this, cAMP-elevating agents can inhibit MCP-1 secretion from ASM cells (30). However, β2-agonists are also ineffective against IL-1β-induced IL-8 secretion from ASM cells, while cAMP-elevating agents have an effect, suggesting that β2-agonists act via a different mechanism to direct cAMP elevators (14). We also show that formoterol has no effect when added in combination with the glucocorticoid ciclesonide. However, ciclesonide alone did inhibit TNFα- and IL-1β-induced MCP-1 secretion over a concentration range. Ciclesonide also had a small effect on basal MCP-1 expression (data not shown); however, the effect on stimulated levels was more dramatic and reproducible. This is the first report of any ciclesonide effect on human ASM cells. Pype et al. (21) showed that dexamethasone can inhibit cytomix-induced MCP-1 secretion from human ASM cells. They also showed that dexamethasone reduced cytomix-induced MCP-1 mRNA levels, suggesting that dexamethasone was acting transcriptionally, but no mechanism was established. Conversely, Nie et al. (16) showed that fluticasone inhibited TNFα-induced MCP-1 protein secretion without affecting mRNA levels. Furthermore, fluticasone did not affect TNFα-induced MCP-1 mRNA stability, and Nie et al. concluded that fluticasone was acting via an undefined posttranscriptional mechanism. Dhawan et al. (8) showed that platelet-derived growth factor-induced MCP-1 secretion from arterial smooth muscle cells is inhibited by dexamethasone via glucocorticoid receptor-dependent destabilization of MCP-1 mRNA. Hypoxia-induced MCP-1 is also inhibited by dexamethasone, in part via effects on mRNA stability (7). IL-1β-induced MCP-1 inhibition by any glucocorticoid is not reported. It seems clear that the effects of glucocorticoids on MCP-1 expression are diverse and mediated by mechanisms targeting each step of MCP-1 production.

To determine whether ciclesonide was acting transcriptionally in our system, we measured MCP-1 mRNA levels in response to TNFα, IL-1β, and ciclesonide. In agreement with previous publications (16, 28, 30), TNFα and IL-1β induced MCP-1 mRNA expression. This was inhibited by ciclesonide, suggesting that ciclesonide was acting transcriptionally.

The MCP-1 gene is under the control of a distal enhancer region (−2802 to −2573 bp relative to the translation start codon) and a proximal promoter region (−161 to −1 bp relative to the translation start codon). We used luciferase reporters for these regions and determined that IL-1β and TNFα stimulate the enhancer and promoter reporters. The promoter and enhancer region reporter activities were inhibited by ciclesonide. As the enhancer and promoter regions have NF-κB binding sites in common, we investigated further the role of upstream NF-κB signaling on IL-1β- and TNFα-induced MCP-1 expression. In order for NF-κB to translocate to the nucleus and be transcriptionally active, it must be released from the inhibitory cytoplasmic protein IκB. Release from IκB requires IκB degradation. IKK phosphorylates IκB on two serine residues, which mark the protein for ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome. Thus we used inhibitors of IKK2, namely, TPCA-1 and MB-120B, to determine if upstream NF-κB signaling was involved in IL-1β- and TNFα-induced MCP-1 expression. MCP-1 protein secretion was inhibited by TPCR and MB-120B. MCP-1 mRNA levels were reduced in the presence of TPCA-1. We finally tested whether ciclesonide could affect IκB degradation or NF-κB binding to its consensus binding sequence. We found that ciclesonide had no effect on IκB degradation but did inhibit NF-κB binding. This is contrary to a previous report that pancreatitis-associated ascitic fluid-induced MCP-1 in pancreatic acinar cells is inhibited by dexamethasone via prevention of IκB degradation (22). Prevention of IκB degradation prevents NF-κB translocation and, subsequently, reduces the amount available to bind DNA. Similarly, prednisolone inhibits platelet-derived growth factor-stimulated NF-κB translocation in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (17). In our system, IκB degradation was not changed by ciclesonide, suggesting that the change in NF-κB reporter activity is due to modulation of NF-κB binding as opposed to changes in nuclear NF-κB levels. Interestingly, Amrani et al. (1) showed that dexamethasone cannot inhibit TNFα-induced activation of the NF-κB reporter in ASM cells, suggesting that different glucocorticoids may modulate TNFα signaling differently. Furthermore, Park et al. (19) showed that dexamethasone inhibition of TNFα-induced MCP-1 expression from human glomerular endothelial cells was independent of IκB degradation and NF-κB binding. Studies investigating genes other than MCP-1 have, however, shown effects similar to those seen in the current study. For example, inhibition of TNFα-induced IL-1β expression by dexamethasone in rheumatoid arthritis synovial cells occurs via a change in NF-κB binding ability that is not dependent on IκB degradation or a change in nuclear NF-κB p65 levels (11). There are reports of glucocorticoid-mediated inhibition of NF-κB Ser276 phosphorylation and histone H3 Ser10 phosphorylation (2). Abolishment of NF-κB Ser276 phosphorylation prevents its binding to DNA (23), and phosphorylated (Ser10) histone H3 is associated with open chromatin and active transcription and is suggested as a marker for NF-κB recruitment (5). It is possible that ciclesonide is inhibiting upstream kinase signaling to modify NF-κB or the chromatin environment to regulate MCP-1 expression; however, we failed to see any effect of ciclesonide on NF-κB Ser536 phosphorylation and were unable to detect a signal for NF-κB Ser276 phosphorylation.

In conclusion, we have made the novel observation that inhibition of TNFα- and IL-1β-induced MCP-1 expression from human ASM cells by the glucocorticoid ciclesonide is mediated via a transcriptional mechanism that it not dependent on IκB degradation but, rather, on the ability of TNFα- and IL-1β-induced NF-κB p65 to bind its consensus binding site. The effect of glucocorticoids on MCP-1 expression and NF-κB signaling is diverse, and this study provides new insight into a complex field.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Respiratory Biomedical Research Unit, a Wellcome Trust Programme Grant, and an unrestricted grant from Altana Pharma.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.K.P., R.L.C., and K.D. designed and performed the experiments, R.L.C. drafted the manuscript, A.J.K. initiated and directed the study.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amrani Y, Lazaar AL, Panettieri RA., Jr Up-regulation of ICAM-1 by cytokines in human tracheal smooth muscle cells involves an NF-κB-dependent signaling pathway that is only partially sensitive to dexamethasone. J Immunol 163: 2128–2134, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck IM, Vanden Berghe W, Vermeulen L, Bougarne N, Vander Cruyssen B, Haegeman G, De Bosscher K. Altered subcellular distribution of MSK1 induced by glucocorticoids contributes to NF-κB inhibition. EMBO J 27: 1682–1693, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonello GB, Pham MH, Begum K, Sigala J, Sataranatarajan K, Mummidi S. An evolutionarily conserved TNF-α-responsive enhancer in the far upstream region of human CCL2 locus influences its gene expression. J Immunol 186: 7025–7038, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan CK, Kuo ML, Yeh KW, Ou LS, Chen LC, Yao TC, Huang JL. Sequential evaluation of serum monocyte chemotactic protein 1 among asymptomatic state and acute exacerbation and remission of asthma in children. J Asthma 46: 225–228, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clayton AL, Mahadevan LC. MAP kinase-mediated phosphoacetylation of histone H3 and inducible gene regulation. FEBS Lett 546: 51–58, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clifford RL, Coward WR, Knox AJ, John AE. Transcriptional regulation of inflammatory genes associated with severe asthma. Curr Pharm Des 17: 653–666, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper JA, Jr, Fuller JM, McMinn KM, Culbreth RR. Modulation of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 production by hyperoxia: importance of RNA stability in control of cytokine production. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 18: 521–525, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhawan L, Liu B, Blaxall BC, Taubman MB. A novel role for the glucocorticoid receptor in the regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 mRNA stability. J Biol Chem 282: 10146–10152, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunnill MS, Massarella GR, Anderson JA. A comparison of the quantitative anatomy of the bronchi in normal subjects, in status asthmaticus, in chronic bronchitis, and in emphysema. Thorax 24: 176–179, 1969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalo JA, Lloyd CM, Wen D, Albar JP, Wells TN, Proudfoot A, Martinez AC, Dorf M, Bjerke T, Coyle AJ, Gutierrez-Ramos JC. The coordinated action of CC chemokines in the lung orchestrates allergic inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness. J Exp Med 188: 157–167, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gossye V, Elewaut D, Bougarne N, Bracke D, Van Calenbergh S, Haegeman G, De Bosscher K. Differential mechanism of NF-κB inhibition by two glucocorticoid receptor modulators in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum 60: 3241–3250, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holgate ST, Bodey KS, Janezic A, Frew AJ, Kaplan AP, Teran LM. Release of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MCP-1 into asthmatic airways following endobronchial allergen challenge. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156: 1377–1383, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jahnz-Rozyk KM, Kuna P, Pirozynska E. Monocyte chemotactic and activating factor/monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCAF/MCP-1) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with atopic asthma and chronic bronchitis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 7: 254–259, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaur M, Holden NS, Wilson SM, Sukkar MB, Chung KF, Barnes PJ, Newton R, Giembycz MA. Effect of β2-adrenoceptor agonists and other cAMP-elevating agents on inflammatory gene expression in human ASM cells: a role for protein kinase A. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L505–L514, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kazi AS, Lotfi S, Goncharova EA, Tliba O, Amrani Y, Krymskaya VP, Lazaar AL. Vascular endothelial growth factor-induced secretion of fibronectin is ERK dependent. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 286: L539–L545, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nie M, Corbett L, Knox AJ, Pang L. Differential regulation of chemokine expression by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonists: interactions with glucocorticoids and β2-agonists. J Biol Chem 280: 2550–2561, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogawa A, Firth AL, Yao W, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Prednisolone inhibits PDGF-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L648–L657, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page SH, Wright EK, Jr, Gama L, Clements JE. Regulation of CCL2 expression by an upstream TALE homeodomain protein-binding site that synergizes with the site created by the A-2578G SNP. PLos One 6: e22052, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Pang L, Knox AJ. Effect of IL-1β, TNFα, and IFNγ on induction of COX-2 in cultured human ASM cells. Br J Pharmacol 121: 579–587, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SK, Yang WS, Han NJ, Lee SK, Ahn H, Lee IK, Park JY, Lee KU, Lee JD. Dexamethasone regulates AP-1 to repress TNF-α induced MCP-1 production in human glomerular endothelial cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 312–319, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Postma DS, O'Byrne PM, Pedersen S. Comparison of the effect of low-dose ciclesonide and fixed-dose fluticasone propionate and salmeterol combination on long-term asthma control. Chest 139: 311–318, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pype JL, Dupont LJ, Menten P, Van Coillie E, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J, Chung KF, Demedts MG, Verleden GM. Expression of monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1, MCP-2, and MCP-3 by human airway smooth-muscle cells. Modulation by corticosteroids and T-helper 2 cytokines. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 21: 528–536, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramudo L, Yubero S, Manso MA, Vicente S, De Dios I. Signal transduction of MCP-1 expression induced by pancreatitis-associated ascitic fluid in pancreatic acinar cells. J Cell Mol Med 13: 1314–1320, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reber L, Vermeulen L, Haegeman G, Frossard N. Ser276 phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 by MSK1 controls SCF expression in inflammation. PLos One 4: e4393, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sousa AR, Lane SJ, Nakhosteen JA, Yoshimura T, Lee TH, Poston RN. Increased expression of the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in bronchial tissue from asthmatic subjects. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 10: 142–147, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutcliffe AM, Clarke DL, Bradbury DA, Corbett LM, Patel JA, Knox AJ. Transcriptional regulation of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 release by endothelin-1 in human airway smooth muscle cells involves NF-κB and AP-1. Br J Pharmacol 157: 436–450, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szalai C, Kozma GT, Nagy A, Bojszko A, Krikovszky D, Szabo T, Falus A. Polymorphism in the gene regulatory region of MCP-1 is associated with asthma susceptibility and severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 108: 375–381, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teferedegne B, Green MR, Guo Z, Boss JM. Mechanism of action of a distal NF-κB-dependent enhancer. Mol Cell Biol 26: 5759–5770, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watson ML, Grix SP, Jordan NJ, Place GA, Dodd S, Leithead J, Poll CT, Yoshimura T, Westwick J. Interleukin 8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 production by cultured human airway smooth muscle cells. Cytokine 10: 346–352, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wuyts WA, Vanaudenaerde BM, Dupont LJ, Demedts MG, Verleden GM. Involvement of p38 MAPK, JNK, p42/p44 ERK and NF-κB in IL-1β-induced chemokine release in human airway smooth muscle cells. Respir Med 97: 811–817, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wuyts WA, Vanaudenaerde BM, Dupont LJ, Demedts MG, Verleden GM. Modulation by cAMP of IL-1β-induced eotaxin and MCP-1 expression and release in human airway smooth muscle cells. Eur Respir J 22: 220–226, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]