Abstract

Helminth infections can potentially confer protection against metabolic disorders, possibly through immunomodulation. In this study, the baseline prevalence of lymphatic filariasis (LF) among subjects without (N = 236) and with (N = 217) coronary artery disease (CAD) was examined as part of the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiological Study (CURES). The prevalence of LF was not significantly different between CAD− and CAD+ subjects. The LF antigen load and antibody levels indicated comparable levels of infection and exposure between the groups. Within the CAD group, LF+ and LF− subjects had no significant difference in the intimal medial thickness and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein values. However, LF infection was associated with augmented levels of tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6 among CAD+ subjects. The LF infection had no effect on serum adipocytokine profile. In conclusion, unlike type-2 diabetes, there is no association between the prevalence of LF and CAD and also no evidence of protective immunomodulation of LF infection on CAD in the Asian Indian population.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) and stroke are the largest causes of death worldwide and one of the main contributors to disease burden. Between 1990 and 2020 these diseases are expected to increase by 120% for women and 137% for men in developing countries as compared with 30–60% in developed countries.1 Trends show that there has been a significant decline in the proportion of deaths from infectious diseases (22–16%), whereas mortality from CAD has increased (21–25%) in developing countries, which is largely a reflection of industrialization/globalization.2 Inflammatory changes in the vessel wall plays an important role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis/CAD.3 Although the main underlying mechanism of atherosclerosis/CAD is attributed to a chronic low-grade inflammatory reaction, the spectrum of etiological conditions is far from being fully elucidated. Both viruses and bacteria have been suggested to augment various stages of atherosclerosis development, although a clear pathogenic link between infection and CAD remains debatable.4,5

Helminth infections represent the other extreme of the spectrum wherein, their immunomodulatory effect can in fact dampen inflammation and can potentially confer protection against metabolic diseases.6 Filarial infections are an important group of helminth infections, endemic in South Asian countries where the high-risk ethnic population for CAD resides. The three lymph-dwelling filariae Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, or Brugia timori are the major causative agents of lymphatic filariasis (LF).7 However, there is no data available on the prevalence of LF among people with CAD. Previously, we have reported a decreased prevalence of LF among both type-18 and type-29 diabetic subjects, in South Indians. In this study, the prevalence and influence of LF on CAD was examined as part of an ongoing, epidemiological study in Chennai, Southern India.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement.

Institutional ethical committee approval from the Madras Diabetes Research Foundation Ethics Committee was obtained (Reference no. MDRF-EC/SOC/2009//05) and written informed consent was obtained from all the study subjects.

Study subjects.

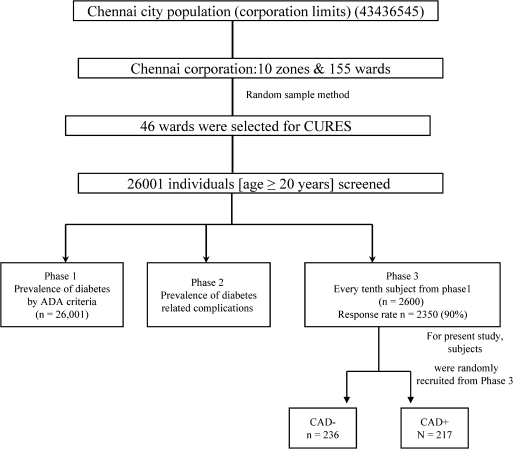

Study subjects were recruited from the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES), an ongoing epidemiological study conducted on a representative population of Chennai, India (Figure 1). The methodology of the study and the prevalence of diabetes and CAD in Chennai have been published elsewhere.10 Briefly, in phase 1 of the urban component of CURES, 26,001 individuals were recruited based on a systematic random sampling technique. Fasting capillary blood glucose was determined using the OneTouch Basic glucometer (Lifescan, Johnson & Johnson, Milpitas, CA) in all subjects. Details of the sampling are described on our website (http://www.drmohansdiabetes.com/bio/WORLD/pages/pages/chennai.html). In phase 2, detailed studies of diabetic complications, including nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy, and cardiomyopathy were performed, and in phase 3, every 10th individual in phase 1 was invited to participate in more detailed studies. As part of the questionnaire, the socio-economic details of the study participants were collected and recorded.

Figure 1.

Flow chart depicting the various stages of sample selection during various phases of Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiological Study (CURES). In phase 1 of the urban component of CURES, 26,001 individuals from 46 wards representing 10 zones of Chennai were recruited based on a systematic random sampling technique and fasting blood glucose was determined. In phase 2, detailed studies of diabetic complications, including nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy were performed, and in phase 3, every 10th individual in phase 1 was invited to participate in more detailed studies, including screening for coronary artery disease. All participants for this study were recruited from phase 3 of CURES.

CAD subjects.

Coronary artery disease was diagnosed based on positive medical history (documented myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and coronary artery bypass graft) and/or ischemic changes on a conventional 12-lead electrocardiogram that included ST-segment depression (Minnesota codes 1-1-1 to 1-1-7) or Q-wave changes (Minnesota codes 4-1 to 4-2).11 For this study, the following groups were randomly selected from phase 3 of CURES, group 1- 236 control subjects without coronary artery disease (CAD−) and group 2- 217 subjects with coronary artery disease (CAD+). The CAD− and CAD+ patients were age and gender matched to avoid the influence of these confounding factors. The filarial status of these individuals was not known at the time of recruitment into the study. Both type-1 and type-2 diabetic subjects were excluded from both groups. All the samples used in this study were collected from 2003 to 2004. None of the study subjects had received any treatment of LF at the time of recruitment (Figure 1).

Sample size calculation.

Initially, 100 CAD− and 100 CAD+ subjects were screened for LF. Out of 100 CAD−, 8 were LF+ (8%) and out of 100 CAD+, 6 were LF+ (6%). Based on these preliminary results, with a confidence interval of 95%, an estimated P value of < 0.05, and a power of 80%, the sample-size estimates were 200 for both CAD− and CAD+ subjects.

Anthropometric and biochemical parameters.

Anthropometric measurements including height, weight, and waist circumference, were obtained using standardized techniques. The body mass index was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Fasting plasma glucose (glucose oxidase-peroxidase method), serum cholesterol (cholesterol oxidase-peroxidase- amidopyrine method), serum triglycerides (glycerol phosphate oxidase-peroxidase-amidopyrine method), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) (direct method-polyethylene glycol-pretreated enzymes), and creatinine (Jaffe's method) were measured using a Hitachi-912 Autoanalyzer (Hitachi, Mannheim, Germany). The intra- and inter-assay coefficient of variation for the biochemical assays ranged between 3.1% and 5.6%. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was estimated by high pressure liquid chromatography using a variant machine (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The intra- and inter-assay coefficient of variation of HbA1c was < 5%. The plasma concentrations of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) were measured by a highly sensitive nephelometric assay using a mono-clonal antibody to CRP coated on polystyrene beads (Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany).12 The intra- and the inter-assay coefficients of variation for hsCRP were 4.2% and 6.8%, respectively, and the detection limit was 0.17 mg/L.

Detection of bancroftian LF.

To quantify the filarial antigen levels and prevalence, sera were analyzed using the W. bancrofti Og4C3 antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Tropbio, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland, Australia) according to the manufacturer's instructions.8,9 A cut-off value of 128 antigen units was considered positive for LF.

Determination of anti-filarial antibody titer.

The serum antibody (IgG and IgG4) titer against Brugia malayi antigen (BmA) was determined by ELISA as described previously.8,9

Measurement of carotid intima-media thickness.

The method used for measurement of carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) has been previously described.11 The IMT of the carotid arteries was determined using a high-resolution B-mode ultrasonography system (Logic 400; GE, Milwaukee, WI) having an electric linear transducer mid-frequency of 7.5 MHz. The images obtained were recorded and photographed. The scanning was done for an average of 20 min. The IMT as defined by Pignoli and Longo13 was measured as the distance from the leading edge of the first echogenic line to the second echogenic line. Six well-defined arterial wall segments were measured in the right carotid system: the near wall and far wall of the proximal 10 mm of the internal carotid artery, the carotid bifurcation beginning at the tip of the flow divider and extending 10 mm below this point, and the arterial segment extending 10 mm below the bifurcation in the common carotid artery. Essential in defining these segments is the identification of a reliable longitudinal marker, which is the carotid flow divider as performed in SECURE (Study to Evaluate Carotid Ultrasound Changes in Patients Treated with Ramipril and Vitamin E).14 This method was standardized at our center and to check quality, the video tapes were sent to Hamilton, Canada, the central laboratory for SECURE.

Determination of serum cytokines.

The levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in the undiluted serum were measured using a Bioplex multiplex cytokine assay system (Bio-Rad). The detection limit for the assays were IL-1β −3 pg/mL, IL-6- 2 pg/mL, TNF-α-5 pg/mL, and IL-10- 2 pg/mL.

Determination of serum adipocytokines.

The levels of adipocytokines (adiponectin, adipsin, leptin, resistin, visfatin, and Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor/PAI-1) in the undiluted serum were measured using a Bioplex multiplex cytokine assay system (Bio-Rad).The detection limit for the adipocytokines were adiponectin 5,244 pg/mL, adipsin 3,380 pg/mL, leptin 2,707 pg/mL, resistin 527 pg/mL, visfatin 8,181 pg/mL, and PAI-1-911 pg/mL.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 15.0.0; Chicago, IL). The prevalence of filarial infections among the different groups was compared by Pearson's Chi-square (χ2) test. The antigenic load and antibody titers and serum cytokines were analyzed by the Mann Whitney U test. The clinical and biochemical characteristics of the study subjects were compared using the Student's t test. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Study population characteristics.

The baseline clinical and biochemical features of the CAD− and CAD+ study subjects are shown in Table 1. Except for hsCRP and IMT, which were higher in the CAD+ group, none of the other parameters reached statistical significance.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of the study subjects*

| Parameters | Control (N = 236) | CAD N = (115) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 51.7 ± 12.2 | 51.5 ± 14.3 | 0.854 |

| Gender (M/F) | 180/107 | 82/31 | 0.079 |

| Body mass index (Kg/m2) | 22.7 ± 4.2 | 22.7 ± 3.9 | 0.886 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm/Hg) | 123.0 ± 21.2 | 124.9 ± 23.0 | 0.931 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm/Hg) | 76.4 ± 11.3 | 76.4 ± 10.9 | 0.990 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 85.2 ± 8.1 | 86.7 ± 9.6 | 0.177 |

| Glycated hemoglobin (%) | 5.50 ± 0.36 | 5.50 ± 0.35 | 0.787 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.84 ± 1.16 | 1.86 ± 1.07 | 0.706 |

| Serum cholesterol (mg/dL) | 188.6 ± 36.6 | 192.8 ± 50.3 | 0.656 |

| Serum triglyceride (mg/dL) | 123.4 ± 60.5 | 117.8 ± 53.4 | 0.459 |

| High-density Lipoprotein (HDL) (mg/dL) | 45.5 ± 10.8 | 45.8 ± 9.5 | 0.648 |

| Low-density Lipoprotein (LDL) (mg/dL) | 118.5 ± 31.4 | 123.3 ± 44.4 | 0.486 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.87 ± 0.18 | 0.97 ± 1.3 | 0.103 |

| Microalbuminuria (mg/dL) | 20.6 ± 44.1 | 12.8 ± 18.9 | 0.543 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) (geo mean) | 1.4 | 3.3 | < 0.001 |

| Carotid intimal medial thickness (IMT) (mm) | 0.71 ± 0.12 | 0.85 ± 0.33 | < 0.001 |

CAD = coronary artery disease; HOMAR-IR = homeostasis model of assessment-insulin resistance; hsCRP = high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Prevalence of LF, circulating filarial antigen levels, and anti-filarial antibody titer among CAD subjects.

The prevalence of LF was found to be 10.4% in the CAD− and 8.7% in CAD+ groups, respectively, and the difference was not significant. To examine more quantitatively the association of CAD and LF, we measured the serum circulating filarial antigen levels among the filarial positive subjects. There was no significant difference in the absolute levels of circulating filarial antigen in the LF-infected individuals, between the CAD−LF+ (geometric mean 1,374 [range: 138–32,768]) and CAD+LF+ (1,378 [193–14,926]) groups. We next quantified the serum anti-filarial antibody levels among the LF-infected subjects. Although the mean immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Geo mean 86.32 [range: 6.3–1,520.0] versus 54.79 [15.17–175.4]) and IgG4 (Geo mean 51.72 [range: 1.25–1878.0] versus 45.29 ([8.96–6926.0]) levels were slightly lower in the CAD+LF+ group, this did not reach statistical significance. No difference in the socio-economic status was noted between the CAD− and CAD+ subjects included in this study (Supplementary Table 1).

Effect of LF on IMT and hsCRP.

The IMT is a good measure of atherosclerosis, whereas hsCRP serves as an inflammatory marker. The IMT and hsCRP values were significantly elevated in the CAD+ group compared with CAD− group (Table 1). However, within the CAD+ group, there was no significant difference in IMT (0.76 [0.5–2.1] versus 0.76 [0.6–1.3]) and hsCRP values (2.29 [0.15–12.0] versus 2.45 [0.16–12.0]) between LF+ and LF− subjects.

Serum cytokine analysis in subjects with CAD and/or LF.

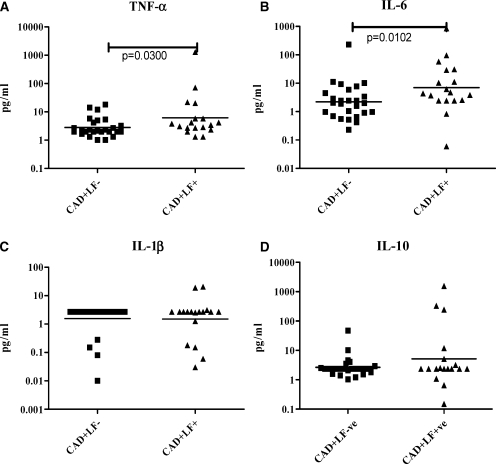

Because pro-inflammatory cytokines are known to be associated with the development of CAD, we next measured the levels of these cytokines in the serum of CAD+LF− and CAD+LF+ subjects. As shown in Figure 2, TNF-α (Geometric mean [GM] [RANGE]- CAD+LF−- 2.8 (1–18) pg/mL and CAD+LF+- 6.8 [1.32–1,290] pg/mL; P = 0.0300) and IL-6 (GM [RANGE]- CAD+LF−- 2.2 [0.23–230] pg/mL and CAD+LF+- 7 [0.06–850] pg/mL; P = 0.0102) levels were significantly elevated in the CAD+LF+ group compared with CAD+LF− group; whereas IL-1β and IL-10 showed no significant difference.

Figure 2.

Serum cytokine levels in lymphatic filariasis (LF)-negative and LF-positive CAD subjects. Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (A), interleukin (IL)-6 (B), IL-1β (C), and IL-10 (D) are shown. Each dot represents an individual patient, with the geometric mean represented by the horizontal bars. P values were calculated by Mann-Whitney U test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

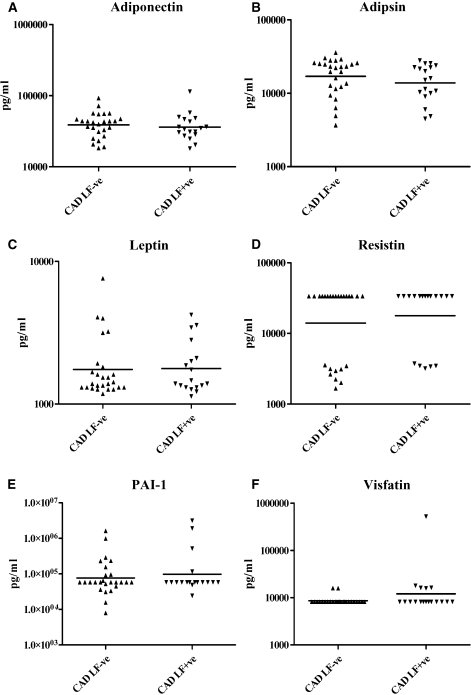

Serum adipocytokine analysis in subjects with CAD and/or LF.

We next quantified serum adipocytokine levels in subjects with CAD and/or LF (Figure 3). No significant difference was seen in the serum levels of adiponectin, adipsin, leptin, resistin, PAI-1, and visfatin between the groups. The serum adipocytokine profile was unaffected by the LF status.

Figure 3.

Serum adipocytokine levels in lymphatic filariasis (LF)-negative and LF-positive CAD subjects. Serum levels of Adiponectin (A), Adipsin (B), Leptin (C), Resistin (D), PAI-1 (E), and Visfatin (F) are shown. Each dot represents an individual patient, with the geometric mean represented by the horizontal bars. P values were calculated by Mann-Whitney U test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Discussion

The hypothesis that parasitic helminths may protect against the development of allergic and autoimmune processes has spurred an interest in examining the protective effects of helminths and their immunomodulatory products in these processes (hygiene hypothesis).15 In addition, clinical trials examining the effect of helminth products on disease severity in autoimmune diseases16 have shown promising results. The safety of these products for use as therapeutic agents has also been documented.17 However, little is known about the association of helminth infections with metabolic diseases of inflammatory origin. Previously, we have shown reduced prevalence of LF among T2DM subjects and have also provided evidence for the possible involvement of filarial-mediated immune modulation in possibly conferring protection against T2DM (extended hygiene hypothesis).9 Recently, our findings were confirmed in a murine model of high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance, infected with the intestinal helminth, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis.18 On the basis of these findings, we looked at the prevalence of LF among our CAD subjects. We found no significant difference in the prevalence of LF among the CAD− and CAD+ subjects. There was also no significant difference in the serum antigen levels (which is an indicator of active infection) and anti-LF antibody titers (an indicator of exposure). To avoid the confounding effect of diabetes, subjects who had diabetes (both type-1 and type-2) were excluded from this study. In addition, differences in socioeconomic status, another potential confounding factor, was also shown to be noncontributory in the context of the present study (see Supplementary Table 1), because no differences were seen in socioeconomic status between the CAD− and CAD+ groups.

During the past two decades, work conducted at many laboratories has defined CAD as a chronic inflammatory disease.19 Studies in mice and humans have shown that inflammation promotes all phases of atherosclerosis, including initiation, progression, and disruption of the atheroma. Indeed, increased levels of serum hsCRP, an acute phase protein, is the single definitive risk factor for cardiovascular events.20 Even though the inflammatory origin of CAD has now been well established the link between infections and inflammation seen in CAD is poorly understood. Only recently have studies examining the interaction of metabolic and infectious diseases gained importance.21 The earliest of these reports showed some association between severe respiratory tract infections and CAD.22 Apart from respiratory tract infections, oral infections,23 gut infections (especially Helicobacter pylori infection),24 and urinary tract infections have also been associated with CAD. In general, evidence suggests that the infections that induce systemic inflammation promote CAD. In contrast to most viral and bacterial diseases, which are known to promote inflammation, helminth infections are known to downregulate inflammation by immunomodulation15; until now, the effect of filarial infections on CAD has not been studied, even in animal models. In this study, the prevalence of LF was found to be comparable between CAD− and CAD+ groups. In terms of humoral responses against filariasis, both subjects with active filarial infection and those who are exposed but resistant to infection mount vigorous humoral response to parasite antigen, most specifically, IgG antibody.25 Thus, BmA-specific IgG can be considered to be a good surrogate marker for exposure. The comparable antigen and IgG levels between the groups indicate similar rates of exposure and infection between these subjects, because they come from the endemic area and are of comparable socio-economic status (data not shown). Furthermore, LF infection had no effect on CAD-specific markers like IMT and hsCRP.

In our previous study, LF+ diabetic subjects had significantly lower levels of serum pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6), compared with LF− diabetic subjects. In contrast to diabetes, in CAD, the presence of LF was associated with a significant increase in serum TNF-α and IL-6 but not IL-1β and IL-10 levels. Therefore, filarial infections appear to augment inflammation in CAD subjects. It is important to note that inflammation seen in metabolic diseases like obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance, and CAD are not necessarily mediated by the same group of cytokines and scant attention has been paid toward deciphering disease-specific inflammation among metabolic disorders. Therefore, LF-mediated immunomodulation could possibly have different effects depending upon the nature of the underlying inflammation.26 Finally, adipocytokines play an important role in glucose, lipid, and lipoprotein metabolism, and in coagulation and arterial inflammation.27 Several studies have evaluated the association of adipokines with CAD and have provided mixed results.28 In general, low levels of serum adiponectin have been associated with diabetes and CAD but this was dependent upon the obesity status.29 In this study the adipocytokine levels were not altered by LF infection among CAD+ subjects. However, our study clearly indicates that helminth-mediated immunomodulation need not be universal but might actually be disease/inflammation specific.

Limitation.

This study suffers from the limitation of being a cross-sectional study and therefore not providing a direct cause and effect mechanism.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the MDRF epidemiology team members for conducting the CURES field studies. This is the 121th paper from CURES.

Note: Supplemental table is available at www.ajtmh.org/content/86/5/828/suppl/DC1.

Footnotes

Financial support: This work received partial support from the Intramural Research Program of the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, through the NIAID/TRC ICER program and KB Chandrasekhar Research Foundation, India.

Authors' addresses: Vivekanandhan Aravindhan, Anna University-KB Chandrasekhar Research Centre, MIT Campus of Anna University, Chrompet, Chennai, India, E-mail: cvaravindhan@gmail.com. Vishwanathan Mohan, Jayagopi Surendar, Mardana Muralidhara Rao, and Mohan Deepa, Madras Diabetes Research Foundation, Chennai, India, E-mails: drmohans@vsnl.net, surendarj85@gmail.com, raoinfoster@gmail.com, and deepa.mohan1@gmail.com. Rajamanickam Anuradha, Tuberculosis Research Center-National Institutes of Health-International Center for Excellence in Research, Chetpet, Chennai, India, E-mail: anuvenil@gmail.com. Subash Babu, Tuberculosis Research Center, Chennai, India; National Institutes of Health-International Center for Excellence in Research, Chetpet, Chennai, India; and SAIC Frederick, Inc., NCI Frederick, Frederick, MD, E-mail: sbabu@mail.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta R, Misra A, Pais P, Rastogi P, Gupta VP. Correlation of regional cardiovascular disease mortality in India with lifestyle and nutritional factors. Int J Cardiol. 2006;108:291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choudhury RP, Fisher EA. Molecular imaging in atherosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:983–991. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.165498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nieto FJ. Viruses and atherosclerosis: a critical review of the epidemiologic evidence. Am Heart J. 1999;138:S453–S460. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah PK. Link between infection and atherosclerosis: who are the culprits: viruses, bacteria, both, or neither? Circulation. 2001;103:5–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Riet E, Hartgers FC, Yazdanbakhsh M. Chronic helminth infections induce immunomodulation: consequences and mechanisms. Immunobiology. 2007;212:475–490. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Self LS. A different perspective on global mapping of lymphatic filariasis. Parasitol Today. 1998;14:333. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(98)01277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aravindhan V, Mohan V, Surendar J, Rao MM, Ranjani H, Kumaraswami V, Nutman TB, Babu S. Decreased prevalence of lymphatic filariasis among subjects with type-1 diabetes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:1336–1339. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aravindhan V, Mohan V, Surendar J, Muralidhara Rao M, Pavankumar N, Deepa M, Rajagopalan R, Kumaraswami V, Nutman TB, Babu S. Decreased prevalence of lymphatic filariasis among diabetic subjects associated with a diminished pro-inflammatory cytokine response (CURES 83) PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deepa M, Pradeepa R, Rema M, Mohan A, Deepa R, Shanthirani S, Mohan V. The Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES)–study design and methodology (urban component) (CURES-I) J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:863–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohan V, Ravikumar R, Shanthi Rani S, Deepa R. Intimal medial thickness of the carotid artery in South Indian diabetic and non-diabetic subjects: the Chennai Urban Population Study (CUPS) Diabetologia. 2000;43:494–499. doi: 10.1007/s001250051334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gokulakrishnan K, Deepa R, Mohan V. Association of high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) with carotid intimal medial thickness in subjects with different grades of glucose intolerance–the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES-31) Clin Biochem. 2008;41:480–485. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pignoli P, Longo T. Ultrasound evaluation of atherosclerosis. Methodological problems and technological developments. Eur Surg Res. 1986;18:238–253. doi: 10.1159/000128532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lonn EM, Yusuf S, Doris CI, Sabine MJ, Dzavik V, Hutchison K, Riley WA, Tucker J, Pogue J, Taylor W. Study design and baseline characteristics of the study to evaluate carotid ultrasound changes in patients treated with ramipril and vitamin E: SECURE. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:914–919. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00467-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooke A. Review series on helminths, immune modulation and the hygiene hypothesis: how might infection modulate the onset of type 1 diabetes? Immunology. 2009;126:12–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinstock JV, Elliott DE. Helminths and the IBD hygiene hypothesis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:128–133. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harnett MM, Melendez AJ, Harnett W. The therapeutic potential of the filarial nematode-derived immunodulator, ES-62 in inflammatory disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;159:256–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu D, Molofsky AB, Liang HE, Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Jouihan HA, Bando JK, Chawla A, Locksley RM. Eosinophils sustain adipose alternatively activated macrophages associated with glucose homeostasis. Science. 2011;332:243–247. doi: 10.1126/science.1201475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs M, van Greevenbroek MM, van der Kallen CJ, Ferreira I, Blaak EE, Feskens EJ, Jansen EH, Schalkwijk CG, Stehouwer CD. Low-grade inflammation can partly explain the association between the metabolic syndrome and either coronary artery disease or severity of peripheral arterial disease: the CODAM study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009;39:437–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogh AL, Joensen J, Lindholt JS, Jacobsen MR, Ostergaard L. C-reactive protein predicts future arterial and cardiovascular events in patients with symptomatic peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2008;42:341–347. doi: 10.1177/1538574408316138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell DS. Inflammation, insulin resistance, infection, diabetes, and atherosclerosis. Endocr Pract. 2000;6:272–276. doi: 10.4158/EP.6.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell LA, Yaraei K, Van Lenten B, Chait A, Blessing E, Kuo CC, Nosaka T, Ricks J, Rosenfeld ME. The acute phase reactant response to respiratory infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae: implications for the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Microbes Infect. 2010;12:598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kebschull M, Demmer RT, Papapanou PN. “Gum bug, leave my heart alone!”–epidemiologic and mechanistic evidence linking periodontal infections and atherosclerosis. J Dent Res. 2010;89:879–902. doi: 10.1177/0022034510375281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kusters JG, Kuipers EJ. Helicobacter and atherosclerosis. Am Heart J. 1999;138:S523–S527. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lal RB, Ottesen EA. Enhanced diagnostic specificity in human filariasis by IgG4 antibody assessment. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:1034–1037. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.5.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter MM, Wang A, McKay DM. Helminth infection enhances disease in a murine TH2 model of colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1320–1330. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuzawa Y, Shimomura I, Kihara S, Funahashi T. Importance of adipocytokines in obesity-related diseases. Horm Res. 2003;60((Suppl 3)):56–59. doi: 10.1159/000074502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matarese G, Mantzoros C, La Cava A. Leptin and adipocytokines: bridging the gap between immunity and atherosclerosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:3676–3680. doi: 10.2174/138161207783018635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasan-Ali H, Abd El-Mottaleb NA, Hamed HB, Abd-Elsayed A. Serum adiponectin and leptin as predictors of the presence and degree of coronary atherosclerosis. Coron Artery Dis. 2011;22:264–269. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e3283452431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.