Abstract

Eosinophilic otitis media (EOM) is a relatively rare, intractable, middle ear disease with extremely viscous mucoid effusion containing eosinophils. EOM is associated with adult bronchial asthma and nasal allergies. Conventional treatments for otitis media with effusion (OME) or for chronic otitis media (COM), like tympanoplasty or mastoidectomy, when performed for the treatment of EOM, can induce severe complications such as deafness. Therefore, it should be differentiated from the usual type of OME or COM. To our knowledge, the clinical and imaging findings of EOM of temporal bone are not well-known to radiologists. We report here the CT and MRI findings of two EOM cases and review the clinical and histopathologic findings of this recently described disease entity.

Keywords: Eosinophilic otitis media, Imaging findings of EOM

INTRODUCTION

The basic pathophysiologic mechanism of otitis media with effusion (OME) or chronic otitis media (COM) is impaired ventilation of the middle ear cavity and mastoid air cells usually caused by Eustachian tube dysfunction secondary to swelling of the nasal mucosa or mucous stasis around the pharyngeal orifice of the Eustachian tube (1). Conventional treatments for OME or COM include myringotomy, insertion of a tympanostomy tube, administration of antibiotics or ear surgery in advanced cases (2).

Eosinophilic otitis media is characterized by extreme viscous mucoid effusion containing eosinophils and is associated with a history of adult bronchial asthma and nasal allergies (3). EOM is typically intractable to conventional treatments for OME or COM, and there is no effective treatment except for systemic administration of steroids in cases of EOM. However, most patients with EOM are treated for COM for a prolonged period of time by therapies such as tympanoplasty or mastoidectomy for EOM, usually induce deterioration of hearing symptoms (2). Therefore, accurate diagnosis and treatment are necessary in order to avoid inadequate treatment and severe complications such as deafness.

To our knowledge, the imaging findings of EOM of the temporal bone have rarely been reported in the literature (4). We present imaging findings of pathologically confirmed EOM in two patients and review this recently described disease entity.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

A 37-year-old woman visited our hospital with a bilateral hearing disturbance which had been aggravated for six years. She had a five-year history of otorrhea in both ears and had been treated conservatively with topical and oral antibiotics for the presumptive diagnosis of bilateral COM with cholesteatoma. She had a past medical history of longstanding allergic rhinitis and bronchial asthma and had been on medication for this for the past 10 years.

An otoscopic examination revealed turbidity of the bilateral tympanic membranes with middle ear effusion. Pure-tone audiometry (PTA) and the speech reception threshold test (SRT) revealed bilateral profound conductive hearing loss: 8 dB for the right ear and 5 dB for the left ear on PTA; 50 dB for the right ear and 48 dB for the left ear on SRT.

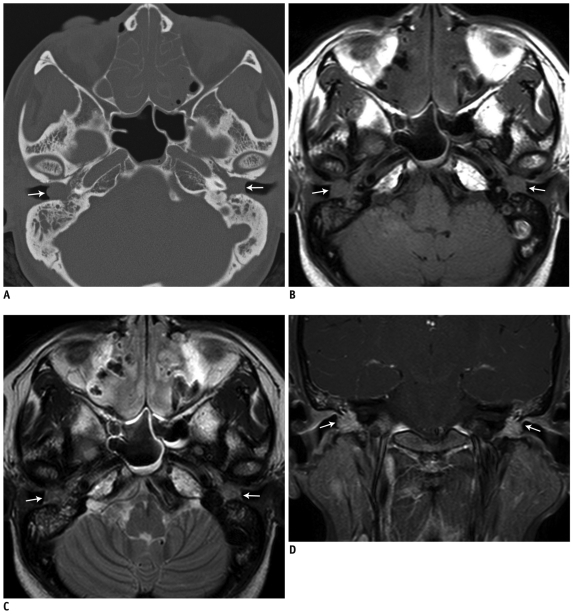

Temporal bone CT (TBCT) performed at a private clinic two weeks ago revealed complete soft-tissue filling of the bilateral middle ear cavity without bony erosion and the sclerotic mastoid, resulting in bulging of the tympanic membranes (Fig. 1). TBCT also demonstrated mucosal thickening of the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses, caused by inflammation. Temporal bone MRI for further evaluation showed T1 low and T2 intermediate signal, as well as enhancing lesion filling in the bilateral middle ear cavity. These MR findings are suggesting rich granulation tissue in the middle ear cavity rather than acquired cholesteatoma. The possibility of tumors such as adenoma or adenoid cystic carcinoma was very low from its bilaterality and from the findings of TBCT.

Fig. 1.

37-year-old woman with progressive, bilateral hearing disturbance.

(A) TBCT shows complete soft-tissue filling in bilateral middle ear cavities (arrow) and sclerotic mastoid. No bony erosion, except for minimal marginal erosion of ossicular chain is seen. Ethmoid sinuses are completely obliterated by thickened mucosa, which is also seen in sphenoid sinuses. (B-D) TBMR shows T1 low- (B) and T2 intermediate- (C) signal-intensity soft-tissue lesions filling both middle ear cavities (arrow) with mild heterogeneous contrast enhancement (D) suggesting granulation tissue. TBCT = temporal bone CT

The patient underwent endoscopic sinus surgery and intact canal wall mastoidectomy on the right temporal bone within an interval of one month. On the surgical field, granulation tissue was found to be extruded to the external auditory canal from the middle ear cavity through the perforated tympanic membrane. The mastoid antrum and the air-cells were filled with purulent exudate and granulation tissue which had eroded the bony cortex of the mastoid air-cells. Histopathologic examination only revealed a large amount of granulation tissue with chronic active inflammatory cells. There was no histologic evidence of vasculitis or granulomatous inflammation. No micro-organisms were identified by the PAS, GMS, gram or Ziehl-Neelsen staining.

Approximately four weeks following surgery, the patient visited the outpatient clinic again because of recurrent ear fullness. Otoscopic examination and follow-up TBCT revealed a recurrent, bulging mass from the right middle ear cavity and the mastoid protruding into the external auditory canal, which had gradually increased during the six-month follow-up. She underwent revision tympanoplasty and mastoidectomy on the right ear, which revealed chronic inflammatory infiltration with numerous eosinophils as well as Chartcot-Layden crystals within the inflammatory exudate. Based on these findings, this case was finally diagnosed as EOM. The patient was administered a high-dose steroid therapy to control the inflammation. During the five-month follow-up, there was neither recurrence of her symptoms nor bulging granulation tissue seen on the otoscopic examination.

Case 2

A 33-year-old man was referred to our hospital for treatment of intractable otorrhea in his left ear. A bilateral hearing disturbance had been aggravated for two years during medical treatment of his longstanding, bilateral, chronic, recurrent sinusitis and bronchial asthma. Approximately six months prior, he had undergone a right simple mastoidectomy at a private clinic for the diagnosis of the bilateral chronic otomastoiditis.

An otoscopic examination revealed a polypoid mass with purulent discharge in the left ear. In the right ear, there was no specific finding except for crust from the previous operation. PTA and SRT revealed hearing difficulty in the bilateral ears. His hearing level was 7 dB for the right ear and 8 dB for the left ear, as seen on PTA. SRT showed 16 dB in the right ear and 24 dB in the left ear.

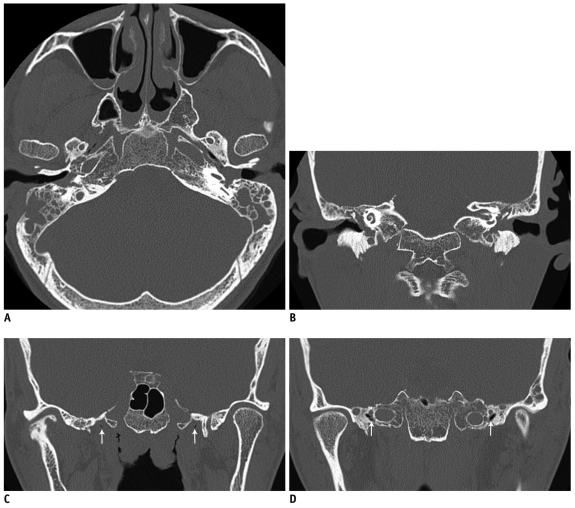

Temporal bone CT demonstrated that both the middle ears and the mastoid air cells were filled with soft tissue without erosion, thus suggesting bilateral otomastoiditis. The axial images also demonstrated bilateral maxillary sinusitis (Fig. 2). From the clinical and imaging findings, the preoperative diagnosis was an inflammatory polyp associated with chronic otomastoiditis.

Fig. 2.

33-year-old man with persistent otorrhea.

A, B. Axial and coronal TBCT images demonstrate soft-tissue lesions bulging from bilateral middle-ear cavities and filling mastoid air cells. There is no evidence of bony erosion except for bony defect at right mastoid from previous surgery. Mucosal thickening of bilateral maxillary sinus is also shown. C, D. Bilateral Eustachian tubes are clearly traced on serial coronal TBCT images (arrows). TBCT = temporal bone CT

For the polyp of the left ear, endoscopic polypectomy was performed. Histopathologic findings showed granulation tissue with moderate lymphoplastic infiltration and with eosinophils. Based on these findings, this patient was also finally diagnosed with EOM. The patient also received a high-dose steroid therapy to control the inflammation, which resulted in a decrease in discharge in both ears. Two months later, there was no further ear discharge.

DISCUSSION

EOM is a relatively rare, intractable disease characterized by the presence of a highly viscous yellow effusion with extensive accumulation of eosinophils in the middle ear (5). The mechanism underlying ear damage caused by eosinophilic inflammation is still unclear. On physical examination, most EOM patients show a patulous Eustachian tube rather than tubal stenosis, which is different from OME or COM. Iino et al. suggested that in patients with T helper type 2-dominant predisposition, such as bronchial asthma, an antigenic material may easily invade via a patulous Eustachian tube and stimulate inflammatory cells, thus resulting in the accumulation of eosinophils and further inducing fibroblasts or endothelial cells to produce eosinophil chemoattractants (2). The cytotoxic proteins and active oxygen species generated by eosinophils may damage the epithelial layer, including the round window membrane, and lipid mediators released from eosinophils render the membrane permeable. These events allow inflammatory substances such as bacterial toxins and inflammatory cytokines to enter into the middle and inner ear, thus resulting in ear damage. Therefore the systemic or topical glucocorticoid is believed to be the most effective treatment for EOM (2).

Nagamine et al. (5) revealed that the pharyngeal orifice of the Eustachian tubes was not markedly edematous and that the Eustachian tube dysfunction was not always obstructive but sometimes patulous in EOM patients. A middle-ear condition for EOM could be an eosinophilic inflammation of the middle ear, itself, rather than that caused by secondary allergic inflammation of the nose. Based on these observations, Iino et al. (6) proposed the diagnostic criteria of EOM in 2011; a patient who shows OME or COM with eosinophil-dominant effusion (major criterion) and with two or more among the highest four items (minor criteria): highly viscous middle ear effusion; resistance to conventional treatment for OME association with bronchial asthma; and association with nasal polyposis.

In our two cases, the symptoms, including persistent otorrhea and progressive hearing disturbance, were initially misdiagnosed as COM. However, the histopathological findings of these lesions showed chronic inflammatory infiltration with numerous eosinophils. They also had bronchial asthma and chronic recurrent sinusitis. From a retrospective review of TBCT in the present cases, we could see an unusual large polypoid mass bulging from the inflamed middle-ear cavities, similar to that seen in the sinonasal cavities. Furthermore, in the second case, we could see that the lumina of the bilateral Eustachian tubes were clearly traced on serial images, which are not commonly observed findings in usual OME or COM patients with paranasal sinus inflammation.

The prospective radiologic diagnosis of the eosinophilic otitis media is nonetheless difficult, probably because of the rarity of this lesion and the few cases studied with CT or MR imaging described in the literature, which may lead to an erroneous preoperative diagnosis of EOM. On a CT scan, image findings of EOM might be similar to COM, with heterogeneous soft tissue within the middle ear and mastoid, with or without minimal erosion of the ossicles. However, there are some findings providing clues for differentiating EOM from COM on CT and MR images. EOM shows higher incidences of bilaterality and chronic rhinosinusitis. Also, it can be accompanied by the patulous Eustachian tubes distinctively. We consider these collective findings as helpful imaging criteria to suggest a diagnosis of EOM on TBCT, but these findings should be verified in a larger study. Although cholesteatoma, keratosis obturans, or medial canal fibrosis involving the external auditory canal could be considered as part of the differential diagnoses, they can be differentiated from EOM by the presence of bony erosion or predominant involvement of external auditory canal.

Iwasaki et al. (4) reported an EOM patient who had noted sudden bilateral deafness and vertigo. In that case, TBCT performed after the systemic steroid demonstrated ossification of the cochlea at the symptomatic side. They speculated that the accumulation of activated eosinophils induced by mastoid surgery may increase the susceptibility of the infiltration of protein associated with tissue damage to the round window membrane. Therefore, they suggested that tympanoplasty and mastoidectomy should be contraindicated for eosinopilic otitis media.

In the EOM patient who suffered from severe chronic recurrent otitis media with eardrum damage, even tympanoplasty can make the disease worse. Although the exact mechanism has not yet been elucidated, Tomioka et al. reported a patient who finally became deaf in both ears several years after ear surgery. A multi-institutional study showed a significantly higher ratio of deafness among patients s compared to those without tympanoplasty (17% vs. 4%, p < 0.05) (4). Therefore, adequate diagnosis and treatment are necessary in order to avoid severe complications such as deafness.

Conclusion

Despite its rarity, EOM should be discriminated from the usual OME or COM associated with impaired ventilation of the middle ear. Smooth, soft-tissue bulging from the inflamed middle ear cavity, bilateral paranasal sinusitis, and clearly visible tubal Eustachian tubal lumina may be the diagnostic hallmark seen on TBCT in EOM.

References

- 1.Sipilä P, Karma P. Inflammatory cells in mucoid effusion of secretory otitis media. Acta Otolaryngol. 1982;94:467–472. doi: 10.3109/00016488209128936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iino Y, Usubuchi H, Kodama K, Kanazawa H, Takizawa K, Kanazawa T, et al. Eosinophilic inflammation in the middle ear induces deterioration of bone-conduction hearing level in patients with eosinophilic otitis media. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31:100–104. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181bc3781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iino Y, Kakizaki K, Saruya S, Katano H, Komiya T, Kodera K, et al. Eustachian tube function in patients with eosinophilic otitis media associated with bronchial asthma evaluated by sonotubometry. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:1109–1114. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.10.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwasaki S, Nagura M, Mizuta K. Cochlear implantation in a patient with eosinophilic otitis media. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:365–369. doi: 10.1007/s00405-005-1006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagamine H, Iino Y, Kojima C, Miyazawa T, Iida T. Clinical characteristics of so called eosinophilic otitis media. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2002;29:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(01)00124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iino Y, Tomioka-Matsutani S, Matsubara A, Nakagawa T, Nonaka M. Diagnostic criteria of eosinophilic otitis media, a newly recognized middle ear disease. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2011;38:456–461. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]