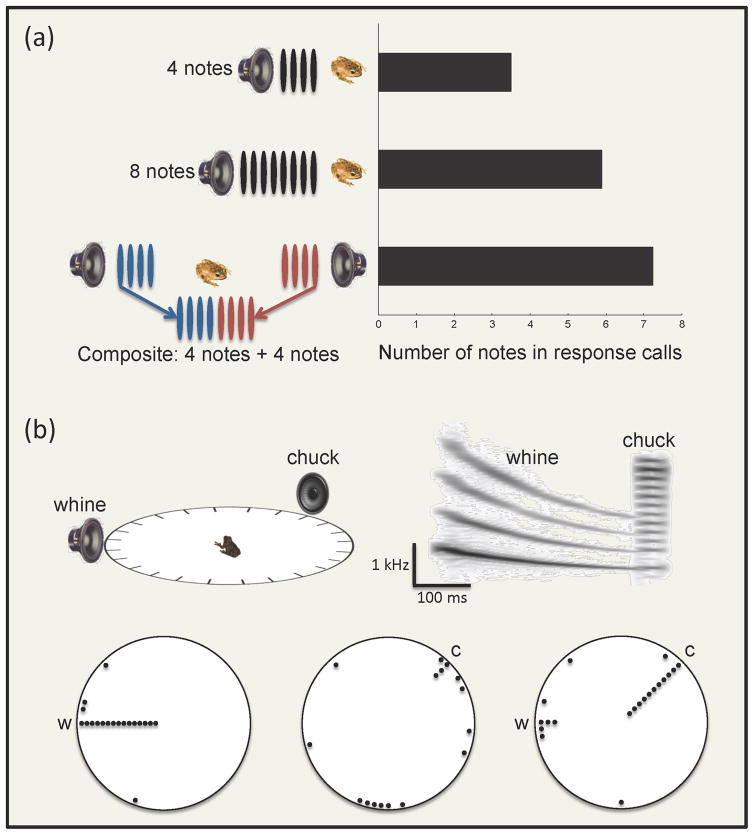

Figure 3.

Sequential integration in frogs based on common spatial origin. Frog calls typically comprise multiple sound elements (e.g., notes or pulses) separated in time. For many species, recognizing conspecific calls or selecting high-quality mates requires that receivers perceptually bind temporally separated sound elements into coherent “auditory objects.” Several studies directly or indirectly investigating the role of common spatial origin as an auditory grouping cue indicate that frogs may be fairly permissive of spatial incoherence in recognizing or preferring certain calls. (a) In a field playback experiment, males of the Australian quacking frog (Crinia georgiana) were shown to closely match the number of notes in stimulus calls simulating nearby neighbors [40]. However, males gave calls with similar numbers of response notes to 8-note stimulus calls coming from one direction and composite 8-note calls in which the first and second four notes of the call came from speakers separated by 180° [40]. (b) Laboratory studies of phonotaxis in túngara frogs (Engystomops pustulosus) have also found that females can be permissive of wide angular separations between the preferred “whine” and “chuck” components of complex calls [45]. Whines (w) presented alone elicited robust phonotaxis (indicated here by orientation angles at which females exited the circular test arena relative to the position of the speaker broadcasting the stimulus [45]. Chucks (c) alone failed to elicit phonotaxis; however, whine-chuck sequences elicited phonotaxis directed toward the chuck even when it was separated from the whine by up to 135° [45]. Together, these and other studies [41–44] indicate that frogs can be permissive of spatial incoherence and will perceptually group sounds together even though they originate from different locations.