Abstract

In utero, pulmonary blood flow is closely circumscribed and oxygenation and ventilation occur via the placental circulation. Within the first few breaths of air-breathing life, the perinatal pulmonary circulation undergoes a dramatic transition as pulmonary blood flow increases 10-fold and the pulmonary arterial blood pressure decreases by 50% within 24 hours of birth. With the loss of the placental circulation, the increase in pulmonary flow enables oxygen to enter the bloodstream. The physiologic mechanisms that account for the remarkable transition of the pulmonary circulation include establishment of an air-liquid interface, rhythmic distention of the lung, an increase in shear stress and elaboration of nitric oxide from the pulmonary endothelium. If the perinatal pulmonary circulation does not dilate, blood is shunted away from the lungs at the level of the patent foramen ovale and the ductus arteriosus leading to the profound and unremitting hypoxemia that characterizes persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN), a syndrome without either optimally effective preventative or treatment strategies. Despite significant advances in treatment, PPHN remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in neonatal centers across the globe. While there is information surrounding factors that might increase the risk of PPHN, knowledge remains incomplete. Cesarean section delivery, high maternal body mass index, maternal use of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and maternal diabetes mellitus are among the factors associated with an increased risk for PPHN. Recent data suggest that maternal use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors might represent another important risk factor for PPHN.

Keywords: cesarean section, persistant pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, pulmonary circulation, serotonin reuptake inhibitors

INTRODUCTION

Perinatal pulmonary vasodilation

In utero, oxygen tension is low and pulmonary vascular resistance is greater than systemic vascular resistance.[1] At birth, the pulmonary circulation undergoes an unprecedented and unparalleled transition, as pulmonary blood flow increases 8- to 10-fold and arterial pressure decreases by 50% within 24 hours concomitant with an increase in oxygen tension, establishment of an air-liquid interface and rhythmic distention of the lung.[2–4]

In 1953, Dawes and coworkers performed a seminal study of the transitional pulmonary circulation. The study demonstrated that ventilation and establishment of an air-liquid interface caused an immediate increase in pulmonary blood flow and a decrease in pulmonary arterial blood pressure.[4] Evidence for an integral role for oxygen in the postnatal adaptation of the pulmonary circulation came first with the finding that while ventilation with nitrogen caused pulmonary vasodilation, ventilation with O2caused even greater pulmonary vasodilation.[5]

The demonstration that fetal blood flow increased more than 3-fold when pregnant ewes were placed in a hyperbaric chamber provided clear evidence that an increase in fetal oxygen tension alone, absent of any other stimulus, could cause fetal pulmonary vasodilation.[6] The discovery that during the transition of the pulmonary circulation prostaglandin production from pulmonary endothelium increased[7] suggested that vasoactive mediators produced by the endothelium might modulate perinatal pulmonary vascular tone. While blockade of prostaglandin production prevented neither perinatal pulmonary vasodilation[8] nor oxygen-induced fetal pulmonary vasodilation,[9] the observation that pharmacologic blockade of endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF), later identified as nitric oxide (NO),[10–12] prevented the postnatal adaptation of the pulmonary circulation[13] demonstrated the critical importance of the pulmonary endothelium in the postnatal adaptation of the pulmonary circulation.

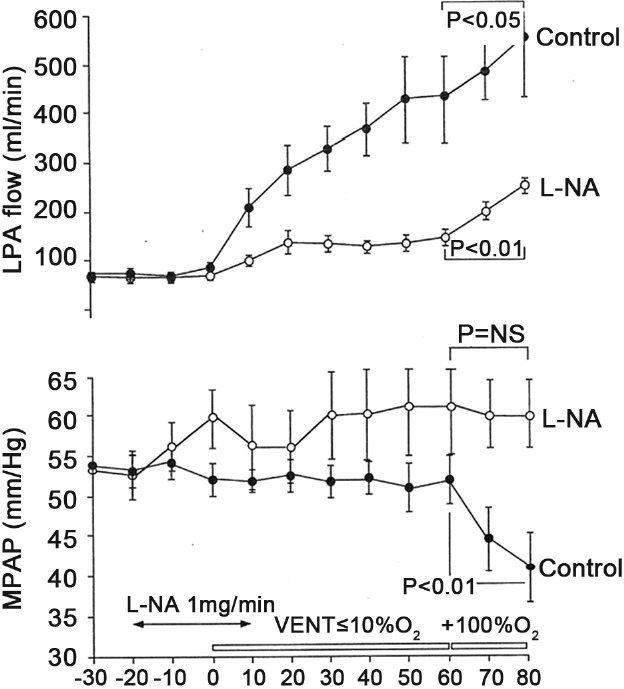

Pharmacologic inhibition of NO production also attenuated the decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance with both ventilation alone and ventilation with 100% O2, providing direct evidence that NO production played a key role in O2-induced fetal pulmonary vasodilation (Fig. 1).[14] Two separate studies found that O2-induced pulmonary vasodilation was either attenuated or prevented by blockade of NO in the chronically instrumented fetal lamb.[15,16] These findings, together with the observation that O2tension is capable of modulating NO production in fetal PA endothelial cells,[17] implied that the increase in O2tension that occurs at birth may contribute to sustained and progressive pulmonary vasodilation by providing a stimulus for augmented NO production by the pulmonary endothelium.

Figure 1.

Hemodynamic effects of pharmacologic inhibition of nitric oxide (L-NA) on left pulmonary arterial blood flow (LPA flow; top panel) and mean pulmonary arterial pressure (MPAP; bottom panel) during sequential ventilation with low and high concentrations of oxygen. In comparison with control animals (closed circles; n=6 animals), inhibition of nitric oxide (open circles; n=7 animals) markedly attenuated rise in LPA flow during ventilation with low and high fraction of inspired oxygen concentration as well as the decline in mean pulmonary artery pressure during ventilation with high fractional concentration of inspired oxygen.[14]

Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn

In some newborn infants, pulmonary vascular resistance remains elevated after birth, resulting in shunting of blood away from the lungs and severe central hypoxemia.[18] Infants with the condition, termed persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN), often respond only incompletely to administration of high concentrations of supplemental oxygen or inhaled nitric oxide.[19]

Although persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) may be the result of several divergent neonatal disorders, abnormal pulmonary vasoreactivity, marked pulmonary hypertension, incomplete response to vasodilator stimuli,[20] increase in circulating levels of endothelin and histologic changes in the pulmonary vasculature (in infants dying as a result of PPHN) are all consistent hallmarks of the syndrome.[18] Adverse intrauterine stimuli such as chronic hypoxia[21] or hypertension[22] can lead to pathophysiology that closely resembles PPHN. In fetal sheep, chronic intrauterine pulmonary hypertension leads to vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, perivascular adventitial thickening[23–26] and a progressive decrease in the pulmonary vasodilator response to oxygen and acetylcholine.[27] Data derived from fetal lambs with chronic intrauterine pulmonary hypertension due to ligation of the ductus arteriosus indicate that decreases in endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) gene and protein expression[28,29] may limit perinatal NO production, thereby contributing to the pathophysiology of PPHN.[28–30] In addition, sensitivity to NO may be decreased by chronic intrauterine hypertension.[31] Evidence shows that intrauterine pulmonary hypertension causes pulmonary vascular smooth muscle hypertrophy[24] and decreases myosin light chain phosphatase levels.[25]

Endothelin, a 21 amino acid polypeptide elaborated by the endothelium, has been shown to be a powerful vasoconstrictor and mitogen. Identified in 1987, endothelin has complex actions during cardiopulmonary development.[32,33] Endothelin is essential for normal cardiovascular development, as mice lacking the endothelin gene manifest lethal vascular abnormalities, including a hypoplastic aortic arch.[34,35] Circulating levels of endothelin levels are increased in human infants with PPHN,[32,33] concomitant with a decrease in cGMP concentration.[36] Endothelin receptor blockade in the ovine fetus results in substantial vasodilation,[37] suggesting that endothelin plays a role in the closely circumscribed pulmonary blood flow that characterizes fetal life. Despite the advent of selective endothelin receptor antagonists for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension, none have been applied to PPHN. Enhanced understanding of the effects of endothelin on PA SMC from both normal and hypertensive fetuses will increase the likelihood that endothelin-based therapies might be applied to neonatal pulmonary hypertension.

Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn risk factors

While an incomplete response to pulmonary vasodilator stimuli characterizes PPHN,[38] the factors that definitively increase the risk of PPHN remain uncertain. Perinatal risk factors for PPHN include pulmonary parenchymal disease, such as meconium aspiration or pneumonia, which clearly increases the likelihood that infants will develop PPHN. Infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) possess physiology that is consistent with PPHN as pulmonary vascular resistance remains elevated and blood is shunted away from the lungs.

Lung structural abnormalities

Children with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) are at risk for PPHN. The incidence of CDH is 1 in 2,000-3,000 live births.[39] Despite meaningful advances in neonatal intensive care, the mortality rate in infants with CDH is approximately 60%. Refractory pulmonary hypertension is the primary cause of mortality in infants with CDH. In 1951, Reid et al. demonstrated that airway number, and therefore the alveolar, acinar and arterial number is reduced in both lungs of patients with CDH.[40] The decrease is most pronounced in the lung that is ipsilateral to the defect.[40] In infants with CDH, endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression is decreased[41] and endothelin expression is increased.[42] The cause for pulmonary vascular remodeling in CDH remains unknown.

Mode of delivery

Increasing evidence suggests that mode of delivery is a significant determinant of the relative risk of PPHN. In a well-considered, case-control trial performed in the United States Army population, infants delivered via Cesarean section possessed an almost 5-fold increased risk of developing PPHN compared to a demographically well-matched control population.[43] While the study included almost 12,000 infants, only 20 developed PPHN. In this study, choramnionitis also conferred a significantly increased risk, more than 3-fold, of PPHN. The notion that Cesarean section delivery increases risk of PPHN is supported by data from an earlier study wherein mode of delivery, maternal race (Black, Asian) and high maternal body mass index each increased the likelihood of PPHN.[44]

Antenatal drug exposure

Among the most significant risk factors for PPHN is maternal medication usage. Compared to control infants, in utero exposure to aspirin increases the risk of PPHN by 4.9-fold while NSAID exposure increases the likelihood of PPHN by more than 6-fold.[45] The mechanistic link between these medications and the risk of PPHN may relate to the importance of prostaglandins in maintaining patency of the ductus arteriosus. Aspirin and NSAID block prostaglandin and thromboxane synthesis and may cause premature ductus arteriosus closure, and elevate both blood pressure and shear stress in the pulmonary circulation.[22] Surgical ligation of the ductus arteriosus in sheep was initially described as a model for in utero pulmonary hypertension in 1972.[46] Further insight into the implications of ductal ligation derives from a report by Abman et al. demonstrating that libation of the ductus arteriosus resulted in increased pulmonary vascular reactivity, increased muscularization of the pulmonary circulation and physiology entirely consistent with PPHN.[47]

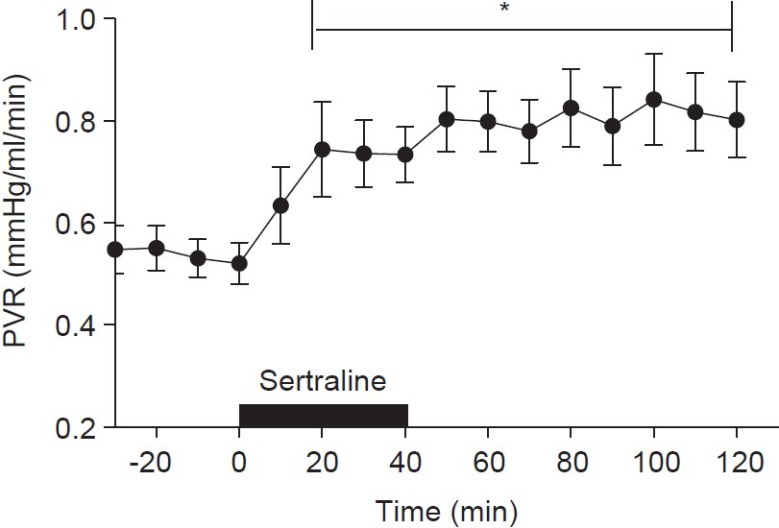

Recent epidemiologic studies have demonstrated an association between maternal use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and PPHN, with SSRI use within the second half of pregnancy conferring a 6-fold increase in the risk of developing of PPHN.[48] Interpretation of these data is confounded by the prevalence of maternal depression among women in childbearing years. The study had a case-control design and reported that among the 20 infants with PPHN, 14 had been exposed to SSRI in utero after week 20 of gestation.[48] SSRI readily cross the placenta, as reflected by fetal cord blood levels corresponding to 30%-70% of maternal levels.[22,50] The mechanism whereby SSRI affect the fetal and neonatal pulmonary circulation remains unknown. However, data in adult mice indicate that overexpression of the 5-HT transporter gene potentiates hypoxic pulmonary hypertension by increasing vascular remodeling.[49] SSRI may increase fetal serotonin (5-HT) levels. Serotonin is a potent vasoconstrictor and stimulates smooth muscle cell growth and proliferation.[50–53] Recent studies have demonstrated that SSRI infusion into the fetal pulmonary circulation results in potent and sustained elevation of pulmonary vascular resistance (Fig. 2).[54] Moreover, maternal treatment with the SSRI fluoxetine leads to pulmonary hypertension in rat pups, as evidenced by pulmonary vascular remodeling, right ventricular hypertrophy, decreased oxygenation, and higher perinatal mortality.[55]

Figure 2.

Hemodynamic response of the fetal pulmonary circulation to intrapulmonary infusion of the selective 5-hydroxytryptamine inhibitor, sertraline, P<0.05, versus baseline (n=16). Sertraline (10 mg) was infused over a 40-minute time period. Infusion of sertraline increased pulmonary vascular resistance. The pulmonary vasoconstrictor response to sertraline was sustained for at least 80 minutes after the completion of the infusion.[54]

Maternal smoking has also been linked to the development of PPHN. It is likely that maternal tobacco smoke exposure causes fetal hypoxia. In guinea pigs[56] and rhesus monkeys, fetal oxygen content was decreased after cigarette smoke exposure.[57] Hence, while cigarette smoking may indirectly increase the risk of PPHN in an infant, an epidemiologic link between cigarette smoking and PPHN remains elusive. Van Marter et al. were unable to link maternal smoking to PPHN,[45] while a subsequent report demonstrated that among infants with PPHN, 64.5% had detectable levels of a nicotine metabolite in their cord blood compared to 28.2% of control infants.[58]

Perinatal

While the perinatal issues that predispose to PPHN are well recognized (Table 1), how each increases the risk of PPHN remains incompletely understood. Among the most well-recognized risk factors for PPHN is meconium staining of the amniotic fluid. Whether PPHN is a direct consequence of meconium aspiration or is a surrogate marker for in utero stress remains unknown. Meconium inactivates surfactant, causes lung inflammation and alveolar hypoxia resulting in pulmonary vasoconstriction. Meconium in the airway leads to obstruction, gas trapping, and lung overdistention and elevation of pulmonary vascular resistance.

Table 1.

Risk factors for the development of PPHN

In the neonatal period, supplemental oxygen may increase pulmonary vascular resistance by increasing oxidative stress. High concentrations of inspired oxygen may potentiate endothelin-1 signaling and diminish eNOS expression.[59] Hyperoxia impairs pulmonary vasodilation caused by inhaled nitric oxide in normal lambs after birth,[60] perhaps by increasing phosphodiesterase type V activity.[61] Superoxide production is increased in experimental models of PPHN.[62] Superoxide anions rapidly combine with nitric oxide to reduce its bioavailability and forms peroxynitrite, a potent oxidant with the potential to produce vasoconstriction and cytotoxicity. Treatment with recombinant human superoxide dismutase (rhSOD) enhances vasodilation after birth.[60,62] SOD restores eNOS expression and function in pulmonary arteries of animals with PPHN,[61] providing still further evidence that increased oxidant stress increases perinatal pulmonary vascular tone.

CONCLUSIONS

PPHN remains a significant source of perinatal morbidity and mortality. The inability to either prevent or treat PPHN optimally confers great importance on early recognition of factors that increase the risk of PPHN. While there is information surrounding factors that might increase the risk of PPHN, knowledge remains incomplete. At present, delivery of infants via Cesarean section without the prior labor seems to pose the single greatest risk for a newborn infant to have PPHN. High maternal body mass index, maternal use of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and maternal diabetes mellitus are additional factors that are associated with an increased risk for PPHN. Recent data suggest that maternal use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors might represent another important risk factor for PPHN. Infants with structural abnormalities of the lung, especially congenital diaphragmatic hernia, are also at increased risk for PPHN. Moreover, any in utero or perinatal insult that causes fetal or neonatal hypoxia will also increase the likelihood of PPHN (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN). PPHN is characterized by abnormal vascular reactivity, cellular proliferation and vascular remodeling. Factors that contribute to the physiologic alterations that characterize PPHN include decreased production of vasodilator agents (nitric oxide, prostanoids) and an increase in endothelin production from the pulmonary endothelium, exposure to high concentrations of supplemental oxygen leading to increases in oxidative stress, activation of signaling pathways such Rho kinase and alterations in calcium-sensitive potassium channel expression. The overall effect is compromised pulmonary vasodilation, extra-pulmonary shunting of blood away from the lung and severe, central hypoxemia.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rudolph A. Distribution and regulation of blood flow in the fetal and neonatal lamb. Circ Res. 1985;57:811–21. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.6.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassin S, Dawes GS, Mott JC, Ross BB, Strang LB. The vascular resistance of the fetal and newly ventilated lung of the lamb. J Physiol. 1964;171:61–79. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teitel DF, Iwamoto HS, Rudolph AM. Changes in the pulmonary circulation during birth-related events. Pediatr Res. 1990;27:372–8. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199004000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawes GS, Mott JC, Widdicombe JG, Wyatt DG. Changes in the lungs of the newborn lamb. J Physiol Lond. 1953;121:141–62. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1953.sp004936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassin S, Dawes GS, Ross BB. Pulmonary blood flow and vascular resistance in immature fetal lambs. J Physiol. 1964;171:80–9. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Assali NS, Kirchbaum TH, Dilts PV. Effects of hyperbaric oxygen on utero placental and fetal circulation. Circ Res. 1968;22:573–88. doi: 10.1161/01.res.22.5.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leffler CW, Hessler JR, Green RS. The onset of breathing at birth stimulates pulmonary vascular prostacyclin synthesis. Pediatr Res. 1984;18:938–42. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198410000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leffler CW, Tyler TL, Cassin S. Effect of indomethacin on pulmonary vascular response to ventilation of fetal goats. Am J Physiol. 1978;235:H346–51. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.234.4.H346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morin F, 3rd, Egan EA, Ferguson W, Lundgren CE. Development of pulmonary vascular response to oxygen. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:H542–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.3.H542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furchgott RF. Studies on relaxation of rabbit aorta by sodium nitrite: The basis for the proposal that the acid-activatable inhibitory factor from bovine retractor penis is inorganic nitrite and the endothelium-derived relaxing factor is nitric oxide. In: Vasodilatation. New York, N.Y.: Raven Press; 1988. pp. 410–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ignarro LJ, Buga GM, Wood KS, Byrns RE, Chaudhuri G. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor produced and released from artery and vein is nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:9265–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amezcua JL, Palmer RM, de Souza BM, Moncada S. Nitric oxide synthesized from L-arginine regulates vascular tone in the coronary circulation of the rabbit. Br J Pharmacol. 1989;97:1019–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb12569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abman SH, Chatfield BA, Hall SL, McMurtry IF. Role of endothelium-derived relaxing factor during transition of pulmonary circulation at birth. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:H1921–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.6.H1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornfield DN, Chatfield BA, McQueston JA, McMurtry IF, Abman SH. Effects of birth-related stimuli on L-arginine-dependent pulmonary vasodilation in ovine fetus. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:H1474–81. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.5.H1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McQueston JA, Cornfield DN, McMurtry IF, Abman SH. Effects of oxygen and exogenous L-arginine on EDRF activity in fetal pulmonary circulation. Am J Physol. 1993;264:H865–71. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.3.H865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiktinsky MH, Morin FC. Increasing oxygen tension dilates fetal pulmonary circulation via endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:H376–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.1.H376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaul PW, Wells LB. Oxygen modulates nitric oxide production selectively in fetal pulmonary endothelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;11:432–8. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.11.4.7522486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinsella JP, Abman SH. Recent developments in the pathophysiology and treatment of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. J Pediatr. 1995;126:853–64. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinsella JP, Truog WE, Walsh WF, Goldberg RN, Bancalari E, Mayock DE, et al. Randomized, multicenter trial of inhaled nitric oxide in severe, persistent pumonary hypertension of the newborn. J Pediatr. 1997;131:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly LK, Porta NF, Goodman DM, Carroll CL, Steinhorn RH. Inhaled prostacyclin for term infants with persistent pulmonary hypertension of refractory to inhaled nitric oxide. J Pediatr. 2002;141:830–2. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.129849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg SJ, Levy RA, Siassi B, Betten J. Effects of maternal hypoxia and hyperoxia upon the neonatal pulmonary vasculature. Pediatrics. 1971;48:528–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levin DL, Levin DL, Hyman AI, Heymann MA, Rudolph AM. Fetal hypertension and the development of increased pulmonary vascular smooth muscle: A possible mechanism for the PPHN infant. J Pediatr. 1976;92:265–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belik J. Myogenic response in large pulmonary arteries and its ontogenesis. Pediatr Res. 1994;36(1 Part 1):34–40. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199407001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belik J, Keeley FW, Baldwin F, Rabinovitch M. Pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H2303–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.6.H2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belik J, Majumdar R, Fabris VE, Kerc E, Pato MD. Myosin light chain phosphatase and kinase abnormalities in fetal sheep pulmonary hypertension. Pediatr Res. 1998;43:57–61. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199801000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belik J, Halayko AJ, Rao K, Stephens NL. Fetal ductus arteriosus ligation.Pulmonary vascular smooth muscle biochemical and mechanical changes. Circ Res. 1993;72:588–96. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McQueston JA, Kinsella JP, Ivy DD, McMurtry IF, Abman SH. Chronic pulmonary hypertension in utero impairs endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Am J Physiol. 1995;37:H288–94. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.1.H288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villamor E, Le Cras TD, Horan MP, Halbower AC, Tuder RM, Abman SH. Chronic intrauterine pulmonary hypertension impairs endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the ovine fetus. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L1013–20. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.5.L1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaul PW, Yuhanna IS, German Z, Chen Z, Steinhorn RH, Morin FC., 3rd Pulmonary endothelial NO synthase gene expression is decreased in fetal lambs with pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L1005–12. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.5.L1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abman S, Accurso F. Acute effects of partial compression of ductus arteriosus on fetal pulmonary circulation. Am J Physiol. 1989;260:H626–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.2.H626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinhorn R, Russell J, Morin FR. Disruption of cGMP production in pulmonary arteries isolated from fetal lambs with pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H1483–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.4.H1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar P, Kazzi NJ, Shankaran S. Plasma immunoreactive endothelin-1 concentrations in infants with persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Am J Perinatol. 1996;13:335–41. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.RosenbergA A, Kennaugh J, Koppenhafer SL, Loomis M, Chatfield BA, Abman SH. Elevated immunoreactive endothelin-1 levels in newborn infants with persistent pulmonary hypertension. J Pediatr. 1993;123:109–14. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81552-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yanagisawa H, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Clouthier DE, Yanagisawa M. Role of Endothelin-1/Endothelin-A receptor-mediated signaling pathway in the aortic arch patterning in mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:22–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yanagisawa H, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Emoto N, Williams SC, Takeda S, et al. Disruption of ECE-1 and ECE-2 reveals a role for endothelin-converting enzyme-2 in murine cardiac development. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1373–82. doi: 10.1172/JCI7447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christou H, Adatia I, Van Marter LJ, Kane JW, Thompson JE, Stark AR, et al. Effect of inhaled nitric oxide on endothelin-1 and cyclic guanosine 5′-monophosphate plasma concentrations in newborn infants with persistent pulmonary hypertension. J Pediatr. 1997;130:603–11. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ivy DD, Kinsella JP, Abman SH. Physiologic characterization of endothelin A and B receptor activity in the ovine fetal pulmonary circulation. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2141–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI117210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldman AP, Tasker RC, Haworth SG, Sigston PE, Macrae DJ. Four patterns of response to inhaled nitric oxide for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Pediatrics. 1996;98:706–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langham MR, Jr, Kays DW, Ledbetter DJ, Frentzen B, Sanford LL, Richards DS. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia.Epidemiology and outcome. Clin Perinatol. 1996;23:671–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reid LR. Diaphragmatic hernia of the liver with review of the literature. Miss Doct. 1951;28:351–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shehata SM, Sharma HS, Mooi WJ, Tibboel D. Pulmonary hypertension in human newborns with congenital diaphragmatic hernia is associated with decreased vascular expression of nitric-oxide synthase. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2006;44:147–55. doi: 10.1385/CBB:44:1:147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keller RL, Tacy TA, Hendricks-Munoz K, Xu J, Moon-Grady AJ, Neuhaus J, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Endothelin-1, pulmonary hypertension, and disease severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:555–61. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200907-1126OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson KL, Zelig CM, Harvey JP, Cunningham BS, Dolinsky BM, Napolitano PG. Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn is associated with mode of delivery and not with maternal use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Am J Perinatol. 2011;28:19–24. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hernandez-Diaz S, Van Marter LJ, Werler MM, Louik C, Mitchell AA. Risk factors for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e272–82. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Marter LJ, Leviton A, Allred EN, Pagano M, Sullivan KF, Cohen A, et al. Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn and smoking and aspirin and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug consumption during pregnancy. Pediatrics. 1996;97:658–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruiz U, Piasecki GJ, Balogh K, Polansky BJ, Jackson BT. An experimental model for fetal pulmonary hypertension.A preliminary report. Am J Surg. 1972;123:468–71. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(72)90201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abman SH, Shanley PF, Accurso FJ. Failure of postnatal adaptation of the pulmonary circulation after chronic intrauterine pulmonary hypertension in fetal lambs. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1849–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI114091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chambers CD, Hernandez-Diaz S, Van Marter LJ, Werler MM, Louik C, Jones KL, et al. Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. New Eng J Med. 2006;354:579–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacLean MR, Deuchar GA, Hicks MN, Morecroft I, Shen S, Sheward J, et al. Overexpression of the 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter gene: Effect on pulmonary hemodynamics and hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2004;109:2150–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127375.56172.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lawrie A, Spiekerkoetter E, Martinez EC, Ambartsumian N, Sheward WJ, MacLean MR, et al. Interdependent serotonin transporter and receptor pathways regulate S100A4/Mts1, a gene associated with pulmonary vascular disease. Circ Res. 2005;97:227–35. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000176025.57706.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Long L, MacLean MR, Jeffery TK, Morecroft I, Yang X, Rudarakanchana N, et al. Serotonin increases susceptibility to pulmonary hypertension in BMPR2-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2006;98:818–27. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000215809.47923.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.MacLean MR. Endothelin-1 and serotonin: Mediators of primary and secondary pulmonary hypertension? J Lab Clin Med. 1999;134:105–14. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(99)90114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morecroft I, Loughlin L, Nilsen M, Colston J, Dempsie Y, Sheward J, et al. Functional interactions between 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors and the serotonin transporter in pulmonary arteries. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:539–48. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.081182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Delaney C, Gien J, Grover TR, Roe G, Abman SH. Pulmonary vascular effects of serotonin and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the late-gestation ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L937–44. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00198.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fornaro E, Li D, Pan J, Belik J. Prenatal exposure to fluoxetine induces fetal pulmonary hypertension in the rat. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1035–40. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-163OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johns JM, Louis TM, Becker RF, Means LW. Behavioral effects of prenatal exposure to nicotine in guinea pigs. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1982;4:365–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Socol ML, Manning FA, Murata Y, Druzin ML. Maternal smoking causes fetal hypoxia: Experimental evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;142:214–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)32339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bearer C, Emerson RK, O’Riordan MA, Roitman E, Shackleton C. Maternal tobacco smoke exposure and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105:202–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Förstermann U. Oxidative stress in vascular disease: Causes, defense mechanisms and potential therapies. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:338–49. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lakshminrusimha S, Russell JA, Steinhorn RH, Ryan RM, Gugino SF, Morins FC, 3rd, et al. Pulmonary arterial contractility in neonatal lambs increases with 100% oxygen resuscitation. Pediatr Res. 2006;59:137–41. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000191136.69142.8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farrow KN, Groh BS, Schumacker PT, Lakshminrusimha S, Czech L, Gugino SF, et al. Hyperoxia increases phosphodiesterase 5 expression and activity in ovine fetal pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2008;102:226–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lakshminrusimha S, Russell JA, Wedgwood S, Gugino SF, Kazzaz JA, Davis JM, et al. Superoxide dismutase improves oxygenation and reduces oxidation in neonatal pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1370–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-676OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]