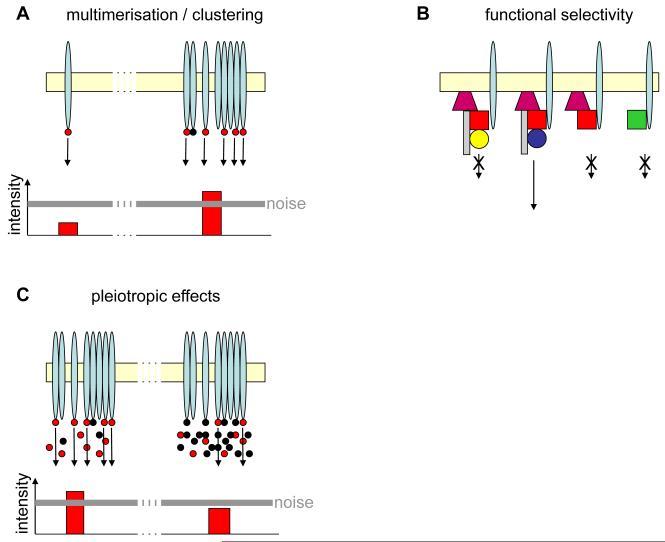

Figure 3.

Examples of how signaling noise shapes cellular signal transduction. (A) Left: The signal (arrow) arising from one signaling receptor (elongated blue oval) at the membrane (beige) is not enough to overcome the threshold created by signaling noise. Right: Receptor multimerization is required to amplify the signal sufficiently to overcome the signaling threshold created by noise from promiscuous PPIs. Red dot: biologically relevant ligand; black dot: biologically nonrelevant ligand. (B) Functional selectivity through formation of multicomponent signaling complexes allows proofreading; a structurally similar but physiologically nonrelevant partner may bind to certain partially assembled components, but only the synergy of a correctly assembled complex (second from left) allows signal transduction to occur. First complex from left and first from right represent stalled complexes misassembled at different stages; second from right represents an incompletely assembled complex. Biologically nonrelevant homologues are indicated by the same shape and different color as the biologically relevant ligand in the correct signaling complex. (C) Grossly changing the concentration of one molecule may influence even signaling pathways for which this molecule is not a biologically relevant component. For example, before overexpression of the biologically nonrelevant ligand (black dot), a sufficient number of the biologically relevant ligand (red dot) could bind to its cognate receptor, initiating an above-threshold signal. After overexpression of the nonrelevant ligand, competition causes the number of biologically relevant ligands bound to the receptor to decrease. As a result, the ensuing signal remains below the noise threshold and cannot trigger a cellular response.