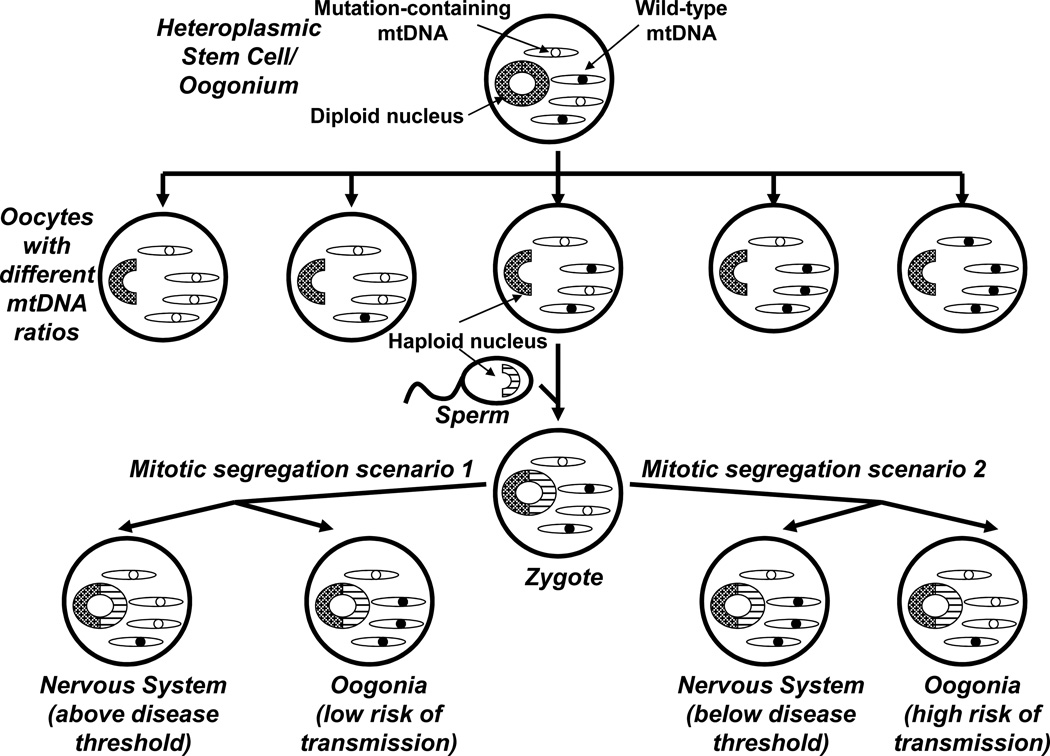

Figure 1. Maternal inheritance, heteroplasmy, mitotic segregation, and threshold effects distinguish mitochondrial genetics from Mendelian genetics.

During embryogenesis a female generates diploid oogonia, which produce haploid oocytes. An oogonium that contains a heteroplasmic mtDNA mutation may produce oocytes with different mtDNA mutation burdens; oocytes with low mutation levels are less likely to produce disease-affected offspring, while oocytes with high mutation levels are more likely to do so. Fertilization then produces a zygote whose mtDNA comes from the ooctye, with little or no sperm contribution. Because of mitotic segregation, heteroplasmic mtDNA mutations may end up having unequal tissue distributions. In scenario 1, the developing individual has a high mutational burden in the nervous system and low mutational burden in their germ cells. This individual has an elevated neurologic disease risk (surpasses the threshold) and low risk of passing on disease risk (if the individual is a male, there is no chance of passing on disease risk). In scenario 2, the developing individual ends up with a low mutational burden in the nervous system and high mutational burden in their germ cells. This individual does not have an elevated neurologic disease risk (below the threshold), but if the individual is female there is an increased risk of passing on the mtDNA mutation. Therefore, although mtDNA is maternally inherited diseases influenced by mtDNA-inheritance can appear sporadic.