Abstract

The success of first-line antiretroviral therapy can be challenged by the acquisition of primary drug resistance. Here we report a case where baseline genotypic resistance testing detected resistance conferring nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI)-associated mutations, but no primary mutations for protease inhibitor (PI). Subsequent PI-based HAART with boosted saquinavir led to virological treatment success with persistently undetectable viral load. After treatment simplification from saquinavir to an atazanavir based PI-therapy and no change in backbone therapy rapid virological breakthrough occurred. Retrospective analysis displayed preexisting gag cleavage site mutations which may have reduced the genetic barrier in a clinical relevant manner in combination with the already existing NRTI resistance mutations. Alternatively, this effect could be explained with a different antiviral potency for the respective PIs used.

Keywords: transmitted resistance, Drug Resistance, Human immunodeficiency virus I, T215 D

Introduction

The development of drug resistance is a major concern for successful treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection due to selection of genotypic mutations that may lead to reduced phenotypic drug susceptibility. With common resistance tests minor variants carrying drug resistance mutations in HIV, which may emerge under antiretroviral drug pressure and eventually lead to therapy failure, may not be detected.

Large surveys have estimated that 10 to 25% of drug-naïve infected patients harbour HIV-1 with mutations for resistance to at least one antiretroviral drug class [1].

In the area of Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany, the rate of transmitted primary drug resistance mutations was found to be about 10% between 2001-2005 [2]. Transmission of drug resistant variants from patients with resistant viruses takes place in only about 20% to 35% of cases in comparison to drug-sensitive virus. Recent estimations assume a lifelong persistence of detectable transmitted drug resistant mutants [3].

Drug resistance mutations confer a fitness cost, because they only occur under drug selection pressure and do not occur as natural polymorphisms. Consequently, the detection rate of viruses with transmitted resistance mutations is low [4]. Nevertheless, highly resistant variants may persist for years in the host [5]. In chronic HIV infection drug resistance can evolve in the presence of ongoing viral replication under the selective pressure of antiretroviral drugs. Frequently, these acquired drug resistance mutations may reduce viral replication capacity [6]. Recently, it was shown that in terms of resistance to protease inhibitors, mutations outside the viral protease can also be selected during treatment failure and increase the level of resistance. These mutations are located in the HIV gag cleavage sites, which are the natural substrates of the viral protease during the maturation process leading to the formation of infectious particles and confer resistance to protease inhibitors by an increased processing rate of the precursor gag proteins [7].

In general, primary genotypic drug resistance in an antiretroviral-naïve patient is recognized as a transmitted infection with HIV strains with mostly single drug resistance mutations in the viral reverse tanscriptase and protease. These variants usually display a weak, if any, in culture measurable resistance. It is hypothesized that once resistant viruses are transmitted, they quickly revert most of the mutations to wildtype due to the impaired fitness of viruses with drug resistance, thereby explaining why most often only single mutations but not multiple mutations are detected. As a drug resistance mutation usually occurs through exchange of one single base pair in a codon, revertance of such drug resistance cannot be traced. However, thymidin analogue mutations in codon 215 require a change of two base pairs to lead to the resistant variant T215F/Y. Drug-withdrawal leads to a phenotypical wild-type (wt) with a different amino acid composition like T215D/C/E/L/S. Again under antiretroviral therapy these revertants can quickly mutate back to the drug-resistant variant [8]. The acquisition of several mutations including M41L, D67N, K70R, L210W, T215F/Y and K219Q/E may lead to different levels of resistance to zidovudine and other NRTIs depending on the particular combination [9].

The detection of resistance mutations and their different interpretation in treatment naïve patients compared to therapy experienced patients is essential for the management of HIV-infected patients. But to date there is no resistance interpretation tool for therapy naïve patients.

Case report

Here we describe the case of a 33-year-old female (W), first documented to be human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1, Subtyp B) seropositive in August 2006, while presenting with pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and a wasting-syndrom. Upon initial presentation the patient had 60 CD4 cells/μl and more than 500000 HIV-1 RNA copies/ml (limit of linearity of the viral load assay Versant bDNA, Siemens, Germany). The patient also reported weakness for the last year and an episode of herpes zoster for 3 weeks, but no test for HIV-1 infection had been performed at that time. The last negative HIV-test was obtained in 2004. HIV- tests had been performed regularly since her husband had a documented HIV-infection since 1985, following treatment with blood products he received for therapy of congenital haemophilia A (AXSYM HIV combo, ABBOTT, Germany).

Genotypic resistance testing identified M41L and T215D as resistance mutations within the reverse transcriptase and the secondary mutations I13V, L63P within the protease gene regions. Restrospectivly, additional cleavage site mutations L449V and S451N at the C-teminal gag cleavage site p1/p6-gag were found.

Table 1 shows the resistance-related mutations detected in the baseline samples as well as those found in the samples tested later on, according to the IAS resistance panel http://www.iasusa.org/resistance_mutations/index.html. Resistance interpretation systems like the Trugene HIV-1 with guidelines 10.0 were used in these analyses.

Table 1.

Antiretroviral therapy and drug resistance mutation over time in study subjects

| Patient | Year | Antiretroviral therapy | mutations associated with resistance | Virus load Copies/ml |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 1993 | AZT | n.d. | ||

| 1995 | AZT, 3TC | ||||

| 12/1997 | d4T, 3TC | ||||

| 1999 | 4700 | ||||

| 07/2004 | RT: M41L, M184V, T215Y, (T39A, V60I, D121Y, I135T, I142V1, D177G, V179I, T200A, Q207E, L214f, L228H, Q334H) | 26929 | |||

| PR: L63P, I13V, (V3I, K14R, S37N) | |||||

| CS p1/p6-gag: L449V, S451N | |||||

| 08/2004 | ATV/r, EFV | ||||

| 01/2005 | < 50 | ||||

| 04/2005 | ATV/r, EFV, 3TC | < 50 | |||

| W | 08/2006 | RT: M41L, T215D, (T39A, V60I, D121Y,135T,N137S,I142V, S162C, I202I/V, Q207E/K, l214F, l228H) | > 500.000 | ||

| PR: L63P, I13V, (E35D, S37N/S, S37N, V3I) | |||||

| CS p1/p6-gag: L449V, S451N | |||||

| 09/2006 | TVd, INV/r | ||||

| 10/2008 | TVd, ATV/r | < 40 | |||

| 11/2008 | 1381 | ||||

| 12/2008 | 132 | ||||

| 02/2008 | 8515 | ||||

| 03/2009 | RT: M41L, T215D, (T39A,V601I D121Y, K122E,135T,N137S,I142V S162C, I202IV, Q207E/K, L214F, L228H, V245M, A272P, T286A, E297K) | ||||

| PR: L63P, I13V, E35D | |||||

| CS p1/p6-gag: l449V, S451N | |||||

| 04/2009 | NVP, DRV/r | ||||

| 06/2009 | < 40 | ||||

| 11/2009 | < 40 | ||||

M = husband/suspected source of infection, W = case-patient

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) with tenofovir (TDF), emtricitabin (FTC) once daily and saquinavir 1000 mg twice daily boosted by ritonavir was initiated 2 months after initial HIV-diagnosis in September 2006. The treatment resulted in a > 2-log decrease in HIV-1 RNA load at week 4, a further decline in viraemia to 56 copies/ml after 3 months of HAART and subsequent complete suppression under detection limit for 19 months untill October 2008. The CD4 cell count in paralell increased to 308 cells/μl and 30%, respectively. During the treatment period one episode with a blip of 145 copies/ml occurred. In Oktober 2008 HAART was simplified to tenofovir, emtricitabin and ritonavir-boosted atazanavir in order to have a once-daily therapy. Within four weeks after initiation of this regimen the viral load increased to 1381 copies/ml. Viral load decreased to 132 copies/ml in a control but raised again to 8515 copies/ml in February 2008.

The virological treatment failure prompted the second genotypic drug resistance test which revealed the same NRTI-associated and gag cleavage site mutations as in the resistance test prior to commencing ART, namely M41L and T215D with limited susceptibility for AZT, d4T and tenofovir (Table 1). The regimen was changed again in April 2009 to ritonavir boosted darunavir 800 mg and nevirapine 400 mg once daily. Under the new regimen a skin rash occured six days after treatment initiation. Symptoms were regressive under intake of cortison and vanished after 12 days. Two months after changing therapy plasma viral load decreased again below the limit of detection.

The 42 years-old husband (M) having a HIV-infection since 1985 due to treatment of haemophilia A, CDC status A2, received his first antiretroviral therapy, which was AZT-monotherapy, in 1993. In 1995 he was treated with additional lamivudin (3TC). A new regimen was startet in 1997 with d4T and 3TC. Because of lipoatrophy and ongoing viral replication under ART, HIV-therapy was changed to ritonavir-boosted atazanavir and efavirenz in 2004 after screening for drug resistance. Genotypic resistance testing in the husband showed no NNRTI and no PI mutations but the following NRTI mutations: M41L, M184V and T215Y. Despite a favourable immunological respose under the past antiretroviral therapies, the viral load became undetectable for the first time in 2005 after the switch to ritonavir-boosted atazanavir and efavirenz had occurred. CD4 cell counts after changing antiretroviral therapy remained stable with 466 cell/μL (23%). Comparing the findings of the genotyping resistance tests of the infected couple, we found the same resistance mutations in both individuals, except for the absence of M184V and the presence of the "revertant" T215D in place of the T215Y resistance mutation in the HIV infected wife. No resistance mutations could be found in the protease gene despite virological failure under atazanavir therapy in the wife but the same two gag cleavage site mutations (L449V, S451N) remained.

The husband was also coinfected with hepatitis B and C. Therefore, 3TC was added to the antiretroviral therapy for HBV viremia in the same year. HCV infection was successfully treated with PEG-interferon-alpha and weight-based Ribavirin therapy in 2002. No chronic hepatitis was diagnosed in the wife.

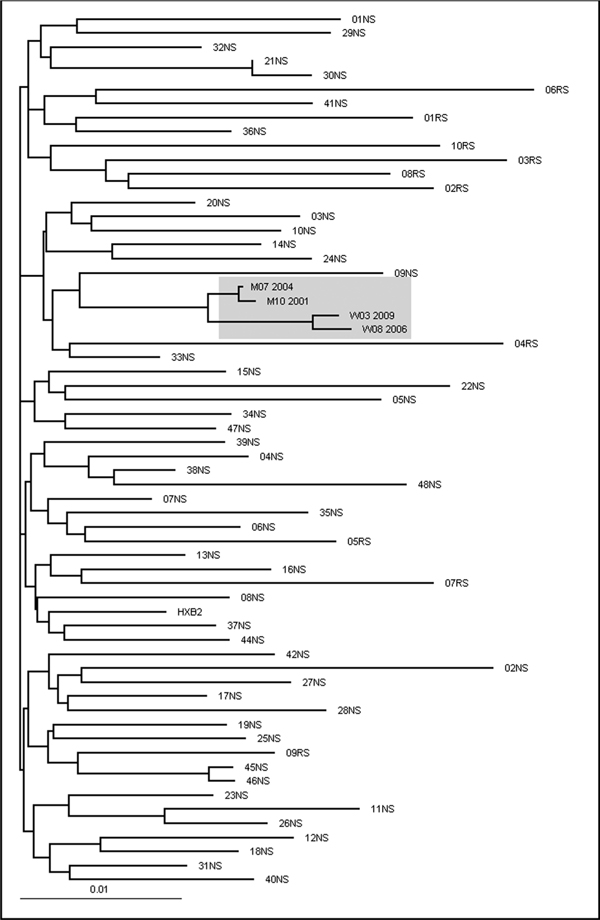

Phylogenetic analysis using a pool of most similar HIV-1 sequences obtained in the same years from the same area confirmed that the viruses in these patients were closer related to each other compared to any other virus in the local database with a similarity score of 97,5%. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree shows the close relationship between patient W and M sequences. Phylogenetic analysis was conducted on a data set of 62 HIV-1 polymerase sequences aligned through MutExt and ClustalX, including the four sequences available from patients W and M. The 48 most similar sequences to W03_2009 (01NS-48NS) and 10 per chance selected sequences (RS) from patients, obtained from the same geographic area during the same time period, were selected from a total of 6400 sequences in the Arevir database [21]. Patient W and Patient M sequences are indicated by W and M followed by the month and year of the sampling date. HXB2 is the wild type reference strain.

Discussion

Here we report the transmission of the thymidine analogue mutations (TAM) T215Y and M41L to an antiretroviral naïve spouse of an HIV-infected haemophiliac patient, who subsequently developed virological failure after simplifying her therapy to a boosted atazanavir based therapy. The NRTI-resistance mutations M41L and T215Y were most likely transmitted from her husband, who had developed these specific mutations under a previous phase of AZT monotherapy in 1993. These TAM mutations are scored by most of the interpretation systems to confer an intermediate level resistance to AZT, d4T and a low level resistance to ddI, ABC and TDF. Some interpretations systems rank TDF to an intermediate level. One must be aware that the interpretation systems are developed for therapy experienced patients and therefore the risk of the above mentioned resistance mutations is underestimated in naïves. Phylogenetic analysis clearly indicates a common origin for the viruses and makes it very probable that transmission occurred from husband to wife.

We believe, that the transmission of the M41L/T215Y mutants were due to AZT administration in 2004 while M184V occurred under treatment with lamivudine. The last negative HIV-Test of the wife took place in 2004. The T215D-strain occurred as a revertant from T215Y consequently in the absence of drugs in the wife; T215D is as fit as the wild-type virus in cell culture assays in the absence of the drug, but retains the potential for rapid emergence of high-level zidovudine resistance. T215 D/S/C/E/I/V are transitions between wild type virus and resistant mutants carrying Y or F. The presence of T215D suggests the presence of clinically relevant T215Y minorities.

Interestingly, fitness determinations based on growth competition experiments in cell culture showed a value of 85% fitness for T215Y, 80% for M41L and a similar fitness for the double mutant M41L/T215Y [10,11] relative to the wildtype in the absence of drugs. Viruses carrying the T215Y mutation emerge more frequently than T215F while showing a faster replication kinetics and greater relative fitness in comparison with T215F mutants in the absence or presence of zidovudine. Moreover, T215Y mutants show greater infectivity than wildtype HIV-1 over a range of AZT concentrations [12].

The evaluation of differential transmission of HIV1 strains harbouring mutations in RT in newly infected individuals compared with the prevalence in the potential transmitter population showed that the prevalence of the 3TC-resistance associated mutation M184V was only 3%, compared to TAMs 6,7% and NNRT-associated mutations 7,4%. All this suggests that reductions in viral fitness of M184V-containing HIV-1 strains may partially affect rates of viral transmission [13]. In the absence of therapy the decreased fitness of viruses carrying T215Y/F, K70R, or M184V is reflected by the pressure to mutate during the evolution of transmitted HIV-1 resistance mutations [14]. The M184V mutation develops quickly after initiation of therapy with 3TC and confers high-level resistance to this drug and to FTC. ABC and 3TC are able to preserve M184V in mixed dual infections consisting of wildtype viruses and clinical isolates that contain the M184V mutation [15,16]. Unlike TAMs, M184V reverts to wild-type virus when lamivudine is eliminated from antiretroviral regimens [17]. This mutation confers a low fitness and also reduces the risk of viral transmission [13], which might explain the absence of M184V in the wife's strain. Usually in the first period of infection CD4 T-cell counts remain stable, later the likelihood of slowly decreasing CD4 T-cell counts increases. The rates were higher in those subjects infected with resistant viruses with lower replication capacity [18]. We concluded from the anamnestic data, that the transmission took place between August 2004 and January 2005. Under consideration of the low CD4 count at initial presentation a very rapid course of HIV-infection needs to be stated. Indeed, the patient progressed to a CD4 count of 60/ml already 1-2 years after HIV-1-infection.

Most apparently the therapy failure resulted from the archieved NRTI resistance for M41L, (probably on the M184V) and the T215D mutation which was already visible in the blood before virological failure occurred after switching from invirase to atazanavir, both administered as ritonavir-boosted PIs, while tenofovir and emtricitabin remained unchanged as backbone NRTI combination. This further questions the efficacy of atazanavir in combination with an only intermediate active NRTI-backbone. Adherence problems or use of proton-pump inhibitors were denied by the patient. The new antiretroviral regimen with darunavir/r and nevirapine (2 fully active drugs from 2 divergent drug classes) lead to maximal viral load suppression in less than 8 weeks. The question remains whether the presence of mutants in sanctuary sites carrying M41L, M184V and T215Y contributed to the viral rebound alone or together with effects conferred by the retrospectively detected gag cleavage site mutations, while PI mutations in the protease gene were not present. The selection of a PI-based regimen in case of detection of NRTI mutations is in line with the European resistance guidelines. NNRTI-based regimens are considered to have a too low genetic barrier in first line therapy settings. On the contrary in all first-line studies, cases of protease inhibitor failures are described in absence of detectable protease inhibitor resistance mutations. In this content, mutations in the gag-region, the natural substrate of the viral protease, have recently gained importance and has been shown to contribute directly to protease inhibitor resistance [7]. Interestingly, the gag cleavage site mutation S451N was classified as a natural polymorphism [19], whereas cleavage site mutation L449V was found to be significantly accumulated in PI resistant HIV isolates [20]. Therfore, it could be speculated that in our case study this mutation possibly contributed to protease inhibitor failure, although the impact of these gag cleavage site mutations may vary between different PIs. Clearly, in this case, the boosted protease inhibitors saquinavir and darunavir were able to suppress viral replication with the TDF/FTC backbone, whereas this was not the case for atazanavir/r. Although recently drug-resistance related mutations in the HIV gag-region have been described, their respective impact on virological treatment failure is not yet fully understood. Resistance testing is performed routinely at treatment baseline and some resistance tests include the sequencing of an important part of gag-region. But mutations in the gag-region are so far not considered in any resistance interpretation system. Further analyses are required and may lead to routine resistance testing of the gag-region before starting antiretroviral therapy.

References

- Geretti AM. Epidemiology of antiretroviral drug resistance in drug-naïve persons. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:22–32. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328013caff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagir A, Oette M, Kaiser R. et al. Trends of prevalence of primary HIV drug resistance in Germany. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:843–848. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pao D, Andrady U, Clarke J, Dean G, Drake S, Fisher M, Green T. et al. Long-term persistence of primary genotypic resistance after HIV-1 seroconversion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:1570–1573. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200412150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh Brown AJ, Frost SD, Mathews WC, Dawson K, Hellmann NS, Daar ES, Richman DD. et al. Transmission fitness of drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus and the prevalence of resistance in the antiretroviral-treated population. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:683–686. doi: 10.1086/367989. Epub 2003 Jan 2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little SJ, Frost SD, Wong JK, Smith DM, Pond SL, Ignacio CC, Parkin NT. et al. Persistence of transmitted drug resistance among subjects with primary human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 2008;82:5510–5518. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02579-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammano F, Trouplin V, Zennou V, Clavel F. Retracing the evolutionary pathways of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to protease inhibitors: virus fitness in the absence and in the presence of drug. J Virol. 2000;74:8524–8531. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.18.8524-8531.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhuis M, van Maarseveen NM, Lastere S, Schipper P, Coakley E, Glass B, Rovenska M, de Jong D, Chappey C, Goedegebuure IW, Heilek-Snyder G, Dulude D, Cammack N, Brakier-Gingras L, Konvalinka J, Parkin N, Kräusslich HG, Brun-Vezinet F, Boucer CA. A novel substrate-based HIV-1 protease inhibitor drug resistance mechanism. PLoS Med. 2007;4(1):e36. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Mendoza C, del Romero J, Rodriguez C, Corral A, Soriano V. Decline in the rate of genotypic resistance to antiretroviral drugs in recent HIV seroconverters in Madrid. Aids. 2002;16:1830–1832. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209060-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Picado J, Martinez MA. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitor resistance mutations and fitness: a view from the clinic and ex vivo. Virus Res. 2008;134:104–123. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan PR, Kinghorn I, Bloor S, Kemp SD, Najera I, Kohli A, Larder BA. Significance of amino acid variation at human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase residue 210 for zidovudine susceptibility. J Virol. 1996;70:5930–5934. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5930-5934.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan PR, Bloor S, Larder BA. Relative replicative fitness of zidovudine-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates in vitro. J Virol. 1998;72:3773–3778. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3773-3778.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Giguel F, Hatano H, Reid P, Lu J, Kuritzkes DR. Fitness comparison of thymidine analog resistance pathways in human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2006;80:7020–7027. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02747-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner D, Brenner B, Wainberg MA. Decreased rates of transmission of drug-resistant HIV-1 strains of drug-resistant HIV-1 strains containing the M184V mutation in reverse transcriptase. Antivir Ther. 2003;7:143. [Google Scholar]

- Bezemer D, de Ronde A, Prins M, Porter K, Gifford R, Pillay D, Masquelier B. et al. Evolution of transmitted HIV-1 with drug-resistance mutations in the absence of therapy: effects on CD4+ T-cell count and HIV-1 RNA load. Antivir Ther. 2006;11:173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan PR, Stone C, Griffin P, Najera I, Bloor S, Kemp S, Tisdale M. et al. Resistance profile of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase inhibitor abacavir (1592U89) after monotherapy and combination therapy. CNA2001 Investigative Group. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:912–920. doi: 10.1086/315317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julias JG, Boyer PL, McWilliams MJ, Alvord WG, Hughes SH. Mutations at position 184 of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 reverse transcriptase affect virus titer and viral DNA synthesis. Virology. 2004;322:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svedhem V, Lindkvist A, Lidman K, Sonnerborg A. Persistence of earlier HIV-1 drug resistance mutations at new treatment failure. J Med Virol. 2002;68:473–478. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant RM, Barbour JD, Wrin T, Warmerdam M, Hellmann NS, Kahn JO, Petropoulos CJ. et al. Transmission of drug resistant HIV-1 exhibiting lower replication capacitiy is associated with higher CD4 cell counts. Antivir Ther. 2002;7:41. [Google Scholar]

- Verheyen J, Knops E, Kupfer B, Hamouda O, Somogyi S, Schuldenzucker U, Kaiser R, Pfister H, Kücherer C. Prevalence of C-Terminal gag cleavage site mutations in HIV from therapy -naïve patients. J Infect. 2009;58(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheyen J, Litau E, Sing T, Däumer M, Balduin M, Oette M, Fätkenheuer G, Rockstroh JK, Schuldenzucker U, Hoffmann D, Pfister H, Kaiser R. Compensatory mutations at the HIV cleavage sites p7/p1 and p1/p6-gag in therapy -naïve and therapy-experienced patients. Antivir Ther. 2006;11(7):879–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roomp K, Beerenwinkel N, Sing T, Schülter E, Büch J, Sierra-Aragon S, Däumer M, Hoffmann D, Kaiser R, Lengauer T, Selbig J, Arevir. Proceedings 3rd Int. Workshop on Data Integration in the Life Sciences (DILS), Springer; 2006. A Secure Platform for Designing Personalized Antiretroviral Therapies Against HIV. [Google Scholar]