Abstract

Background:

Lichen planus (LP) is a mucocutaneous disease that is relatively common among adult population. LP can present as skin and oral lesions. This study highlights the prevalence of oral, skin, and oral and skin lesions of LP.

Aims:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of oral, skin, and oral and skin lesions of LP from a population of patients attending the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiodiagnosis, Pushpagiri College of Dental Sciences, Tiruvalla, Kerala, India.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was designed to evaluate the prevalence of oral, skin, and oral and skin lesions of LP. This is a ongoing prospective study with results of 2 years being reported. LP was diagnosed on the basis of clinical presentation and histopathological analysis of mucosal and skin biopsy done for all patients suspected of having LP. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS (Statistical package for social sciences) software version 14. To test the statistical significance, chi-square test was used.

Results:

Out of 18,306 patients screened, 8,040 were males and 10,266 females. LP was seen in 118 cases (0.64%). Increased prevalence of LP was observed in middle age adults (40–60 years age group) with lowest age of 12 years and highest age of 65 years. No statistically significant differences were observed between the genders in skin LP group (P=0.12) and in oral and skin LP groups (P=0.06); however, a strong female predilection was seen in oral LP group (P=0.000036). The prevalence of cutaneous LP in oral LP patients was 0.06%.

Conclusion:

This study showed an increased prevalence of oral LP than skin LP, and oral and skin LP with a female predominance.

Keywords: Lichen planus, mucocutaneous, precancerous

Introduction

Lichen planus (LP) is a chronic dermatologic disease that is relatively common among our population. It was first described by a British physician Erasmus Wilson in 1869.[1,2] It is most common among middle-aged adults with women predominance (3:2) ratio over men.[1,2] This article focuses on the prevalence of oral, skin, and oral and skin lesions of LP.

Materials and Methods

A study was conducted in the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiodiagnosis, Pushpagiri college of Dental Sciences, Tiruvalla, Kerala. This is an ongoing study, and results of 2 years are being reported (June 2008 to June 2010). A total of 18,306 subjects who visited the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology for diagnosis of various oral complaints over a period of 2 years were interviewed and clinically examined for oral, skin, and oral and skin lesions of LP.

LP was diagnosed on the basis of clinical presentation, and confirmation was done through histopathological analysis of mucosal and skin biopsy done for all patients suspected of having LP. A pilot study of 100 randomly selected individuals was carried out to determine the feasibility of the study and the amount of time required for examination of each subject. Data obtained were recorded in a proforma which was later transferred for statistical analysis done using SPSS (Statistical package for social sciences) software version 14.

Inclusion criteria

Patients in the age group (10–70 years) were included in the study.

Both men and women participated in this study.

Exclusion criteria

Lesions mimicking oral LP, e.g., lichenoid reaction secondary to dental amalgam restorations were excluded from the study.

Lesions mimicking oral and skin LP but not confirmed as oral and skin LP through biopsy were also excluded from the study.

Results

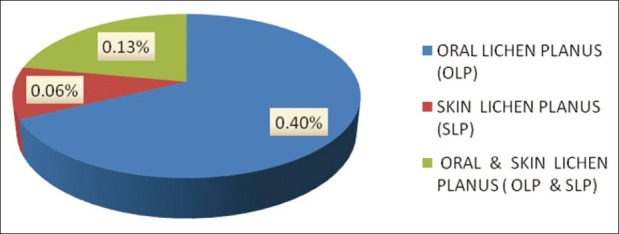

Out of 18,306 patients screened 8,040 (43.9%) were males and 10,266 (56%) females, with ages ranged between 10 and 70 years. From 18,306 patients screened, LP prevalence was (0.64%) with oral lichen planus (OLP) prevalence was (0.4%), skin lichen planus (SLP) was (0.06%), and OLP and SLP was (0.13%) [Figure 1]. Lesions mimicking oral and skin LP but not confirmed as LP through biopsy were 0.1%.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of oral, skin, oral and skin lichen planus in the study population

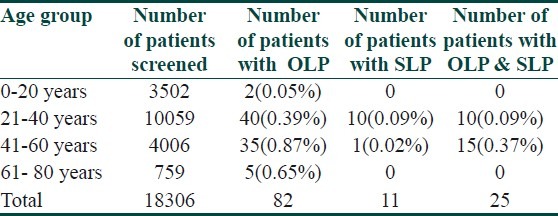

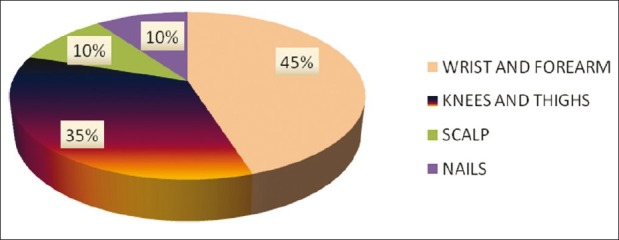

Among the three categories of LP (OLP, SLP, and OLP and SLP), there was a strong female predominance (P=0.000036) in OLP [Table 1]. No significant differences between the genders were seen in SLP, and OLP and SLP categories of LP. Age wise distribution of LP (oral, skin, and oral and skin LP) is presented in Table 2. Among the age groups, highest peak of prevalence of oral, skin, and oral and skin LP was observed in 21–40 and 41–60 year age groups; 12 years was the lowest age of a patient with LP (oral LP) and 65 years was the highest in our study. Intraorally, LP was seen predominantly affecting the buccal mucosa 45%, followed by gingiva 25%, tongue 15%, labial mucosa 10%, and soft palate 5% [Figure 2]. Extraorally, wrist and forearm were affected most often 45%, followed by knees and thighs 35%, scalp 10%, and nails 10% [Figure 3].

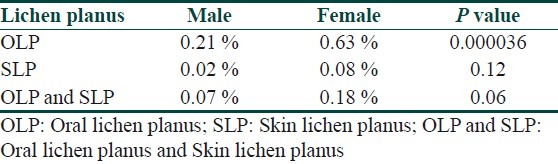

Table 1.

Male:female ratio of patients with oral, skin, and oral and skin LPs

Table 2.

Age wise distribution of lichen planus—oral, skin, and oral and skin LP

Figure 2.

Intraoral site of involvement of lichen planus

Figure 3.

Extraoral site of involvement of lichen planus

Discussion

Lichen planus derives its name “lichen” as it looked like lichens growing on the rock and planus is for flat.[2–4] LP may involve various mucosal surfaces either independently or concurrently (oral, skin, and oral and skin lesions). Oral form may precede or accompany the skin lesions or it may be the only manifestation of the disease.[4] Prevalence of skin LP in general population is 0.9–1.2% and prevalence of oral LP is reported between 0.1% and 2.2%.[4] In our present study, prevalence of skin LP was 0.06% and oral LP 0.4%.

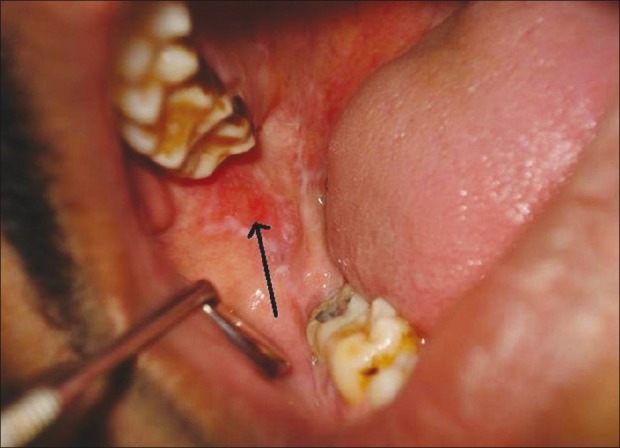

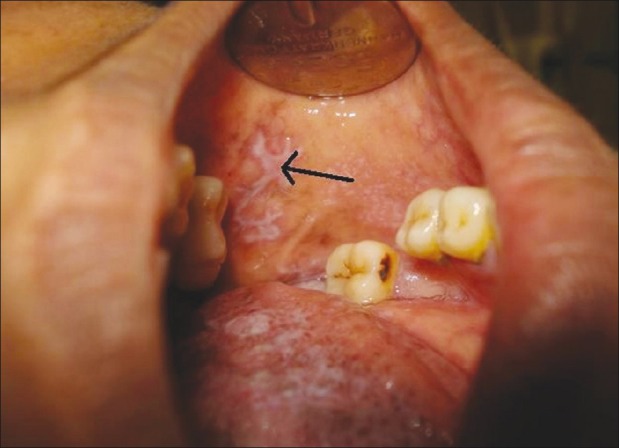

Shklar and Mc Carthy[3,5] have reported the following distribution of oral lesions: buccal mucosa 80%, tongue 65%, lips 20%, gingiva, floor of mouth, and palate less than 10%. Any site in the oral cavity may be involved, but the buccal mucosa and gingiva are the most commonest sites.[6] In our present study, lesions of oral LP were seen mostly on buccal mucosa 45% followed by gingiva 25%, tongue 15%, labial mucosa 10%, and soft palate 5% Figure 2. Clinically, oral LP appear in two major forms—erosive oral LP and nonerosive oral LP.[1,2] Erosive form appears as a central area of erythema with peripheral radiating white striae[1–3] [Figure 4] and nonerosive form or the reticular variety is characterized by the presence of Wickham striae [Figure 5].[1,3] Erosive variety is of great concern to clinician as well as to the patient as patient often experiences burning sensation in the involved areas; moreover, erosive form has an higher potential for malignant transformation[3,7] (0.3%–3%). In our present study, patients who reported with a chief complaint of burning sensation, majority of them had erosive LP and malignant transformation rate was 1%. Nonerosive LP was detected on routine examination.

Figure 4.

Intraoral photograph of a patient showing erosive lichen planus in the buccal mucosa

Figure 5.

Intraoral photograph of a patient showing reticular variety of lichen planus in the buccal mucosa

Conclusion

LP can present as skin and oral lesions. This study shows an increased prevalence of oral LP in (40-60 year) age group with a female predominance. Lesions of oral LP especially the erosive variety need to be monitored carefully as it has a higher risk for transformation into squamous cell carcinoma.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Dermatological diseases. In: Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE, editors. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. pp. 680–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jontell M, Holmstrup P. Red and white lesions of the oral mucosa. In: Green berg MS, Glick M, Ship JA, editors. Burket's Oral Medicine. 11th ed. Hamilton: BC Decker Inc; 2008. pp. 90–1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajendran R. Diseases of the skin. In: Rajendran R, Sivapathasundharam, editors. Shafer's Text book of Oral Pathology. 6th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2009. pp. 799–803. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghom AG. Oral Premalignant lesions and conditions. In: Ghom AG, editor. Text of Oral Medicine. 2nd ed. Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 2010. p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mc Carthy PL, Shklar G. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1980. Diseases of the Oral mucosa. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlino P, Di Felice R, Samson J, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Fiore Donno G. Lichen planus. Clinical diagnosis, epidemiology and pathogenesis. Dent Cadmos. 1991;59:34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang M, Zhang W, Chen Y, He Z. Malignant transformation of oral lichen planus-a retrospective study of 23 cases. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:235–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]