Abstract

Background

Surveys from the USA, Australia and Spain have shown significant inter-institutional variation in delivery room (DR) management of very low birth weight infants (VLBWI, < 1500 g) at birth, despite regularly updated international guidelines.

Objective

To investigate protocols for DR management of VLBWI in Germany, Austria and Switzerland and to compare these with the 2005 ILCOR guidelines.

Methods

DR management protocols were surveyed in a prospective, questionnaire-based survey in 2008. Results were compared between countries and between academic and non-academic units. Protocols were compared to the 2005 ILCOR guidelines.

Results

In total, 190/249 units (76%) replied. Protocols for DR management existed in 94% of units. Statistically significant differences between countries were found regarding provision of 24 hr in house neonatal service; presence of a designated resuscitation area; devices for respiratory support; use of pressure-controlled manual ventilation devices; volume control by respirator; and dosage of Surfactant. There were no statistically significant differences regarding application and monitoring of supplementary oxygen, or targeted saturation levels, or for the use of sustained inflations. Comparison of academic and non-academic hospitals showed no significant differences, apart from the targeted saturation levels (SpO2) at 10 min. of life. Comparison with ILCOR guidelines showed good adherence to the 2005 recommendations.

Summary

Delivery room management in German, Austrian and Swiss neonatal units was commonly based on written protocols. Only minor differences were found regarding the DR setup, devices used and the targeted ranges for SpO2 and FiO2. DR management was in good accordance with 2005 ILCOR guidelines, some units already incorporated evidence beyond the ILCOR statement into their routine practice.

Keywords: delivery room management, preterm, neonate, VLBWI, guidelines, surfactant, oxygen, saturation, monitoring

Background

Survival of very low birth weight infants (VLBWI, birth weight less than 1500 g) is dependent on professional perinatal management [4]. For successful delivery room (DR) management various aspects of the postnatal adaption process need to be considered such as the support of the thermal adaptation, airway management, breathing, circulation and metabolism [17]. The consistent provision of high quality care in a field as challenging and stressful as neonatal resuscitation has been shown to be improved by the adherence to standardized protocols [26]. An up to date, evidence based protocol and modern set-up of the DR, recently referred to as „the delivery room neonatal care unit" (DR NICU, as by Vento et al.), helps ensure a successful and coordinated, patient centred team effort [12,28]. Thanks to the extensive research interest in neonatal resuscitation, good quality evidence has become available from an increasing number of large randomized controlled trials on almost all fields of DR management over the course of the past decade [9,29].

Different international organizations have dedicated their work towards the provision of up to date recommendations on the DR management of neonates, namely the European Resuscitation Council [3] and the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation Council [7]. In seeking to provide up to date recommendations on the management and on the best equipment used during resuscitation, ILCOR engages more than 500 physicians, collaborating to evaluate the best available evidence from over 20.000 papers in search of the best evidence. These recommendations are distributed through the scientific literature [1]. Furthermore, the practice of DR management is widely being taught in various internationally recognized training programmes (neonatal advanced life support = NALS, neonatal resuscitation program = NRP) (see Leone [10]).

Despite the above efforts to standardize delivery room management of VLBWI neonates, national surveys from Australia, the USA, Italy and Spain have shown wide and significant inter-institutional variations in DR management of VLBWIs. These were found regarding, for instance, the equipment used for resuscitation and for monitoring, or regarding the targeted parameters during resuscitation [8,10,13,27].

The aim of our study was to investigate the current state of DR management of infants with birth weight < 1500 g at birth in German speaking countries (Germany (DE), Austria (AU) and Switzerland (CH)). We wanted to know to which extent the above named recommendations were incorporated in local treatment protocols and whether there was a differences in the implementation between the countries and between academic and non-academic hospitals.

Methods

We conducted a questionnaire survey on DR management of German, Austrian and Swiss neonatal units. Between October and December 2008 a total of 249 units were approached (DE: 193, AU: 14 CH: 42). The questionnaire was developed in our clinic and pretested on our Department (Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany). Elements from published questionnaires were incorporated to ensure comparability to published data from other surveys [10].

Questionnaire

The questionnaire contained four sections:

• Characterization of the institution: Information was obtained on the level of care and the teaching status of the institution, number of in house births below 1500 g/year, presence of 24 hr neonatal in house service and number of admissions to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) per year. We distinguished between academic children's hospitals or academic teaching hospitals and non-academic children's hospitals.

• Perinatal management: information on late cord clamping, thermal management in DR, and presence of a designated resuscitation area, protocols or guidelines for DR management.

• DR management equipment: Types of ventilator equipment used, means of non-invasive respiratory support systems (bags, T-piece resuscitators, ventilators), use of CO2-detectors, oxygen blenders, pulse oximetry.

• Targeted values: The use of oxygen (O2) during DR management, the expected SpO2 saturations at 10 min of age and the titration strategy for adapting FiO2 treatment.

• Surfactant therapy: Protocols for Surfactant administration and dosage.

Protocol

The questionnaire was sent by posted mail to all German, Austrian and Swiss children's hospitals with NICU facilities, as identified through the address database of the „Gesellschaft für neonatale und pädiatrische Intensivmedizin" (GNPI = society for neonatal and paediatric intensive care medicine). The questionnaire was sent to the head of the neonatal department of each unit. Four weeks after the initial sending, a reminder questionnaire was sent out to the non-compliant institutions, followed by both Email and telephone contact.

Statistical methods

The reported characteristics are described by incidences and the differences between countries and academic and non-academic institutions were compared by chi-square test or the exact Fischer test, as appropriate. Chi-square was not calculated if total frequency numbers were < 5. For statistical evaluation the software Statgraphics (Vers. 5.0, Manugistics Inc., U.S.A.) was used. A p-level of < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

A total of 190 of the 249 approached neonatal units replied, the mean response rate was 76% (DE: 153/193 (79%), AU: 11/14 (79%), CH: 26/42 (62%). Of the received questionnaires the incidence of missing data due to unanswered items was in the median 3.4% (range 0% to 23.7%). Therefore, in all tables the total number of answers was given. The highest incidence of missing data was regarding the question about presence of a neonatal resuscitation room, the use of flow-inflating bags (FI-bags) and the surfactant treatment.

The characteristics of the responding units are shown in Table 1. Forty-eight units (25%) were academic children's hospitals or teaching hospitals, and 142 (75%) were non-academic units. Almost all units (94%) had written protocols for DR management. There were no statistically significant differences found between the countries' units regarding most items, except for the provision of a 24 hr neonatal in house service and the presence of designated resuscitation area (a special room or cubicle) (p = 0.016 and 0.019, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of the participating institutions (absolute numbers and percent (%) in parenthesis)

| Germany | Austria | Switzerland | All countries | Differences between countries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 153 | N = 11 | N = 26 | N = 190 | p-value | |

| Academic unit | 35/153 (23) | 4/11 (36) | 9/26 (35) | 48/190 (25) | 0.304 |

| Births per year > 1000 | 122/150 (81) | 7/10 (70) | 18/26 (69) | 147/186 (79) | 0.290 |

| > 50 VLBWI neonates per year |

64/152 (42) | 5/11 (45) | 12/26 (46) | 81/189(43) | 0.914 |

| 24 hr in house neonatal service |

148/153 (97) | 11/11 (100) | 21/25 (84) | 180/189 (95) | 0.016 |

| Designated neonatal resuscitation room |

95/117 (81) | 6/9 (67) | 10/19 (53) | 111/145 (77) | 0.019 |

| Neonatal treatment guidelines |

140/149 (94) | 11/11 (91) | 24/26 (92) | 174/186 (94) | 0.889 |

VLBWI = very low birth weight neonate

With regards to the clinical practice of DR management, no statistically significant differences between countries were found regarding the measures for thermal control, circulatory volume and O2-monitoring, as shown in Table 2. However, there were differences between countries with respect to the equipment used for DR management (Table 2). Flow-inflating bags are rarely used in DE (2%) but in more than 20% of AU and CH units (p < 0.001). In contrast, the use of self inflating bags (SI-bags) was common, with 85% for all countries, without statistically significant differences. In particular, they were used in 83% of DE, 89% of au and 96% CH units. SI-bags were often used together with PEEP valves (71% for all countries). less than a quarter of all units used pressure manometers together with SI-bags. Pressure controlled manual resuscitation devices (t-piece resuscitators) were used in 40% of all units, the highest distribution was seen in AU units (80%) compared to 41% (DE) and only 20% in CH units (p = 0.004) (Table 2). No information was obtained on whether the units preferred on device over another.

Table 2.

Clinical practice and equipment used for resuscitation of VLBWI (absolute numbers and percent (%) in parenthesis)

| Germany | Austria | Switzerland | All countries | Differences between countries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 153 | N = 11 | N = 26 | N = 190 | p-value | |

| Circulatory volume- and temperature control | |||||

| Late cord clamping | 62/145 (43) | 5/10 (50) | 11/24(46) | 78/179 (44) | 0.879 |

| Polyethylen foil | 93/151 (62) | 8/10 (80) | 16/26 (62) | 117/187 (63) | 0.504 |

| Head cover | 126/151 (83) | 7/10 (70) | 19/26 (73) | 152/187 (81) | 0.294 |

| Devices for pressure or volume control | |||||

| FI-bag | 2/119 (2) | 2/9 (22) | 6/26 (23) | 10/154 (6) | < 0.001 |

| SI-bag | 113/136 (83) | 8/9 (89) | 25/26 (96) | 146/171 (85) | 0.215 |

| with PEEP valve | 98/136 (72) | 4/9 (44) | 20/26 (77) | 122/171 (71) | 0.164 |

| with manometer | 34/136 (27) | 1/8 (13) | 2/25 (8) | 37/169 (22) | 0.093 |

| Neopuff® | 56/136 (41) | 8/10 (80) | 5/25 (20) | 69/171 (40) | 0.004 |

| Respirator | 66/136 (49) | 2/10 (20) | 4/25 (16) | 72/171 (42) | 0.004 |

| Other pressure control devices | 5/136 (4) | 0/10 (0) | 2/25 (8) | 7/171 (4) | 0.459 |

| Devices with volume control (respirator) | 59/148 (40) | 4/10 (40) | 5/25 (20) | 68/183 (37) | 0.161 |

| Devices without any pressure/volume control | 1/147 (1) | 0/11 (0) | 2/26 (8) | 3/183 (2) | - |

| O2-therapy and monitoring | |||||

| Pulse oximetry | 149/150 (99) | 9/10 (90) | 26/26 (100) | 184/186 (99) | - |

| O2-blenders | 148/152 (97) | 11/11 (100) | 24/25 (96) | 183/188 (97) | 0.248 |

| CO2-detectors | 12/149 (8) | 4/11 (36) | 3/26 (11) | 19/186 (10) | 0.011 |

| Gas heating and humidification | 62/150 (41) | 2/11 (18) | 13/24 (54) | 17/185 (42) | 0.132 |

FI-bag = flow-inflating bag; SI-bag = self-inflating bag; PEEP = positive end expiratory pressure

Table three shows the comparison of the targeted values. The only identified significant difference between the countries was regarding the Surfactant treatment: while DE and CH primarily used 100 ml/kg as a starting dose, the majority of AU units (57%) preferred 150-200 ml/kg (p = 0.002) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Primary target values and parameter settings (absolute numbers and percent (%) in parenthesis)

| Germany | Austria | Switzerland | All countries | Differences between countries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 153 | N = 11 | N = 26 | N = 190 | p-value | |

| Oxygen therapy | |||||

| FiO2 | |||||

| 0.21 | 47/147 (32) | 1/11 (9) | 8/25 (32) | 56/183 (31) | |

| 0.22 - 0.5 | 81/147 (55) | 10/11 (91) | 14/25 (56) | 105/183 (57) | 0.241 |

| 0.51 - 1.0 | 19/147 (13) | 0/11 (0) | 3/25 (12) | 3/183 (12) | |

| Target SpO2 | |||||

| < 85% | 21/145 (14) | 1/7 (14) | 8/24 (33) | 30/176 (17) | |

| 85-90% | 108/145 (74) | 5/7 (71) | 13/24 (54) | 126/176 (72) | 0.231 |

| > 90% | 16/145 (11) | 1/7 (14) | 3/24 (13) | 20/176 (11) | |

| High FiO2, taper down | 31/152 (20) | 2/11 (18) | 2/25 (20) | 38/188 (20) | |

| Low FiO2, taper up | 12/152 (80) | 9/11 (82) | 20/25 (80) | 150/188 (80) | 0.984 |

| Non-invasive respiratory support | |||||

| Prolonged inflations | 41/148 (28) | 3/11 (27) | 3/25 (12) | 47/184 (26) | 0.248 |

| > 5 sec | |||||

| Starting CPAP | |||||

| ≤ 3 cmH20 | 9/149 (6) | 0/0 (0) | 1/21 (5) | 10/180 (6) | |

| 4-5 cmH20 | 114/149 (77) | 6/10 (60) | 19/21 (90) | 139/180 (77) | 0.170 |

| > 5 cmH20 | 26/149 (17) | 4/10 (40) | 1/21 (5) | 31/180 (17) | |

| Invasive respiratory support | |||||

| INSURE yes | 43/142 (30) | 4/9 (44) | 4/19 (21) | 51/170 (30) | 0.444 |

| Surfactant | |||||

| 100 mg/kg | 129/145 (89) | 3/7 (43) | 11/14 (79) | 143/166 (86) | 0.002 |

| 150-200 mg/kg | 16/145 (11) | 4/7 (57) | 3/14 (21) | 23/166 (14) | |

FiO2 = fraction of inspired oxygen

CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure

INSURE = intubate, surfactant application, extubate immediately

SpO2 = peripheral saturation of oxygen

Only minor differences between academic and nonacademic units were found (Table 4 and 5). While head covers were significantly less often used (p < 0.001) in academic units, SI-bags were more often used here (p = 0.006), and devices for volume control were used less frequently in academic units (p = 0.042). Regarding the comparison of targeted values, protocols of academic and non-academic of units were widely comparable, except in a weak, however statistically significant difference for the targeted values for SpO2 (p = 0.023) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Comparison by level of care (academic vs. non-academic clinic) in clinical practice and equipment used for resuscitation of VLBWI (absolute numbers and percent (%) in parenthesis)

| Academic Hospital | Non-Academic Hospital | Differences between institutions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 48 | N = 142 | p-value | |

| Circulatory volume- and temperature control | |||

| Late cord clamping | 25/48 (52) | 53/131 (41) | 0.165 |

| Polyethylen foil | 30/48 (63) | 87/139 (63) | 0.991 |

| Head cover | 31/48 (65) | 121/139 (87) | < 0.001 |

| Devices for pressure or volume control | |||

| FI-bag | 2/41 (5) | 8/113 (7) | 0.624 |

| SI-bag | 44/45 (98) | 102/126 (81) | 0.006 |

| with PEEP valve | 32/44 (73) | 90/127 (71) | 0.814 |

| with manometer | 6/43 (14) | 31/116 (27) | 0.091 |

| Neopuff® | 21/44 (48) | 48/127 (38) | 0.247 |

| Respirator | 15/44 (34) | 57/127 (45) | 0.212 |

| Other pressure control devices | 1/47 (2) | 2/136 (1) | 1.000 |

| Devices without any pressure control | 1/40 (3) | 2/112 (2) | 0.875 |

| Devices with volume control (respirator) | 12/48 (25) | 46/135 (42) | 0.042 |

| O2-therapy and monitoring | |||

| Pulse oximetry | 48/48 (100) | 136/138 (99) | 1.000 |

| O2-blenders | 45/48 (94) | 138/140 (99) | 0.106 |

| CO2-detectors | 5/48 (10) | 14/138 (10) | 0.957 |

| Gas heating and humidification | 16/48 (33) | 61/137 (45) | 0.176 |

FI-bag = flow-inflating bag

Neopuff® = most commonly used T-piece resuscitator

SI-bag = self-inflating bag

PEEP = positive end expiratory pressure

Table 5.

Comparison by level of care (academic vs. non-academic clinic) in primary target values and parameter settings (absolute numbers and percent (%) in parenthesis)

| Academic Hospital | Non-Academic Hospital | Differences between institutions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 48 | N = 142 | p-value | |

| Oxygen therapy | |||

| FiO2 | |||

| 0.21 | 15/45 (33) | 41/138 (30) | |

| 0.22 - 0.5 | 26/45 (58) | 79/138 (57) | 0.728 |

| 0.51 - 1.0 | 4/45 (9) | 18/138 (13) | |

| Target SpO2 | |||

| < 85% | 12/47 (26) | 18/129 (14) | |

| 85-90% | 34/47 (72) | 92/129 (71) | 0.023 |

| > 90% | 1/47 (2) | 19/129 (15) | |

| High FiO2, taper down | 7/48 (15) | 31/140 (22) | |

| Low FiO2, taper up | 41/48 (85) | 109/110 (78) | 0.260 |

| Non-invasive respiratory support | |||

| Prolonged inflations > 5 sec | 11/46 (24) | 36/138 (26) | 0.770 |

| Starting CPAP | |||

| ≤ 3 cmH20 | 3/45 (7) | 7/135 (5) | |

| 4-5 cmH20 | 31/45 (69) | 108/135 (80) | 0.288 |

| > 5 cmH20 | 11/45 (24) | 20/135 (15) | |

| Invasive respiratory support | |||

| INSURE yes | 12/47 (26) | 39/123 (32) | 0.432 |

| Surfactant | |||

| 100 mg/kg | 30/39 (77) | 113/127 (89) | 0.109 |

| 150-200 mg/kg | 9/39 (13) | 14/127 (11) | |

CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure

FiO2 = fraction of inspired oxygen

SpO2 = peripheral saturation of oxygen

INSURE = intubate, surfactant application, extubate immediately

Comparison of the DR management of VLBWI from our studied units showed good accordance to the latest ILCOR guidelines 2005, with the exception to the use of CO2-detectors (Table 2). However, we also have observed the widely used incorporation of very recent, high quality evidence as for instance delayed cord clamping [17], gas conditioning or oxygen therapy, irrespective of the lack of a clear statement in the ILCOR 2005 publication [1] (Table 2).

Discussion

The results from 190 neonatal units from Germany, Austria and Switzerland showed that DR management in these countries was performed at a similar standard and in good accordance with the 2005 ILCOR guide lines. Guidelines for DR management existed in almost all units. Only minor differences were found between countries regarding the provision of a 24 hr neonatal service and presence of a designated resuscitation area, the means for thermal support, the equipment used for giving ventilatory support and regarding the targeted values, or the initial dosage of Surfactant. Apart from the use of head covers and use of devices for volume control (most prevalent in non-academic units) and SI-bags (more prevalent in academic teaching units), as well as different target levels for SpO2 at 10 min. of life, there were no statistically significant differences between academic and non-academic units.

The clinical practice of DR management, as reflected in our survey of protocols of German, Austrian and Swiss neonatal units is discussed below. The protocols were related to the recommendations given by ILCOR in 2005 [1]. With regards to measures for thermal control, significant differences were found between the protocols in German speaking countries and the 2005 ILCOR recommendations: only 63% of responding units used polyethylen wrappings but 81% used head covers. Taking into account that these procedures require only inexpensive equipment and little time, and despite good evidence and clear ILCOR recommendations towards their use, it is not clear why these measures were not universally employed [1,23,30]. However conversely, although no clear-cut recommendations on late cord clamping were given for preterm neonates in the 2005 ILCOR guidelines, according to our survey 44% of units already advise to perform late cord clamping (> 30 sec), much in line with evidence from a recent meta-analysis [15].

Regarding the use of devices for non-invasive manual ventilatory support, ILCOR 2005 is open towards the use of SI- bags, FI-bags or T-piece resuscitation devices. All devices were considered useful, without specification [1]. However, recent experimental evidence stresses the preference of pressure-controlled devices over SI-bags for giving manual ventilatory support to VLBWIs [2,18]. From the results of our survey, we can see that T-piece, pressure controlled ventilation devices are becoming well established for use in the DR (40%). Use of a pressure manometer together with an SI-bag was current practice in 22% of units. Regarding ventilation strategies during resuscitation, it is mentioned in the ILCOR guidelines that there was insufficient data to support or refute the routine use of CPAP/PEEP during or immediately after resuscitation in the delivery room [1]. However, although not specified in the 2005 ILCOR guidelines, use of PEEP was commonly employed, the median starting CPAP/PEEP pressure was 5 cmH2O. This value has already been recognized as the median starting CPAP level for most German NICUs [19]. Another interesting observation is the discrepancy between the guidelines and common practice as exemplified by the administration of sustained inflations: while mentioned in ILCOR, but not formally suggested in 2005 [1], as many as 26% of units from the German speaking countries do administer sustained inflations < 5 sec. during DR management of VLBWI. It can be assumed that those units act on the basis of evidence from two small trials, illustrating some positive effects of sustained inflations [11,25]. A further deviation from ILCOR 2005 was found regarding the use of CO2 detectors. Such kits can be used for confirming endo-tracheal tube placement and are being recommended for this purpose in the 2005 ILCOR statement [1]. Strikingly, while qualitative and quantitative CO2 detectors were already described to be used by 32% of North American NICUs in Leone's paper in 2006, two years later, only 10% of the NICUs from our survey claimed to use these to confirm tracheal tube placement [10]. The reasons for this remain speculative and may warrant further investigation [5]. With respect to gas conditioning, although not specified in the ILCOR guidelines, and as so far only experimental data is available [14], as many as 42% of units claim to already use heated and humidified gas in the DR. Despite these fine differences to the recommendations by ILCOR 2005, common practice of DR airway management within the German speaking countries is widely in line with the most recently reviewed advances in care of the newly born preterm lung [21,22].

The particular issue of oxygen administration and peripheral monitoring of oxygenation and the shortcomings of the ILCOR guidelines were already discussed in detail by other colleagues [8,6]. In short, while the ILCOR guideline says the supplementation of oxygen should be considered „if central cyanosis was persistent during resuscitation and hyperoxia should be avoided" [1]. Several recent meta-analyses have helped to educate us on a more judicious use of O2 in the context of delivery room management [24,16,20]. The discrepancy between guidelines and most recent evidence on the use of O2 was addressed in a recent publication, aimed for the German readership [6]. According to our survey, only 31% of the units quoted a starting FiO2 of 0.21, while 57% would use a FiO2 of 0.22-0.55 and just 12% would use a FiO2 of 1.0. Also, around 80% of the surveyed units preferred to start with a low FiO2 and then increase FiO2 if necessary (step up), 20% would use a step down approach. The ILCOR and ERC guidelines also recommend the use of an incremental approach [1].

A comparison of our results to data on DR management in other European countries yields interesting results. Differences were observed in particular with respect to the airway management and control of oxygen delivery [8,27]. When compared to Spanish and Italian data, it becomes obvious that the German speaking countries act consistently on the basis of a written protocol. This was very recently confirmed by the study of Schmölzer et al. [22]. It is not known from the literature whether written protocols were used in other European countries. However, according to Iriondo and co-workers, every neonatal team in Spain employs a neonatologist trained under the national neonatal training scheme, hence a common national DR procedure can be expected [8]. We believe the observed institutional and national differences are very interesting with regards to the question how best evidence is distributed and how it can be most effectively be incorporated in to local guidelines. Data from other European countries should also be obtained in order to survey the local practice guidelines; a copy of our questionnaire is available found in the appendix of this paper.

Further, means to distribute the best available evidence on neonatal resuscitation in order to incorporate it in to common practice should be investigated. Spain, where a common national training programme for neonatologists exists and its completion is compulsory before physicians take over responsibilities in the NICU, may act as a leading example. Other means to keep up to date would be by the use of the internet, with the installation of an evidence-based website with particular focus on neonatal resuscitation. Such a project is currently under construction http://www.neonatologie.org.

In conclusion, DR management is based on written protocols and is being operated almost similarly throughout German, Austrian and Swiss neonatal units, and in academic and non-academic units. We found only minor differences regarding the DR setup and equipment used, as well as for targeted values of SpO2 and FiO2. Protocols were in good accordance with the recent 2005 ILCOR guidelines. Where available, emerging high quality evidence that was not in the 2005 ILCOR statement has been adopted into local protocols of many units.

Abbreviations

AU: Austria; BW: birth weight; CO2: carbon dioxide; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; CH: Switzerland; DE: Germany; DR: delivery room; ERC: European Resuscitation Council; FI-bag: flow-inflating bag; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; GA: gestational age; ILCOR: International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation; NICU: neonatal intensive care unit; n.s.: not statistically significant; O2: oxygen; RR: respiratory rate; SI-bag: self-inflating bag; SpO2: peripheral oxygen saturation; VLBWI: very low birth weight infant (birth weight less than 1500 g).

Conflicting interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix

Participating units

Germany

• Abt. Allgemeinpädiatrie der Kinderklinik St. Annastift Ludwigshafen

• Abt. für Kinderheilkunde der St.-Antonius-Hospital gGmbH

• Abteilung für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Ev. Waldkrankenhaus Berlin Spandau

• Abteilung für Kinderheilkunde des Marienhospital Wesel

• Abteilung für Neonatologie der Asklepios Klinik Barmbek, Hamburg

• Abteilung für Neonatologie des Ludmillenstiftes Meppen

• Abteilung für Neonatologie des Universitätsklinikum Bonn

• Abteilung für Neonatologie, DRK Klinikum Berlin Westend

• Allg. Pädiatrie des Universitätsklinikums Schleswig-Holstein, Kiel

• Dipl.-Med. R. Hanusch, Kinderklinik des Klinikums Obergöltzsch Rodewisch

• Dr. A. Hennenberger, Neonat. päd. Intensivmedizin des Kinderkrankenhauses Wilhelmstift, Hamburg

• Dr. med. A. Zimmermann, Kinderklinik und Poliklinik des Klinikum rechts der Isar, München

• Dr. med. Axel von der Wense, Altonaer Kinderkrankenhaus Hamburg

• Dr. med. B. Knittel, Kinderklinik 1 des Städt. Klinikums Magdeburg

• Dr. med. B. Mackowiak, Neonatologische Intensivmedizin am Ev. Krankenhaus Hamm

• Dr. med. B. Schmidt, Zentrum Josephinchen für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des St. Joseph-Krankenhauses Berlin

• Dr. med. C. Andrée, Zentrum für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des HELIOS Klinikum Krefeld

• Dr. med. C. Aring, Kinderklinik St. Nikolaus des Allg. Krankenhauses Viersen GmbH

• Dr. med. D. Richter, Abteilung für Kinderheilkunde der Klinik am Eichert, Göppingen

• Dr. med. F. Niemann, Abteilung für Intensivmedizin, Neonatologie der Bergmannshell und Kinderklinik Buer gGmbH Gelsenkirchen

• Dr. med. F. Stemberg, Kinderklinik, Neonatologie des Klinikums Worms

• Dr. med. F. Wild, Kinderklinik St. Elisabeth, Neuburg/Donau

• Dr. med. G. Frey, Südhessisches Perinatalzentrum/Neonatologie Darmstadt

• Dr. med. G. Hammersen, Cnopf'sche Kinderklinik Nürnberg

• Dr. med. G. Selzer, Dr. med. P. Lasch, Klinik f. Neonatologie u. päd. Intensivmedizin der Klinikum Bremer-Mitte gGmbH, Bremen

• Dr. med. H. Broede, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Klinikums Detmold

• Dr. med. H. Krull, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin der Krankenhaus am Rosarium GmbH (jetzt HELIOS Klinik Sangerhausen), Sangerhausen

• Dr. med. H. Voss, Kinderklinik des Klinikums der Landeshauptstadt Wiesbaden - Dr.-Horst-Schmidt-Kliniken

• Dr. med. H.-G. Hoffmann, Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Mathias-Spital Rheine

• Dr. med. H.-J. Bittrich, Neonatologie/Kinder IST des HELIOS Klinikums Erfurt

• Dr. med. H.-U. Peltner, Klinik für Kinderheilkunde und Jugendmedizin des St. Bernward Krankenhauses Hildesheim

• Dr. med. H.T. Körner, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin - Intensivstation des Klinikums Links der Weser gGmbH

• Dr. med. I. Hörning-Franz, Neonatologie und päd. Intensivmedizin des Uniklinikums Münster

• Dr. med. I. Müller-Hansen, Abt. Neonatologie der Uniklinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin Tübingen

• Dr. med. J. Herrmann, Klinik für Kinder und Jugendliche des Leopoldina-Krankenhauses Schweinfurt

• Dr. med. J. Nawracala, Abt. für Neonatologie des Kinderhospitals Osnabrück

• Dr. med. K. Niethammer, Klinik für Kinder und Jugendliche des Klinikums Esslingen

• Dr. med. K.-U. Schunck, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Vivantes Klinikum Berlin Friedrichshain

• Dr. med. M. Vochem, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Olgahospital Stuttgart

• Dr. med. O. Kannt, Klinik für Neonatologie und Neuropädiatrie des HELIOS Klinikums Schwerin

• Dr. med. P. Dahlem, Pädiatrische Intensivmedizin der Klinikum Coburg gGmbH, Coburg

• Dr. med. P. Jesche, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin der Klinikum Hoyerswerda gGmbH

• Dr. med. R. Muchow, Kinder- u. Jugendklinik des Klinikums Herford

• Dr. med. R. Vortkamp, Kinderklinik & Perinatalzentrum der Westpfalz-Klinikum GmbH Kaiserslautern

• Dr. med. S. Thönnißen, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des St. Bonifatius Hospitals Lingen (Ems)

• Dr. med. Saur, Kinderklinik des Ostalb-Klinikums Aalen

• Dr. med. St. Seeliger, Klinik für Kinderheilkunde u. Jugendmedizin des Universitätsklinikums Göttingen

• Dr. med. T. Hofmann, Abt. für Kinderheilkunde des Klinikums Lippstadt

• Dr. med. T. Hoppen, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Gemeinschafts-Klinikums Koblenz-Mayen, Koblenz

• Dr. med. U. Spille, Neonatologische und päd. Intensivstation des Klinikums Herford

• Dr. med. V. Arpe, Abt. für Neonatologie der St. Marien-Hospital gGmbH Düren

• Dr. med. V. Boldis, Klinik für Kinder und Jugendliche der ASKLEPIOS Klinikum Uckermark GmbH, Schwedt/Oder

• Dr. med. W. Garbe, Perinatalzentrum/Neonatologie des St.-Marien-Hospitals Bonn

• Dr. med. W. Lehnen, Kinderklinik des St. Clemens Hospitale Sterkrade gGmbH Oberhausen

• Dr. med. W. Müller, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Krankenhauses Neuwerk, Mönchengladbach

• DRK-Kinderklinik Siegen

• Josefinum Kinderkrankenhaus Augsburg

• Kinder - und Jugendmedizin der GPR Klinikum Rüsselsheim gGmbH

• Kinder- und Jugendklinik des Universitätsklinikums Erlangen

• Kinderabteilung der Filderklinik Filderstadt-Bonlenden

• Kinderabteilung des Diakonie-Krankenhauses Bad Kreuznach

• Kinderabteilung des Kreiskrankenhauses Traunstein

• Kinderabteilung Heidekreisklinikum GmbH Soltau

• Kinderintensivstation des Elbe Klinikums Stade

• Kinderklinik der Allgemeines Krankenhaus gGmbH Hagen

• Kinderklinik der SLK-Kliniken Heilbronn GmbH, Heilbronn

• Kinderklinik der Städt. Kliniken Frankfurt a. M. - Höchst

• Kinderklinik des Diak. Werks Kaiserswerth, Krankenanstalten "Florence Nightingale", Düsseldorf

• Kinderklinik des Klinikums Aschaffenburg

• Kinderklinik des Klinikums Bamberg

• Kinderklinik des Klinikums Hildesheim GmbH

• Kinderklinik des Klinikums Kassel

• Kinderklinik des Klinikums Rosenheim

• Kinderklinik des Kreiskrankenhauses Waiblingen

• Kinderklinik des Städt. Klinikums Brandenburg a.d. Havel

• Kinderklinik des Werner-Forßmann-Krankenhauses Eberswalde

• Kinderklinik des Zentralklinikums Suhl

• Kinderklinik Dritter Orden, Passau

• Kinderklinik u. Poliklinik des Universitätsklinikums Essen

• Kinderklinik und Poliklinik des Städtischen Krankenhauses München Schwabing

• Kinderkrankenhaus St. Marien des Krankenhaus Landshut

• Klinik für Kinder und Jugendliche der Klinikum Idar-Oberstein GmbH, Idar-Oberstein

• Klinik für Kinder und Jugendliche der Städt. Kliniken Oldenburg gGmbH, Oldenburg

• Klinik für Kinder und Jugendmedizin Bad Hersfeld

• Klinik für Kinder- u. Jugendmedizin des Elisabeth-Krankenhauses Reydt Mönchengladbach

• Klinik für Kinder- u. Jugendmedizin des Ev. Krankenhauses Bielefeld

• Klinik für Kinder- u. Jugendmedizin des Klinikums Ludwigsburg

• Klinik für Kinder- u. Jugendmedizin des St.-Agnes-Hospitals Bocholt

• Klinik für Kinder- u. Jugendmedizin des Städt. Krankenhauses Kiel

• Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin der Johanniter-Krankenhaus Genthin-Stendal gGmbH

• Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin der Klinikum Hanau gGmbH, Hanau

• Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin der Uniklinik des Saarlandes Homburg/Saar

• Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Ernst von Bergmann Klinikums Potsdam

• Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des HELIOS Vogtland-Klinikums Plauen

• Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Klinikum Fulda

• Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Krankenhaus Freudenstadt

• Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Sana Klinikums Berlin Lichtenberg

• Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des St. Georg Klinikums Eisenach gGmbH

• Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des St. Elisabeth und St. Barbara- Krankenhauses Halle

• Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Städt. Klinikums Karlsruhe gGbmH

• Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Vivantes Klinikums Berlin Neukölln

• Klinik für Neonatologie der Charité, Campus Virchow Klinikum Berlin

• Klinik und Poliklinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Universitätsklinikums Münster

• Neonatologie/Pädiatrische Intensivmedizin des Städt. Krankenhauses Harlaching, München

• Neonatologische Intensivmedizin, Klinikum der RWTH Aachen

• Neonatologische und interdisziplinäre pädiatrische Intensivmedizin der Kliniken der Stadt Köln gGmbh

• OA Dipl.-Med. H.U. Thomalla, Kinderklinik & Ambulanz des Städt. Klinikums Dessau

• OA Dr. med. A. Höck, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des HELIOS Klinikum Berlin Buch

• OA Dr. med. A. Sandvoss, Kinderklinik des Städtischen Klinikums Braunschweig

• OÄ Dr. med. B. Linse, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin der Klinikum St. Georg gGmbH

• OA Dr. med. C. Bender, Abt. Neonatologie des Klinikums der Stadt Villingen-Schwenningen GmbH

• OA Dr. med. C. Hünseler, Perinatalzentrum der Uniklinik Köln

• OA Dr. med. C. Willaschek Kinderklinik des Caritaskrankenhauses Bad Mergentheim

• OA Dr. med. D. Kamprad, Klinik für Kinderheilkunde der Klinikum Chemnitz gGmbH

• OA Dr. med. D. Wetzel, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin der Thüringen-Klinik

• OÄ Dr. med. Katrin Manzke, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Dietrich-Bonhoeffer-Klinikums Neubrandenburg

• OA Dr. med. M. Welsch, Abt. für Neonatologie des Klinikums Deggendorf

• OA Dr. med. S. Avenarius, Neonatologie/Päd. Intensivmedizin der Universitätskinderklinik Magdeburg

• OA Dr. med. V. Kunde, neonatologische und pädiatrische Intensivstation der Marienhospital Osnabrück GmbH, Osnabrück

• OA Dr. med. W.E. Boehm et al., Neonatologie und päd. Intensivmedizin der DRK-Kinderklinik Siegen gGmbH, Siegen

• OA Dr. R. Haase und OÄ Dr. med. U. Lieser, Neonatologie u. päd. Intensivmedizin des Universitätsklinikums Halle (Saale)

• Päd. Intensivmedizin u. Neonatologie, Perinatalzentrum des HELIOS Klinikums Wuppertal

• Pädiatrische Abteilung des St. Elisabeth Krankenhauses Neuwied

• PD Dr. med. A. Hübler, Neonatologie und Pädiatrische Intensivmedizin des Universitätsklinikums Jena

• PD Dr. med. B. Bohnhorst, Päd. Pneumologie und Neonatologie der Medizinischen Hochschule Hannover

• PD Dr. med. B. Erdlenbruch, Klinik für Kinder und Jugendmedizin des Johannes Wesling Klinikums Minden

• PD Dr. med. C. Roll, Kinder- u. Jugendklinik der Universität Witten/Herdecke, Datteln

• PD Dr. med. J. Dembinski, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin der Ruppiner Kliniken GmbH Neuruppin

• PD Dr. med. R. Hentschel, Zentrum f. Kinderheilkunde und Jugendmedizin des Klinikums Freiburg

• PD Dr. med. Th. Erler, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin des Carl-Thiem-Klinikums Cottbus

• Perinatalzentrum Neonatologie an der Frauenklinik der Ludwig-Maximilian-Universität, München

• Prof. Dr. G. Buheitel, Klinik für Kinder und Jugendliche des Klinikums Augsburg

• Prof. Dr. med. Dipl. Chem. J. Pöschl, Abteilung Neonatologie der Universitätsklinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Heidelberg

• Prof. Dr. med. E. Kattner, Kinderkrankenhaus auf der Bult, Hannover

• Prof. Dr. med. H. Hummler, Universitätsklinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin Ulm

• Prof. Dr. med. H. Segerer, Abt. für Neonatologie der Klinik St. Hedwig, Krankenhaus Barmherzige Brüder Regensburg

• Prof. Dr. med. M. Rüdiger, Abt. für Neonatologie u. Intensivmedizin des Universitätsklinikums "Carl Gustav Carus", Dresden

• Prof. Dr. med. P. Haas, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin der Ernst-Moritz-Arndt Universität Greifswald

• Prof. Dr. med. R. Galaske, Klinik für Kinder und Jugendliche der SHG Kliniken Merzig

• Prof. Dr. med. U. Thome, Universitätsklinik und Poliklinik für Kinder- und Jugendliche Leipzig

• Prof. Dr. W. Nikischin, Neugeborenen-Intensivstation des Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein

• Sektion Neonatologie und Pädiatrische Intensivmedizin des Universitätsklinikums Hamburg-Eppendorf

• Universitäts-Kinderklinik Würzburg

• Zentrum der Kinderheilkunde des Universitätsklinikums Frankfurt/Main

Switzerland

• Dr. P. Diebold, Médecin-Chef, Hopital du Chablais, Aigle

• Dr. M. Wopmann, Kantonsspital Baden

• Prof. Dr. Chr. Bührer, Universitäts-Kinderspital beider Basel, Neonatologie, Basel

• Dr. R. Glanzmann, UKBB Basel/Bruderholz

• PD Dr. M. Nelle, Neonatologie, Med. Univ.-Kinderklinik, Inselspital, Bern

• Dr. Ph. Curchod, Hospitaliers du Nord Vaudois, Yverdon-les-Bains, Champlon

• Dr. Brigitte Scharner, Kantonsspital Graubünden, Dep. F. Kinder- u. Jugendmedizin, Chur

• Dr. Anita Truttmann, Médecin associè PD MER CHUV, Division de Néonatologie, Lausanne

• Dr. D. Dell' Allolino, Oberarzt Pädiatrie, Luzern

• PD Dr. Th. Berger, Kinderspital Luzern, NeoIPS, Luzern

• Dr. Zemmouri, Hopital de Morges, pediatrie Morges

• PD Dr. B. Laubscher, Hopital Pourtalès, Pèdiatre FMH, Neuchatel

• Dr. E. Pythoud, Médecin-chef du Service Hopital intercantonal de la Broye, Payerne

• Prof. Dr. Bianchetti, OBV Mendrisio Pediatria + Ginec, Mendrisio Kinderspital St. Gallen

• Dr. M.-A. Panchard, L'Hopital Riviera, Service du pédiatrie, Vevey

• Dr. Roten, Praxis Spitalzentrum Oberwallis, Viége

• Dr. U. Zimmermann, Kinder- u. Jugendmedizin, Neonatologie, Winterthur

• PD Dr. J.-C. Fauchère, Klinik für Neonatologie, Univ.-Spital Zürich

Austria

• Prim. Dr. B. Ausserer, Krankenhaus Dornbirn, Kinder- und Jugendheilkunde, Dornbirn

• Univ.Prof. Dr. G. Simbruner, Univ.-Klinik für Kinder- u. Jugendmedizin, Innsbruck

• Prim. Dr. Claudia Haberland, Bezirkskrankenhaus Kufstein, Kinder- u. Jugendheilkunde, Kufstein

• Dr. M. Weissensteiner, Landes-Frauen- und Kinderklinik Linz, Linz

• Prim. Dr. W. Müller, A.ö. Bezirkskrankenhaus, Kinder- u. Jugendstation, Reutte

• Prim. Dr. J. Rücker, Salzburger Landeskliniken, Neonatologie, ITS, Salzburg

• Univ.-Kinder- und Jugendheilkunde, Neonatologie, Magistrat der Stadt Wien, Allgem. Krankenhaus, Wien

• Prim. Dr. K. Gutenberger, Krankenhaus St. Vinzenz, Kinder- u. Jugendheilkunde, Zams

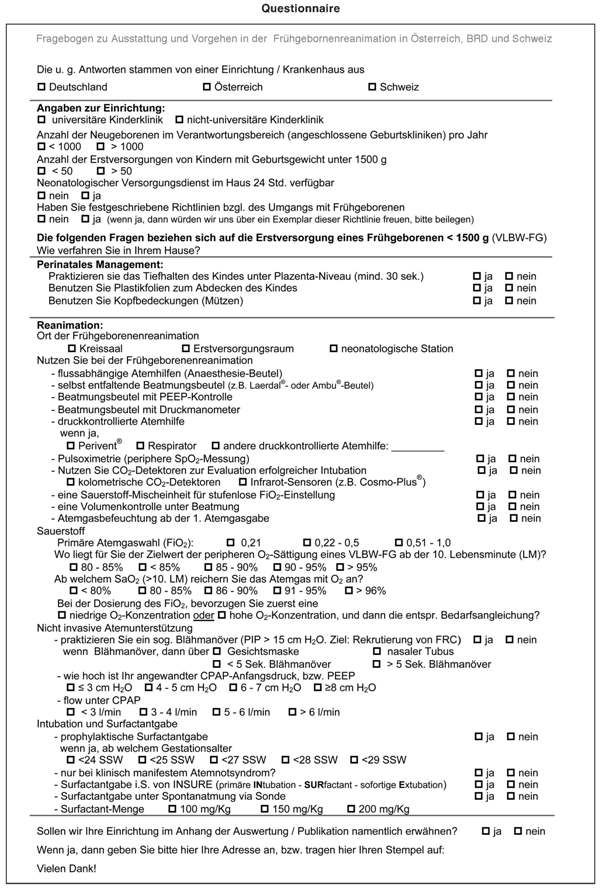

Questionnaire

Figure 1.

Questionnaire

Acknowledgements

• Special thanks to the participating representatives of the surveyed clinics in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. A detailed account of the participating institutions can be found in the appendix.

• Parts of the results were presented by Dr. C. C. Roehr as oral presentations at the annual meetings of the GNPI in 2009 and 2010, and at the UK Neonatal Society annual meeting 2009.

• We thank our data management assistants Jessica Blank and Elena Roell for helping with the data acquisition and data management. Thanks to Dr Peter Waugh for the language editing.

References

- American Heart Association, American Academy of Pediatrics. 2005 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiovascular care (ECC) of pediatric and neonatal patients: neonatal resuscitation guidelines. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e978–e988. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S, Finer NN, Rich W. A comparison of three neo natal resuscitation devices. Resuscitation. 2005;67:113–8. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2005. Section 6. Paediatric life support. Resuscitation. 2005;67S1:S97–S133. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanaroff AA, Stoll BJ, Wright LL, Carlo W, Ehrenkrantz RA, Stark AR, Bauer CR, Korones SB, Lap-took RA, Lemmons JA, Oh W, Papile LA, Shankaran S, Stevensons DK, Tyson JE, Poole WK. NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Trends in neonatal morbidity and mortality for very low birth weight infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:147.e1–147.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey DM, Ward R, Rich W, Heldt G, Leone T, Finer NN. Tidal volume threshold for colorimetric carbon dioxide detectors available for use in neonates. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1524–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann G, Humpl T, Zimmermann A, Bührer C, Wauer R, Stannigel H, Hoehn T. [ILCOR's new resuscitation guidelines in preterm and term infants: critical discussion and suggestions for implementation] Klin Padiatr. 2007;219:50–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-970072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. 2005 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation. 2005;112:III-1–III-136. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iriondo M, Thió M, Burón E, Salguero E, Aguayo J, Vento M. the Neonatal Resuscitation Group (NRG) of the Spanish Neonatal Society (SEN) A survey of neonatal resuscitation in Spain: gaps between guidelines and practice. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:786–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe AH, Hillman N, Polglase G, Kramer BW, Kallapur S, Pillow J. Injury and inflammation from resuscitation of the preterm infant. Neonatology. 2008;94:190–6. doi: 10.1159/000143721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone T, Rich W, Finer N. A Survey of delivery room resuscitation practices in the United States. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e164–e175. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner W, Högel J, Pohlandt F. Sustained pressure-controlled inflation or intermittent mandatory ventilation in preterm infants in the delivery room? A randomized, controlled trial on initial respiratory support via nasopharyngeal tube. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:303–9. doi: 10.1080/08035250410023647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser T. Teamwork and patient safety in dynamic domains of healthcare: a review of the literature. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:143–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell CJ, Stewart M, Mildenhall M. Neonatal resuscitation in Australia and New Zealand. J Paed Child Heath. 2006;42:4–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillow JJ, Hillman NH, Polglase GR, Moss TJ, Kallapur SG, Cheah FC, Kramer BW, Jobe AH. Oxygen, temperature and humidity of inspired gases and their influences on airway and lung tissue in near-term lambs. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:2157–63. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1624-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe H, Reynolds G, Diaz-Rossello J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of a brief delay in clamping the umbilical cord of preterm infants. Neonatology. 2008;93:138–44. doi: 10.1159/000108764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabi Y, Rabi D, Yee W. Room air resuscitation of the depressed newborn: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2007;72:353–63. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.06.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajani A, Chitkara R, Halamek L. Delivery room management of the newborn. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:515–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehr CC, Kelm M, Fischer HS, Bührer C, Schmalisch G, Proquitté H. Manual ventilation devices in neonatal resuscitation: tidal volume and positive pressure-provision. Resuscitation. 2010;81:202–5. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehr CC, Schmalisch G, Khakban A, Proquitté H, Wauer RR. Use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in neonatal units - a survey of current preferences and practice in Germany. Eur J Med Res. 2007;12:139–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saugstad OD, Ramji S, Soll RF, Vento M. Resuscitation of newborn infants with 21% or 100% oxygen: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Neonatology. 2008;94:176–82. doi: 10.1159/000143397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmölzer G, Olischar M, Raith W, Resch M, Reiterer F, Müller W, Urlesberger B. Erstversorgung von Neugeborenen. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2010;158:471–476. doi: 10.1007/s00112-010-2171-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmölzer GM, Te Pas AB, Davis PG, Morley CJ. Reducing lung injury during neonatal resuscitation of preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2008;153:741–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soll RF. Heat loss prevention in neonates. J Perinatol. 2008;28(suppl 1):s57–9. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan A, Schulze A, O'Donnell CP, Davis PG. Air versus oxygen for resuscitation of infants at birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;18:CD002273. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002273.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- tePas AB, Walther FJ. A randomized, controlled trial of delivery-room respiratory management in very preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2007;120:322–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EJ, Sexton JB, Lasky RE, Helmreich RL, Crandell DS, Tyson J. Teamwork and quality during neonatal care in the delivery room. J Perinatol. 2006;26:163–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevisanuto D, Doglioni N, Ferrarese P, Bortolus R, Zanardo V. Neonatal Resuscitation Study Group, Italian Society of Neonatology. Neonatal resuscitation of extremely low birthweight infants: a survey of practice in Italy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91:F123–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.079772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vento M, Aguar M, Leone TA, Finer NN, Gimeno A, Rich W, Saenz P, Escrig R, Brugada M. Using intensive care technology in the delivery room: a new concept for the resuscitation of extremely preterm neonates. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1113–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vento M, Cheung PY, Aguar M. The first golden minutes of the extremely-low-gestational-age neonate: a gentle approach. Neonatology. 2009;95:286–298. doi: 10.1159/000178770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohra S, Roberts RS, Zhang B, Janes M, Schmidt B. Heat Loss Prevention (HeLP) in the delivery room: a randomized controlled trial of polyethylene occlusive skin wrapping in very preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2004;145:750–753. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.07.036. Received: September 1, 2010/Accepted: October 26, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]