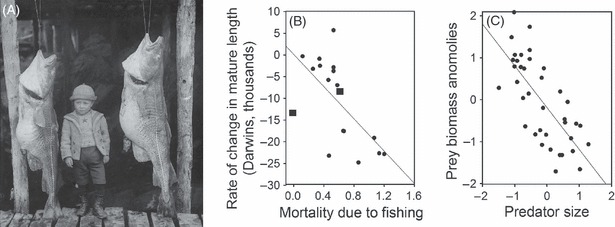

Figure 3.

Effects of fisheries-induced trait change on the Western North Atlantic ecosystem. (A) The photograph Big cod fish from the trap, Battle Harbour, Labrador/Robert Edwards Holloway [1901] shows the size of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) harvested off Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, at the turn of the last century. The plate noted: ‘The larger fish measured 5 ft. 5 in., and weighed 60 lbs’. (B) Intense mortality owing to fishing has driven rapid declines in mature fish length for 18 commercially exploited fish stocks (panel modified from Sharpe and Hendry 2009). Cod stocks in the Western North Atlantic are highlighted as squares in this panel. Note that the rate of decrease in size and the intensity of fishing pressure for cod are average for the stocks included in this study, suggesting that the dramatic and well-publicized declines seen in cod are typical (not exceptional) for intensively harvested fish stocks. (C) Decreases in the body size of cod and other top predators on the Western Scotian Shelf have resulted in a 300% increase in the biomass of prey species (zooplankton, small planktivorous, and detritivorous fishes), despite no change in total predator biomass (panel modified from Shackell et al. 2010). The analysis of Shackell et al. (2010) found anomalies from the mean prey biomass over 38 years of surveys were strongly and negatively related to a standardized index of top predator size. Taken together, these data provide evidence that harvest-induced changes in predator body size can cause trophic cascades that can impact the functioning of entire marine ecosystems.