Abstract

The keyhole technique, which involves the acquisition of dynamic data at low resolution in combination with a high-resolution reference, is developed for the purposes of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging, i.e. Keyhole CEST. Low-resolution data are acquired with saturation applied at different frequencies for Z-spectra, along with a high-resolution reference image taken without saturation. Three methods for high-resolution reconstruction of Keyhole CEST are evaluated using the values from quantitative high-resolution CEST maps. In addition, Keyhole CEST is applied for collection of data used for B0 correction. The Keyhole approach is evaluated for CEST contrast generation using exchanging protons in hydroxyl groups. First, the techniques are evaluated in vitro using samples of dextrose and chondroitin sulfate. Next, the work is extended in vivo to explore its applicability for gagCEST. Comparable quantitative gagCEST values are found using Keyhole CEST, provided the structure or region of interest is not limited by the low-resolution dataset.

Keywords: keyhole, CEST, WASSR, gagCEST, generalized series

Introduction

The keyhole technique in MRI was developed for the under sampling of data collected in a dynamic series and has been applied to dynamic contrast enhanced studies [1]. Keyhole MRI allows for a reduction in the acquisition matrix by concentrating on the k-space center, which is considered to hold the majority of contrast information and hence any relevant dynamic change. Typically, in dynamic studies, one full resolution reference image is acquired prior to contrast administration. Following contrast injection, a series of reduced resolution images (keyhole data) is acquired. The full resolution data sets are constructed using the center of k-space provided by keyhole data and the periphery is reconstructed using the full resolution reference image. The application of the keyhole approach, in studies involved with a dynamic contrast, has allowed for an increase in the temporal resolution of acquisitions [2].

Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) contrast utilizes the reduction in the bulk water signal following exchange with solute protons after saturation at the solute’s offset frequency [3]. Specific examples of solutes of interest for which an endogenous CEST effect has been visualized includes amide groups [4, 5], hydroxyl groups found in glycogen (glycoCEST) [6], and more pertinent to this work, hydroxyls in glycosaminoglycans (GAG) for gagCEST [7–9]. The concept of gagCEST has been applied in vivo at 3T with a potential for the evaluation of the content of GAG in articular cartilage and intervertebral discs (IVDs). In particular, Ling et al. introduced gagCEST as a potential tool for understanding the osteoarthritis-associated loss of GAG [7]. Kim et al. demonstrated gagCEST’s potential to monitor GAG-related changes in IVD degeneration [8].

The analysis of the CEST effect in MRI traditionally involves the acquisition of images following saturation at sequential offsets over a range of frequencies that includes the offset associated with the solute of interest (e.g. +1ppm for –OH groups). The signal intensity as a function of saturation offsets constitutes a Z-spectrum. Quantitative analysis of the Z-spectra, and hence the CEST contrast, is based on the calculation of the magnetization transfer ratio asymmetry (MTRasym), which is typically the saturated signal (Isat) at the positive offset subtracted from the saturated signal at the corresponding negative offset and normalized using the signal from an unsaturated image (Iunsat), e.g. for hydroxyl protons: MTRasym(1ppm)=[Isat(−1ppm)−Isat(+1ppm)]/Iunsat [5]. This form of analysis is based on the assumptions that the Z-spectrum is not shifted (i.e. by B0 inhomogeneities) and the effects on the Z-spectrum from magnetization transfer are symmetrical. The latter problem is a standard assumption, to which we will also adhere. The former, i.e. shifts in the Z-spectra due to B0, can be corrected using several techniques, in particular, using water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) [10]. WASSR involves the collection of Z-spectra using a saturation preparation of lower power than that used to acquire data for CEST Z-spectra. Thus, the WASSR Z-spectra are thought to be the result of direct water saturation only. The minimum in the WASSR Z-spectrum corresponds to the true bulk water resonance and is used to correct shifts caused by B0 inhomogeneities.

Collection of the images, for both CEST and WASSR, may prove time consuming (depending on acquisition parameters) and in vivo are more likely to become susceptible to motion. In this work, it is proposed that the total time for Z-spectra acquisition can be reduced through implementation of the keyhole technique. There are three broadly defined approaches for reconstruction of reduced keyhole data to the resolution of a high-resolution image: substitution, weighted substitution, and generalized series (GS) [11]. Here, these techniques are adapted for OH-CEST and are evaluated in vitro. The best-performing approach is demonstrated in vivo.

Experimental Methods

For the in vitro experiments, a phantom was made up consisting of: dextrose and saline in 50ml conical tubes; 20% and 10% (w/w) chondroitin sulfate (Sigma Aldrich) in micro-centrifuge tubes (GAG phantoms) and a sample of bovine nasal cartilage (BNC) suspended in Fomblin® (Ausimont). In vivo images of the right knee were acquired initially from a 36-year-old female volunteer, along with 2 younger volunteers (27 and 32 year-old males), under IRB approval of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

All of the MR experiments were carried out on a 3T scanner (GE Signa Excite) using a transmit/receive knee coil (IGC-Medical Advances Inc.). The saturation schemes for collection of Z-spectra consisted of Gaussian shaped pulses and are further outlined in Table 1. A fast-spin-echo (FSE) imaging sequence was applied with the following parameters: echo-train length (ETL) = 16; FOV = 11×11/14×14cm2 (phantom/in vivo); slice thickness = 6/4mm; TE/TR = 8/2000ms.

Table 1.

Acquisition times for the full and reduced matrix datasets used in the application of the keyhole CEST technique.

| Acquisition type | RF Saturation train | Frequency offset range (min:interval:max) [Hz] | Matrix size | Acquisition time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEST Z-spectra | 5 pulses; B1 ~ 1.5μT | −600:50:600 | 128 × 128 | 6mins 44s |

| 128 × 64 | 3mins 24s | |||

| 128 × 32 | 1min 44s | |||

| WASSR Z-spectra | 1 pulse; B1 ~ 0.1μT | −240:20:240 | 128 × 128 | 6mins 44s |

| 128 × 64 | 3mins 24s | |||

| 128 × 32 | 1min 44s |

High resolution reference images without pre-saturation were acquired with the same scan parameters, but with the ETL increased by a factor of 2 or 4 to account for any respective reduction in matrix size. To account for any variation in the signal-to-noise ratio from the reduction of the acquisition matrix, a low resolution unsaturated image was also acquired as part of the keyhole data. This was keyhole reconstructed to form a high resolution unsaturated image, Iunsat and used in calculation of the MTRasym. Unless stated otherwise, all CEST data was corrected for B0 inhomogeneity using WASSR.

Reconstruction Methods

The Keyhole CEST technique was evaluated using three different methods for reconfiguration of the under sampled keyhole data to match the resolution of the reference image: scaled, weighted substitution, and GS. Reference data was obtained from the high resolution unsaturated image. The first method, scaled substitution of the keyhole data, as opposed to direct substitution used in dynamic imaging, is achieved by taking a ratio of the maximum in k-space signal from the reduced dataset to the signal from the reference (unsaturated) k-space data. For each frequency offset this ratio is multiplied by the high resolution, unsaturated k-space data prior to direct substitution of the central part with the keyhole data:

| (1) |

where Skey and Sref are the keyhole and reference (unsaturated and high-resolution) data, respectively; Nr is the number of keyhole phase encodes.

The second method, weighted substitution, makes use of another high-resolution image obtained following direct water saturation (i.e. saturation applied at 0Hz). In this method the peripheral k-space data are made up from a weighted combination of the unsaturated signal (w1Sunsat) and the saturated signal (w2Ssat=0Hz). The coefficients w1 and w2, for each offset frequency, can be determined by a least squares fitting of the following equation for values of k, at which the signal from keyhole data Skey are acquired:

| (2) |

In this way, high spatial frequency information is available from the two extremes of contrast that exist within the series. Thus there is a reduction in the discontinuity between Sref and Skey data associated with saturation of water, and more information is provided on which the reconstruction of images from keyhole data is based. This method might be advantageous for reconstructions involving different types of tissue (i.e. fat and cartilage), when only one type (of interest) is saturated whilst a significant signal from the other exists.

In the third method, Generalized Series modeling theory is applied to reconstruct an image, IGS from reduced encoding data in terms of sinusoidal basis functions [12]:

| (3) |

The basis functions are formed from the high resolution reference image, Iref so that:

| (4) |

The GS coefficients cn are thus calculated to reflect the modulation in contrast provided by Skey. In this way high spatial-frequency data is recovered by the GS model from the combination of a high resolution reference, Sref that is adjusted through cn, such that over the range of k values for which Skey has been acquired:

| (5) |

These separate keyhole reconstruction techniques were applied in k-space on a line-byline basis proceeding along the frequency encoding direction. Since any reduction only involved the phase encoding steps, the above methods were also examined following application of a 1D Fourier Transform (FT) to the k-space data along the frequency encoding direction (pseudo k-space).

Glyco- and gag- CEST maps from –OH groups were formed using the pixel-by-pixel calculation of the average MTRasym between 0.6 and 1.4ppm (i.e. 80 to 180Hz at 3T). These maps were masked based on signal intensity (to exclude those values lower than the mean of the noise plus 3 standard deviations), as well as on the WASSR maps (to exclude frequency shifts higher than 150Hz associated with lipid components).

Results

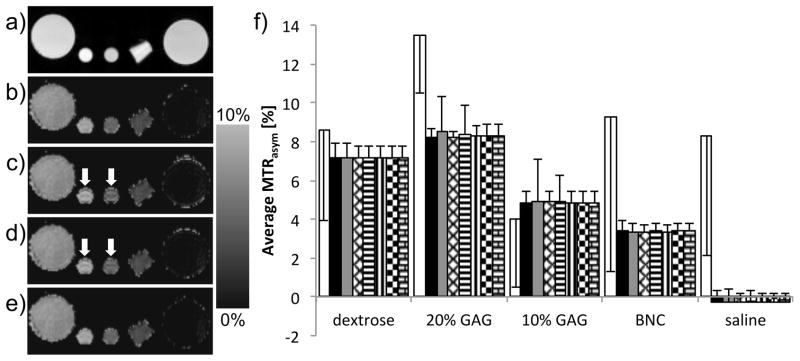

As a preliminary evaluation of Keyhole CEST, a Z-spectrum dataset acquired at full resolution (128×128) was artificially reduced by a factor of 2 along the phase encoding dimension (to 128×64) and reconstructed back to full size using the three different methods outlined in the Reconstruction Methods section. Figure 1 shows evaluation of the different reconstruction methods using a comparison of the mean and standard deviation in CEST values based on ROIs from images of the phantom setup. The results from the full (128×128) CEST dataset with no B0 correction (white columns in Fig. 1f) have high standard deviations and their values are nonsensical compared to that following correction by WASSR. The B0 shift calculated by WASSR over all the phantoms ranged from −167 to +17Hz. Therefore WASSR data acquired at full resolution (128×128) was also applied for correction of the reconstructed data. The mean and standard deviation in CEST contrast (WASSR corrected) from the full resolution dataset are used as a “gold standard”. Although all of the methods produce comparable CEST values, the standard deviation using the scaled and weighted substitution techniques are larger in the GAG samples (Fig. 1f). Moreover, Gibbs ringing effects are apparent in the corresponding CEST maps (arrows in Figs. 1c–d). These effects are not apparent and standard deviations are comparable using the scaled and weighted substitution of the pseudo k-space data following 1D FT. The Generalized Series technique provides consistent results, comparable to full resolution, when applied to either standard k-space or the pseudo k-space. Hence, GS is used in the remaining Keyhole CEST experiments.

Figure 1.

a) An unsaturated image of the phantom setup with (from left to right) dextrose, 20% GAG, 10% GAG, BNC and saline samples. b) OH-CEST map using the full 128 × 128 dataset. OH-CEST maps using Z-spectra data artificially reduced to 128 × 64 and reconstructed to 128 × 128 using the c) scaled, d) weighted substitution technique, or e) GS. Arrows point at Gibbs ringing artifacts. f) Chart of OH-CEST contrast from maps using uncorrected full (white), full (black), scaled (grey), scaled after 1D FT (diamond), weighted substitution (horizontal stripes), weighted substitution after 1D FT (vertical stripes), GS (checkered), and GS after 1D FT (brick) data reconstructions, with error bars of standard deviation. The OH-CEST was calculated using the average MTRasym from 0.6 to 1.4ppm.

Next the use of keyhole reconstruction, applied not only to CEST data but also in combination with data acquired for WASSR, was examined. To account for experimental variations at least partially, separate acquisitions were performed, not the artificial reduction in matrix size as used earlier. From an initial acquisition matrix of 128 × 128, the number of phase encoding steps was reduced by a factor of 2 to 64 and then by a factor of 4 to 32. Reduced datasets relating to both the CEST and WASSR Z-spectra were acquired and GS was used to reconstruct the data for CEST and WASSR separately or in combination. The average shift in B0, as calculated by WASSR, is (−21±41)Hz using both the full data and reconstructed keyhole datasets acquired at lower resolution. In Figure 2a quantitative values taken from the OH-CEST contrast maps formed with the keyhole data are compared with that from the full 128 × 128 acquisition. In all of the cases, the difference between CEST contrast using the full dataset and that reconstructed from 128 × 64 keyhole data is smaller or equal to the difference between the full and 128 × 32 datasets. However, excluding the GAG samples, any difference to the CEST contrast from the full data is smaller than the one standard deviation from the mean value. The GAG samples show the largest variation in mean value and standard deviation upon application of the keyhole technique to either the CEST or WASSR Z-spectra data. Interestingly, the CEST contrast from the GAG samples is more comparable to the results from the 128 × 128 matrix acquisition when the reduction in both the CEST and WASSR datasets are matched. This is attributed to a matching of any partial volume effects that develop. For instance, the B0 shift as calculated by WASSR (using data acquired at full resolution) in the 10% GAG sample is (−144±8)Hz, which compared to a shift of (−25±4)Hz in the BNC sample, represents a greater shift over a smaller area. Partial volume effects from unmatched under sampling would affect the quality of the B0 map particularly in cases of a sharper change in B0. Thus, such a combination of reduced matrix acquisitions was carried forward for in vivo experiments.

Figure 2.

a) A chart of OH-CEST contrast from the phantom setup using CEST data acquired at full resolution (128×128, black) and with reduced matrix sizes (128×64; 128×32). Data from the reduced datasets were reconstructed using the GS technique for Keyhole CEST. The results of the keyhole technique applied to CEST (128×64, vertical stripes; 128×32, horizontal stripes) and WASSR (128×64, checkered; 128×32, brick) Z-spectra acquisitions are shown independently and in combination (128×64, grey; 128×32, white) using the OH-CEST (average MTRasym measured between 0.6 and 1.4ppm). b–d) Images of the BNC sample in the phantom setup, following saturation at an offset frequency of +1.2ppm. The sample is made up from two layers of cartilage (arrows point at separation between layers), which is more evident in the images from b) the full 128 × 128 data, and c) following GS reconstruction of the reduced dataset, compared to the image from d) the reduced 128 × 64 dataset.

Figure 3 shows the results from in vivo imaging of an axial slice through the right knee of a volunteer. The same saturation scheme as used with the phantom setup was applied for full and reduced acquisitions. The CEST map using data acquired with the 128 × 128 matrix shows contrast from cartilage beneath the patella, as well as from regions of muscle (crosses in Fig. 3b). CEST maps produced from the same acquired CEST and WASSR datasets but artificially reduced to 128 × 32 matrix sizes and then reconstructed by GS show similar contrast and shift in B0 (Figs. 3c–f). Quantitative inspection of the gagCEST contrast from a region of cartilage under the patella has the same average value of 1.1% from full and artificially reduced datasets. This comparison is also conducted for separately acquired reduced data (Fig. 3g). The GS reconstructed CEST map demonstrates slightly smaller gagCEST contrast values, but any difference is insignificant when the standard deviation is taken into account.

Figure 3.

a) Unsaturated reference image and b) corresponding CEST map (of average MTRasym between 0.6 to 1.4ppm) from full matrix acquisition of knee (crosses mark areas of muscle), and expanded view (box in b) of c) CEST map and d) shift in B0 from WASSR. Artificial reduction of the matrix size to 128 × 32 produces similar patterns of e) B0 shift and f) CEST contrast. The potential limit in matrix size reduction is observed from a dissipating gagCEST contrast in the linear region adjacent to the condyles (arrows). g) Reconstruction by GS from actual reduced matrix acquisitions of 128 × 32 show gagCEST from the ROI in cartilage beneath the patella.

At the lowest matrix size for keyhole data of 128 × 32, the whole Z-spectrum dataset is acquired in less than 2mins. Figure 4 contains CEST maps from reconstructed keyhole data acquired at this matrix size for the other 2 volunteers. Including the first volunteer, the average gagCEST value from cartilage beneath the patella using the 128 × 32 keyhole data is (0.8±0.4)% (from standard error propagation). Contrast in the CEST map is also visible in the vastus lateralis muscle (cross in Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

a, c) Unsaturated images used as the high-resolution reference for reconstruction of keyhole data acquired through the right knee of two male volunteers. b, d) The corresponding CEST maps of the average MTRasym calculated from reconstructed keyhole data acquired at a matrix size of 128 × 32.

Discussion

The application of keyhole to CEST acquisitions holds potential in several ways: (i) reducing the total scan time; (ii) keeping the total scan time constant, but reducing the number of phase encodes and increasing TR thus allowing reduction in average SAR from compounding of pre-saturation modules; (iii) the reduction in scan time might be used to acquire more frequency offsets per Z-spectrum, just as keyhole has been shown to allow for increased temporal resolution [2].

From Figure 1, the application of Keyhole CEST is seen to be dependent upon the method of reconstruction. A difference exists between the results from scaled and weighted substitution reconstructions applied to the k-space data and (pseudo) k-space data following a 1D FT applied in the non-reduced direction. This is attributed to the signal from the pseudo k-space at the periphery providing more pertinent information for the resultant image and hence the scaling factors, used in both techniques. The GS approach demonstrated no difference between reconstruction applied to the k-space data or (pseudo) k-space data. This is attributed to the inherent minimized effect from truncation artifacts in GS as compared with substitution methods [11]. Arrows in Figure 1 point to the effect of Gibbs ringing in reconstruction of the reduced dataset using the scaled and weighted substitution techniques. Although this might be alleviated by the application of a smoothing filter prior to recombination of the keyhole data, empirically GS provided quantitative CEST contrast values that remained consistently closer to those from a full dataset. The GS technique also holds potential in reconstruction of asymmetrically acquired data [12].

The results from Figure 2a suggest that Keyhole CEST can be applied for acquisitions not only relating to CEST Z-spectra, but also those used in connection with B0 correction by the WASSR technique [10]. Deviation of the quantitative CEST values from the full dataset is smaller for a reduction in the matrix size by half compared to a quarter. However larger differences are also observed from the GAG samples, which are attributed to the smaller diameter of the micro-centrifuge containers. This emphasizes the limit of reduction in matrix size for Keyhole CEST since the minimum spatial resolution is dictated by the size of the object(s) of interest [11]. The argument for Keyhole CEST in these instances might lie in resolving the ROI under study. For example, the BNC sample in the phantom setup is made up from two layers of cartilage. These two layers are distinguishable in the full and GS reconstructed images, but less so in the reduced dataset (Figs. 2b–d). Further improvement in the technique might be possible by periodic update of high frequency information, as demonstrated in techniques like block regional interpolation scheme for k-space or BRISK [13].

An emphasis in gagCEST at 3T from the phantom setup led us to examine cartilage in the knee. A CEST contrast from areas of muscle is also observed (Figs. 3b, 4b) and can be attributed to glycoCEST, as observed previously [10]. Although contrast in the CEST maps seems to correspond with the areas of muscle in unsaturated reference images, there is a significant blood-flow artifact along the phase encoding direction that passes through the posterior muscles (dashed line in Fig. 3b), which makes quantification unreliable in the adjacent areas. Concentrating on the gagCEST contrast from the cartilage beneath the patella, the average value for the first volunteer (Figure 3) remains consistent at 1.1% despite artificial reduction of the matrix size. Application of Keyhole CEST to reduced matrix acquisitions shows a reduced gagCEST contrast from the cartilage beneath the patella. However the gagCEST value remains within the range from that found in the full dataset (taking standard deviation into account).

In order to substantiate the low gagCEST contrast keyhole data acquired using a 128 × 32 matrix size from 2 younger volunteers was also examined. Again, the contrast observed in the Keyhole CEST maps corresponds to the area of cartilaginous tissue beneath the patella from anatomical images (Fig. 4), and the average CEST value remains at approximately 1%. The images are masked based on the SNR and frequency shift, and the contrast-enhanced areas correspond well with the tissue, which supports that the effects observed, however small, are real. Moreover, when averaged over all three preliminary cases gagCEST in articular cartilage shows consistency with an average value of (0.8±0.4)%. Overall, these gagCEST in vivo results are discouraging for practical application to the knee at 3T. A larger contrast, as observed by Ling et al. in vitro [7], might be achieved through a higher field, smaller saturation BW and longer saturation times alleviating the problems of direct saturation associated with CEST close to the on-resonance frequency. The higher CEST contrast observed in vivo by Ling et al. can be attributed to differences in processing (no B0 correction was performed in that study) and different saturation schemes. Despite the small effect sizes observed in vivo, the consistency in combination with in vitro phantom experiments demonstrates the utility of the Keyhole CEST technique.

Under sampling by asymmetric half-Fourier acquisitions as opposed to use of the keyhole technique can be used to speed up acquisitions [14]. Perman et al. reported on specific comparison of the half-Fourier and keyhole techniques [15]. Although the work recommends the use of asymmetric half-Fourier, reduction in the phase-encodes by such a technique is limited to approximately a factor of 2. The results in vivo from under sampling by a factor of 4 using Keyhole CEST shows values that are comparative to those obtained using data acquired at full resolution (with error taken into account). Reasonable under sampling factors are dictated (as stated earlier) by the size of the object(s) of interest. The detrimental effect of the loss in image resolution is observed from a dissipating gagCEST contrast in the linear region adjacent to the condyles (arrows in Figs. 3c, f).

Keyhole CEST in this instance is applied to data acquired from a FSE sequence, but this work serves only as a demonstration of its applicability. Thus Keyhole CEST can potentially be applied to most sequences, but for more exotic acquisition schemes the method of sampling must be taken into account. For instance, in order to account for the acquisition scheme in the FSE sequence, the echo-train length of the unsaturated image was increased in proportion to the matrix size reduction. This work has explored reduction along the phase encoding direction in Cartesian acquisitions. There is potential for the development of this approach into non-Cartesian methods but this requires further investigation of the reconstruction techniques, particularly if the sampling pattern results in a reduction of the matrix along more than one direction.

Conclusion

The keyhole CEST technique is demonstrated for applications involving OH-CEST at 3T both in phantoms and in vivo. Experiments in vitro show the GS technique to provide a stable reconstruction of the reduced datasets for consistent CEST contrast values. When applied for B0 correction by WASSR, Keyhole CEST is found to be more accurate if a reduction in the matrix size is applied to both CEST and WASSR acquisitions. The CEST values in vivo also remain consistent in moving from full to artificial and actual reduced matrix datasets. An average contrast of (0.8±0.4)% is calculated from a region of cartilage beneath the patella using Keyhole CEST applied to 128 × 32 matrix size acquisitions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank M. Farley, R. M. Akhavan and Prof. D. Burstein (BIDMC, Boston) for assistance with BNC samples and helpful discussions. Also, we recognize A. J. Madhuranthakam and F. Kourtelidis for help with sequence development and volunteer scans. The research was supported in part by the NIH grant R21 EB009425.

Bibliography

- 1.Hu X, Parrish T. Reduction of field of view for dynamic imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1994 Jun;31(6):691–4. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910310618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandra S, Liang ZP, Webb A, Lee H, Morris HD, Lauterbur PC. Application of reduced-encoding imaging with generalized-series reconstruction (RIGR) in dynamic MR imaging. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 1996;6(5):783–97. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880060512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolff SD, Balaban RS. NMR imaging of labile proton exchange. Journal of magnetic resonance. 1990;86:164–169. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones CK, Schlosser MJ, van Zijl PCM, Pomper MG, Golay X, Zhou J. Amide proton transfer imaging of human brain tumors at 3T. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2006 Sep;56(3):585–92. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou J, Zijl P. Chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging and spectroscopy. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 2006 May;48(2–3):109–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Zijl PCM, Jones CK, Ren J, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. MRI detection of glycogen in vivo by using chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging (glycoCEST) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007 Mar;104(11):4359–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700281104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ling W, Regatte RR, Navon G, Jerschow A. Assessment of glycosaminoglycan concentration in vivo by chemical exchange-dependent saturation transfer (gagCEST) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008 Mar;105(7):2266–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707666105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim M, Chan Q, Anthony M-P, Cheung KMC, Samartzis D, Khong P-L. Assessment of glycosaminoglycan distribution in human lumbar intervertebral discs using chemical exchange saturation transfer at 3 T: feasibility and initial experience. NMR in biomedicine. 2011 Mar;(2010) doi: 10.1002/nbm.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saar G, Zhang B, Ling W, Regatte RR, Navon G, Jerschow A. Assessment of glycosaminoglycan concentration changes in the intervertebral disc via chemical exchange saturation transfer. NMR in Biomedicine. 2011 doi: 10.1002/nbm.1741. January, p. n/a-n/a, Jul. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim M, Gillen J, Landman BA, Zhou J, van Zijl PCM. Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2009 Jun;61(6):1441–50. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bishop JE, Santyr GE, Kelcz F, Plewes DB. Limitations of the keyhole technique for quantitative dynamic contrast-enhanced breast MRI. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 7(4):716–23. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880070418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang ZP, Lauterbur PC. An efficient method for dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 1994 Jan;13(4):677–86. doi: 10.1109/42.363100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doyle M, Walsh EG, Blackwell GG, Pohost GM. Block regional interpolation scheme for k-space (BRISK): a rapid cardiac imaging technique. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1995 Feb;33(2):163–70. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGibney G, Smith MR, Nichols ST, Crawley A. Quantitative evaluation of several partial Fourier reconstruction algorithms used in MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1993 Jul;30(1):51–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910300109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perman W, Heiberg E. Half-Fourier, Three-dimensional Technique for Dynamic Contrast-enhanced MR Imaging of Both Breasts and Axillae: Initial Characterization of Breast Lesions. Radiology. 1996 doi: 10.1148/radiology.200.1.8657924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]