Abstract

PURPOSE

Domestic violence is prevalent among women using primary health care services in Lebanon and has a negative effect on their health, yet physicians are not inquiring about it. In this study, we explored the attitudes of these women regarding involving the health care system in domestic violence management.

METHODS

We undertook a qualitative focus group study. Health care professionals in 6 primary health care centers routinely screened women for domestic violence using the HITS (Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream) instrument. At each center, 12 women who were screened (regardless of the result) were recruited to participate in a focus group discussion.

RESULTS

Most of the 72 women encouraged involvement of the health care system in the management of domestic violence and considered it to be a “socially accepted way to break the silence.” Women expected health care professionals to have an “active conscience”; to be open minded, ready to listen, and unhurried; and to respect confidentiality. Additionally, they recommended mass media and community awareness campaigns focusing on family relationships to address domestic violence.

CONCLUSIONS

Addressing domestic violence through the health care system, if done properly, may be socially acceptable and nonoffensive even to women living in conservative societies such as Lebanon. The women in this study described characteristics of health professionals that would be conducive to screening and that could be extrapolated to the health care of immigrant Arab women.

Keywords: domestic violence, health care system, women, Lebanon, Arab world, screening, primary health care, culture, battered women, spouse abuse

INTRODUCTION

Domestic violence is prevalent worldwide and associated with considerable morbidity and mortality.1,2 Women exposed to domestic violence are more likely to have physical symptoms, poor pregnancy outcomes, sexually transmitted infections, and elective abortions.3–6 Such consequences lead to poorer physical and mental health, more hospitalizations, greater use of outpatient care for acute problems, and less preventive care.7–10

Although numerous medical associations, governmental agencies, and advocacy groups recommend routinely screening for or inquiring about domestic violence,11,12 many physicians, even in developed countries, do not follow these recommendations13 for various reasons, including lack of knowledge, inadequate training, and fear of offending patients.14

Several studies have been conducted in developed countries to identify women’s attitudes toward routine screening and disclosure of domestic violence in health care settings. A systematic review of 20 peer-reviewed quantitative studies concluded that 43% to 85% of female respondents were in favor of universal screening for intimate partner violence.15 Another systematic review of 84 qualitative and quantitative studies focusing on screening for intimate partner violence revealed that women, including victims of violence, would actually endorse screening for such violence under certain conditions: assurance of privacy, a nonjudgmental clinician, and provision of a rationale for the purpose of the screen.16 In addition, female patients in the United States, regardless of violence exposure, strongly encourage physicians to ask about domestic violence in a direct and caring manner.17,18

Results of studies in the United Kingdom, United States, and Sweden have been similar. Generally, women’s attitudes toward involvement and responses from the health care system can be grouped into 3 categories depending on factors at various levels. At the personal level, readiness, self-esteem, and fear of increased abuse play a role in a woman’s ability to disclose domestic violence.19,20 At the health professional level, female survivors emphasize the importance of the professional asking about domestic violence in an atmosphere of safety and support, with provision of information to reduce suspicion about the reason for such inquiry and minimize stigma. At the organizational level, women consider lack of time during the visit as well as an uninterested physician as major barriers to disclosing domestic violence.19,21,22 Many women also allude to the lack of good referral systems and coordination between professionals and community resources.23,24 In addition, the high cost of medical care and long waiting periods are considered to be barriers to proper management of domestic violence in health care organizations.22

Despite the consistency of findings coming from western countries, findings may differ in studies conducted in Arab countries. Arab culture emphasizes family solidarity, modesty, and reputation (honor); disclosing domestic violence to a physician may be viewed as wrong and a form of family betrayal.25,26 In addition, despite the recent increase of interest in addressing domestic violence in the Arab world, most research remains rather limited and focused on risk factors for spousal abuse. Population-based survey data on the prevalence and consequences of domestic violence are available only from a few countries in the region.27 This general lack of data is surprising given the high social and economic cost of domestic violence.28

The reported prevalence of domestic violence in different Arab countries (23%–35%) falls within the international range.29–31 In Egypt and Jordan, about 1 in every 3 married women has been beaten at least once by her husband.30 Current physical abuse was found among 23% of women randomly selected from primary care centers in Aleppo, Syria.32 In Lebanon, 35% of women using primary health care centers were found to have experienced domestic violence.31

Moreover, there is no societal consensus for action against domestic violence in Arab countries. One study found that 80% of Arab men and women asserted that abuse of a wife is not a criminal act, and some considered it legitimate and acceptable.33 In a recent review of regional literature, Boy and Kulczycki concluded that domestic violence is severe and chronically underreported; there are few legal, social service, or health care resources for victims and survivors, and there is such widespread tolerance of domestic violence by both men and women that “most victims are unable or unwilling to seek help from legal authorities or from health care providers.”29

Because of these social and system barriers in the Arab world, physicians miss opportunities to identify and assist women who are suffering.34 For example, interviews with clinicians reveal that, although they suspect the presence of domestic violence or even frequently encounter survivors, they do not commonly ask or screen for domestic violence in their practice.35 The health care system is thus seldom involved.

It is, therefore, prudent to explore whether cultural differences play a role in shaping women’s disposition toward the involvement of health care professionals in addressing domestic violence in Arab countries. As in many developing countries, there are no established community services, and policies and laws that protect women are largely lacking.

In this study, we explored Lebanese women’s opinions of and attitudes about primary health care clinics taking a proactive role in addressing domestic violence, and their comfort and satisfaction with discussing domestic violence in this setting. We also explored women’s expectations about how the health care system can meet the needs of domestic violence victims.

METHODS

We used a phenomenologic, qualitative focus group design to elicit women’s perceptions about and attitudes toward involvement of the health care system in domestic violence. We conducted the study in primary care and social development community centers of the Ministry of Social Affairs in Lebanon. There are 89 centers in 6 governorates (Mohafaza) serving low- to middle-income populations. We selected 1 center in each governorate that met 2 criteria: the center had at least 20 female patient visits per day, and its health care professionals had prior training on domestic violence.

These 6 primary care centers implemented a domestic violence protocol during the study so that all women visiting the centers were asked and had discussion about domestic violence. According to the protocol, health care professionals asked all female patients about domestic violence using the HITS (Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream) interview. Any woman acknowledging domestic violence was offered a hotline number to a specialized domestic violence center. Results of the screening were kept confidential from the research team.

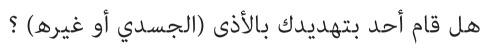

HITS is a validated 4-question domestic violence screening tool (Table 1).36 It was translated into Arabic by the principal investigator (J.U.), back-translated to test translation accuracy, and then piloted with 5 female patients to make sure questions were understood and not offensive. We did not compare the translated HITS to the original HITS on measurement outcomes because the purpose of the questionnaire in this study was only to familiarize female patients with domestic violence inquiry and referral in a medical setting.

Table 1.

The HITS Screening Tool for Domestic Violence in English and Arabic

| HITS – English version | |||||||

| Please read each of the following activities and fill in the circle that best indicates the frequency with which your partner acts in the way depicted. | |||||||

| How often does your partner? | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Fairly often | Frequently | ||

| 1. Physically hurt you | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| 2. Insult or talk down to you | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| 3. Threaten you with harm | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| 4. Scream or curse at you | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| HITS – Arabic version | |||||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |  |

|||

| ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |  |

|||

| ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |  |

|||

| ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |  |

|||

HITS = Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream.

Adapted with permission from Sherin et al.36

We recruited participants between March 2 and 13, 2009. A clinic social worker approached all female patients older than 18 years of age when they entered the clinic, to explain the focus group discussion and obtain verbal informed consent and contact information. Focus group participants were later randomly selected from this group.

We prepared a focus group interview guide in Arabic. Topics included (1) opinions, attitudes, and expectations about involving primary health care in domestic violence management; (2) opinions about domestic violence inquiry and the HITS questionnaire; and (3) perceived barriers to involving the health care system and suggested solutions.

The focus groups met at each health center in a patient education classroom. The facilitator and moderator were social workers with prior focus group training and experience; the facilitator worked in a nongovernmental domestic violence institution.

Focus group discussions were taped, transcribed verbatim by the facilitator, and reviewed for accuracy by 1 investigator. To identify common themes, transcripts were reviewed separately by 2 research assistants and then compared. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus after discussion with the principal investigator (J.U.). Thematic analysis was used, grouping responses into common themes, grouping themes into topics, and analyzing trends according to participant characteristics. After completing 6 focus group discussions, the research team agreed that saturation of ideas had been reached.

This study was approved by the American University of Beirut Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

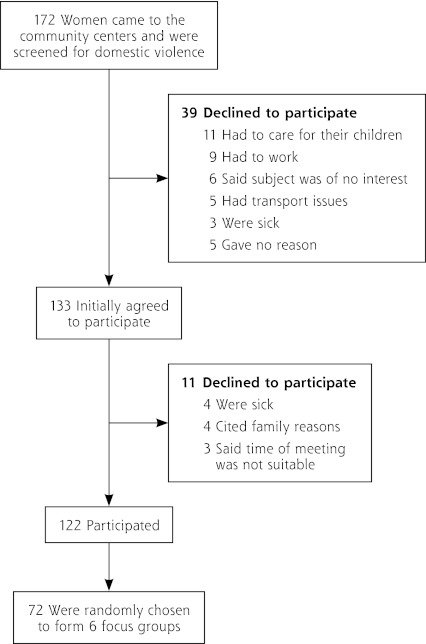

A total of 172 women were seen at the 6 health centers during the study period; 133 consented to participate in a focus group discussion, of whom 72 were later invited to participate (Figure 1). Each group contained 12 women. Participants came from a low and middle socioeconomic background and ranged in age from 20 to 55 years. Sixty-one were married, 10 were single, and 1 was divorced. Four women were illiterate, 36 had received some elementary education, 20 had received some secondary education, and 12 were university graduates.

Figure 1.

Recruitment of women from community health centers into focus groups.

Five topics emerged from the focus group discussions (Table 2): Should health care play a role in domestic violence intervention? How will men react to a health care role in domestic violence? How should health care professionals inquire about domestic violence? How should health care professionals respond to disclosure of domestic violence? And finally, what cultural and community barriers exist and how can they be overcome? Each topic is discussed in greater detail below.

Table 2.

The Voices of Lebanese Women: Key Topics and Themes

| Health care’s role in domestic violence intervention | |

| Encouragement | “I knew I am not the first woman nor going to be the last woman to be assaulted.” |

| “I felt that I have enough courage to speak out.” | |

| Promise of change | “A step forward to help women” |

| “We should start talking about it so that we can start thinking of solutions.” | |

| “Break the silence.” | |

| Feeling supported/relieved | “I feel that someone is caring.” |

| “Psychological satisfaction as I got relieved from a major burden” | |

| “When the woman victim of violence has the courage to talk openly and frankly about what is happening in her life, she will be relieved.” | |

| “Her morale and psyche will be better.” | |

| “She has so many problems on her head and should not face them alone.” | |

| Confidentiality | “They (health care professionals) don’t know me and this makes me feel more comfortable.” |

| Intrusion | “Interference in private affairs” |

| “Outsiders should not get involved in personal issues.” | |

| “The woman should solve her problems alone.” | |

| Shame | “I felt ashamed.” |

| Men’s response | |

| Indifference | “It is the last of their worries.” |

| “Even when there is infertility problem in the family, he doesn’t check himself as he thinks his manhood will be affected.” | |

| Encouragement | “Men may look at it positively as there is a professional involvement aiming at improving his relations with his wife.” |

| “Not all men are bad; there are men who are active in community problems.” | |

| Denial | “Men will not accept that women have started to gain rights.” |

| “Men like to look like angels; such a step will destroy this image.” | |

| Increase in violence | “He may forbid her from coming to the health center.” |

| “He may beat her anyway; women are not expected to make scandals and expose the house privacy.” | |

| “He may beat the doctor.” | |

| Inquiry about domestic violence | |

| First establish the physician-patient relationship | “So the woman would feel more confident talking” and “trust is being built” |

| “He knows when he is not in a hurry and has enough time to listen.” | |

| Physicians are trusted | “The doctor has seen my naked body so why can’t I talk to him about my problems?” |

| “I trust my doctor more than I trust my neighbor, I talk to him and he usually guides me to what is best for me to do.” | |

| Social workers are trusted | “She has the right to interfere in family problems.” |

| ”She can get into the house and the brother or husband would not feel she is against him.” | |

| Responding to domestic violence disclosure | |

| Support | “He can provide power and energy.” |

| “Although he cannot abolish violence and sometimes cannot provide solutions, he can listen to her and provide her with medications that help her.” | |

| Guidance and awareness | “The woman should find out how to solve her issues but she can refer to him for advice.” |

| “Unlike other people, the doctor provides advice with care and confidence, he relieves the suffering and makes the woman feel better.” | |

| “He can make her aware that she is suffering from the violence she is living in because she may not recognize this.” | |

| “Refer [victimized women] to professional organizations or psychological support team.” | |

| Action | ”He can write a report and the aggressor can be punished.” |

| “He can talk to the man and ask him why he is doing this [being violent].” | |

| “Communicate with the police.” | |

| Competence is expected | “My neighbor was beaten by her brother, but in the hospital, the treating doctor did not ask her about the bruises; she was upset with the physician and felt unprotected.” |

| Cultural and community barriers and suggested solutions | |

| Cultural barriers | “The society forces women to wear a mask.” |

| “Culture and tradition forbid us from speaking.” | |

| “The way women are brought up, they are not allowed to raise their voice.” | |

| “Ridiculous, we are subject to insults even on the street.” | |

| Fear of scandal | “It is not easy to face the scandal.” |

| “She will be the talk of the town if she speaks.” | |

| Free or low-cost resources | “Women don’t have many resources.” |

| Community awareness campaign | Highlight “improving family relationships” rather than “fighting against domestic violence.” |

| “Give lectures on healthy relations within the family and specifically among couples so that the violent man doesn’t feel he is being targeted.” | |

Health Care’s Role in Domestic Violence Intervention

Most women were enthusiastic about the health care system addressing domestic violence. They considered the health clinic a better place to talk confidentially about problems vs with family or in their neighborhood. As one woman said, “they don’t know me and this makes me feel more comfortable.” They viewed the clinic as a safe place where women can take an initial step to bring attention to domestic violence and break the silence.

When the health care system becomes involved in domestic violence, participants expected women to feel encouraged, supported, and relieved. Others considered it a promise of change; as one participant observed, it will be “a step forward to help women” that will “show women they are not alone.”

Some participants expressed concerns about a health system role in domestic violence. Some women, mostly from rural communities, reported feeling “ashamed,” surprised, and shocked when asked about domestic violence, while others considered the problem personal and questioned “interference in private affairs.”

Men’s Response

When asked about the reaction of men to health care playing role in domestic violence, women’s comments reflected 4 themes. Some women believed men will be indifferent; “it is the last of their worries,” one commented. Others were hopeful that men would be supportive advocates in the community or that a man would work on “improving his relationship with his wife.” Some expected men to react with denial, anger, and violence—“men like to look like angels; such a step will destroy this image” and hence, “he may beat her anyway. Women are not expected to make scandals and expose the house privacy.” Finally, some expressed concern for physician safety, saying, for instance, “he may beat the doctor.” Several participants suggested that men also be asked routinely about domestic violence because “there are men who are subject to violence too.”

Inquiring About Domestic Violence

Participants discussed in detail how to implement inquiry about domestic violence in the health clinic. Most women emphasized that physicians should ensure confidentiality and establish a good physician-patient relationship before asking about domestic violence so “trust is being built” and “the woman will feel more confident talking.” Moreover, the health care professional should have ample time to discuss the matter: “he knows when he is not in a hurry and has enough time to listen.” Some suggested that inquiry about domestic violence be included in the first interview, but others believed that the physician and patient may need more time to build rapport. Several participants encouraged physicians to ask about injuries and expressed disappointment that a treating doctor had neglected in the past to inquire about bruises from a domestic violence assault.

Diverse opinions emerged about who should ask about domestic violence. Many women preferred to be asked by the physician. “The doctor has seen my naked body so why can’t I talk to him about my problems?” one woman explained. “I trust my doctor more than I trust my neighbor; I talk to him and he usually guides me to what is best for me to do,” another said. Some women expressed reservations about physician involvement because they did not consider the patient’s emotional well-being as part of the physician’s role—“the doctor’s role is to treat diseases.” Many women preferred that a social worker ask about domestic violence because social workers can gain the trust of the husband: “she has the right to interfere in family problems…” and “she can get into the house and the brother or husband would not feel she is against him.” Participants discouraged domestic violence inquiry by nurses because nurses are not skilled in dealing with family issues and a nurse might “do harm as it is not her domain.”

Women expressed diverse opinions about professional and personal characteristics of the physician. Participants recommended domestic violence inquiry by family doctors, gynecologists, or psychologists, but some identified 2 barriers concerning psychologists: “psychologists are expensive” and “people may think I am crazy if I go there.”

Many women felt equally at ease discussing domestic violence with male and female physicians. A subgroup of women, mostly from rural areas, reported that they communicate better with female physicians. A few objected to male physicians asking about domestic violence because “they will be allies” with the abusive spouse. In contrast, some women preferred a male physician, viewing men as more knowledgeable, with stronger personalities and “he can understand the man better and may be able to explain to me his [the husband’s] behavior.”

Most women felt that physician age did not matter, “it is the experience that counts.” But some preferred discussing domestic violence with a young doctor, explaining, for example, “new graduates with updated medical information are more open minded” and put the patient at ease. Others preferred an older doctor who is “more experienced” and “more knowledgeable,” and noted, “the husband will be less suspicious if the doctor is old.”

Responding to Domestic Violence Disclosure

Participants offered diverse advice about how health care professionals should respond to a woman’s disclosure of domestic violence. Women expected the physician to be thorough and competent, and to provide emotional and material support, “although he cannot abolish violence and sometimes cannot provide solutions.” Some participants expected the physician to take action such as “writing a report so the aggressor can be punished,” “communicating with police,” or “talking to the man and asking him why he is doing this [being violent].” On the other hand, many participants emphasized respecting the woman’s autonomy by “not pushing the woman to get information” and “letting her decide for herself.” Participants expected social workers and nurses to listen, counsel, and raise awareness. Finally many participants noted the value of continuity, saying, for example, “be ready to follow up with the woman.”

Cultural and Community Barriers and Suggested Solutions

Should primary care clinics begin routinely asking women about domestic violence, women identified the larger community and cultural context as an obstacle to domestic violence disclosure, noting “the culture and traditions forbid us from speaking” and “women…are not allowed to raise their voice.” Some women feared scandal and community rebuke, commenting “it is not easy to face the scandal”; this was a fear grounded in lived experience, as several women described disclosing domestic violence to a health care professional only to encounter later a negative reaction from the community for “revealing the secret.” Women also voiced concerns about increased violence and losing children to abusive husbands. Finally, participants recommended that domestic violence services be free or low cost because “women don’t have many resources.”

Some women recommended that any new program to address domestic violence at the health centers should be preceded by a mass media and community awareness campaign. The messages in this campaign should highlight “improving family relations” rather than “fighting against domestic violence” because this positive theme would speak to both women and men. Community campaigns were thought to be especially important in rural areas, where family privacy and confidentiality are highly valued.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study we know of that reflects Arab women’s voices about the health care system’s role in domestic violence identification and intervention. Although Arab women are generally expected to balance their needs and well-being against preservation of family reputation and loyalty to one’s husband,37 they still suggested that inquiring about domestic violence in health care settings is a “socially accepted way to break the silence” and may “herald societal changes leading to an improved situation for women.” Moreover, consistent with previous research in other cultures,17,18,38–40 most Lebanese women in this study favored a health care system that works to prevent domestic violence by routinely asking women about it and referring them to community resources. Also consistent with prior research, participants emphasized the importance of a trusting physician-patient relationship, confidentially, a caring and unhurried demeanor, emotional and material support, good listening skills, competent and thorough medical care, respect for the woman’s autonomy, and continuity. These qualities characterize a good physician-patient relationship39,41 and effective conditions for domestic violence inquiry.17,18,39–41

Women in this study identified several barriers to creating an effective health care response to domestic violence that are comparable to those of women in developed countries: cost of services, failure of confidentiality, and fears of retaliation and increased violence. Yet, the approach to these barriers and its impact differ in Lebanon and other developing countries, where most ambulatory services are provided for a fee that would be unaffordable to many abuse victims. Existing community-based domestic violence services are currently provided on a volunteer basis and may be overwhelmed if the health care system implements routine screening and referral. Because of the scarcity of resources, women would justifiably worry about being blamed by family and community for revealing a family secret and causing the family to fall apart. This form of blaming the victim is a major obstacle for domestic violence interventions, especially in patriarchal, collectivist social contexts, prevalent in the Arab region.

Fear of retaliation by the spouse may also be more pronounced among Arab women, whose concerns would not be limited to increasing violence, but also to being separated from their children, a strategy commonly used by violent spouses31 and condoned by the society.

Acknowledging these societal barriers, many Lebanese women had the insight to recognize that involving health care in domestic violence management would be a “socially accepted way to break the silence” and address the issue. Using “health” as a doorway for social reform has not been voiced by women in other studies but could be used to advocate for change in addressing inequality between sexes.

On the other hand, Lebanese women in this study voiced concerns and ideas that may be specific to their social and cultural context. Being aware of these opinions is important and helpful for physicians attending to and treating Arab immigrants in the United States, United Kingdom, or other western countries as well. It is known that cultural barriers within the immigrant community can restrict women’s use of domestic violence services.42,43

Women in rural communities expressed shame and embarrassment when asked about domestic violence, preferring to discuss it with a female physician. This finding suggests that health care systems may need to adapt domestic violence interventions to the local community with particular care given to urban vs rural differences in women’s lived experience and willingness to disclose. Women from the local community could be recruited to guide and inform a clinic’s domestic violence response.

Women recommended that improvements in the health system’s response to domestic violence should be preceded and accompanied by mass media and community education campaigns focusing on healthy family relationships. This is the first report we are aware of in which women, when asked about the health care response to domestic violence, have recommended adopting strategies for community-level intervention and social change. Yet, they advised that those campaigns be labeled as “protecting family unity” or “improving family communication” rather than addressing domestic violence, indicating that they have a good grasp of their society’s restrictions and anticipated reactions, and could identify ways to overcome them, reminiscent of survivors’ behaviors.

This study has several limitations, most of which are related to focus group discussions. The findings cannot be generalized to all Lebanese women owing to the small sample size and recruitment from selected primary health care centers. The fact that some women declined to participate might have introduced bias into the results. Finally, the sensitivity of domestic violence as a topic might have introduced bias.

In conclusion, most Lebanese women in this study welcomed and encouraged the involvement of the health care system in the identification of domestic violence. They did not, however, believe the health care system alone can reduce or end domestic violence, and therefore recommended community interventions including public awareness and media campaigns, to change knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and social norms. This study sets the ground for further research to explore women’s opinions about domestic violence screening in health care settings, especially in Arab cultures, and to plan interventions accordingly.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the courage and openness of the Lebanese women who participated in focus group discussions, KAFA (Enough Violence and Exploitation) for their help in data collection, the Lebanese Ministry of Social Affairs for assistance with recruitment, and the World Health Organization-EMRO for financial support.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

Funding support: This study was supported by the World Health Organization–EMRO.

References

- 1.Ambuel B, Phelan B, Hamberger LK, Wolff M. Healthcare can change from within: a sustainable model for intimate partner violence intervention and prevention. In: Banyard VL, Edwards VJ, Kendall-Tackett K, eds. Trauma and Physical Health: Integrating Trauma Practice in Primary Care. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C; WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence: an observational study. Lancet. 2008;371(9619):1165–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coker AL, Smith PH, Bethea L, King MR, McKeown RE. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(5):451–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Díaz-Olavarrieta C, Campbell J, García de la Cadena C, Paz F, Villa AR. Domestic violence against patients with chronic neurologic disorders. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(6):681–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leserman J, Li Z, Drossman DA, Hu YJ. Selected symptoms associated with sexual and physical abuse history among female patients with gastrointestinal disorders: the impact on subsequent health care visits. Psychol Med. 1998;28(2):417–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, et al. The “battering syndrome”: prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123 (10):737–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cronholm PF, Fogarty CT, Ambuel B, Harrison SL. Intimate partner violence. Am Fam Phys. 2011;83(10):1165–1172 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tjaden PG, Thoennes N. Extent, Nature, and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tollestrup K, Sklar D, Frost FJ, et al. Health indicators and intimate partner violence among women who are members of a managed care organization. Prev Med. 1999;29(5):431–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wisner CL, Gilmer TP, Saltzman LE, Zink TM. Intimate partner violence against women: do victims cost health plans more? J Fam Pract. 1999;48(6):439–443 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Academy of Family Physicians Family and intimate partner violence and abuse [policy statement]. 2004. http://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/policy/policies/f/familyandintimatepartner-violenceandabuse.html Accessed Jan 31, 2012

- 12.Intimate partner violence. Committee Opinion No. 518. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(2 Pt 1):412–417 http://www.acog.org/~/media/Committee%20Opinions/Committee%20on%20Health%20Care%20for%20Underserved%20Women/co518.ashx?dmc=1&ts=20120131T2324405207 Accessed Jan 31, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez MA, Bauer HM, McLoughlin E, Grumbach K. Screening and intervention for intimate partner abuse: practices and attitudes of primary care physicians. JAMA. 1999;282(5):468–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottemoeller M. Ending violence against women. Pop Rep. 2009;27(4)1–44 http://www.infoforhealth.org/pr/l11edsum.shtml Accessed Jan 31, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramsay J, Richardson J, Carter YH, Davidson LL, Feder G. Should health professionals screen women for domestic violence? Systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325(7359):314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Todahl J, Walters E. Universal screening for intimate partner violence: a systematic review. J Marital Fam Ther. 2011;37(3):355–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamberger LK, Ambuel B, Marbella A, Donze J. Physician interaction with battered women: the women’s perspective. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7(6):575–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamberger LK, Ambuel B, Guse C. Racial differences in battered women’s experiences and preference for treatment from physicians. J Fam Viol. 2007;22(5):259–265 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerbert B, Johnston K, Caspers N, Bleecker T, Woods A, Rosenbaum A. Experiences of battered women in health care settings: a qualitative study. Women Health. 1996;24(3):1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gielen AC, O’Campo PJ, Campbell JC, et al. Women’s opinions about domestic violence screening and mandatory reporting. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(4):279–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liebschutz J, Battaglia T, Finley E, Averbuch T. Disclosing intimate partner violence to health care clinicians—what a difference the setting makes: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodríguez MA, Sheldon WR, Bauer HM, Pérez-Stable EJ. The factors associated with disclosure of intimate partner abuse to clinicians. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(4):338–344 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang JC, Decker MR, Moracco KE, Martin SL, Petersen R, Frasier PY. Asking about intimate partner violence: advice from female survivors to health care providers. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59(2):141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stenson K, Saarinen H, Heimer G, Sidenvall B. Women’s attitudes to being asked about exposure to violence. Midwifery. 2001;17(1):2–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haj-Yahia MM. Wife abuse and battering in the sociocultural context of Arab society. Fam Process. 2000;39(2):237–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haj-Yahia MM. Attitudes of Arab women toward different patterns of coping with wife abuse. J Interpers Violence. 2002;17(7):721–745 [Google Scholar]

- 27.UN Women (United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women). Violence against women prevalence data: surveys by country. March 2011. http://www.endvawnow.org/uploads/browser/files/vaw_prevalence_matrix_15april_2011.pdf Accessed Aug 10, 2011

- 28.United Nations Population Fund and International Center for Research on Women. Intimate Partner Violence. High Costs to Households and Communities. 2009. http://www.icrw.org/files/publications/Intimate-Partner-Violence-High-Cost-to-Households-and-Communities.pdf Accessed Jan 31, 2012

- 29.Boy A, Kulczycki A. What we know about intimate partner violence in the Middle East and North Africa. Violence Against Women. 2008;14(1):53–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El Zanaty F, Hussein EM, Sahwaky GM, Way AA, Kishor S. Egypt Demographic and Health Survey. Cairo, Egypt: National Population Council; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Usta J, Farver JA, Pashayan N. Domestic violence: the Lebanese experience. Public Health. 2007;121(3):208–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maziak W, Asfar T. Physical abuse in low-income women in Aleppo, Syria. Health Care Women Int. 2003;24(4):313–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Douki S, Nacef F, Belhadj A, Bouasker A, Ghachem R. Violence against women in Arab and Islamic countries. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2003;6(3):165–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Usta J, Farver JA, Zein L. Women, war, and violence: surviving the experience. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(5):793–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Rapid Appraisal of Reproductive Health Services in Lebanon. Beirut, Lebanon: UNFPA; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li XQ, Zitter RE, Shakil A. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. 1998;30(7):508–512 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haj-Yahia MM, Sadan E. Issues in intervention with battered women in collectivist societies. J Marital Fam Ther. 2008;34(1):1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bacchu L, Mezey G, Bewley S. Women’s perceptions and experiences of routine enquiry for domestic violence in a maternity service. BJOG. 2002;109(1):9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feder GS, Hutson M, Ramsay J, Taket AR. Women exposed to intimate partner violence: expectations and experiences when they encounter health care professionals: a meta-analysis of qualitative studies. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(1):22–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez MA, Quiroga SS, Bauer HM. Breaking the silence. Battered women’s perspectives on medical care. Arch Fam Med. 1996; 5(3):153–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Battaglia TA, Finley E, Liebschutz JM. Survivors of intimate partner violence speak out: trust in the patient-provider relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):617–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abu-Ras W. Cultural beliefs and service utilization by battered Arab immigrant women. Violence Against Women. 2007;13(10):1002–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kulwicki A, Aswad B, Carmona T, Ballout S. Barriers in the utilization of domestic violence services among Arab immigrant women: perceptions of professional, service providers and community leaders. J Fam Viol. 2010;25(8):727–735 [Google Scholar]