Abstract

The regulation of organ size in higher organisms is a fundamental issue in developmental biology. In flowering plants, a phenomenon called “compensation” has been observed where a cell proliferation defect in developing leaf primordia triggers excessive cell expansion. As a result, final leaf size is not significantly reduced compared to that expected from the reduction in leaf cell numbers. Recent genetic studies have revealed several key features of the compensation phenomenon. Compensation is induced either cell autonomously or non-cell autonomously depending on the trigger that impairs cell proliferation; a certain type of compensation is induced only when cell proliferation is impaired beyond a threshold level. Excessive cell expansion is achieved by either an increased cell expansion rate or a prolonged period of cell expansion via genetic pathways that are also required for normal cell expansion. These results indicate that cell proliferation and cell expansion are coordinated through multiple pathways during leaf size determination. Further classification of compensation pathways and their characterization at the molecular level will provide a deeper understanding of organ size regulation.

Keywords: angustifolia3, cell expansion, cell proliferation, compensation, extra-small sisters, fugu, oligocellula, organ size

Organ size regulation is an essential process for the optimal growth and appropriate function of multicellular organisms. The size of aerial lateral organs in plants, i.e., leaves and floral organs, is determined by the number and size of constituent cells since the growth of these organs is determinate. Therefore, quantitative recognition of size-related parameters and developmental decisions is required to control the kinetic aspects of cell proliferation and cell expansion. The molecular mechanisms underlying cell proliferation and postmitotic cell expansion have been investigated extensively, mainly through the characterization of the cell cycle and endocycle in which multiple rounds of DNA replication occur without cell division (Inzé and De Veylder, 2006; Breuer et al., 2010). In addition to these cell cycle regulators, a number of genes have been identified over the last decade that regulate the size of lateral organs through the modulation of cell proliferation and/or cell expansion (Gonzalez et al., 2009; Krizek, 2009; Micol, 2009). Many of these genes encode regulatory factors that act at the transcriptional (Mizukami and Fischer, 2000; Kim and Kende, 2004; Horiguchi et al., 2005, 2009; White, 2006; Usami et al., 2009; Ichihashi et al., 2010) or posttranscriptional level (Disch et al., 2006; Li et al., 2008; Usami et al., 2009), and some are involved in cell–cell communication (Strabala et al., 2006; Anastasiou et al., 2007; Eriksson et al., 2010). In addition to such cell level regulation, cell proliferation and postmitotic cell expansion must be coordinated to establish an organ of the appropriate size. Although the mechanisms underlying such coordination are still largely unknown, recent molecular genetic studies have begun to provide some insight. In this review, we focus on the phenomenon termed “compensation,” wherein a decrease in cell number in a leaf caused by a genetic defect leads to an enhanced cell expansion. This phenomenon serves as a key to understanding organ size regulation (Tsukaya, 2002, 2008; Beemster et al., 2003). When considering the mechanisms of organ size, two contrasting theories exist. Organismal perspective is based on the idea that organ size is determined independently from constituent cells (Kaplan, 2001). On the other hand, cell perspective employs an idea that cell is a basic unit that determines organ size. We employ neo-cell perspective that leaf size determination is mediated by cell–cell communication (Tsukaya, 2002). Indeed recently we demonstrated that cell–cell communication is a key mechanism behind compensation (Kawade et al., 2010).

The earliest report describing compensation was by Haber (1962) in a study characterizing leaf development using gamma-irradiated wheat grains. Cell division is severely compromised and overall leaf growth is significantly reduced in developing seedlings following gamma irradiation. Despite this, however, leaf morphogenesis occurs and cells in the leaf show larger expansion than control cells; thus, the reduction in cell proliferation triggers excessive cell expansion (Haber, 1962). In the modern molecular genetics era, compensation has been observed in transgenic plants in which the cell cycle was inhibited through manipulation of core cell cycle regulators such as CDKA;1 (Hemerly et al., 1995) and KIP-related protein2 (KRP2; De Veylder et al., 2001), and in mutants defective in positive regulators of cell proliferation, such as AINTEGUMENTA (ANT; Mizukami and Fischer, 2000) and ANGUSTIFOLIA3/GRF-INTERACTING FACTOR1 (AN3/GIF1; Kim and Kende, 2004; Horiguchi et al., 2005). Many more instances have since been reported, mainly from Arabidopsis thaliana (Table 1) and other plant species such as Oryza sativa (Barrôco et al., 2006) and Antirrhinum majus (Delgado-Benarroch et al., 2009).

Table 1.

Examples of compensation-exhibiting mutants and transgenic plants.

| Gene | Type of mutation | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| AE7 | Loss-of-function | Yuan et al. (2010) |

| AN3/GIF1 | Loss-of-function | Kim and Kende (2004), Horiguchi et al. (2005) |

| ANT | Loss-of-function | Mizukami and Fischer (2000) |

| CDKA;1 | Dominant negative | Hemerly et al. (1995) |

| CYCD3 | Loss-of-functions of CYCD3;1, CYCD3;2, and CYCD3;3 | Dewitte et al. (2007) |

| ER | Loss-of-function | Horiguchi et al. (2006), Ferjani et al. (2007) |

| ETG1 | Loss-of-function | Takahashi et al. (2008) |

| FAS1 | Loss-of-function | Exner et al. (2006), Ramirez-Parra and Gutierrez (2007) |

| FAS2 | Loss-of-function | Exner et al. (2006) |

| FUGU1 | Recessive mutation | Ferjani et al. (2007) |

| FUGU2 | Recessive mutation | Ferjani et al. (2007) |

| FUGU3 | Dominant mutation | Ferjani et al. (2007) |

| FUGU4 | Dominant mutation | Ferjani et al. (2007) |

| FUGU5 | Recessive mutation | Ferjani et al. (2007) |

| GPA1 | Loss-of-function | Ullah et al. (2001) |

| ICK1 | Overexpression | Wang et al. (2000) |

| KRP2 | Overexpression | De Veylder et al. (2001) |

| MAX2 | Loss-of-function | Horiguchi et al. (2006) |

| miR396 | Overexpression | Liu et al. (2009), Rodriguez et al. (2010) |

| OLI | Loss-of-functions of OLI2 and OLI5 or OLI2 and OLI7 | Fujikura et al. (2009) |

| PFL2 | Loss-of-function | Ito et al. (2000) |

| RPS6A | Loss-of-function | Horiguchi et al. (2011) |

| RPS21B | Loss-of-function | Horiguchi et al. (2011) |

| RPS28B | Loss-of-function | Horiguchi et al. (2011) |

| SMP | Epimutation | Clay and Nelson (2005) |

| SWP | Loss-of-function | Autran et al. (2002) |

| UVI4/PYM | Loss-of-function | Hase et al. (2006) |

Defective Cell Proliferation Triggers Compensation

Changes in the number and size of leaf cells in response to the alterations of core cell cycle regulator activities have a seesaw-like relationship; enhanced and reduced cell proliferation negatively and positively affects postmitotic cell expansion, respectively. This relationship has held true in several cases in which the expression levels of core cell cycle regulators were manipulated. Transition from the cell cycle to endocycle occurs during leaf development. Differentiating cells often undergo several rounds of endocycle and expansion in a manner correlated with nuclear DNA content (Melaragno et al., 1993). A precocious transition from the cell cycle to endocycle increases the number of rounds of endocycle and causes leaves to have fewer and larger cells (Boudolf et al., 2004; Verkest et al., 2005). Conversely, CYCD3;1 and E2Fa overexpression prolongs cell proliferation and inhibits the endocycle, resulting in the inhibition of cell expansion that usually takes place in association with endocycling (De Veylder et al., 2002; Dewitte et al., 2003).

In these instances, the cause is clearly altered cell proliferation activity. However, in some specific cases, cell number and size are regulated at the whole-plant level. The more and smaller cells (msc) mutants show increased cell number and reduced cell size in leaves (Usami et al., 2009). The msc phenotype seems to be the opposite of the prototypic compensation. This suggests that an increase in cell number is able to negatively affect cell size during leaf development. However, msc genes are not directly involved in the regulation of cell proliferation. Rather, they are associated with heteroblasty in which various leaf traits such as leaf shape, cell number, cell size, and trichome distribution progressively change during the transition from juvenile to adult phases (Usami et al., 2009). In the wild-type, cell number increases and cell size decreases in leaves formed at higher nodes. On the other hand, in msc mutants, such developmental changes take place faster than in the wild-type, indicating that the msc phenotype is caused by accelerated heteroblasty and not increased cell proliferation (Usami et al., 2009). The msc1-D mutant has an miR156 resistance mutation in the SQUAMOSA-PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE15 (SPL15) gene, while msc2 and msc3 are new alleles of PAUSED (PSD) and SQUINT (SQN), respectively (Usami et al., 2009).

In the above instances increase or decrease in cell number is associated with decrease or increase of cell size, respectively as if they have a seesaw-like relationship. However, certain instances of compensation, at least of the prototype one, have different characteristics than this seesaw-like relationship. In the case of ant- and an3-induced compensation, cell number is fewer, but cell size is larger compared to the wild-type (Mizukami and Fischer, 2000; Horiguchi et al., 2005). In these cases, the cause of compensation is clearly defective cell proliferation, as ANT and AN3 are expressed in young leaf primordia with active cell proliferation and are gradually downregulated as the leaf matures (Horiguchi et al., 2005; Kang et al., 2007). In contrast to these loss-of-function phenotypes, their overexpression promotes cell proliferation in leaf primordial; however, this does not cause inhibition of cell expansion (Mizukami and Fischer, 2000; Horiguchi et al., 2005). These observations suggest that for ANT and AN3 compensation is induced only when their loss-of-function impairs cell proliferation. It is not yet clear what mechanistic differences determine whether unidirectional or seesaw-like compensation occurs, but the next issues to be resolved will involve identification of the transcriptional targets of AN3 and ANT and how these transcriptional regulators control cell proliferation.

These observations indicate that altered cell proliferation is a trigger for compensation. Conversely, is it possible that altered postmitotic cell expansion influences cell proliferation in the same leaf primordium? There is no clear evidence in support of this possibility; among the mutants with phenotypes characterized by either fewer but larger cells or more but smaller cells, no known genes have specific functions in postmitotic cell expansion. Rather, several lines of evidence support the suggestion that altered postmitotic cell expansion does not affect cell proliferation. There are mutants with a cell expansion-specific phenotype, but a normal number of leaf cells. Both rotunda2 (ron2) and rpl4d enhance cell expansion in leaves without any changes in cell number (Cnops et al., 2004; Horiguchi et al., 2011). Similarly, the bigpetal (bpe) mutation increases epidermal cell size without affecting cell number in petals (Szécsi et al., 2006). A number of extra-small sisters (xs) mutants show specific reductions in final cell size in leaves (Fujikura et al., 2007a). Furthermore, the levels of ATHB16 and ARGOS-LIKE (ARL) expression are negatively and positively correlated with epidermal cell size in leaves, respectively, without affecting cell number (Wang et al., 2003; Hu et al., 2006). These observations suggest that modulation of cell expansion in many cases does not trigger compensation through cell proliferation. Taken together, these observations indicate that some specific types of compensation are unidirectionally induced only when cell number is decreased.

How is Compensation Triggered?

As discussed above, a decrease in cell proliferation specifically induces compensation. This raises the question of how compensation is triggered. The observations that rotundifolia4-D (rot4-D) and growth regulating factor5 (grf5) decrease cell number in the leaves, but fail to induce compensation provide insight into this question (Narita et al., 2004; Horiguchi et al., 2005). The grf5 phenotype is especially important as GRF5 is an interacting partner of AN3, and both of these molecules promote cell proliferation (Horiguchi et al., 2005). The degrees of reduction in cell number in these mutants are milder than those of ant or an3 (Narita et al., 2004; Horiguchi et al., 2005), suggesting that there is a threshold level of cell number or cell proliferation activity below which compensation is triggered. This was confirmed by two experiments. In the first experiment, a series of AN3-silenced lines were used. The leaf cell number was reduced at various levels according to the strength of AN3 silencing, but compensation was triggered only when cell number was substantially reduced (Fujikura et al., 2009). In the second experiment, a series of oligocellula (oli) mutants were used. The leaves of these oli mutants had a reduced number of normal-sized cells (Fujikura et al., 2009). In contrast, oli2 oli5 and oli2 oli7 double mutants had fewer leaf cells than the parental single mutants and showed compensation (Fujikura et al., 2009). These three OLI genes encode a yeast NOP2 homolog that is involved in ribosome biogenesis (OLI2) and two ribosomal protein RPL5 paralogs (OLI5 and OLI7; Fujikura et al., 2009). These findings were also consistent with the observation that strong ribosomal protein-defective mutants exhibit compensation (Ito et al., 2000; Horiguchi et al., 2011). Similar observations were made using KRP2 and miR396. KRP2 inhibits CDKA;1 activity, while miR396 targets many members of the GRF family (De Veylder et al., 2001; Rodriguez et al., 2010). Overexpression of these genes impairs cell proliferation and induces compensation, but only in mutants showing strong expression (Verkest et al., 2005; Rodriguez et al., 2010). The existence of a threshold for the induction of compensation suggests that there is an unknown mechanism of sensing cell proliferation activity and modulating cell expansion during differentiation.

How are Proliferating and Differentiating Cells Linked?

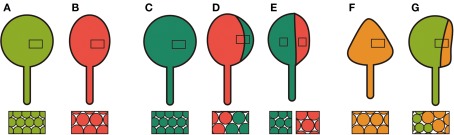

Since proliferating cells and differentiating cells coexist in the same leaf primordium during leaf development (Donnelly et al., 1999; Kazama et al., 2010), it is possible that a defect in cell proliferation affects postmitotic cell expansion in a non-cell autonomous manner. Alternatively, mitotic cells showing unusually low cell proliferation activity may enhance their own cell expansion after exiting the mitotic cycle. Studies of genetic chimeras showed both of these suggestions to be true depending on the trigger of the defects in cell proliferation. When chimeric leaves with an3 mutant sectors and AN3-overexpressing sectors were examined using the CRE-loxP system, compensation was seen irrespective of leaf cell genotype (Figures 1A–D; Kawade et al., 2010). This suggested that a mobile signal is transmitted from the an3 sectors to neighboring cells to enhance cell expansion. Interestingly, this signal seems unable to move laterally beyond the midvein in the leaf primordia, as a longitudinal half-and-half chimera separated by the midvein exhibited compensation only in the an3 half (Figure 1E). On the other hand, KRP2-induced compensation occurred in a cell autonomous manner when wild-type sectors and KRP2-overexpressing sectors coexisted in leaves (Figures 1A,F,G; Kawade et al., 2010). There are two possible interpretations regarding how individual cells cause compensation on overexpression of KRP2. Since mitotic cells overexpressing KRP2 are already larger than wild-type (Ferjani et al., 2007), such a difference may be maintained until maturation of the leaves. The other interesting interpretation is that cells “remember” very low levels of cell proliferation activity and show enhanced cell expansion based on this “memory” when they enter the postmitotic phase of leaf development (Fujikura et al., 2007b; Kawade et al., 2010). Thus, compensation appears to be a heterogeneous phenomenon, with multiple inputs and pathways leading to enhanced cell expansion.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of chimeric leaves and cell size. (A) A wild-type leaf. (B) An an3 leaf with cells larger than wild-type. (C) An AN3-overexpressor in the an3 background with normal-sized cells. (D) A chimeric leaf consisting of AN3-overexpressing (deep green, right) and an3 (red, left) cells. Cells are larger than wild-type regardless of genotype. (E) A half-and-half chimera. An AN3-overexpressing sector containing midrib (deep green, right) showed maintenance of normal cell size, while an adjacent an3 sector (red, left) contained cells larger than those in the AN3-overexpressing sector. (F) A KRP2-overexpressing leaf with cells larger than wild-type. (G) A chimeric leaf consisting of wild-type (light green, left) and KRP2-overexpressing (yellow, right) sectors. Cells in the KRP2-overexpressing sector were larger than those in the wild-type sector.

How is Cell Expansion Enhanced?

When compensation is triggered, differentiating cells show enhanced cell expansion through at least two different mechanisms. One route is the endocycle. In some compensation-exhibiting mutants, such as fasciata1 (fas1), fugu2, and struwwelpeter (swp), the ploidy distribution of leaves shifts to a higher level (Autran et al., 2002; Exner et al., 2006; Ferjani et al., 2007; Ramirez-Parra and Gutierrez, 2007). Timing of transition from mitotic cycle to endocycle can vary in different cells in the same tissue. Occurrence of endoreduplication coincides with cell expansion in epidermis (Beemster et al., 2005). This may explain correlation between ploidy level and cell size (Traas et al., 1998). In yeast, ploidy-associated changes in gene expression have been demonstrated and many of which encodes cell surface components or their regulators (Wu et al., 2010). However, it is not clear whether similar transcriptional changes occur in plants.

The second route is a ploidy-independent process. This is an ambiguous classification as no molecular components involved in this process have been identified and it does not mean that different compensation-exhibiting mutants without an increased ploidy level share a common mechanism of enhanced cell expansion. Some compensation-exhibiting mutants have a relatively normal ploidy level [e.g., erecta (er); Ferjani et al., 2007] or even a reduced ploidy level (e.g., KRP2-overexpressors; De Veylder et al., 2001). In tetraploid Arabidopsis, palisade cell size observed from the paradermal viewpoint is 1.6-fold larger than that in diploid counterparts (Tsukaya, unpublished). The palisade cells in an3 are about 1.5-fold larger than those of the wild-type, but the increase in ploidy level is not significant (Ferjani et al., 2007; Fujikura et al., 2007), suggesting that a ploidy-independent process mediates part of the enhanced cell expansion. In the case of an3-induced compensation, three suppressor mutations, xs1, xs2, and xs5, were identified (Fujikura et al., 2007a). These xs mutants have normal numbers of smaller leaf cells in comparison to the wild-type, suggesting that genes involved in normal cell expansion are also required during compensation (Fujikura et al., 2007a). These xs mutants have normal (xs1), reduced (xs2), and increased (xs5) ploidy levels compared with wild-type (Fujikura et al., 2007a). At present, these phenotypes are difficult to interpret. It is possible that a certain ploidy level may be required to establish compensation, but a further increase in ploidy level is not necessarily required, at least in an3-induced compensation. These results also suggest that in certain genetic backgrounds, ploidy-associated and ploidy-independent compensation pathways are induced simultaneously. This puzzling situation would be solved when these XS genes are cloned and such experiments are in progress.

A comparative study using several compensation-exhibiting mutants, including fugu and an3, also suggested that multiple physiological pathways are involved in enhanced cell expansion during compensation (Ferjani et al., 2007). Most compensation-exhibiting mutants examined, such as fugu2 and an3, show faster leaf cell expansion compared to the wild-type (Ferjani et al., 2007). One exception is fugu5 in which the duration of cell expansion is extended compared to the wild-type (Ferjani et al., 2007). Thus, induction, transmission, and response processes of compensation are linked by multiple parallel pathways and further studies are required to determine whether these pathways are interconnected.

Does Compensation Have Physiological and Developmental Roles?

In many cases, compensation does not fully restore leaf area. Thus, compensation is unlikely to be a mechanism that maintains an organ at a constant size. Compensation may play a role in an environmental response. When wild-type plants are irradiated with ultraviolet B (UV-B), the number of epidermal cell decreases and compensation is induced (Wargent et al., 2009). Curiously, uv resistance locus8 (uvr8), which was recently shown to be defective in a UV-B receptor (Rizzini et al., 2011), shows reduced cell number in response to UV-B irradiation but does not show enhanced cell expansion (Wargent et al., 2009). An increase in ploidy level confers UV-B tolerance in both tetraploid Arabidopsis and UV-B-insensitive4 (uvi4) mutants (Hase et al., 2006). Furthermore, the UV-B response includes induction of the PHR1 gene encoding photolyase through downregulation of DP-E2F-LIKE1 (DEL1), which is an endocycle repressor (Radziejwoski et al., 2011). These reports suggest that compensation associated with increased ploidy level may reflect part of the UV-B resistance mechanism.

In addition to the possibility that compensation reflects an environmental response, it may also represent a normal developmental mechanism for cell expansion. For example, the linkage of cell proliferation and postmitotic cell expansion may achieve fine-tuning of organ size, inhibition of premature entry into differentiation, or rapid change from proliferating to differentiating status. Although these possibilities remain to be confirmed, the establishment of the genetic framework of compensation over the past decade will enable these issues to be tested. For identification of the molecular components involved in compensation, more precise measurements and observations of cellular behavior in relation to developmental timing during compensation are needed in future experiments. The results that will be obtained from these approaches will help to elucidate underlying molecular mechanisms to gain insight into the physiological/developmental significance of compensation.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all members of the compensation team for their efforts and discussion. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Creative Scientific Research (No. 18GS0313 to Hirokazu Tsukaya) and Scientific Research on Priority Areas (No. 19060002 to Hirokazu Tsukaya).

References

- Anastasiou E., Kenz S., Gerstung M., MacLean D., Timmer J., Fleck C., Lenhard M. (2007). Control of plant organ size by KLUH/CYP78A5-dependent intercellular signaling. Dev. Cell 13, 843–856 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autran D., Jonak C., Belcram K., Beemster G. T., Kronenberger J., Grandjean O., Inzé D., Traas J. (2002). Cell numbers and leaf development in Arabidopsis: a functional analysis of the STRUWWELPETER gene. EMBO J. 21, 6036–6049 10.1093/emboj/cdf614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrôco R. M., Peres A., Droual A. M., De Veylder L., Nguyen le S. L., De Wolf J., Mironov V., Peerbolte R., Beemster G. T., Inzé D., Broekaert W. F., Frankard V. (2006). The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Orysa; KRP1 plays an important role in seed development of rice. Plant Physiol. 142, 1053–1064 10.1104/pp.106.087056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beemster G. T., Fiorani F., Inzé D. (2003). Cell cycle: the key to plant growth control? Trends Plant Sci. 8, 154–158 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00046-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beemster G. T. S., De Veylder L., Vercruysse S., West G., Rombaut D., Van Hummelen P., Galichet A., Gruissem W., Inzé D., Vuylsteke M. (2005). Genome-wide analysis of gene expression profiles associated with cell cycle transitions in growing organs of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 138, 734–743 10.1104/pp.104.053884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudolf V., Vlieghe K., Beemster G. T. S., Magyar Z., Torres Acosta J. A., Maes S., Van Der Schueren E., Inzé D., De Veylder L. (2004). The plant-specific cyclin-dependent kinase CDKB1;1 and transcription factor E2Fa-DPa control the balance of mitotically dividing and endoreduplicating cells in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16, 2683–2692 10.1105/tpc.104.024398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuer C., Ishida T., Sugimoto K. (2010). Developmental control of endocycles and cell growth in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13, 654–660 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay N. K., Nelson T. (2005). The recessive epigenetic swellmap mutation affects the expression of two step II splicing factors required for the transcription of the cell proliferation gene STRUWWELPETER and for the timing of cell cycle arrest in the Arabidopsis leaf. Plant Cell 17, 1994–2008 10.1105/tpc.105.032771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnops G., Jover-Gil S., Peters J. L., Neyt P., De Block S., Robles P., Ponce M. R., Gerats T., Micol J. L., Van Lijsebettens M. (2004). The rotunda2 mutants identify a role for the LEUNIG gene in vegetative leaf morphogenesis. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 1529–1539 10.1093/jxb/erh165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Veylder L., Beeckman T., Beemster G. T., Krols L., Terras F., Landrieu I., van der Schueren E., Maes S., Naudts M., Inzé D. (2001). Functional analysis of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13, 1653–1668 10.2307/3871392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Veylder L., Beeckman T., Beemster G. T. S., de Almeida Engler J., Ormenese S., Maes S., Naudts M., Van Der Schueren E., Jacqmard A., Engler G., Inzé D. (2002). Control of proliferation, endoreduplication and differentiation by the Arabidopsis E2Fa-DPa transcription factor. EMBO J. 21, 1360–1368 10.1093/emboj/21.6.1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Benarroch L., Weiss J., Egea-Cortines M. (2009). The mutants compacta ähnlich, nitida and grandiflora define developmental compartments and a compensation mechanism in floral development in Antirrhinum majus. J. Plant Res. 122, 559–569 10.1007/s10265-009-0236-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewitte W., Riou-Khamlichi C., Scofield S., Healy J. M., Jacqmard A., Kilby N. J., Murray J. A. (2003). Altered cell cycle distribution, hyperplasia, and inhibited differentiation in Arabidopsis caused by the D-type cyclin CYCD3. Plant Cell 15, 79–92 10.1105/tpc.004838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewitte W., Scofield S., Alcasabas A. A., Maughan S. C., Menges M., Braun N., Collins C., Nieuwland J., Prinsen E., Sundaresan V., Murray J. A. H. (2007). Arabidopsis CYCD D-type cyclins link cell proliferation and endocycles and are rate-limiting for cytokinin responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 14537–14542 10.1073/pnas.0704166104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disch S., Anastasiou E., Sharma V. K., Laux T., Fletcher J. C., Lenhard M. (2006). The E3 ubiquitin ligase BIG BROTHER controls Arabidopsis organ size in a dosage-dependent manner. Curr. Biol. 16, 272–279 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly P. M., Bonetta D., Tsukaya H., Dengler R. E., Dengler N. G. (1999). Cell cycling and cell enlargement in developing leaves of Arabidopsis. Dev. Biol. 215, 407–419 10.1006/dbio.1999.9443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson S., Stransfeld L., Adamski N. M., Breuninger H., Lenhard M. (2010). KLUH/CYP78A5-dependent growth signaling coordinates floral organ growth in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 20, 527–532 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner V., Taranto P., Schönrock N., Gruissem W., Henning L. (2006). Chromatin assembly factor CAF-1 is required for cellular differentiation during plant development. Development 133, 4163–4172 10.1242/dev.02599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferjani A., Horiguchi G., Yano S., Tsukaya H. (2007). Analysis of leaf development in fugu mutants of Arabidopsis reveals three compensation modes that modulate cell expansion in determinate organs. Plant Physiol. 144, 988–999 10.1104/pp.107.099325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikura U., Horiguchi G., Ponce M. R., Micol J. L., Tsukaya H. (2009). Coordination of cell proliferation and cell expansion mediated by ribosome-related processes in the leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 59, 499–508 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03886.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikura U., Horiguchi G., Tsukaya H. (2007a). Dissection of enhanced cell expansion processes in leaves triggered by a defect in cell proliferation, with reference to roles of endoreduplication. Plant Cell Physiol. 48, 278–286 10.1093/pcp/pcm002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikura U., Horiguchi G., Tsukaya H. (2007b). Genetic relationship between angustifolia3 and extra-small sisters highlights novel mechanisms controlling leaf size. Plant Signal. Behav. 2, 378–380 10.4161/psb.2.5.4525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez N., Beemster G. T. S., Inzé D. (2009). David and Goliath: what can the tiny weed Arabidopsis teach us to improve biomass production in crops? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12, 157–164 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber A. H. (1962). Non-essentiality of concurrent cell divisions for degree of polarization of leaf growth. I. Studies with radiation-induced mitotic inhibition. Am. J. Bot. 49, 583–589 10.2307/2439715 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hase Y., Trung K. H., Matsunaga T., Tanaka A. (2006). A mutation in the uvi4 gene promotes progression of endo-reduplication and confers increased tolerance towards ultraviolet B light. Plant J. 46, 317–326 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02696.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemerly A., Engler Jde A., Bergounioux C., Van Montagu M., Engler G., Inzé D., Ferreira P. (1995). Dominant negative mutants of the Cdc2 kinase uncouple cell division from iterative plant development. EMBO J. 14, 3925–3936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi G., Fujikura U., Ferjani A., Ishikawa N., Tsukaya H. (2006). Large-scale histological analysis of leaf mutants using two simple leaf observation methods: identification of novel genetic pathways governing the size and shape of leaves. Plant J. 48, 638–644 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02896.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi G., Gonzalez N., Beemster G. T., Inzé D., Tsukaya H. (2009). Impact of segmental chromosomal duplications on leaf size in the grandifolia-D mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 60, 122–133 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03940.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi G., Kim G. T., Tsukaya H. (2005). The transcription factor AtGRF5 and the transcription coactivator AN3 regulate cell proliferation in leaf primordia of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 43, 68–78 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02429.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi G., Mollá-Morales A., Pérez-Pérez J. M., Kojima K., Robles P., Ponce M. R., Micol J. L., Tsukaya H. (2011). Differential contributions of ribosomal protein genes to Arabidopsis thaliana leaf development. Plant J. 65, 724–736 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04457.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Poh H. M., Chua N.-H. (2006). The Arabidopsis ARGOS-LIKE gene regulates cell expansion during organ growth. Plant J. 47, 1–9 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02750.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichihashi Y., Horiguchi G., Gleissberg S., Tsukaya H. (2010). The bHLH transcription factor SPATULA controls final leaf size in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 252–261 10.1093/pcp/pcp184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzé D., De Veylder L. (2006). Cell cycle regulation in plant development. Annu. Rev. Genet. 40, 77–105 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Kim G.-T., Shinozaki K. (2000). Disruption of an Arabidopsis cytoplasmic ribosomal protein S13-homologous gene by transposon-mediated mutagenesis causes aberrant growth and development. Plant J. 22, 257–264 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00728.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J., Mizukami Y., Wang H., Fowke L., Dengler N. G. (2007). Modification of cell proliferation patterns alters leaf vein architecture in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 226, 1207–1218 10.1007/s00425-007-0567-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan D. R. (2001). Fundamental concepts of leaf morphology and morphogenesis: a contribution to the interpretation of molecular genetic mutants. Int. J. Plant Sci. 162, 465–474 10.1086/320135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawade K., Horiguchi G., Tsukaya H. (2010). Non-cell-autonomously coordinated organ size regulation in leaf development. Development 137, 4221–4227 10.1242/dev.057117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazama T., Ichihashi Y., Murata S., Tsukaya H. (2010). The mechanism of cell cycle arrest front progression explained by a KLUH/CYP78A5-dependent mobile growth factor in developing leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 1046–1054 10.1093/pcp/pcq051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. H., Kende H. (2004). A transcriptional coactivator, AtGIF1, is involved in regulating leaf growth and morphology in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 13374–13379 10.1073/pnas.0404519101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizek B. (2009). Making bigger plants: key regulators of final organ size. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12, 17–22 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. H., Zheng L. Y., Corke F., Smith C., Bevan M. W. (2008). Control of final seed and organ size by the DA1 gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 22, 1331–1336 10.1101/gad.1687308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Song Y., Chen Z., Yu D. (2009). Ectopic expression of miR396 suppresses GRF target gene expression and alters leaf growth in Arabidopsis. Physiol. Plant. 136, 223–236 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01229.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melaragno J. E., Mehrotra B., Coleman A. W. (1993). Relationship between endopolyploidy and cell size in epidermal tissue of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 5, 1661–1668 10.1105/tpc.5.11.1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micol J. L. (2009). Leaf development: time to turn over a new leaf? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12, 9–16 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami Y., Fischer R. L. (2000). Plant organ size control: AINTEGUMENTA regulates growth and cell numbers during organogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 942–947 10.1073/pnas.97.2.942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita N. N., Moore S., Horiguchi G., Kubo M., Demura T., Fukuda H., Goodrich J., Tsukaya H. (2004). Overexpression of a novel small peptide ROTUNDIFOLIA4 decreases cell proliferation and alters leaf shape in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 38, 699–713 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02078.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radziejwoski A., Vlieghe K., Lammens T., Berckmans B., Maes S., Jansen M. A., Knappe C., Albert A., Seidlitz H. K., Bahnweg G., Inzé D., De Veylder L. (2011). Atypical E2F activity coordinates PHR1 photolyase gene transcription with endoreduplication onset. EMBO J. 30, 355–363 10.1038/emboj.2010.313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Parra E., Gutierrez C. (2007). E2F regulates FASCIATA1, a chromatin assembly gene whose loss switches on the endocycle and activate gene expression by changing the epigenetic status. Plant Physiol. 144, 105–120 10.1104/pp.106.094979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzini L., Favory J. J., Cloix C., Faggionato D., O'Hara A., Kaiserli E., Baumeister R., Schäfer E., Nagy F., Jenkins G. I., Ulm R. (2011). Perception of UV-B by the Arabidopsis UVR8 protein. Science 332, 103–106 10.1126/science.1200660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez R. E., Mecchia M. A., Debernardi J. M., Schommer C., Weigel D., Palatnik J. F. (2010). Control of cell proliferation in Arabidopsis thaliana by microRNA miR396. Development 137, 103–112 10.1242/dev.043067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strabala T. J., O'Donnell P. J., Smit A.-M., Ampomah-Dwamena C., Martin E. J., Netzler N., Nieuwenhuizen N. J., Quinn B. D., Foote H. C. C., Hudson K. R. (2006). Gain-of-function phenotypes of many CLAVATA3/ESR genes, including four new family members, correlate with tandem variations in the conserved CAVATA3/ESR domain. Plant Physiol. 140, 1331–1344 10.1104/pp.105.075515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szécsi J., Joly C., Bordji K., Varaud E., Cock J. M., Dumas C., Bendahmane M. (2006). BIGPETALp, bHLH transcription factor is involved in the control of Arabidopsis petal size. EMBO J. 25, 3912–3920 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N., Lammens T., Boudolf V., Maes S., Yoshizumi T., De Jaeger G., Witters E., Inzé D., De Veylder L. (2008). The DNA replication checkpoint aids survival of plants deficient in the novel replisome factor ETG1. EMBO J. 27, 1840–1851 10.1038/emboj.2008.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traas J., Hülskamp M., Gendreau E., Höfte H. (1998). Endoreduplication and development: rule without dividing? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 1, 498–503 10.1016/S1369-5266(98)80042-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaya H. (2002). Interpretation of mutants in leaf morphology: genetic evidence for a compensatory system in leaf morphogenesis that provides a new link between cell and organismal theories. Int. Rev. Cytol. 217, 1–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaya H. (2008). Controlling size in multicellular organs: focus on the leaf. PLoS Biol. 6, e174. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah H., Chen J.-G., Young J. C., Im K.-H., Sussman M. R., Jones A. M. (2001). Modulation of cell proliferation by heterotrimeric G protein in Arabidopsis. Science 292, 2066–2069 10.1126/science.1059040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usami T., Horiguchi G., Yano S., Tsukaya H. (2009). The more and smaller cells mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana identify novel roles for SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE genes in the control of heteroblasty. Development 136, 955–964 10.1242/dev.028613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkest A., Manes C.-L., Vercruysse S., Maes S., Van Der Schueren E., Beeckman T., Genschik P., Kuiper M., Inzé D., De Veylder L. (2005). The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor KRP2 controls the onset of endoreduplication cycle during Arabidopsis leaf development through inhibition of mitotic CDKA;1 kinase complexes. Plant Cell 17, 1723–1736 10.1105/tpc.105.032383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Zhou Y., Gilmer S., Whitwill S., Fowke L. C. (2000). Expression of the plant cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor ICK1 affects cell division, plant growth and morphology. Plant J. 24, 613–623 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00899.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Henriksson E., Söderman E., Henriksson K. N., Sundberg E., Engström P. (2003). The Arabidopsis homeobox gene, ATHB16, regulates leaf development and sensitivity to photoperiod in Arabidopsis. Dev. Biol. 264, 228–239 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wargent J. J., Gegas V. C., Jenkins G. I., Doonan J. H., Paul N. D. (2009). UVR8 in Arabidopsis thaliana regulates multiple aspects of cellular differentiation during leaf development in response to ultraviolet B radiation. New Phytol. 183, 315–326 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02855.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White D. W. (2006). PEAPOD regulates lamina size and curvature in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 13238–13243 10.1073/pnas.0604349103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.-Y., Rolfe P. A., Gifford D. K., Fink G. R. (2010). Control of transcription by cell size. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000523. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z., Luo D., Li G., Yao X., Wang H., Zeng M., Huang H., Cui X. (2010). Characterization of the AE7 gene in Arabidopsis suggests that normal cell proliferation is essential for leaf polarity establishment. Plant J. 64, 331–342 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04326.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]