Abstract

Ribonucleotide reductase (RR), the rate limiting enzyme in the synthesis and repair of DNA, has been studied as a target for inhibition in the treatment of cancer for many years. While some researchers have focused on RR inhibitors as chemotherapeutic agents, particularly in hematologic malignancies, some of the most promising data has been generated in the field of radiosensitization. Early pre-clinical studies demonstrated that the addition of the first of these drugs, hydroxyurea, to ionizing radiation (IR) produced a synergistic effect in vitro, leading to a large number of clinical studies in the 1970–1980s. These studies, mainly in cervical cancer, initially produced a great deal of interest, leading to the incorporation of hydroxyurea in the treatment protocols of many institutions. However, over time, the conclusions from these studies have been called into question and hydroxyurea has been replaced in the standard of care of cervical cancer. Over the last 10 years, a number of well-done pre-clinical studies have greatly advanced our understanding of RR as a target. Those advances include the elucidation of the role of p53R2 and our understanding of the temporal relationship between the delivery of IR and the response of RR. At the same time, new inhibitors with increased potency and improved binding characteristics have been discovered, and pre-clinical and early clinical data look promising. Here we present a comprehensive review of the pre-clinical and clinical data in the field to date and provide some discussion of future areas of research.

Keywords: ribonucleotide reductase, hydroxyurea, triapine, radiosensitizer, ionizing radiation, cervical cancer

Introduction

Ribonucleotide reductase (RR) inhibitors have been studied as radiation sensitizers for over 30 years in both the lab and the clinic. The first of these, hydroxyurea, has been studied in both cervical and head and neck cancers, among others. Although initially promising, many of the clinical trials produced negative results, or those that were difficult to interpret. There has recently been a significant advance in our understanding of this pathway from a number of well-done pre-clinical studies. In addition, the discovery of new RR inhibitors with increased potency and improved binding characteristics has produced a significant increase in interest in this area. This review will synthesize the data detailing the response of RR to ionizing radiation (IR) and will provide a perspective on the use of RR inhibitors as radiosensitizers in the treatment of human cancers. Over the years, many groups have explored the use of RR inhibitors as chemotherapeutics in their own right, or as adjuncts to DNA damaging molecules, particularly in hematologic malignancies. While this area looks promising, this subject will not be reviewed here. Readers are directed to a review by Tsimberidou et al. (2002) and a recent paper by Gojo et al. (2007) for further information.

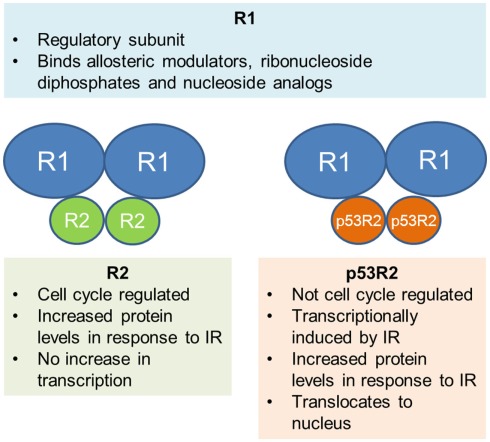

Ribonucleotide reductase is the rate limiting enzyme in the synthesis and repair of DNA and is the only enzyme responsible for the conversion of ribonucleoside diphosphates to deoxyribonucleotide diphosphates, the fundamental building blocks of DNA synthesis and repair. RR is a heterodimeric tetramer comprised of two dimers. R1 (also called RRM1 or M1) is the larger, regulatory subunit that is constitutively expressed throughout the cell cycle. It binds allosteric modulators, ribonucleoside diphosphates, and the nucleoside analogs gemcitabine and fludarabine. There are currently two known smaller subunits that bind R1 to form the active enzyme; R2 (also called RRM2 or M2) and a more recently discovered p53 inducible homolog of the R2 subunit, known as p53R2. Both contain a tyrosine free radical stabilized by a non-heme iron complex that is critical in the reduction of ribonucleotides. R2 is known to be cell cycle regulated, with the highest levels during S phase, however the precise roles of the R2 and p53R2 subunit in the response to IR are an area of active debate, as outlined below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the two heterodimers that form RR. Current evidence for the role of each subunit is summarized.

Given the pivotal role of RR in DNA synthesis and repair, many studies have investigated the effect of DNA damaging agents, including IR, on RR and its subunits. Even so, there is currently still a great deal of controversy surrounding the exact mechanism of RR response to IR. There are two main theories; the first is that the small subunit R2 is up-regulated and provides dNTPs for DNA repair in addition to its usual role in DNA synthesis during S phase. This is supported by a number of studies, including one by Kuo et al., who characterized the response of RR in the human cervical cancer cell line, Caski. They demonstrated an increase in R2 protein levels after treating cells with IR, which was correlated with an increase in RR activity. However, there was no increase in the transcription of R2, implying that the protein increase was due to post-transcriptional regulation (Kuo and Kinsella, 1998). This finding was reinforced by studies that demonstrated DNA damage dependent stabilization of the R2 protein without any change in mRNA after IR exposure in mouse Balb/3T3 cells (Chabes and Thelander, 2000); however it was in contrast to earlier work showing transcriptional activation of the R1 and R2 promoters after exposure to IR in the same cell line (Filatov et al., 1996). Even though the precise mechanism of R2 response to IR damage is unclear, work has shown that human nasopharyngeal cancer cells overexpressing R2 demonstrate a significant increase in radioresistance and fewer DNA double strand breaks (DSB) after exposure to IR (Kuo et al., 2003), confirming the concept that R2 is important in the cellular response to IR.

The second theory involves the p53 inducible subunit, p53R2, first reported by Tanaka et al. They showed that p53R2 was not cell cycle regulated (unlike R2), but was significantly induced after exposure of normal fibroblasts to IR (Tanaka et al., 2000) and was found to translocate to the nucleus, the proposed site of most important dNTP production (R2 did not). In cells that lacked wild-type (WT) p53, there was no induction, indicating that functional p53 was necessary for p53R2 up-regulation. Cells transfected with p53R2 were resistant to DNA damage induced cell death. In agreement with other studies, they found no increase in R2 mRNA, but did not measure protein levels. Additional studies have subsequently shown that p53R2 forms an active complex with R1 (Guitett et al., 2001) and p53R2 protein is increased after IR exposure to p53 WT cell lines. RR activity increased in correlation with the increase in p53R2, however the response of R2 was variable, with decrease in some lines and a moderate increase in the others (Yamaguchi et al., 2001). Finally, other models are possible, including one described by Xue and colleagues. In their study, both subunits were found to bind p53 in human oropharyngeal carcinoma cells, and in response to IR, were released to bind R1 in the nucleus (Xue et al., 2003), highlighting a third possibility in contrast to those previously presented.

Clearly, there is still work to be done in elucidating the response of RR to IR. Many of the differences seen in the studies discussed can likely be attributed to the use of different techniques, materials, and especially cell lines. What should be clear is that RR is involved in the cellular response to IR and targeting it is both rational and likely desirable in enhancing the treatment of cancers with IR. It is likely that both R2 and p53R2 are involved to a different degree in different cancers, with cellular phenotype likely playing a key role in determining their relative significance.

Hydroxyurea

Hydroxyurea (HU) is a hydroxylated analog of urea and was the first RR inhibitor to be extensively studied. It has directed activity at the tyrosine radical moiety of R2 and was first found to be active against cancer cells in 1963 (Stearns et al., 1963). Subsequent experiments in vitro showed that in addition to its direct inhibition of DNA synthesis, it was also a sensitizer of cell killing by X-rays, particularly if given before or after IR (Sinclair, 1968). Later experiments showed that this was also the case in in vivo animal tumor models using isotransplants of spontaneous C3H/He mouse mammary carcinomas (Piver et al., 1972). The total dose of IR to cure 50% of tumors was reduced when HU was combined with fractionated IR, although this effect wasn’t seen with single fraction IR treatments. Given these encouraging pre-clinical results during the 1960–1970s, HU was subsequently examined in a number of clinical trials in a variety of human cancers.

The majority of these trials have occurred in cervical cancer, most commonly in locally advanced disease. In particular, there were a number of prospective randomized controlled trials in the 1970s and 1980s that examined the effect of HU plus radiotherapy vs. radiotherapy alone. The largest of these, a study by Hreshchyshyn et al. and the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) enrolled 190 women with FIGO stage IIIB or IVA cervical carcinoma. HU was administered orally at 80 mg/kg starting on the first day of irradiation and every 3 days thereafter for 12 weeks. Patients received at least 50 Gy minimum tumor dose to the whole pelvis followed by a single brachytherapy treatment of 20 Gy to point A. In spite of the large number of patients enrolled, only 90 were eligible for assessment of response. This was due to ineligibility (wrong stage, wrong cell type, etc.) and those that were inevaluable (refused treatment, periaortic node irradiation, improper field, etc.). The data were impressive, with a complete response (CR) of 68.1% in the HU group vs. 48.8% in the placebo (p = < 0.05), and a median progression free survival (PFS) of 13.6 vs. 7.6 months (Hreshchyshyn et al., 1979). However, myelosuppression was more common in the HU group, with seven grade III or IV myelotoxicities. Another large study was conducted at the same time by Piver et al. They recruited 148 women with FIGO IIB or IIIB cervical carcinoma and again compared HU to placebo in the setting of conventional radiotherapy, with HU given every 3 days for 12 weeks. Of the stage IIB patients, 74% receiving HU had no evidence of disease at the completion of therapy compared with 43.5% of the placebo (p = < 0.01). Of the stage IIIB patients, the CR rates were 52.5 vs. 33% (p = 0.22; Piver et al., 1977). Again, 78% of patients in the HU group developed leucopenia vs. 11% in the placebo group indicating a significant toxicity in addition to the improved clinical effect. At the time these studies were published, it was felt that HU added significant benefit to the treatment of locally advanced cervical carcinoma, and HU plus radiotherapy became the standard of care for the GOG. However, over time, much of the data in these studies has been challenged, particularly in a systematic review by Symonds et al. They found a number of methodological problems with the studies such as small sample size, large numbers of exclusions post randomization, subgroup analyses of already small groups and questionable censoring. They concluded that HU “appears to add to acute toxicity and probably increases late complications” and that “there is no convincing evidence of sufficient quality to suggest a therapeutic effect of this drug” (Symonds et al., 2004).

Although the GOG initially used HU as its standard of care in the treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer, it wasn’t long before this combination was supplanted by a new adjunct to radiation therapy. One of the most important studies prompting this paradigm shift was the GOG 120 trial, first reported in 1999 (Rose et al., 1999) and recently updated (Rose et al., 2007). GOG 120 was a randomized phase III study comparing cisplatin alone vs. cisplatin, fluorouracil, and HU vs. HU alone, in conjunction with pelvic irradiation for patients with locally advanced cervical cancer and pathologically negative para-aortic nodes. They reported a significant improvement in PFS and overall survival (OS) in both cisplatin containing arms (p < 0.001), with relative risks for progression of disease or death of 0.57 and 0.51 for cisplatin alone and cisplatin, fluorouracil and HU, respectively, when compared with HU alone. In addition, toxicities were similar in all groups. Further, a similar study by Whitney et al. compared the efficacy of standard radiotherapy (RT) plus HU with standard RT plus fluorouracil (5-FU) and cisplatin in a randomized controlled trial. In 368 women with FIGO stage IIB, III, or IVA cancer of the uterine cervix, there were significant improvements in PFS and OS with the 5-FU and cisplatin combination (Whitney et al., 1999). Adverse effects included leucopenia: 4% of 5-FU/cisplatin patients and 24% of HU patients experienced grade III or IV toxicity. Given the findings of these studies, concurrent cisplatin and radiotherapy became the standard of care in locally advanced cervical cancer, spelling the end of HU use in the treatment of cervical cancer.

In addition to its study in cervical carcinoma, HU has also been extensively investigated in other cancers, particularly head and neck. While early studies had significant flaws in methodology, a phase I study showed a 90% response rate in patients treated with HU, 5-FU, and palliative dose fractionated IR (Vokes et al., 1989), prompting a series of trials by the same group and others. This included work by Mantz et al., who examined the benefit of HU when added to a more extensive chemoradiation protocol including cisplatin, 5-FU, leucovorin, and interferon-α2b induction chemotherapy followed by 5-FU and HU with fractionated radiotherapy in 32 laryngeal cancer patients. HU was dosed daily, 1 week on, 1 week off. Median follow up was 44.5 months, and, after completion of all therapy, the CR rate was 94%. Median OS was 44.5 months, and median PFS was 86, 78, and 78% at 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively, which compared favorably with other published data and for the first time saw patients with stage IV head and neck cancer failing distantly more often than locally (Mantz et al., 2001). The increased local control, unfortunately, was associated with increased toxicity, which has also been seen in other studies. One phase I study with prolonged infusion of HU with hyperfractionated, accelerated, external radiation in patients with advanced squamous cell cancer of the head and neck showed an increase in the severity of swallowing toxicity compared with previous trials, with severe edema, and reductions in motility and mobility of pharyngeal and laryngeal structures (Beitler et al., 1998). The same group later published a study examining the long term impact on swallowing that showed persistent, severe swallowing dysfunction (Smith et al., 2000). Interestingly, these studies examined continuous HU infusions based on pre-clinical data that suggested that HU should always be given concurrently with IR to maximize effect. Even though local control was excellent, with just 4 of 26 patients experiencing recurrence, quality of life is of great importance in these patients, and the late follow up reported esophageal strictures for the first time after chemoradiotherapy, suggesting that this particular regimen may be too aggressive. The state of HU in head and neck cancer is well reviewed by Argiris et al. (2003) and while the authors are optimistic about the future of chemoradiation in head and neck cancer, it remains to be seen where HU and other RR inhibitors will fit in the future treatment of this disease site.

Even as HU has slowly progressed in the clinic, work has continued on examining the mechanism by which it sensitizes cells to the effects of IR. In particular, work by Kuo et al. has shown that the sequence with which cells are treated with HU plays an important role. They demonstrated that in the Caski cervical cancer cell line, clinically relevant concentrations of HU had a significant interaction with IR, with post-IR exposure > pre-IR (Kuo et al., 1997). This was associated with increased G2 delay, suggesting a decrease in the repair of damaged DNA. In addition, in cells overexpressing the R2 subunit, HU is able to return IR sensitivity to baseline (Kuo et al., 2003), demonstrating that R2 inhibition is the likely mechanism for HU radiosensitization in these cells. These findings are potentially informative about the failure of HU to become established as a radiosensitizer in cervical cancer. In the majority of the early trials, HU was dosed once every 3 days to avoid dose limiting toxicity. Given that HU works best in vitro when dosed immediately after IR exposure, one could conclude that these trials were not optimized for best effect. In addition, HU has recently been shown to have a significant effect on the mechanism of DNA DSB repair employed by cells after exposure to IR. Burkhalter et al. showed that cells pre-incubated with HU were unable to use homologous recombination (HR) to repair DSB, and instead relied on non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). In addition, cells that were NHEJ deficient had significantly more DSB after HU treatment (Burkhalter et al., 2009). Given that NHEJ is thought to be the dominant DSB repair mechanism in cells treated with HU, RR inhibitors are likely to have enhanced activity in tumors that are NHEJ deficient.

Even with new studies on its mechanism of action, HU will likely remain consigned to history due to the many inadequacies it has as a drug molecule. While its oral absorption is almost complete and it is completely distributed in the water compartments of the body, HU has a short half-life (between 1.6 and 4.45 h; Gwilt and Tracewell, 1998) and its effectiveness is limited by relatively low affinity for RR and by the development of resistance. One area where it could potentially find use in the future is in CNS neoplasms, as it does cross the blood–brain barrier. Recent studies have examined its use in progressive meningioma in combination with 3D-conformal radiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy. In one trial, PFS at 1 and 2 years was 84 and 77%, which is similar to other adjuvant studies (Hahn et al., 2005) and randomized trials are planned.

Triapine

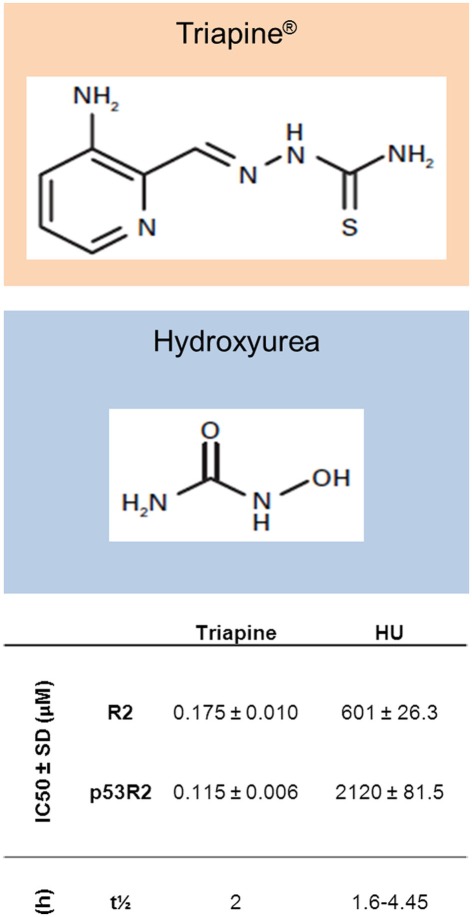

In spite of the mixed clinical data for HU, there is sufficient proof of concept to suggest that a RR inhibitor can be efficacious as a radiosensitizer in human cancers. Thus, there has been a concerted effort to discover more potent molecules with more favorable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics for this purpose. One of the more promising of these is Triapine™, a thiosemicarbazone that destroys the tyrosyl radical in R2/p53R2 by forming a redox active complex with iron, producing reactive oxygen species. In studies comparing it with HU in vitro, triapine was shown to have significantly higher potency in both enzyme and cell assays. In addition, it was fully active against HU and gemcitabine resistant cells and was equally potent against R2 and p53R2, whereas HU was approximately threefold less potent at binding p53R2 (Zhu et al., 2009). In addition, in in vivo models, triapine was active against HU resistant L1210 and KB cell lines and caused significant inhibition of solid tumor growth in mouse xenograft models (Finch et al., 2000; Figure 2). Further studies have examined the radiosensitizing properties of triapine in a number of human cell lines. Barker et al. used a panel of three human tumor cell lines, including glioma, pancreatic, and prostate cancer cells, with triapine enhancing radiosensitivity when delivered 16 h before or immediately after IR by 1.5- to 2-fold. This triapine–IR interaction was associated with a reduction in the repair of DNA DSB as evidenced by a persistence of γH2AX foci at 24 h (Barker et al., 2006). A similar effect was seen in mouse tumor xenografts, again, with greater effect if triapine was dosed just after IR. The most effective temporal relationship between triapine dosing and IR is similar to that seen with HU in earlier pre-clinical studies. Interestingly, normal human fibroblasts were only sensitized when triapine was given before, not after IR, suggesting a potential for an improved therapeutic index for IR–triapine sequencing that may be incorporated into future clinical studies.

Figure 2.

Structures of Triapine® and hydroxyurea, with in vitro and pharmacokinetic data. Shown are IC50 (concentration of compounds producing 50% inhibition of recombinant RR activity) values for both compounds in an in vitro RR activity assay with R2 or p53R2 bound to R1 (Zhu et al., 2009). Also shown are elimination half-lives (t1/2) for both compounds (Gwilt and Tracewell, 1998; Kunos et al., 2010b).

Of note, many cancers have virally or mutationally silenced p53 that allows RR activity to continue unchecked. In these cancers, it is potentially of increased importance to inhibit the R2 and p53R2 subunits that have lost p53 regulatory control. This is the case in cervical cancer, where the vast majority have dysfunctional p53 due to HPV infection. In one study, three cervical cancer cell lines with mutated or dysfunctional p53 were irradiated 6 h after triapine exposure. In all cases, the cell lines were sensitized to IR and sustained DNA damage as measured by persistence of γH2AX foci. In addition, by measuring dCTP levels, the investigators were able to show reduced RR activity in cells with and without functional p53, demonstrating that the inhibition of RR is p53 independent (Kunos et al., 2009). These findings were reinforced by further work of the same group that also showed a synergistic effect when cisplatin was added in addition to triapine and IR (Kunos et al., 2010a).

These promising pre-clinical data have prompted the initiation of a number of clinical trials. Indeed, triapine has so far been studied in 27 clinical trials in the USA at various stages of recruitment (www.clinicaltrials.gov), including those in both solid and hematologic malignancies. In particular there are three trials investigating the radiosensitizing potential of triapine, with data from one phase I study being published by Kunos et al. The purpose of their study was to assess the safety/tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and clinical activity of triapine three times weekly in concert with once weekly cisplatin and pelvic radiation in 11 patients with gynecologic malignancies. Triapine was dosed in 2 h infusions and the half-life was found to be ∼2 h. All 10 patients with advanced stage IB to IVB cervical cancer achieved complete clinical response, with a median 18 month follow up showing no disease progression in any of the patients. 6/10 had an “early” response (before brachytherapy) and 4/10 had a “late” response (after all treatments were delivered). Five of the 10 patients had PET/CT evident pelvic or para-aortic lymphadenopathy before treatment, with complete resolution on follow up imaging after treatment (Kunos et al., 2010b). 36% of patients experienced toxicity, with 78% being grade III or less. One patient had significant dyspnea and methemoglobinemia. In addition to the clinical data, the authors also examined objective markers of disease response. Late responders had a significantly higher RR activity on day 10 vs. day 1 and there was no temporal change in RR activity in the early responders, indicating that the expected spike in RR activity after IR was suppressed by triapine. The fact that the late responders experienced durable responses in spite of elevated RR activity at day 10 suggests that there may be other mechanisms of triapine activity that require further study. The promising results from this phase I trial prompted a phase II trial which is now underway.

Conclusion

Over the last 10 years, there have been a number of major leaps forward in the field of radiation oncology that allow us to deliver higher doses of radiation in ever more specific ways to our patients. Still, in the vast majority of cases, we are constrained by dose limiting toxicities that must be accounted for when designing treatment plans and balanced against the therapeutic benefit realized. Therefore, the field of radio modulation and specifically radiosensitization will continue to grow in importance in the coming years as we search for ways to maximize the therapeutic index of our treatments. While there are many different radiosensitizers currently being studied, the RR inhibitors are among the oldest of targets, and are getting a new lease of life in recent times with the development of more modern drug molecules.

As outlined in the review above, the story began with the study of HU in combination with IR in a number of pre-clinical trials in the 1960s, leading to a large amount of interest in the clinic, culminating with the GOG adopting HU and IR as its standard of care in locally advanced cervical cancer. While its success in this arena was short lived, many parallel studies investigating the mechanism of action of HU were carried out, resulting in a far clearer understanding of the biological interactions between IR and RR inhibitors. Even as HU was fading from view, investigators were working on successors including the intriguing molecule, triapine. As shown above, this drug works in a similar fashion to HU, but has significantly improved potency, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics. The phase I study in cervical cancers that was recently published includes some very encouraging data, and the field waits in anticipation for the publication of further trials. It remains to be seen what the best dosing regimen for triapine will be, however the weight of pre-clinical data, including that with HU, suggests that daily dosing shortly after radiation therapy will be most effective and provide the greatest therapeutic window. These authors would encourage studies incorporating this type of dosing schedule in the clinic, although this must obviously be weighed carefully against the potential for increased toxicity.

In addition to triapine, there are other new RR inhibitors being tested at various stages, including trimidox and motexafin gadolinium. Trimidox (3,4,5-trihydroxybenzamidoxime) was first described by Szekeres et al. (1994), in a paper that reported ∼100-fold more potency at RR than HU in a cell based assay. Subsequent in vitro studies have demonstrated that while it acts as a radiosensitizer in Panc-1 human pancreatic cancer cells (Ahmed and Hassan, 2000), it is less potent than HU and further work is ongoing to fully assess its potential. Motexafin gadolinium is a texaphyrin molecule that targets thioredoxin reductase in addition to RR. In in vitro experiments, it was shown to inhibit RR with an IC50 of 2–6 μM (Hashemy et al., 2006), although given that it has a number of other cellular effects, it is unclear how much of its potency as a radiosensitizer is due to RR inhibition alone. It is likely that the coming years will continue to see the emergence of new RR inhibitors with unique properties.

The recent advances in the understanding of RR biology and the development of new inhibitors places us at an important crossroads in the story of RR inhibitors. There are sufficient data to provide proof of concept for the target from a biological standpoint, however clinical trials to this point have not been wholly convincing. It will be interesting to follow the development of the field in the next 5–10 years, particularly with the clinical trials of triapine in cervical cancer, and hopefully at least one of the many RR inhibitors being studied will eventually bring additional therapeutic benefit to patients in the near future.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmed D., Hassan H. (2000). Hydroxyurea and trimidox enhance the radiation effect in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Anticancer Res. 20, 133–138 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argiris A., Haraf D., Kies M., Vokes E. (2003). Intensive concurrent chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancer with 5-fluorouracil- and hydroxyurea-based regimens: reversing a pattern of failure. Oncologist 8, 350–360 10.1634/theoncologist.8-4-350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker C., Burgan W., Carter D., Cerna D., Gius D., Hollingshead M., Camphausen K., Tofilon P. (2006). In vitro and in vivo radiosensitization induced by the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor triapine (3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde-thiosemicarbazone). Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 2912–2918 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitler J., Smith R., Haynes H., Silver C., Quish A., Kotz T., Serrano M., Brook A., Wadler S. (1998). A phase I clinical trial of prolonged infusion of hydroxyurea in combination with hyperfractionated, accelerated, external radiation therapy in patients with advanced squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Invest. New Drugs 16, 161–169 10.1023/A:1006102716920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhalter M., Roberts S., Havener J., Ramsden D. (2009). Activity of ribonucleotide reductase helps determine how cells repair DNA double strand breaks. DNA Repair (Amst.) 8, 1258–1263 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabes A., Thelander L. (2000). Controlled protein degradation regulates ribonucleotide reductase activity in proliferating mammalian cells during the normal cell cycle and in response to DNA damage and replication blocks. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 17747–17753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filatov D., Bjorklund S., Johansson E., Thelander L. (1996). Induction of the mouse ribonucleotide reductase R1 and R2 genes in response to DNA damage by UV light. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 23698–23704 10.1074/jbc.271.39.23698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch R., Liu M., Grill S., Rose W., Loomis R., Vazquez K., Cheng Y., Sartorelli A. (2000). Triapine (3-aminopyridine-2-carboxyaldehyde-thisemicarbazone): a potent inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase activity with broad spectrum antitumor activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 59, 983–991 10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00419-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gojo I., Tidwell M., Greer J., Takebe N., Seiter K., Pochron M., Johnson B., Sznol M., Karp J. (2007). Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of Triapine®, a potent ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor, in adults with advanced hematologic malignancies. Leuk. Res. 31, 1165–1173 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitett O., Hakansson P., Voevodskaya N., Fridd S., Graslund A., Arakawa H., Nakamura Y., Thelander L. (2001). Mammalian p53R2 protein forms an active ribonucleotide reductase in vitro with R1 protein, which is expressed both in resting cells in response to DNA damage and in proliferating cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 40647–40651 10.1074/jbc.M106088200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwilt P., Tracewell W. (1998). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of hydroxyurea. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 34, 347–358 10.2165/00003088-199834050-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn B., Schrell U., Sauer R., Fahlbusch R., Ganslandt O., Grabenbauer G. (2005). Prolonged oral hydroxyurea and concurrent 3-d conformal radiation in patients with progressive or recurrent meningioma: results of a pilot study. J. Neurooncol. 74, 157–165 10.1007/s11060-004-2337-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemy S., Ungerstedt J., Avval F., Holmgren A. (2006). Motexafin gadolinium, a tumor-selective drug targeting thioredoxin reductase and ribonucleotide reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 10691–10697 10.1074/jbc.M511373200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hreshchyshyn M., Aron B., Boronow R., Franklin E., Shingleton H., Blessing J. (1979). Hydroxyurea or placebo combined with radiation to treat stages IIIB and IV cervical cancer confined to the pelvis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 5, 317–322 10.1016/0360-3016(79)91209-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunos C., Chiu S., Pink J., Kinsella T. (2009). Modulating radiation resistance by inhibiting ribonucleotide reductase in cancers with virally or mutationally silenced p53 protein. Radiat. Res. 172, 666–676 10.1667/RR1858.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunos C., Radivoyevitch T., Pink J., Chiu S., Stefan T., Jacobberger J., Kinsella T. (2010a). Ribonucleotide reductase inhibition enhances chemoradiosensitivity of human cervical cancers. Radiat. Res. 174, 574–581 10.1667/RR2273.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunos C., Waggoner S., von Greunigen V., Eldermire E., Pink J., Dowlati A., Kinsella T. (2010b). Phase I trial of pelvic radiation, weekly cisplatin, and 3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone (3-AP, NSC #663249) for locally advanced cervical cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 1298–1306 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M., Hwang H., Sosnay P., Kunugi K., Kinsella T. (2003). Overexpression of the R2 subunit of ribonucleotide reductase in human nasopharyngeal cells reduces radiosensitivity. Cancer J. Sci. Am. 9, 277–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M., Kinsella T. (1998). Expression of ribonucleotide reductase after ionizing radiation in human cervical carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 58, 2245–2252 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M., Kunugi K., Lindstrom M., Kinsella T. (1997). The interaction of hydroxyurea and ionizing radiation in human cervical carcinoma cells. Cancer J. Sci. Am. 3, 163–173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantz C., Vokes E., Kies M., Mittal B., Witt M., List M., Weichselbaum R., Haraf D. (2001). Sequential induction chemotherapy and concomitant chemoradiotherapy in the management of locoregionally advanced laryngeal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 12, 343–347 10.1023/A:1011188726802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piver M., Barlow J., Vongtama V., Blumenson L. (1977). Hydroxyurea as a radiation sensitizer in women with carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 129, 379–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piver M., Howes A., Suit H., Marshall N. (1972). Effect of hydroxyurea on the radiation response of C3H mouse mammary tumors. Cancer 29, 407–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose P., Ali S., Watkins E., Thigpen J., Deppe G., Clarke-Pearson D., Insalaco S. (2007). Long-term follow-up of a randomized trial comparing concurrent single agent cisplatin, cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy, or hydroxyurea during pelvic irradiation for locally advanced cervical cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 2804–2810 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.4532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose P., Bundy B., Watkins E., Thigpen J., Deppe G., Maiman M., Clarke-Pearson D., Insalaco S. (1999). Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 340, 1144–1153 10.1056/NEJM199904153401502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair W. (1968). The combined effect of hydroxyurea and x-rays on Chinese hamster ovary cells in vitro. Cancer Res. 28, 198–206 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R., Kotz T., Beitler J., Wadler S. (2000). Long-term swallowing problems after organ preservation therapy with concomitant radiation therapy and intravenous hydroxyurea. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 126, 384–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stearns B., Losee K., Bernstein J. (1963). Hydroxyurea. A new type of potential antitumor agent. J. Med. Chem. 6, 201. 10.1021/jm00338a026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symonds R., Collingwood M., Kirwan J., Humber C., Tierney J., Green J., Williams C. (2004). Concomitant hydroxyurea plus radiotherapy versus radiotherapy for carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a systematic review. Cancer Treat. Rev. 30, 405–414 10.1016/j.ctrv.2003.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekeres T., Gharehbaghi K., Fritzer M., Woody M., Srivastava A., Riet B., Jayaram H., Elford H. (1994). Biochemical and antitumor activity of trimidox, a new inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 34, 63–66 10.1007/BF00686113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H., Arakawa H., Yamaguchi T., Shiraishi K., Fukuda S., Matsui K., Takei Y., Nakamura Y. (2000). A ribonucleotide reductase gene involved in a p53-dependent cell-cycle checkpoint for DNA damage. Nature 404, 42–49 10.1038/35003506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsimberidou A., Alvarado Y., Giles F. (2002). Evolving role of ribonucleoside reductase inhibitors in hematologic malignancies. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2, 437–448 10.1586/14737140.2.4.437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vokes E., Panje W., Schilsky R., Mick R., Awan A., Moran W., Goldman M., Tybor A., Weichselbaum R. (1989). Hydroxyurea, fluorouracil, and concomitant radiotherapy in poor prognosis head and neck cancer: a phase I-II study. J. Clin. Oncol. 7, 761–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney C., Sause W., Bundy B., Malfetano J., Hannigan E., Fowler W., Clarke-Pearson D., Liao S. (1999). Randomized comparison of fluorouracil plus cisplatin versus hydroxyurea as an adjunct to radiation therapy in stage IIB-IVA carcinoma of the cervix with negative para-aortic lymph nodes: a Gynecologic Oncology Group and Southwest Oncology Group Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 17, 1339–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L., Zhou B., Liu X., Qiu W., Jin Z., Yen Y. (2003). Wild-type p53 regulates human ribonucleotide reductase by protein-protein interaction with p53R2 as well as hRRM2 subunits. Cancer Res. 63, 980–986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T., Matsuda K., Sagiya Y., Iwadate M., Fujino M., Nakamura Y., Arakawa H. (2001). p53R2-dependent pathway for DNA synthesis in a p53-regulated cell cycle checkpoint. Cancer Res. 61, 8256–8262 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Zhou B., Chen X., Jiang H., Shao J., Yen Y. (2009). Inhibitory mechanisms of heterocyclic carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazones for two forms of human ribonucleotide reductase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 78, 1178–1185 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.06.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]