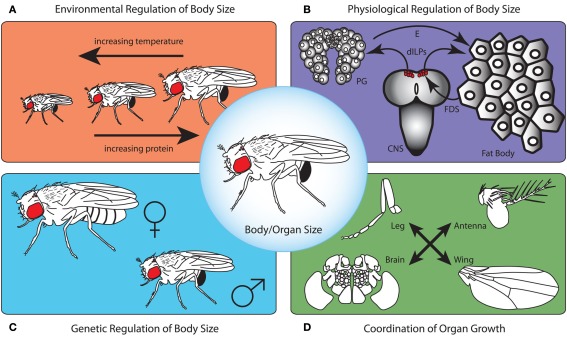

Figure 1.

To produce a correctly proportioned animal whose physiology and size is appropriate for the environmental conditions in which it was reared, body size needs to be regulated on several levels. First, the environment controls developmental processes that determine final body size (A). As temperature increases, body size tends to decrease. Furthermore, as protein content in the larval food increases, adult size increases. This is due to the action of environmentally regulated signaling cascades on mechanisms that regulate growth rate and developmental timing (B). The fat body senses nutritional conditions and communicates this to the central nervous system (CNS) via a fat body derived signal (FDS). This FDS acts on the insulin producing neurosecretory cells to regulate the production of Drosophila insulin-like peptides (dILPs). dILPs, in turn regulate growth rate and the production of the steroid molting hormone ecdysone (E) by the prothoracic gland cells thereby determining the duration of the growth period. For any given environmental condition, the genetic background contributes to overall body size (C). For example, independent of rearing conditions, males are typically smaller than females. Lastly, in addition to this physiological regulation of whole body size, the size of individual organs is controlled by mechanisms that regulate organ-autonomous growth and those that ensure organs grow in proportion to one another (D).