To the Editor: Rickettsiae are vector-borne pathogens that affect humans and animals worldwide (1). Pathogens in the Rickettsia conorii complex are known to cause Mediterranean spotted fever (MSF) (R. conorii Malish strain), Astrakhan fever (R. conorii Astrakhan strain), Israeli spotted fever (R. conorii Israeli spotted fever strain), and Indian tick typhus (R. conorii Indian tick typhus strain) in the Mediterranean basin and Africa, southern Russia, the Middle East, and India and Pakistan, respectively (2). These rickettsioses share some clinical features, such as febrile illness and generalized cutaneous rash, and are transmitted to humans by Rhipicephalus spp. ticks (2).

MSF is endemic to Sicily (Italy); fatal cases occur each year, and the prevalence of R. conorii in dogs is high (3–6). Recently, R. conorii Malish strain and R. conorii Israeli spotted fever strain were confirmed in humans in Sicily in whom MSF was diagnosed (4), which suggests that other R. conorii strains might be present and diagnosed as causing MSF. The rickettsiae within the R. conorii complex, which are relevant for the study of bacterial evolution and epidemiology, can be properly identified only by appropriate genetic analyses.

We analyzed 15 blood and 19 inoculation eschar samples collected during 2005–2009 from 31 patients in Palermo Province and 2 in Catania Province, none of whom had recently traveled. None were severely ill, but all 33 had clinical manifestations and laboratory results compatible with MSF: 1-week incubation after tick bite, fever, headache, myalgia, papulonodular rash that started on the upper limbs and spread centripetally with or without tache noire, and detection of antibody titers >180 to R. conorii by indirect immunofluorescence antibody test (bioMérieux, Marcy L’Etoile, France).

Total DNA was extracted by using the GeneElute Mammalian Genomic DNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy) and used to analyze Rickettsia spp. sequences by PCR, cloning, and sequence analysis of the amplicons. At least 3 clones were sequenced for each amplicon. Genes targeted by PCR included ATP synthase α subunit (atpA) (7), heat-shock protein 70 (dnaK) (7), outer membrane protein A (ompA) (primers Rr190.70p and 190–701 [8]), outer membrane protein B (ompB) (primers rompBSFGIF and rompBSFG/TGIR [9]), citrate synthase (gltA) (2), and 17-kDa protein (primers TZ15–19 and TZ16–20 [6]). Nucleotide sequence identity to reference strains (2), multilocus analysis by atpA–dnaK–ompA–ompB–gltA–17-kDa and ompA–ompB sequences and in silico PstI-RsaI restriction analysis of ompA sequences (8) were used to characterize Rickettsia spp. and R. conorii strains.

Results for 15 (45%) patients were positive for Rickettsia spp. Thirteen isolates were confirmed as R. conorii Malish strain (identification [ID] nos. 44, 45, 47, 49, 54, 55, 57, 59, 61, 66, 68, 92, 112) and 1 each as R. conorii Indian tick typhus strain (ID no. 58) and R. slovaca (ID no. 50). R. slovaca DNA was also found in a Dermacentor marginatus tick removed from the patient who had confirmed R. slovaca infection. R. conorii Malish strains showed 99.9%–100%, 100%, 100%, 98.7%–100%, 100%, and 97.8%–100% pairwise nt sequence identity to reference strain Malish 7 (AE006914) atpA, dnaK, ompA, ompB, gltA, and 17-kDa protein, respectively.

The R. conorii Indian tick typhus strain showed 100%, 100%, 99.4%, 100%, 100%, and 99.9% pairwise nt sequence identity to R. conorii strain Malish 7 (AE006914) atpA, dnaK, 17-kDa protein, and R. conorii Indian tick typhus reference strain ompA (U43794), ompB (AF123726), and gltA (U59730), respectively. The R. slovaca strain showed 99.4%, 97.8%, 100%, 93.7%, 99.7%, and 99.4% pairwise nt sequence identity to R. slovaca atpA (AY124734), dnaK (DQ821824), ompA (HM149286), ompB (HQ232242), gltA (AY129301), and R. conorii strain Malish 7 (AE006914) 17-kDa protein, respectively. The sequences were deposited in GeneBank under accession nos. JN182782–JN182804.

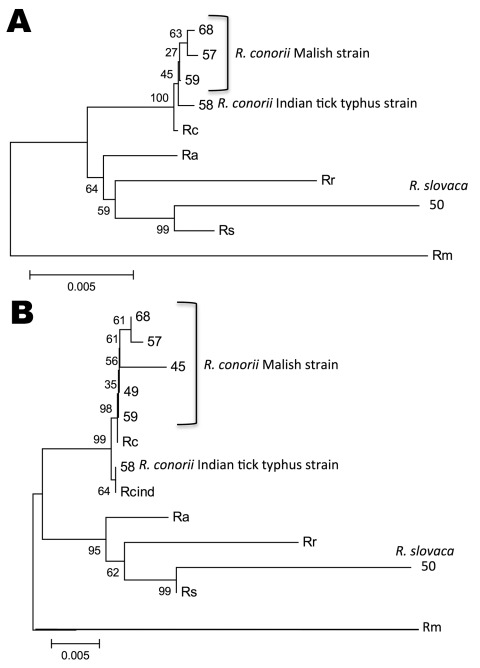

Multilocus sequence analysis (Figure, panel A) and in silico PstI-RsaI restriction analysis of ompA sequences also confirmed the identity of the Rickettsia spp. we identified. As shown (2), multilocus analysis with ompA–ompB sequences was highly informative about the phylogenetic relationship between Rickettsia spp. and R. conorii strains (Figure, panel B).

Figure.

Multilocus sequence analysis of Rickettsia spp. Evolutionary history was inferred by using the neighbor-joining method for ATP synthase α subunit (atpA)–heat shock protein 70 (dnaK)–outer membrane protein A (ompA)–ompB–citrate synthase (gltA)–17-kDa (A) and ompA–ompB sequences (B). The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 0.06205323 (A) and 0.11097561 (B) is shown. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) are shown next to the branches. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic relationship. Evolutionary distances were computed by using the Kimura 2-parameter method and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. All ambiguous positions were removed for each sequence pair. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA5 (www.megasoftware.net). Identification numbers of strains detected are shown with the species/strain name next to them. Rc, R. conorii strain Malish 7; Ra, R. africae strain ESF-5; Rr, R. rickettsii strain Iowa; Rs, R. slovaca; Rm, R. massiliae strain MTU5; Rcind, R. conorii Indian tick typhus strain.

In Sicily, R. conorii Malish strain has been characterized in MSF patients (4), and R. slovaca DNA was identified in ixodid ticks (5). However, to our knowledge, R. slovaca in humans in Sicily and R. conorii Indian tick typhus strain infection in Sicily and Europe have not been reported. The only previous report outside India and Pakistan was documented in a traveler with severe clinical manifestations in France (10). Differences were not observed between R. conorii Indian tick typhus strain and R. slovaca–infected patients. Both patients had similar clinical symptoms compatible with MSF; in both, only IgM for rickettsiae was detected at hospital admission, but IgM and IgG were detected during convalescence. Tache noire were detected in the neck and right arm of patients with R. conorii Indian tick typhus strain and R. slovaca, respectively.

These results demonstrated that new rickettsiae, such as R. conorii Indian tick typhus strain, of public health relevance are emerging in Europe. The widespread distribution of tick vectors in Europe and the transtadial and transovarial transmission of the pathogen in ticks might favor transmission to humans.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health, project IZSSI 08/08.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Torina A, Fernández de Mera IG, Alongi A, Mangold AJ, Blanda V, Scarlata F, et al. Rickettsia conorii Indian tick typhus strain and R. slovaca in humans, Sicily [letter]. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet] 2012 Jun [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1806.110966

References

- 1.Nicholson WL, Allen KE, McQuiston JH, Breitschwerdt EB, Little SE. The increasing recognition of rickettsial pathogens in dogs and people. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:205–12. 10.1016/j.pt.2010.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu Y, Fournier PE, Eremeeva M, Raoult D. Proposal to create subspecies of Rickettsia conorii based on multi-locus sequence typing and an emended description of Rickettsia conorii. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:11. 10.1186/1471-2180-5-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciceroni L, Pinto A, Ciarrocchi S, Ciervo A. Current knowledge of rickettsial diseases in Italy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1078:143–9. 10.1196/annals.1374.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giammanco GM, Vitale G, Mansueto S, Capra G, Caleca MP, Ammatuna P. Presence of Rickettsia conorii subsp. israelensis, the causative agent of Israeli spotted fever, in Sicily, Italy, ascertained in a retrospective study. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:6027–31. 10.1128/JCM.43.12.6027-6031.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beninati T, Genchi C, Torina A, Caracappa S, Bandi C, Lo N. Rickettsiae in ixodid ticks, Sicily. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:509–11. 10.3201/eid1103.040812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tzianabos T, Anderson BE, McDade JE. Detection of Rickettsia rickettsii DNA in clinical specimens by using polymerase chain reaction technology. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2866–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernández de Mera IG, Zivkovic Z, Bolaños M, Carranza C, Pérez-Arellano JL, Gutiérrez C, et al. Rickettsia massiliae in the Canary Islands. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1869–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roux V, Fournier PE, Raoult D. Differentiation of spotted fever group rickettsiae by sequencing and analysis of restriction fragment length polymorphism of PCR-amplified DNA of the gene encoding the protein rOmpA. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2058–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi YJ, Jang WJ, Ryu JS, Lee SH, Park KH, Paik HS, et al. Spotted fever group and typhus group rickettsioses in humans, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:237–44. 10.3201/eid1102.040603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parola P, Fenollar F, Badiaga S, Brouqui P, Raoult D. First documentation of Rickettsia conorii infection (strain Indian tick typhus) in a traveler. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:909–10. 10.3201/eid0705.010527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]