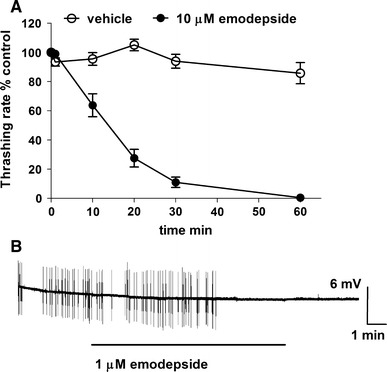

Fig. 1.

Examples of the time-course of the effect of emodepside on C. elegans motility and feeding. a The time-course of the inhibitory effect of emodepside on motility in liquid: control n = 10, emodepside n = 27, mean ± SE mean. The thrashing rate in each treatment group was measured at time 0 and then followed for a further 60 min at 10 min intervals. The thrashing rate at each time-point is expressed as a percentage of the initial thrashing rate at time 0. The vehicle was 0.1 % ethanol and the thrashing rate of this control group did not alter significantly over the time-course of the experiment (Amliwala 2005). b An example of the time-course of the effect of emodepside on pharyngeal activity in a cut head preparation. The recordings are extracellular electrophysiological recordings taken from the pharyngeal muscle. Each vertical deflection records a pharyngeal muscle contraction–relaxation cycle or pump. The bar indicates the duration of application of emodepside. Emodepside acts on SLO-1 in the pharyngeal circuit to inhibit pumping (Guest et al. 2007; Dillon et al. 2009). Note this experiment was performed in the absence of any 5-HT (which may be used to provide an excitation against which inhibition can be measured) and that in the absence of 5-HT the basal pumping rate in the cut head preparation is very slow. This recording illustrates the slow time to onset of the emodepside inhibition but the rapid manner in which pumping is turned off following this latency of onset. This can be explained by considering that at low rates of pumping, when the excitatory neuronal input to the pharynx is minimal, the inhibitory effect of emodepside is sufficient to turn pumping off completely. The data are taken from (Bull 2007)