Abstract

Amniotic fluid (AF) was described as a potential source of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for biomedicine purposes. Therefore, evaluation of alternative cryoprotectants and freezing protocols capable to maintain the viability and stemness of these cells after cooling is still needed. AF stem cells (AFSCs) were tested for different freezing methods and cryoprotectants. Cell viability, gene expression, surface markers, and plasticity were evaluated after thawing. AFSCs expressed undifferentiated genes Oct4 and Nanog; presented typical markers (CD29, CD44, CD90, and CD105) and were able to differentiate into mesenchymal lineages. All tested cryoprotectants preserved the features of AFSCs however, variations in cell viability were observed. In this concern, dimethyl sulfoxide (Me2SO) showed the best results. The freezing protocols tested did not promote significant changes in the AFSCs viability. Time programmed and nonprogrammed freezing methods could be used for successful AFSCs cryopreservation for 6 months. Although tested cryoprotectants maintained undifferentiated gene expression, typical markers, and plasticity of AFSCs, only Me2SO and glycerol presented workable viability ratios.

1. Introduction

Knowledge about cryopreservation protocols that keep unchanged original stem cells properties is extremely important for cell culture and stem cells storage. For prolonged storage, cells are usually slowly frozen and stored at −196°C in liquid nitrogen. Slowly cooling avoids intracellular ice buildup, which can cause rupture of the cell membrane. Nevertheless, it can result in dehydration of the cells by formation of extracellular ice. To prevent this, an ideal cooling rate should be chosen and a cryoprotectant added. The general properties required for the cryoprotectant compounds are that they have low molecular weight, are nontoxic, and have low costs [1, 2].

Cryoprotectants are divided into two main classes: intracellular agents, which penetrate inside the cells preventing ice crystals formation and membrane rupture (i.e., dimethyl sulfoxide (Me2SO), glycerol, and ethylene glycol) and extracellular compounds that do not penetrate in cell membrane and act by reducing the hyperosmotic effect present in freezing procedure. Among them are sucrose, trehalose, dextrose, and polyvinylpyrrolidone [3].

The main commonly used cryoprotectant, dimethylsulfoxide (Me2SO), provides a high rate of postfreezing cell survival, but several groups show that it can promote stem-cell differentiation in neuronal lineage and also presents cytotoxicity at room temperature [4–8]. There are few alternative cryoprotectants to Me2SO use at the moment. Other substances such as glycerol, sucrose, or trehalose do not present cytotoxicity but still need to be more evaluated as cryoprotectants for mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs).

MSCs are multipotent cells capable to differentiate into several lineages in vitro. They are described as adherent cells with fibroblast-like morphology and able to differentiate in mesenchymal lineages such as chondrogenic, osteogenic, myogenic, and adipogenic [9]. In other studies it was demonstrated that MSCs, under proper conditions, are also capable of differentiating into nonmesenchymal lineages as hepatocyte and neuronal-like cells [10, 11]. Human amniotic fluid (AF), a dynamic and complex mixture that reflects the physiological status of the developing fetus, was related recently as an alternative source of MSCs [12].

AF obtained in second trimester of pregnancy is composed of a wide variety of cells derived mainly from fetal exfoliation during development. Among these cells, some have adherent properties and express undifferentiated markers such as Oct-4 gene. These cells are also capable of self-renewal and differentiation into mesodermal tissues in culture. They have been classified as amniotic fluid mesenchymal stem cells (AFSCs) [13–15].

Here we evaluated the effects of two cryopreservation methods (time-programmed and nonprogrammed temperature freezing) and four distinct cryoprotectants in the AFSCs viability and main characteristics maintenance after liquid nitrogen storage.

2. Materials and Methods

All culture media and chemical reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Fetal bovine serum and antibiotics were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Primers were from IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA). Ntera-2.c1D1 (human pluripotent testicular carcinoma/ATCC CRL-1973) was purchased from American Cell Type Collection (Manassas, VA, USA).

2.1. Human Amniotic Fluid Stem Cells

Human amniotic fluid samples were collected during scheduled amniocentesis at 12 to 18 weeks of gestation for diagnosis reasons. Collection procedure was performed under aseptic conditions using a 22-gauge needle and under ultrasonographic control. All samples were obtained after signed informed consent. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee from University of Sao Paulo School of Medicine, Brazil (no.: 0410-09).

After collection, each sample was centrifuged at 450 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The resulting pellets were washed with PBS (phosphate buffer saline), suspended in minimal essential medium—α-modification (α-MEM), supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum, 100 UI/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and maintained in incubator with 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C for approximately 12 days, when the first colonies appeared. The medium was changed every 3-4 days.

2.2. Growth Curve and Doubling Time

For growth curve, AFSCs were seeded in 48-well plates (Corning, USA), and cultivated for 12 days in a platting density of 5,000 cells/cm2. Cell number was assessed daily in triplicate by trypan blue staining in hemocytometer (Optik Labor, Friedrichshofen, Germany) counting. Cell population doubling time was calculated by the following formula: t = 3,3 × log(Y/Y0), where: T: time (hours), Y: final cell number, and Y0: starting cell number.

2.3. AFSC Undifferentiated Gene Expression by RT-PCR

To evaluate undifferentiated state of AFSCs, specific gene expressions were determined: Oct-4 and Nanog. Total RNA was extracted using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purity of the RNA was assessed by determining the ratio of absorbance at 260 nm to that at 280 nm. The reactions were performed with the kit Illustra Ready To Go (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) in a PTC-200 thermal cycler (MJ Research Inc., Watertown, USA). Approximately 100 ng of total RNA were required for reactions.

RT-PCR was performed initially with a step of 50°C for 30 min for reverse transcription of RNA and denaturation at 95°C for 5 min. This was followed by 35 cycles (94°C for 30 sec, 57°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 60 sec; final extension at 72°C for 8 min). All used sense and antisense primers are described in Table 1. Total RNA from Ntera-2.c1D1 cell line was used as positive control of undifferentiating state of AFSCs. Human β-actin gene was used as endogenous control in all reactions. RT-PCR products were analyzed in 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under ultraviolet light.

Table 1.

RT-PCR primer sequences.

| Gene | Primers | PCR products (bp) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oct-4 | 5′- cgt gaa gct gga gaa gga gaa gct g -3′ 5′- caa ggg ccg cag ctt aca cat gtt c-3′ |

247 | 61 |

| Nanog | 5′-cat gag tgt gga tcc agc ttg-3′ 5′-cct gaa taa gca gat cca tgg-3′ |

191 | 52 |

| Osteocalcin | 5′-atg aga gcc ctc aca ctc ct-3′ 5′ caa ggg gaa gag gaa aga ag-3′ |

359 | 55 |

| Osteopontin | 5′-cat ggc atc acc tgt gcc ata cc-3′ 5′-cag tga cca gtt cat cag att cat c-3′ |

331 | 57 |

| Wnt-1 | 5′-cac gac act cgt gca gta cgc-3′ 5′-aca gac act cgt gca gta cgc-3′ |

233 | 58 |

| Collagen 2A1 | 5′-cca gga cca aag gga cag aaa g-3′ 5′-ttc acc agg ttc acc agg att g-3′ |

398 | 57 |

| Perlecan | 5′-cat aga gac cgt cac agc aag-3′ 5′-atg aac acc aca ctg aca acc-3′ |

300 | 55 |

| Syndecan | 5′-cct tca cac tcc cca cac-3′ 5′-ggc ata gaa ttc ctc ctg ttg-3′ |

410 | 54 |

| PPAR-γ 2 | 5′-gct gtt atg ggt gaa act ctg-3′ 5′-ata agg tgg aga tgc agg ctc-3′ |

351 | 55 |

| Lipoprotein lipase | 5′-cag caa aac ctt ca tggt-3′ 5′-agt ttt ggc acc caa ctc tca-3′ |

72 | 53 |

| β-actin | 5′-tgg cac cac acc ttc tac aat gag c-3′ 5′-gca cag ctt ctc ctt aat gtc acg c-3′ |

396 | 60 |

2.4. Flow Cytometry Analysis

Specific surface proteins of cultured AFSCs were evaluated by flow cytometry (FacsCalibur cytometer, Becton Dickinson) and analyzed in CellQuest software. 1 × 106 cells were trypsinized, washed with PBS, and stained for 15 min in dark room with primary antibodies labeled with fluorochromes FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate): CD34, CD44, CD45, and CD90; PE (phycoerythrin): CD14, CD29, CD105, and appropriate isotype controls (IgG-1, Invitrogen, Caltagaboratories, USA). The number of acquired events was 20,000 cells in each acquisition.

2.5. Cell Differentiation Assays

To induce osteogenic differentiation, AFSCs at 70–80% confluence were cultured in osteogenic medium (α-MEM supplemented with 20% FBS, 10 mM glycerol phosphate, 50 mM ascorbic acid, and 100 nM dexamethasone) for 3 weeks. The medium was changed twice weekly. The osteogenic differentiation was evaluated by cell staining (Alizarin Red and von Kossa) and RT-PCR (osteocalcin, osteopontin and Wnt-1 gene expression).

To induce adipose tissue differentiation, AFSCs were treated with adipogenic medium: α-MEM with 10−2 uM dexamethasone, 0.5 mg/mL insulin, 200 mM indomethacin and 50 mM isobutilmethilxantine for 3 weeks. Medium changes were carried out twice weekly. Presence of intracellular lipid droplets, indicative of adipocyte differentiation, was assessed by Oil Red O staining. PPAr-γ and lipoprotein lipase gene expression was determined by RT-PCR.

To induce chondrogenic differentiation, AFSCs were grown in α-MEM until 80% of confluence was reached. Cells were trypsinized, transferred to a conical tube, and centrifuged at 450x g for 10 min at room temperature. Chondrogenesis was induced by treating pelleted cells in conical tubes with α-MEM medium, 10 ng/mL TGF-βI (Calbiochem, USA) and 100 nM dexamethasone for 3 weeks. Chondrogenic differentiation was assessed by hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E), immunofluorescence against collagen type II and RT-PCR (collagen II, perlecan, and syndecan gene expression).

2.6. Cryopreservation

AFSCs (third passage) were frozen in the final concentration of 106 cells/mL in freezing medium (α-MEM 20% FBS plus cryoprotectant), by two different methods. In the nonprogrammed time freezing protocol, samples were placed in a freezer (−20°C) for 20 min followed by −80°C freezing for 12–16 h and, finally, transferred into liquid nitrogen (N2). Alternatively, programmed time freezing protocol was used where samples were cooled in a controlled-rate program (Thermo Forma Scientific, Minneapolis, USA) of 1°C/min at −60°C, then 3°C/min at −100°C followed by liquid N2 storage. The cryoprotectants used alone were Me2SO (5 and 10%), glycerol (5 and 10%), sucrose (30 and 60 mM), and trehalose (60 and 100 mM). The samples were stored for 3 and 6 months. Thawing was done quickly in water bath at 37°C, and then cell viability was analyzed. Before cell plating all samples were washed with α-MEM medium to remove residual cryoprotectant. After 80% cell confluence was reached, Oct-4 and Nanog expression was evaluated by RT-PCR; CD34, CD45, CD44 (FITC), CD14, CD29 and CD105 (PE) membrane markers were measured by flow cytometry; osteogenic and adipogenic differentiations were performed and confirmed by Alizarin Red and Oil Red O staining, respectively.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. One-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to the means to determine statistical differences between experimental groups followed by Bonferroni or Dunnett's tests. Differences between mean values were considered significant when P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. AFSCs Isolation and Doubling Time

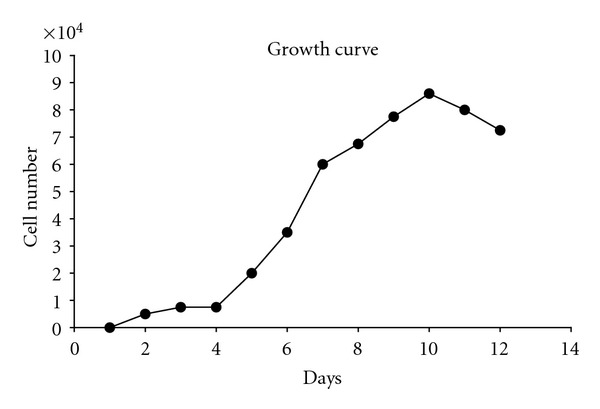

AFSCs were isolated of 35 of 41 samples by their adherent properties in plastic surface and appeared as colonies in the culture flask. They consisted of fibroblast-like cell morphology. Doubling time for AFSCs calculated after growth curve was 30 ± 4 h (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

AFSCs growth curve and doubling time. AFSCs (5,000 cells/cm2) were seeded and cultivated in 46-well plates for 12 days. At the end of each day, cells were washed, trypsinizated, and counted in hemocytometer. Each point refers to triplicate from two different AF samples. Cell doubling time calculated was 30 hours (±4 h).

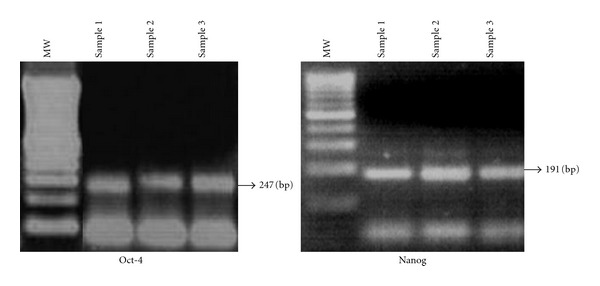

3.2. Cultured AFSCs Express Oct-4 and Nanog

Cultured AFSCs expressed the transcription factors Oct-4 at different passages, as determined by RT-PCR. Oct-4 is a key marker expressed in embryonic stem cells and cancer cells and is responsible for the maintenance of the undifferentiated state. The homeodomain gene Nanog, present in pluripotent human cells, was also expressed in cultured AFSCs confirming the undifferentiated state (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Undifferentiated gene expression (Oct-4 and Nanog). AFSCs total RNA was extracted from 3 different samples by Trizol method, gene expression evaluated by RT-PCR, and electrophoresed and visualized under ultraviolet light in 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

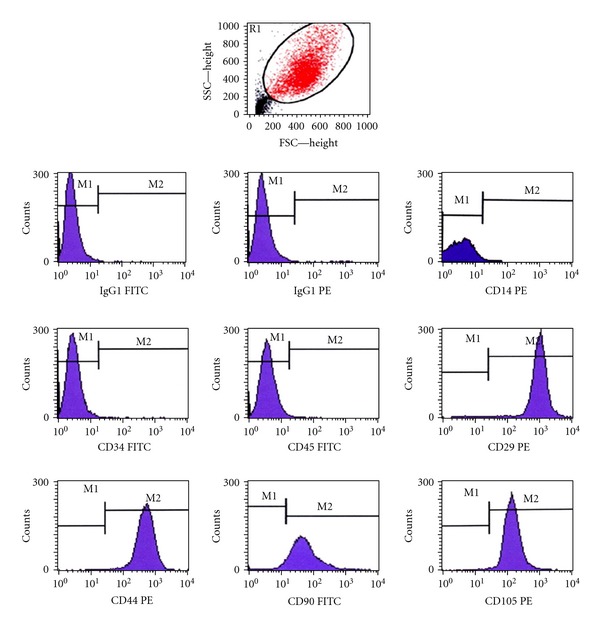

3.3. Phenotypic Characterization of AFSCs by Flow Cytometry

The results obtained by flow cytometry demonstrated that stem cells isolated from amniotic fluid have a strong positivity for mesenchymal markers, such as CD29 (β-integrin), CD44 (hyaluronic acid receptor), CD90 (Thy-1), and CD105 (endoglin), while they were negative for hematopoietic markers such as CD14, CD34 and CD45 (leukocyte common antigen) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

AFSCs membrane proteins were evaluated by flow cytometry with CellQuest software. Acquisitions were shown in histograms. AFSCs were positive for CD29 (98.27 ± 1.23%), CD44 (98.28 ± 1.65%), CD90 (97.69 ± 1.84%), CD105 (98.77 ± 0.64%) and were negative for CD14 (1.78 ± 1.06%), CD34 (1.70 ± 1.14%), and CD45 (1.80 ± 0.74%). IgG1-FITC and IgG1-PE antibodies were utilized as isotype controls. The number of acquired events was 20,000 in each acquisition.

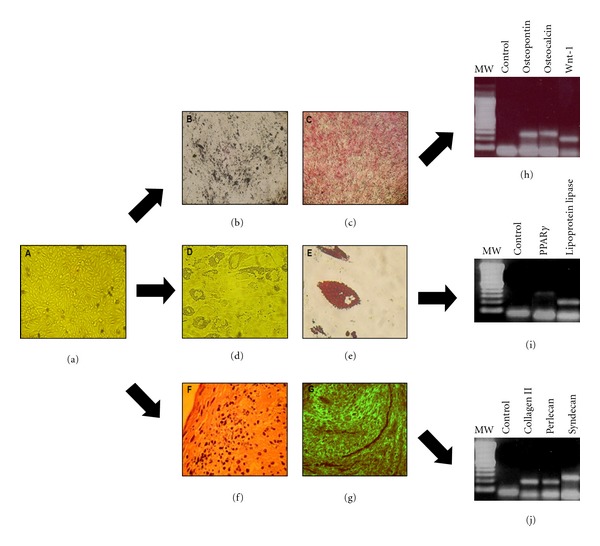

3.4. Differentiation Properties of AFSCs

AFSCs were cultivated in specific differentiation medium, as described, to evaluate their plasticity and multipotency. Osteogenic differentiation was confirmed after 21 days by visualization of the calcium deposits seen with Alizarin Red and von Kossa staining (Figure 4). Cells also expressed typical genes found in bone tissue such as osteopontin, osteocalcin, and Wnt-1.

Figure 4.

AFSCs plasticity. AFSCs were seeded in 6-well plates and cultivated with osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic inductor medium for 3 weeks. (a) Control cells cultivated without inductor medium (magnification: 40x). (b) Osteogenic differentiation was assessed by von Kossa (calcium deposits in black) and (c) Alizarin Red (calcium deposits in red) staining. Adipogenic differentiation was assessed by Oil Red O staining. (d) Differentiated cells without staining (magnification: 40x), (e) differentiated cells stained by Oil Red O (cytoplasmic lipids droplets in red, 400x). (f) Chondrogenic differentiation was confirmed with H&E (magnification: 400x) (g) and immunofluorescence staining with antibodies against collagen type II (400x). (h) Osteogenic gene expression was determined by RT-PCR; products were electrophorezed and visualized under ultraviolet light in 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide (100 bp molecular weight, control (water), osteopontin [OPN], osteocalcin [OCN] and Wnt-1). (i) Typical adipogenic gene expression was determined by RT-PCR (100 bp molecular weight, control (water), PPAr-γ and lipoprotein lipase). (j) Chondrogenic gene expression was determined by RT-PCR (100 bp molecular weight, control (water), collagen type II, perlecan, and syndecan).

Adipogenic differentiation was confirmed by Oil Red O staining. Cytoplasmic lipid droplets appeared stained in red. They also expressed adipocytes genes as PPAr-γ and lipoprotein lipase.

AFSCs were also able to differentiate into chondrogenic tissue after stimulation with TGF-β I and dexamethasone for 21 days. Histological sections from treated pellet showed a typical structure of cartilage tissue. The presence of collagen type II was detected by immunofluorescence staining. Differentiated cells expressed genes typically found in condroblasts, such as syndecan, perlecan and collagen type II (Figure 4).

3.5. Cryopreservation

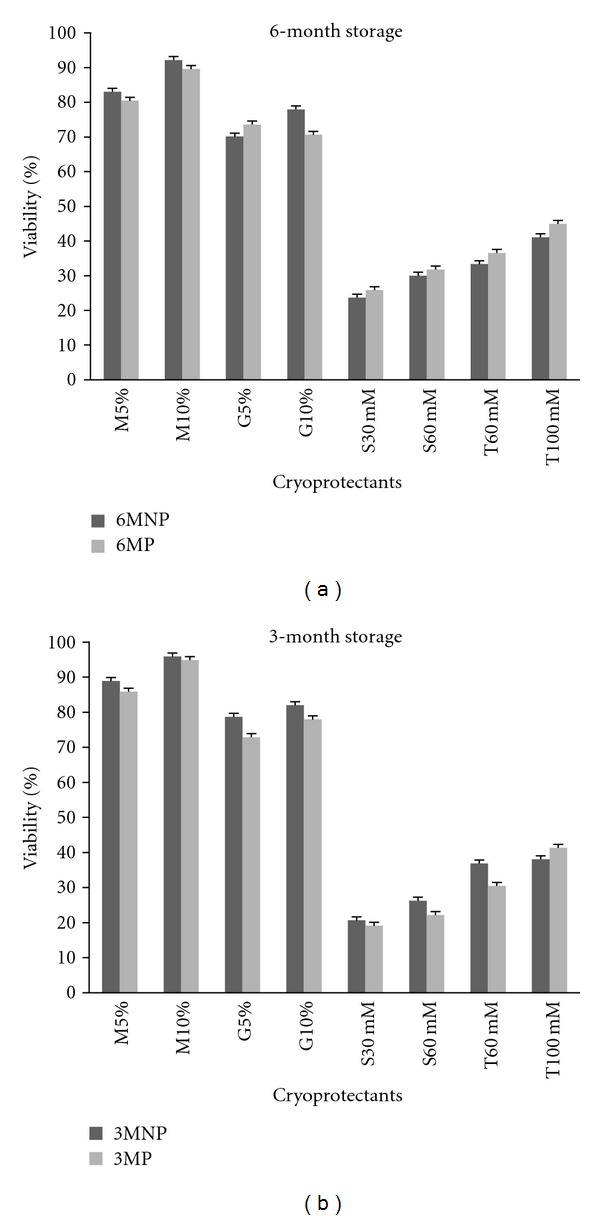

AFSCs viability after thawing did not present statistical difference when compared the nonprogrammed and programmed time freezing protocols after 3 and 6 months storage (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

AFSCs viability comparing nonprogrammed and programmed freezing protocols. we did not have statistic differences in AFSCs viability when we compared the two freezing methods tested. (a) AFSCs viability after 6 months in programmed and nonprogrammed freezing using different cryoprotectants. (b) AFSCs viability after 3 months in programmed and nonprogrammed freezing using different cryoprotectants. M-Me2SO, G-glycerol, S-sucroses and T-trehalose. Means were compared by one-way ANOVA Dunnett posttest (*P < 0.05).

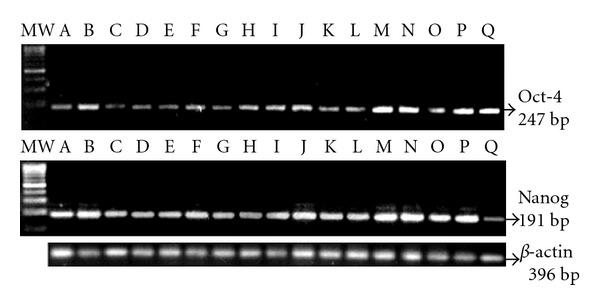

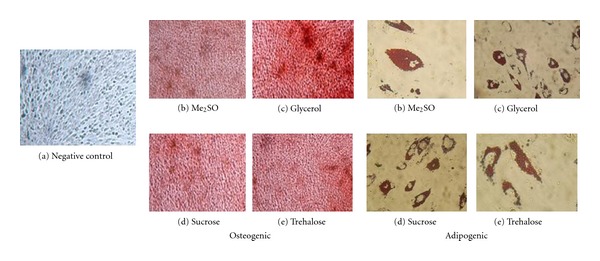

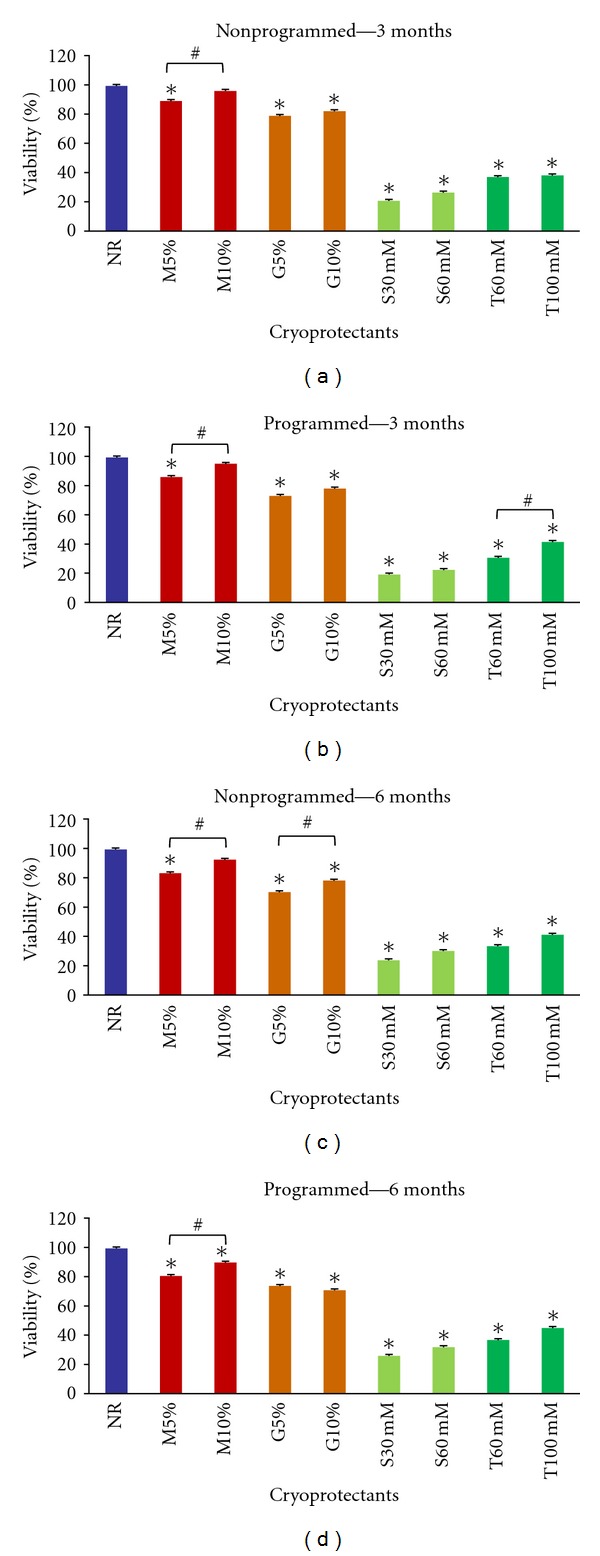

All evaluated cryoprotectants preserved the basic features of AFSCs, as Oct-4 and Nanog genes expression (Figure 6), surface markers (CD29, CD44, and CD105 positive; CD14, CD34, and CD45 negative, Tables 2 and 3) and differentiation multipotential after thawing (Figure 7). Although, Me2SO (5 and 10%) and glycerol (5 and 10%) showed higher rates of viability than the extracellular cryoprotectants, sucrose and trehalose (Figure 8).

Figure 6.

AFSCs were thawed, total RNA was extracted, and Oct-4 and Nanog gene expression was determined by RT-PCR in 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide after freezing with different cryoprotectants. Human β-actin was used as endogenous control. MW: 100 bp molecular weight; A: 5% Me2SO nonprogrammed; B: 5% Me2SO, programmed; C: 10% Me2SO, nonprogrammed; D: 10% Me2SO, programmed; E: 5% Glycerol, nonprogrammed; F: 5% Glycerol, programmed; G: 10% Glycerol, nonprogrammed; H: 10% Glycerol, programmed; I: 30 mM Sucrose, nonprogrammed; J: 30 mM Sucrose, programmed; K: 60 mM Sucrose, nonprogrammed; L: 60 mM Sucrose, programmed; M: 60 mM Trehalose, nonprogrammed; N: 60 mM Trehalose, programmed; O: 100 mM Trehalose, nonprogrammed; P: 100 mM Trehalose; programmed; Q: positive control (Ntera-2.c1D1 cell line).

Table 2.

After nonprogrammed freezing, AFSCs (n = 5) maintained their specific mesenchymal membrane proteins evaluated by flow cytometry (CD29, CD44, and CD105 positive; CD14, CD34, and CD45 negative). The number of acquired events was 15,000 in each acquisition. Results are shown as percentage ±SEM.

| Nonprogrammed | CD14 PE | CD34 FITC | CD45 FITC | CD29 PE | CD44 FITC | CD105 PE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Me2SO 5% | 1.22 ± 0.25 | 0.29 ± 0.25 | 0.35 ± 0.16 | 98.30 ± 1.05 | 99.26 ± 0.39 | 99.01 ± 1.03 |

| Me2SO 10% | 1.02 ± 0.18 | 0.74 ± 0.22 | 5.80 ± 2.02 | 99.81 ± 0.11 | 99.90 ± 0.07 | 99.26 ± 0.36 |

| Glycerol 5% | 0.94 ± 0.44 | 0.44 ± 0.16 | 0.84 ± 0.31 | 99.54 ± 0.26 | 99.91 ± 0.06 | 98.92 ± 0.95 |

| Glycerol 10% | 0.87 ± 0.56 | 0.09 ± 0.27 | 0.16 ± 0.09 | 99.10 ± 0.33 | 99.09 ± 0.46 | 99.33 ± 0.51 |

| Sucrose 30 mM | 1.06 ± 0.23 | 0.81 ± 0.51 | 1.08 ± 0.73 | 99.74 ± 0.04 | 99.69 ± 0.18 | 99.44 ± 0.12 |

| Sucrose 60 mM | 0.95 ± 0.65 | 1.14 ± 0.89 | 3.49 ± 0.88 | 99.43 ± 0.25 | 99.57 ± 0.32 | 98. 26 ± 1.39 |

| Trehalose 60 mM | 1.93 ± 0.26 | 0.36 ± 0.31 | 0.37 ± 0.26 | 99.86 ± 0.28 | 99.98 ± 0.01 | 98.24 ± 1.17 |

| Trehalose 100 mM | 0.82 ± 0.72 | 0.48 ± 0.28 | 0.79 ± 0.17 | 99.91 ± 0.05 | 99.08 ± 0.74 | 99.54 ± 0.09 |

Table 3.

After programmed freezing, AFSCs (n = 5) maintained their specific mesenchymal membrane proteins evaluated by flow cytometry (CD29, CD44, and CD105 positive; CD14, CD34, and CD45 negative). The number of acquired events was 15,000 in each acquisition. Results are shown as percentage ±SEM.

| Programmed | CD14 PE | CD34 FITC | CD45 FITC | CD29 PE | CD44 FITC | CD105 PE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Me2SO 5% | 1.88 ± 0.35 | 0.58 ± 0.22 | 0.85 ± 0.53 | 96.06 ± 2.61 | 97.03 ± 2.06 | 98.82 ± 1.06 |

| Me2SO 10% | 0.92 ± 0.46 | 0.75 ± 0.13 | 0.76 ± 0.44 | 99.67 ± 0.16 | 99.88 ± 0.10 | 99.02 ± 0.15 |

| Glycerol 5% | 0.91 ± 0.74 | 0.18 ± 0.08 | 0.39 ± 0.29 | 99.48 ± 0.40 | 99.85 ± 0.16 | 99.51 ± 0.17 |

| Glycerol 10% | 1.76 ± 0.96 | 1.07 ± 0.97 | 1.12 ± 1.01 | 99.71 ± 0.16 | 99.87 ± 0.08 | 99.11 ± 0.39 |

| Sucrose 30 mM | 0.62 ± 0.48 | 0.22 ± 0.14 | 0.48 ± 0.15 | 99.29 ± 0.19 | 99.95 ± 0.03 | 99.65 ± 0.06 |

| Sucrose 60 mM | 1.36 ± 0.08 | 0.96 ± 0.06 | 1.51 ± 0.83 | 99.35 ± 0.28 | 99.17 ± 0.66 | 99.02 ± 0.20 |

| Trehalose 60 mM | 1.25 ± 0.41 | 0.31 ± 0.25 | 0.48 ± 0.25 | 97.77 ± 1.31 | 99.85 ± 0.11 | 98.90 ± 0.66 |

| Trehalose 100 mM | 0.53 ± 0.88 | 0.46 ± 0.36 | 0.60 ± 0.56 | 99.50 ± 0.36 | 99.83 ± 0.18 | 98.94 ± 0.76 |

Figure 7.

After thawing, AFSCs freezed with different cryoprotectants ((b) Me2SO, (c) glycerol, (d) sucrose, and (e) trehalose) were cultivated with osteogenic and adipogenic inductor medium. Differentiation was confirmed by Alizarin Red and Oil Red O staining after 21 days. (a) Control cells without inductor. Calcium deposits appear in red. All cryoprotectants tested maintained osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation potential of AFSCs after storage for 6 months.

Figure 8.

AFSCs viability comparing different cryoprotectants (Me2SO, glycerol, sucrose, and trehalose) and programmed and nonprogrammed freezing protocols after 3 and 6 months. (a) viability in nonprogrammed method for 3 months; (b) viability in programmed method for 3 months; (c) viability in nonprogrammed method for 6 months; (d) viability in programmed method for 6 months. 10% Me2SO showed the higher viability rate similar to NR control in all cases. NR-AFSCs viability control measured before freezing procedure. M-Me2SO, G-glycerol, S-sucrose, and T-trehalose. Means were compared by one-way ANOVA Dunnett's (***P < 0.05) and Bonferroni (#P < 0,05) post tests.

4. Discussion

The interest of mesenchymal stem cells in the scientific community has arisen due to their peculiar characteristics. Among them, the highlights are proliferative capacity and differentiation potential [16–18]. Human amniotic fluid from second trimester of pregnancy was appointed recently as an alternative source for MSCs [19, 20]; however, some features, especially about cryopreservation analysis, are not fully described. In the present study, we isolated AFSCs and examined two freezing protocols as well as distinct cryoprotectants which could maintain high viability and stemness of AFSCs after cryopreservation.

Primary culture of human amniotic fluid revealed the presence of fibroblast-like cells capable of adhesion and colonies formation in plastic dish surface. These cells were classified as mesenchymal stem cells by their characteristics, as follows.

AFSCs doubling time (30 hours) founded was similar with that described elsewhere [21], and this demonstrated the high proliferative potential of these cells.

Key gene expression profile, such as Oct-4 and Nanog, is essential to determine the undifferentiated stem cells status. These genes are commonly found in pluripotent stem cells and cancer cells [22]. Specific surface markers were investigated using a panel of membrane antibodies that virtually exclude the presence of contaminating hematopoietic cells and examined proteins commonly present in MSCs, as CD29 (β-integrin), CD44 (hyaluronic acid receptor), CD90 (Thy-1) and CD105 (endoglin). Data also showed the high differentiation potential of the AFSCs in osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic lineages, thus confirming their multipotent state.

Cell cultures require cooling methods for long-time storage, and the choice of freezing protocol used must be done carefully to avoid cell death and, mainly, to maintain the cell characteristics, as in this case, AFSCs proliferation and plasticity properties [23]. With this aim our study compared two freezing protocols: a programmed-rate cooling and, a more conventional approach, nonprogrammed time freezing, both with subsequent storage in liquid nitrogen.

The cooling rate is a critical step during freezing. If cooling is sufficiently slow, the cell is able to lose water rapidly enough by exosmosis to concentrate the intracellular solutes sufficiently to eliminate supercooling and maintain the chemical potential of intracellular water in equilibrium with that of extracellular water. The result is that the cell dehydrates and does not freeze intracellularly. But if the cell is cooled too rapidly, it is not able to lose water fast enough to maintain equilibrium; it becomes increasingly supercooled and eventually attains equilibrium by freezing intracellularly. Intracellular ice formation leads to cell death [2].

It was observed that the two methods had no effect when compared with each other in cellular viability after thawing. Therefore, a nonprogrammed method should make cryopreservation more convenient and less costly because the use of complex equipment for controlled-rate freezing is avoided.

Cryoprotectants are essential to maintain the cell viability and function for storage at very low temperatures, including for amniotic fluid-derived stem cells [24, 25]. In this study, different cryoprotectants were tested, two intracellular compounds that impair crystal ice formation inside the cells (Me2SO and glycerol) and two extracellular agents which improve freezing osmotic imbalance (sucrose and trehalose). Me2SO is the most widely used cryoprotectant [21, 26], but several studies report their potential to induce neuronal differentiation in stem cells [5, 27]. This fact together with their cell toxicity in room temperature led us to search for other cryoprotectants to use for freezing AFSCs. Neuronal differentiation promoted by Me2SO was not observed in our study since cells were washed with α-MEM medium right after thawing, eliminating any trace of the cryoprotectant. Therefore, AFSCs frozen with Me2SO kept their Oct-4 and Nanog genes expression and differentiation capacity.

Glycerol, another intracellular cryoprotectant, was compared with Me2SO. Glycerol is also widely used in concentrations of 5 and 10%, in cell cultures. It is described that it does not promote cellular toxicity [28], but its action in AFSCs cryopreservation has not been described so far. Glycerol, both at 5 and 10% has caused lower viability than Me2SO, but yet in acceptable rates for cell culture.

Disaccharides such as sucrose and trehalose have also been widely used as natural cryoprotectants, as excipients for freeze drying and as stabilizers during dehydration. The precise mechanism by which disaccharides act to preserve biological systems during freezing and drying is not well understood. The fact that they do not enter in cells is the main advantage, facilitating their removal after thawing [29]. Sucrose and trehalose led to a low rate of AFSCs viability and, consequently, an increase in lag phase after thawing, maybe because these extracellular agents do not prevent the formation of ice crystals within the cell.

All tested cryoprotectants maintained the Oct-4 and Nanog gene expression and did not alter membrane markers or the plasticity of AFSCs post thawing, which were able to differentiate into bone and fat tissues after thawing.

5. Conclusions

Human amniotic fluid collected in the second trimester of gestation contains mesenchymal stem cells which show a high rate of proliferation in vitro and multipotent profile, as shown by histological and gene expression studies. Both, nonprogrammed and programmed time freezing methods, could be used for AFSCs cryopreservation for 6 months. Although all tested cryoprotectants maintained Oct-4 and Nanog gene expression, typical surface markers, and multilineage differentiation of AFSCs, only Me2SO and glycerol presented workable viability ratio.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos (FINEP), and Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia-Fluidos Complexos (INCT-FCx), Brazil.

References

- 1.Moon JH, Lee JR, Jee BC, et al. Successful vitrification of human amnion-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Human Reproduction. 2008;23(8):1760–1770. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozkavukcu S, Erdemli E. Cryopreservation: basic knowledge and biophysical effects. Journal of Ankara Medical School. 2002;24(4):187–196. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis JM, Rowley SD, Braine HG, Piantadosi S, Santos GW. Clinical toxicity of cryopreserved bone marrow graft infusion. Blood. 1990;75(3):781–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neuhuber B, Gallo G, Howard L, Kostura L, Mackay A, Fischer I. Reevaluation of in vitro differentiation protocols for bone marrow stromal cells: disruption of actin cytoskeleton induces rapid morphological changes and mimics neuronal phenotype. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2004;77(2):192–204. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mareschi K, Rustichelli D, Novara M, et al. Neural differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells: evidence for expression of neural markers and eag K+ channel types. Experimental Hematology. 2006;34(11):1563–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prusa AR, Marton E, Rosner M, et al. Neurogenic cells in human amniotic fluid. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;191(1):309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stroncek DF, Fautsch SK, Lasky LC, Hurd DD, Ramsay NKC, McCullough J. Adverse reactions in patients transfused with cryopreserved marrow. Transfusion. 1991;31(6):521–526. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1991.31691306250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Syme R, Bewick M, Stewart D, Porter K, Chadderton T, Glück S. The role of depletion of dimethyl sulfoxide before autografting: on hematologic recovery, side effects, and toxicity. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2004;10(2):135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedenstein AJ, Deriglasova UF, Kulagina NN, et al. Precursors for fibroblasts in different populations of hematopoietic cells as detected by the in vitro colony assay method. Experimental Hematolology. 1974;2(2):83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barzilay R, Kan I, Ben-Zur T, Bulvik S, Melamed E, Offen D. Induction of human mesenchymal stem cells into dopamine-producing cells with different differentiation protocols. Stem Cells and Development. 2008;17(3):547–554. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stock P, Brückner S, Ebensing S, Hempel M, Dollinger MM, Christ B. The generation of hepatocytes from mesenchymal stem cells and engraftment into murine liver. Nature Protocols. 2010;5(4):617–627. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prusa AR, Hengstschläger M. Amniotic fluid cells and human stem cell research: a new connection. Medical Science Monitor. 2002;8(11):253–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anker PS, Scherjon SA, Kleijburg-van der Keur C, et al. Amniotic fluid as a novel source of mesenchymal stem cells for therapeutic transplantation. Blood. 2003;102(4):1548–1549. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fauza D. Amniotic fluid and placental stem cells. Best Practice and Research. 2004;18(6):877–891. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prusa AR, Marton E, Rosner M, Bernaschek G, Hengstschläger M. Oct-4-expressing cells in human amniotic fluid: a new source for stem cell research? Human Reproduction. 2003;18(7):1489–1493. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdallah BM, Kassem M. Human mesenchymal stem cells: from basic biology to clinical applications. Gene Therapy. 2008;15(2):109–116. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolf CM, Cho E, Tuan RS. Mesenchymal stromal cells. Biology of adult mesenchymal stem cells: regulation of niche, self-renewal and differentiation. Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2007;9(1, article 204) doi: 10.1186/ar2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi Y, Hu G, Su J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: a new strategy for immunosuppression and tissue repair. Cell Research. 2010;20(5):510–518. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Streubel B, Martucci-Ivessa G, Fleck T, Bittner RE. In vitro transformation of amniotic cells to muscle cells-background and outlook. Wien Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1996;146(9-10):216–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai MS, Lee JL, Chang YJ, Hwang SM. Isolation of human multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from second-trimester amniotic fluid using a novel two-stage culture protocol. Human Reproduction. 2004;19(6):1450–1456. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roubelakis MG, Pappa KI, Bitsika V, et al. Molecular and proteomic characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from amniotic fluid: comparison to bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells and Development. 2007;16(6):931–951. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zangrossi S, Marabese M, Broggini M, et al. Oct-4 expression in adult human differentiated cells challenges its role as a pure stem cell marker. Stem Cells. 2007;25(7):1675–1680. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu WX, Luo MJ, Huang P, et al. Comparative study between slow freezing and vitrification of mouse embryos using different cryoprotectants. Reproduction in Domestic Animals. 2009;44(5):788–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2008.01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCullough J, Haley R, Clay M, Hubel A, Lindgren B, Moroff G. Long-term storage of peripheral blood stem cells frozen and stored with a conventional liquid nitrogen technique compared with cells frozen and stored in a mechanical freezer. Transfusion. 2010;50(4):808–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seo JM, Sohn MY, Suh JS, Atala A, Yoo JJ, Shon YH. Cryopreservation of amniotic fluid-derived stem cells using natural cryoprotectants and low concentrations of dimethylsulfoxide. Cryobiology. 2011;62(3):167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miranda-Sayago JM, Fernandez-Arcas N, Benito C, Reyes-Engel A, Herrero JR, Alonso A. Evaluation of a low cost cryopreservation system on the biology of human amniotic fluid-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2012.01.003. Cryobiology. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sputtek A, Jetter S, Hummel K, Kühnl P. Cryopreservation of peripheral blood progenitor cells: characteristics of suitable techniques. Beiträge zur Infusionstherapie und Transfusionsmedizin. 1997;34:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnaud FG. Cryopreservation of human platelets with 1.4 M glycerol at -196°C. Thrombosis Research. 1989;53(6):585–594. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(89)90148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodrigues JP, Paraguassú-Braga FH, Carvalho L, Abdelhay E, Bouzas LF, Porto LC. Evaluation of trehalose and sucrose as cryoprotectants for hematopoietic stem cells of umbilical cord blood. Cryobiology. 2008;56(2):144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]