Abstract

Background & objectives:

Protecting myocardium from ischaemia-reperfusion (I-R) injury is important to reduce the complication of myocardial infarction (MI) and interventional revascularization procedures. In the present study, the cardioprotective potential of hydroalcoholic extract of Andrographis paniculata was evaluated against left anterior descending coronary artery (LADCA) ligation-induced I-R injury of myocardium in rats.

Methods:

MI was induced in rats by LADCA ligation for 45 min followed by reperfusion for 60 min. The rats were divided into five experimental groups viz., sham (saline treated, but LADCA was not ligated), I-R control (saline treated + I-R), benazepril (30 mg/kg + I-R), A. paniculata (200 mg/kg per se) and A. paniculata (200 mg/kg + I-R). A. paniculata was administered orally for 31 days. On day 31, rats were subjected to the I-R and cardiac function parameters were recorded. Further, rats were sacrificed and heart was excised for biochemical and histopathological studies.

Results:

In I-R control group, LADCA ligation resulted in significant cardiac dysfunction evidenced by reduced haemodynamic parameters; mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR). The left ventricular contractile function was also altered. In I-R control group, I-R caused decline in superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and reduced glutathione (GSH) as well as leakage of myocytes injury marker enzymes, creatine phosphokinase-MB (CK-MB) isoenzyme and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and enhanced lipid peroxidation product, malonaldialdehyde (MDA). However, rats pretreated with A. paniculata 200 mg/kg showed favourable modulation of haemodynamic and left ventricular contractile function parameters, restoration of the myocardial antioxidants and prevention of depletion of myocytes injury marker enzymes along with inhibition of lipid peroxidation. Histopathological observations confirmed the protective effects of A. paniculata. The cardioprotective effects of A. paniculata were found comparable to that of benazepril treatment.

Interpretation & Conclusions:

Our results showed the cardioprotective effects of A. paniculata against I-R injury likely result from the suppression of oxidative stress and preserved histoarchitecture of myofibrils along with improved haemodynamic and ventricular functions.

Keywords: Andrographis paniculata, cardiac function, ischaemia reperfusion injury, myocardial injury, myocardium

Myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion (I-R) is clinically relevant to conditions such as myocardial infarction (MI), coronary angioplasty, thrombolytic therapy, coronary revascularization and heart transplantation. The reperfusion, although clearly beneficial for the heart, is associated with myocardial injury1. Myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion has been reported to be associated with increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS result in depletion of endogenous antioxidant network, membrane permeability changes resulting in increased lipid peroxidation products and consequently, depressed contractile function2,3. Among several pharmacological agents, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are shown to be useful in attenuation of ventricular remodelling and reducing infarction and incidences of reperfusion-induced arrhythmias4. Benazepril, an ACE inhibitor has been shown to ameliorate cardiac dysfunction and oxidative stress in ischaemic myocardium owing to its antioxidant property5. In view of the critical role of oxidative stress in I-R injury, extensive effort has been made to develop therapies and interventions with antioxidants, which may attenuate or reduce oxidative stress and consequent cardiac dysfunction6,7. Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of medicinal plants and phytochemicals as a phytotherapeutic agent in ischaemic heart disease as these serve as excellent candidates against oxidative stress associated conditions8–10.

Andrographis paniculata Nees (Family; Acanthaceae), popularly known as ‘Kalmegh’ a common Indian dietary component, has been used in Indian and Chinese traditional medicine11. Pharmacological studies have demonstrated its hepatoprotective12, anti-inflammatory13, immunostimulant14, antihy-perglycaemic15 and cardioprotective properties16,17. The active component of A. paniculata such as diterpenoids compounds (andrographolide, 14-de-oxy-11, 12-didehydro andrographolide and neo-andrographolide), collectively termed as andrographolides have shown several pharmacological properties including antioxidant, vasorelaxant, antiplatelet, hypotensive and anti-inflammatory activities11,18. Andrographolide has also been shown to protect against hypoxia-reperfusion injury in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes19. Phytotherapeutic studies have revealed that whole herb extract is an effective modality for therapeutic and preventive purposes due to its complex composition and interactions, which may modulate signal transduction and metabolic pathways8,20. Though, available preliminary studies indicate its cardioprotective potential in myocardial injury, the possible mechanism involved in cardioprotection remains obscure. The functional and biochemical alterations which occur during MI in humans are experimentally represented in a clinically relevant animal model involving left anterior descending coronary artery (LADCA) ligation-induced ischaemia and reperfusion (I-R) injury12. Therefore, the present study was carried out to assess the preventive effects of hydroalcoholic extract of A. paniculata against LADCA ligation induced I-R injury measuring haemodynamic, biochemical and histopathological parameters in rats. Benazepril was used as a reference drug.

Material & Methods

All chemicals used in present study were obtained from Sigma Chemicals, USA. Lyophilized hydroalcoholic extract of A. paniculata was procured from Sanat Laboratories, New Delhi, India. The total andrographolide content determined in the extract was not less than 10 per cent w/w. The dose of A. paniculata (200 mg/kg) used in the present study was selected on the basis of a previous pilot study21 in the isoproterenol model of myocardial injury in rats. Benazepril 30 mg/kg was selected on the basis of a previous published report showing its cardioprotective activity against I-R injury5.

Experimental animals: Male Wistar albino rats (10 to 12 wk old, weighing 150 to 200 g) obtained from Central Animal House Facility, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi were used in the study. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee. The animals were housed at standard laboratory conditions and fed diet and water ad libitum.

Experimental design:

Group I (Sham) - Rats were administered 0.9 per cent saline (2 ml/kg/day) once daily for 31 days and on 31st day underwent the entire surgical procedure except LADCA ligation or reperfusion.

Group II (I-R control) - Rats were administered normal saline (0.9%) orally for 31 days and on 31st day underwent LADCA ligation for 45 min followed by 60 min of reperfusion.

Group III (Benazepril) - Rats were administered benazepril (30 mg/kg) orally for 31 days and on 31st day underwent LADCA ligation for 45 min followed by 60 min of reperfusion.

Group IV (A. paniculata 200 mg/kg) - Rats were administered hydroalcoholic extract of A. paniculata (200 mg/kg) orally for 31 days and on 31st day underwent the entire surgical procedure except LADCA ligation or reperfusion.

Group V (A. paniculata 200 mg/kg + I-R) - Rats were administered A. paniculata (200 mg/kg) orally for 31 days and on 31st day underwent LADCA ligation for 45 min followed by 60 min of reperfusion.

Assessment of haemodynamic parameters: Myocardial ischaemia was produced by a temporary tightening of the silk ligature around the LADCA9. Briefly, rat was anaesthetized, ventilated and right carotid artery was cannulated and connected to CARDIOSYSCO-101 (Experimentria, Hungary) using a pressure transducer for the measurement of mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR). A left thoracotomy was performed and a wide bore (1.5 mm) sterile metal cannula connected to a pressure transducer (Gould Statham P23ID, USA) was inserted into the cavity of the left ventricle for recording left ventricular pressure dynamics, such as left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP); peak positive pressure development [(+)LVdP/dt], and peak negative pressure decline [(-)LVdP/dt], representing preload, contractility and relaxation, respectively on Polygraph (Grass 7D, USA). Myocardial ischaemia was produced by one stage occlusion of the LADCA, 1-2 mm below the junction of pulmonary conus by pressing the polyethylene tubing against the ventricular wall. This was designated time point zero. The animals then underwent 45 min of ligation-induced ischaemia and further the myocardium was reperfused by releasing the snare gently for a period of 60 min. After completion of reperfusion, the animals were sacrificed and the heart was excised for biochemical and histopathological studies.

Biochemical analysis of heart: An aliquot of 0.5 ml of heart homogenate was used for assay of reduced glutathione (GSH)22 and malondialdehyde (MDA)23. The remaining homogenate was centrifuged and supernatant was used for the estimation of myocardial superoxide dismutase (SOD)24, catalase (CAT)25, glutathione peroxidase (GPx)26, creatine-phospokinase-MB (CK-MB)27 isoenzyme, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)28 and protein29.

Assessment of histopathology of myocardium: Formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and observed under light microscope.

Statistical analysis: Data were analyzed using ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple range test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The paired data were compared using Student's t-test.

Results

There was no significant difference in baseline values among different experimental groups. The mortality rate of 8 per cent was observed in the I-R control group. The reasons for mortality were reperfusion-induced arrhythmias or erroneous cannulation.

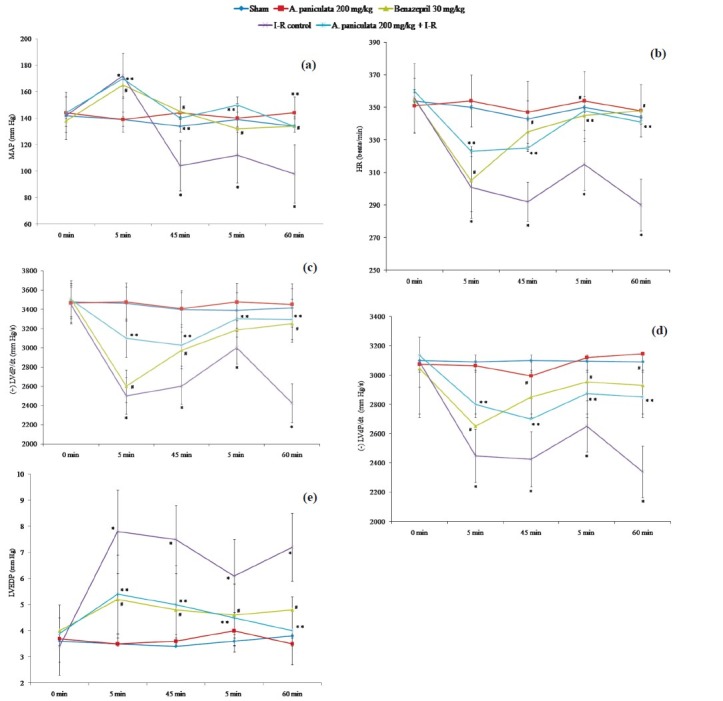

A. paniculata per se did not show significant effect on functional parameters, antioxidants, myocyte injury marker enzymes, lipid peroxidation and histopathology of the myocardium. In I-R control group, 5 min after ligation a significant increase in MAP was observed, it decreased at 45 min of ischaemia and slightly increased after reperfusion but again declined throughout the reperfusion period compared to sham group (Fig. 1a). A. paniculata pretreatment significantly restored MAP as compared to I-R control group at the end of ischaemia as well as reperfusion period (Fig. 1a). Similarly, a significant decrease in HR was observed after ligation and upon reperfusion, there was a slight increase. However, it declined further and remained significantly (P<0.05) depressed throughout the reperfusion in I-R control group as compared to sham group (Fig. 1b). Pretreatment with A. paniculata significantly increased HR at the end of ischaemia (at 45 min) and reperfusion (at 60 min) both as compared to I-R control group (Fig. 1b). The improvement in MAP and HR with A. paniculata was comparable to benazepril treatment.

Fig. 1.

Effect of A. paniculata pretreatment on (a) mean arterial pressure (MAP), (b) heart rate (HR) (c) contractility [(+)LVdP/dt], (d) relaxation [(-)LVdP/dt], and (e) left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP) during ischaemia-reperfusion.

N=8; values are mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, when compared to sham; **P<0.05, when compared to I-R control, #<0.05, when compared to I-R control.

Effect of A. paniculata on left ventricular function: In I-R control group, on ligation (at 5 min), a significant depression in (+)LVdP/dt was recorded and it remained depressed till the end of ischaemia (at 45 min). Upon reperfusion (at 5 min), (+)LVdP/dt increased slightly but significantly (P<0.05) declined further as compared to sham (Fig. 1d). Similar to contractility, a significant depression in (-)LVdP/dt was also recorded in the I-R control group as compared to sham (Fig. 1c). Pretreatment with A. paniculata significantly improved (+)LVdP/dt (Fig. 1d) and (-)LVdP/dt (Fig. 1c), both at the end of ischaemia and reperfusion as compared to I-R control group. The improvement in (+)LVdP/dt and (-)LVdP/dt with A. paniculata pretreatment were observed similar to benazepril treatment in ischaemia as well as reperfusion period. In I-R control group after ligation (at 5 min), an abrupt increase in LVEDP was observed which remained elevated till the end of the ischaemia. Upon reperfusion, no significant reduction in LVEDP was observed as comparison to sham group (Fig. 1e). A. paniculata pretreatment significantly reduced the LVEDP along with other altered ventricular functions as compared to the I-R control group, similar to benazepril treatment (Fig. 1e).

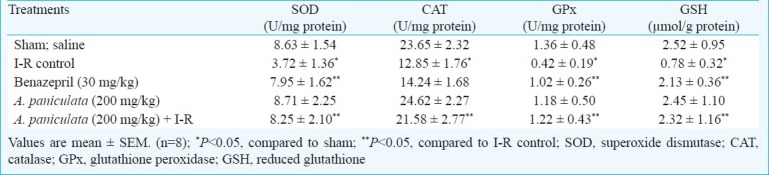

Effect of A. paniculata on antioxidant status: In I-R control group, a significant (P<0.05) decrease in the activities of SOD, CAT GPx and GSH was observed compared to sham group (Table I). Pretreatment with A. paniculata caused restoration of myocardial antioxidants. Benazepril also significantly (P<0.05) restored the SOD, GSH and GPx in comparison with I-R control group.

Table I.

Effect of A. paniculata pretreatment on myocardial antioxidants

I-R induced a significant (P<0.05) increase in lipid peroxidation product, MDA as compared to sham group (Table II). However, A. paniculata significantly inhibited lipid peroxidation, MDA in comparison with I-R control group. In I-R control group, a significant (P<0.05) decrease in myocardial CK-MB isoenzyme and LDH was observed as compared to sham group (Table II). However, pretreatment with A. paniculata significantly prevented the leakage of CK-MB isoenzyme and LDH activities as evidenced by reduced depletion of CK-MB and LDH from heart as compared to I-R control group (Table II). Benazepril treatment also showed similar effect.

Table II.

Effect of A. paniculata pretreatment on myocyte injury markers and lipid peroxidation

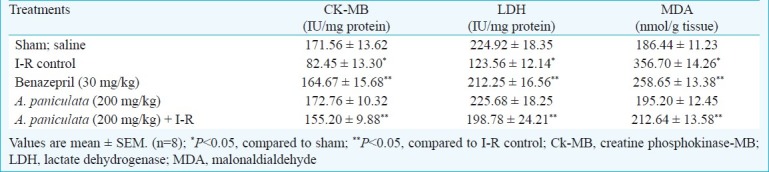

Effect of A. paniculata on myocardial histopathology: The histopathological observations were graded on the basis of myonecrosis, inflammatory cells and oedema and scored as (-) nil, (+) mild, (++) moderate and (+++) severe. Sham group showed normal histoarchitecture of myocardium with no evidence of oedema, myonecrosis and inflammatory cells (Fig. 2a). However, I-R control group (Fig. 2b) showed marked myocardial necrosis, membrane damage, infiltration of inflammatory cells, extravasation of RBCs, oedema and inflammation compared to sham group. Animals pretreated only with A. paniculata (Fig. 2c) showed a normal myocardial histoarchitecture resembling to sham group. Benazepril markedly reduced myonecrosis, oedema and inflammation (Fig. 2d). Similarly, rats pretreated with A. paniculata showed distinct protection from I-R injury as evidenced by reduced oedema, myonecrosis and infiltration of inflammatory cells (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2.

Light micrograph (H&Ex100) of rat's myocardium (a) Sham group showing normal histoarchitecture of myocardium, (b) I-R control group showing confluent necrosis of myofibrils, edema and infiltration of inflammatory cells with extravasations of red blood cells, (c) Benazepril 30 mg/kg showing reduced myonecrosis, oedema and infiltration of inflammatory cells, (d) A. paniculata 200 mg/kg pretreatment showing normal histoarchitecture of myocardium and (e) A. paniculata 200 mg/kg + I-R group showing resemblance to normal myocardial histoarchitecture with lessened necrosis and oedema.

Discussion

Our results showed that pretreatment with A. paniculata reduces myocardial I-R injury in rats by reducing myonecrosis, oedema and inflammation along with improving cardiac function and tissue defense network. The LADCA ligated ischaemia and reperfusion model of myocardial infarction is a useful experimental tool in the development and assessment of anti-ischaemic interventions30.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that I-R injury is related to the formation of oxygen derived free radicals and lipid peroxidation in the myocardium1–3. To defend against free radicals mediated injury, heart like many other organs is equipped with its own defensive system, which includes SOD, CAT and glutathione redox network6,7. In our study, a significant elevation in the level of stable degradation product of the oxygen derived free radicals and lipid peroxides, MDA depicts the myocardial membrane damage due to I-R induced injury. Besides MDA, a significant decrease in levels of SOD and CAT further confirmed the occurrence of oxidative stress in I-R control group. Following I-R injury, an abrupt depletion of GSH along with a concomitant decrease in GPx depicts a destabilized antioxidant milieu of heart.

Present study showed that pre-treatment with A. paniculata reduced the formation of MDA in myocardium induced by I-R, and a significant rise in the activities of SOD and CAT. The activities of SOD and level of MDA have been shown correlated negatively and a similar trend was observed in present study9. Further, an increase in GSH with concomitant restoration of GPx activity by A. paniculata pre-treatment indicates induction of glutathione antioxidant network as shown earlier19. Benazepril pretreatment has been also observed to restore the antioxidant enzymes and decrease lipid peroxidation in agreement to previous study5.

I-R induced myocardial injury caused a significant decrease in myocytes specific injury marker enzymes, CK-MB isoenzyme and LDH. Leakage of CK-MB isoenzyme and LDH from myocardial tissues to blood is diagnostic of acute myocardial infarction. Alteration in myocardial membrane integrity, fluidity and permeability following lipid peroxidation has been believed to be a reason for the leakage of myocytes injury marker enzymes31. A. paniculata pre-treatment prevented the leakage of CK-MB isoenzyme and LDH enzyme attributed to inhibition of lipid peroxidation and preservation of myocardial membranes.

It is well documented that increased generation of ROS during I-R injury results in haemodynamic impairment and left ventricular dysfunction9. In the present study, following myocardial I-R injury, a significant fall in MAP, HR, (+)LVdP/dt, (-)LVdP/dt and a striking elevation in LVEDP indicated haemodynamic impairment and ventricular dysfunction similar to previous studies9. The (-)LVdP/dt was significantly depressed following I-R injury indicating a diastolic dysfunction. In the conditions of I-R, deteriorated myocardial contractile function may causes significant fall in MAP. Normally, a fall in MAP due to coronary occlusion is expected to increase HR, and myocardial contractility by activating the baroreceptor reflex, which may subsequently result in reflex vasoconstriction and thus worsening the imbalance, between myocardial oxygen demand and supply9. However, none of these effects have been observed in the present study due to I-R induced injury to inotropic and chronotropic function of the heart. The heart rate was observed depressed throughout I-R indicating the injured state of myocardium following I-R induced myocardial injury.

Benazepril treatment showed a decrease in LVEDP and improved MAP as well as contractility and relaxation in comparison to I-R control group. The restorative effect of benazepril on altered haemodynamics and ventricular function is indicative of its cardioprotective effect5. A. paniculata pre-treatment not only decreased LVEDP (a marker of preload), but also preserved the left ventricular function contractility and relaxation as evidenced by increased (+)LVdP/dt (inotropic effect) and (-)LVdP/dt (lusitropic effect).

In previous studies10,11, andrographolide has been demonstrated to exhibit potent antihypertensive activity by reducing MAP and HR. It is likely that the profound hypotension caused by A. paniculata may potentially trigger cardioprotective response by opening of the vanilloid transient receptor potential (TRPV) channels implicated in osmoregulation and regulation of vascular tone32. TRPV activation has been considered to result in smooth muscle hyperpolarization and arterial dilation by the increased number of Ca2+ sparks that activate large conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channels, and the resulting increase in potassium current causes hyperpolarization and arterial dilation. This may be an underlying cause for decrease in blood pressure with the use of andrographoliode rich extract used in the present study. Simultaneously, the vasorelaxant, antioxidant and antiplatelet effect of A. paniculata may be attributed to its cardioprotective effect11,18. Apart from improvement in functional and biochemical parameters, histopathological observations further supported the cardioprotective effect of A. paniculata. Appearance of the near normal morphology of cardiomyocytes on pretreatment with A. paniculata demonstrates the myocardial salvaging effect of A. paniculata and was comparable with benazepril.

In conclusion, the present findings substantiated cardioprotective potential of A. paniculata against I-R injury of myocardium in rats. Restoration of antioxidants, favourable recovery of haemodynamics and ventricular function along with preservation of myofibers were shown to underlie the cardioprotective effect of A. paniculata. Further well controlled clinical studies are warranted to translate these results in humans.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Shriyut Deepak and B.M. Sharma, Department of Pharmacology, AIIMS, for technical assistance and Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, for financial assistance as the award of Research Associate to the first author (SKO).

References

- 1.Monassier JP. Reperfusion injury in acute myocardial infarction. From bench to cath lab Part I: Basic considerations. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;101:491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuzil J, Rayner BS, Lowe HC, Witting PK. Oxidative stress in myocardial ischaemia reperfusion injury: a renewed focus on a long-standing area of heart research. Redox Rep. 2005;10:187–97. doi: 10.1179/135100005X57391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurusamy N, Das DK. Autophagy, redox signaling, and ventricular remodeling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:1975–88. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gross ER, Gross GJ. Pharmacologic therapeutics for cardiac reperfusion injury. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2007;12:367–88. doi: 10.1517/14728214.12.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charan SK, Arora S, Goyal S, Kishore K, Ray R, Chandra NT, et al. Cardioprotective effects of benazepril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, in an ischaemia-reperfusion model of myocardial infarction in rats. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2009;10:201–9. doi: 10.1177/1470320308353059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton KL. Antioxidants and cardioprotection. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1544–53. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180d099e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andreadou I, Iliodromitis EK, Farmakis D, Kremastinos DT. To prevent, protect and save the ischemic heart: antioxidants revisited. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:945–56. doi: 10.1517/14728220903039698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fugh-Berman A. Herbs and dietary supplements in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Prev Cardiol. 2000;3:24–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1520-037x.2000.80355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta SK, Mohanty I, Talwar KK, Dinda A, Joshi S, Bansal P, et al. Cardioprotection from ischemia and reperfusion injury by Withania somnifera: a hemodynamic, biochemical and histopathological assessment. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;260:39–47. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000026051.16803.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan BK-H, Zhang ACY. Andrographis paniculata and the cardiovascular system. Oxidative Stress Dis. 2004;14:441–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarukamjorn K, Nemoto N. Pharmacological aspects of Andrographis paniculata as health and its major diterpenoid constituent Andrographolide. J Health Sci. 2008;54:370–81. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tripathi R, Kamat JP. Free radical induced damages to rat liver subcellular organelles: inhibition by Andrographis paniculata extract. Indian J Exp Biol. 2007;45:959–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen YC, Chen CF, Chiou WF. Andrographolide prevents oxygen radical production by human neutrophils: possible mechanism(s) involved in its anti-inflammatory effect. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:399–406. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puri A, Saxena R, Saxena RP, Saxena KC, Srivastava V, Tandon JS. Immunostimulant agents from Andrographis paniculata. J Nat Prod. 1993;56:995–9. doi: 10.1021/np50097a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang XF, Tan BK. Antihyperglycaemic and anti-oxidant properties of Andrographis paniculata in normal and diabetic rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2000;27:358–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang CY, Tan BK. Mechanisms of cardiovascular activity of Andrographis paniculata in the anaesthetized rat. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;56:97–101. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(97)01509-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoopan N, Thisoda P, Rangkadilok N, Sahasitiwat S, Pholphana N, Ruchirawat S, et al. Cardiovascular effects of 14-deoxy-11, 12-didehydroandrographolide and Andrographis paniculata extracts. Planta Med. 2007;73:503–11. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-967181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thisoda P, Rangkadilok N, Pholphana N, Worasuttayangkurn L, Ruchirawat S, Satayavivad J. Inhibitory effect of Andrographis paniculata extract and its active diterpenoids on platelet aggregation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;553:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woo AY, Waye MM, Tsui SK, Yeung ST, Cheng CH. Andrographolide up-regulates cellular-reduced glutathione level and protects cardiomyocytes against hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:226–35. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.133918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Girish C, Koner BC, Jayanthi S, Rao KR, Rajesh B, Pradhan SC. Hepatoprotective activity of six polyherbal formulations in paracetamol induced liver toxicity in mice. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129:569–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ojha SK, Bharti S, Golechha M, Sharma AK, Rani N, Kumari S, et al. Andrographis paniculata extract protect against isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury by mitigating cardiac dysfunction and oxidative injury in rats. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica-Drug Res. 2012;69:269–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moron MS, Depierre JW, Mannervik B. Levels of glutathione, glutathione reductase and glutathione-s-transferase activities in rat lung and liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;582:67–78. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(79)90289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay of lipid peroxide in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979;95:351–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Misra HP, Fridovich I. The oxidation of phenylhydrazine: superoxide and mechanism. Biochemistry. 1976;15:681–7. doi: 10.1021/bi00648a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aebi H. Catalase. In: Bergmeyer HU, editor. Methods of enzymatic analysis. Weinheim, Germany: Verlag Chemie; 1974. pp. 673–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paglia DE, Valentine WN. Studies on the quantitative and qualitative characterization of erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase. J Lab Clin Med. 1967;70:158–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamprecht W, Stan F, Weisser H, Heinz F. Determination of creatine phosphate and adenosine triphosphate with creatine kinase. In: Bergmeyer HU, editor. Methods of enzymatic analysis. New York: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 1776–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cabaud PG, Wroblewski F. Colorimetric measurements of lactic dehydrogenase activity of body fluids. Am J Clin Pathol. 1958;30:234–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/30.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurements with the Folin-phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hearse DJ, Sutherland FJ. Experimental models for the study of cardiovascular function and disease. Pharmacol Res. 2000;41:597–603. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1999.0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaffe AS, Landt Y, Parvin CA, Abendschein DR, Geltman EM, Ladenson JH. Comparative sensitivity of cardiac troponin I and lactate dehydrogenase isoenzymes for diagnosing acute myocardial infarction. Clin Chem. 1996;42:1770–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Earley S, Heppner TJ, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. TRPV4 forms a novel Ca2+ signaling complex with ryanodine receptors and BKCa channels. Circ Res. 2005;97:1270–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000194321.60300.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]