Abstract

Context:

Carcinoid tumors represent a group of well-differentiated tumors originating from the diffuse endocrine system outside the pancreas and thyroid. The overall prevalence of carcinoid tumors in the United States is estimated to be one to two cases per 100,000 persons. Various sites of origin of this neoplasm are appendix - 30-45%, small bowel - 25-35% (duodenum 2%, jejunum 7%, ileum 91%, multiple sites 15-35%), rectum 10-15%, caecum - 5%, and stomach - 0.5%. Liver metastases from jejunal and ileal carcinoids are generally hypervascular.

Case report:

Here we report a case of primary jejunal carcinoid tumor in a 66-year-old woman metastasizing to liver with ultrasonography, computed tomography, and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DWI) findings.

Conclusion:

Primary jejunal carcinoid tumor is a rare entity. DWI can help in the differential diagnosis of hepatic hypervascular metastatic mass lesions from benign ones, as well as in the diagnosis of carcinoid tumor.

Keywords: Carcinoid, metastases, small bowel, jejunum, diffusion weighted MRI

Introduction

Carcinoid tumors represent a group of well-differentiated tumors originating from the diffuse endocrine system outside the pancreas and thyroid. The overall prevalence of carcinoid tumors in the United States is estimated to be one to two cases per 100,000 persons[1,2]. Carcinoids most frequently occur in the gastrointestinal tract (66.9%), followed by the tracheobronchial system (24.5%). In rare cases, they may arise in the liver, gallbladder, ovary, testis, and thymus[3]. At the time of diagnosis, 58%-64% of patients with small intestinal carcinoids have disease that has spread beyond the intestine to regional lymph nodes or the liver[4].

Here we report a rare case of jejunal carcinoid tumor metastasizing to liver with ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DWI) findings.

Case Report

A 66-year-old woman presented our hospital with complaints of hematochesia and melena. Physical examination revealed hepatomegaly and a mass alining from right upper quadrant to epigastrium. On laboratory examinations blood analysis revealed deep anemia (hemoglobin: 3.6; red blood cell: 2.34), and blood transfusion was induced to the patient.

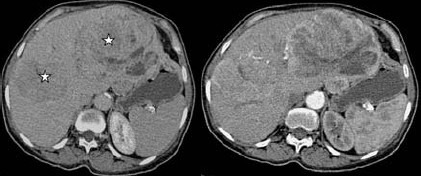

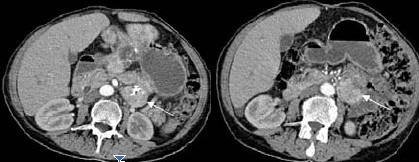

On abdominal US, hepatic echogenous mass lesions the biggest being 14x10cm in size having cystic components were demonstrated. Also a 5×4cm hypoechoic mass lesion neighboring to pancreatic tail protruding into the lumen from the jejunal wall was noted, which contained calcifications. Abdominal CT revealed heterogeneously enhancing hepatic mass lesions having central necrotic areas and a lobulated contour (Fig. 1a, b), and a heterogenously enhancing jejunal mass lesion having calcified areas (Fig. 2). With these radiological findings, a presumptive diagnosis of jejunal carcinoid tumor and hepatic metastases was made.

Fig. 1.

Pre (a) and post contrast (b) CT images reveal peripherally enhancing liver masses (stars) with central necrotic areas.

Fig. 2.

Abdominal contrast enhanced CT images reveal heterogeneously enhancing proximal jejunal mass (carcinoid tumor, arrows) with central calcifications.

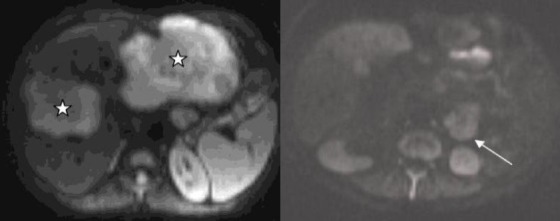

On the other hand, DWI was performed for the differential diagnosis of hepatic masses from cavernous hemangiomas, which revealed restriction in diffusion and an apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value of 1,33×10—3 which was compatible with the ADC values of hepatic metastatic lesions [20] (Fig. 3). The jejunal mass was also displaying restriction in diffusion. US-guided tru-cut biopsy of the biggest hepatic mass lesion was evaluated as carcinoid tumor metastasis histopathologically.

Fig. 3.

The metastatic liver lesions (stars) and the primary jejunal carcinoid tumor (arrow) show restriction (hyperintense signal) on diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging.

Discussion

Gastrointestinal carcinoid is the most common primary tumor of the small bowel and mesentery. It accounts for more than 95% of all carcinoids and 1.5% of all gastrointestinal tumors. The tumor arises from the endochromaffin cells of Kulchitsky i.e. neural crest cells situated at the base of crypts of Lieberkuhn. Various sites of origin of this neoplasm are appendix - 30-45%, small bowel - 25-35% (duodenum 2%, jejunum 7%, ileum 91%, multiple sites 15-35%), rectum 10-15%, caecum - 5%, and stomach - 0.5%. Carcinoids can also rarely occur in pancreas, biliary tract, esophagus and liver[1,2]. The sex prediction for the tumor is M: F: 2:1. Most carcinoids occur in patients older than 50 years, however, appendiceal carcinoids occur in young patients in their second to fourth decade. Most patients are asymptomatic but symptoms can vary from pain, intestinal obstruction (19%), weight loss (16%), palpable mass (14%), intussusceptions, perforation, or gastrointestinal hemorrhage (rare). Carcinoids of the jejunum and ileum occur equally in men and women at a mean age of 65,4 years[1–4]. Our patient was 66 years old, compatible with the literature, and presented with symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding that is quite rare in case of carcinoid tumor.

The majority of jejunal and ileal carcinoids are argentaffin-positive, serotonin-producing, and substance P containing EC-cell tumors that produce carcinoid syndrome when liver or retroperitoneal nodal metastases are present. Similar to all carcinoids, those that are primary to the jejunum and ileum vary in their biologic behavior and ability to metastasize. In general, EC-cell carcinoids of the small intestine behave in a malignant fashion, producing lymph node and liver metastases[1].

The primary tumor is small however it frequently evolves a fibrotic reaction with foreshortening and thickening of the mesentery. The tumor also elaborates serotonin and other histamine-like substances than can cause carcinoid syndrome which is characterized by abdominal cramps, diarrhea, hepatomegaly, flushing etc. Carcinoids also have the tendency to metastasize to lymph nodes, liver and rarely bone[5,6].

The primary tumor is small, slow growing and is rarely demonstrated radiologically. The diagnosis is made when the tumor has spread through the bowel wall into the peritoneum and mesentery and is achieved by several complementary imaging techniques. Plain abdominal scenogram is the initial screening modality and it may show curvilinear calcification. However, it is highly non-specific. Barium studies (enteroclysis, follow through examination) may show intramural or intraluminal filling defects in the distended ileum. There can also be narrowing of the lumen with stricture formation, thickening of the valvulae conniventes and increase in the interbowel loop distance due to wall thickening. Kinking of the small bowel on barium studies is considered the hallmark of carcinoid. Further, tumor spread to the root of mesentery may encase the vessels and produce infarction. Sonography of the bowel can depict pseudokidney sign due to wall thickening, associated lymphadenopathy and liver metastasis[6].

However, the findings are non-specific to offer a confident diagnosis. Diagnosis can be made fairly confidently on CT, which is used for demonstrating the intestine, mesentery, lymph nodes and liver in a single examination and for staging the neoplasm as well as follow up after surgery or chemotherapy. It reveals a soft density mass with speculated borders and radiating strands with or without calcification in 80% of cases[5–8]. In our patient, US revealed wall thickening and calcification in the proximal jejunum, as well as liver masses, and CT demonstrated jejunal and hepatic masses obviously. Other findings on CT can be lymphadenopathy (retroperitoneal, retrocrural) and metastasis commonly to the liver. Metastases are frequent from a midgut primary tumor and rare from appendiceal carcinoid. They also depend on size of the primary tumor: tumors smaller than one cm metastasize in two percent of cases, tumors 1-2 cm metastasize in 50% and >2cm are clinically silent but they may produce carcinoid syndrome. On CT, hepatic metastases are hypervascular enhancing lesions and may assume variety of patterns such as finely nodular, coarsely nodular, mixed single large mass and rarely, pseudocystic appearance probably due to ischemic necrosis[9]. Liver metastases from jejunal and ileal carcinoids are generally hypervascular and as such are generally best seen during the arterial phase of intravenous contrast material administration on CT and MR images. Centrally located tumor necrosis and degeneration may produce central nonenhancing regions within the metastases on CT and MR images, producing a rimlike pattern of enhancement[6,9]. The hepatic masses in our patient were also hypervascular, with cystic changes in the tumor located on the left hepatic lobe. For the differential diagnosis of hepatic lesions, we considered hemangioma and performed DWI with ADC mapping. The ADC value obtained from the hepatic mass was 1.33 × 10-3, supporting metastasis. In a study[5], the mean ADC of hemangioma (7.58 × l0-3 mm2/sec ± 1.88) was the highest, followed by HCC (3.15 × l0-3 mm2/sec ± 1.80) and metastasis (2.55 × l0-3 mm2/sec ± 1.65). We also performed US-guided tru-cut biopsy to the mass on the right hepatic lobe, which was evaluated as carcinoid tumor metastasis histopathologically.

Bone metastases are rare and most osseous metastases have been reported from carcinoid of the stomach and rectum. Mostly they are osteoblastic but rarely, lytic or mixed lesions occur. Carcinoid tumors may also be associated with a high incidence of other primary malignant neoplasms e.g. in the colon, breast, pancreas, kidney, lip, vulva, cervix, larynx, rectosigmoid and histiocytic lymphoma[10].

The imaging appearance of jejunal and ileal carcinoids varies by tumor size, extent of mesenteric involvement, and presence or absence of lymph node or liver metastases. Small, polypoid and nodular carcinoids located in the mucosa and submucosa of the intestinal wall are best evaluated with enteroclysis or small bowel series. In many cases, small nodular carcinoids may be very difficult to detect with a conventional small bowel series. When identified, they are characteristically solitary or multifocal, smooth, rounded nodules or mucosal elevations in the distal ileum[4]. Similarly, small primary tumors may be difficult to visualize with magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. They are best visualized on gadolinium enhanced T1-weighted MR images obtained with fat suppression, where they manifest as nodules or focal areas of mural thickening with moderately intense gadolinium enhancement[11]. The primary tumor may also manifest on CT scans as asymmetric or concentric mural thickening. Mural thickening is secondary to infiltrating tumor and desmoplastic submucosal fibrosis, which thickens and stiffens the intestinal wall, producing mural and irregular fold thickening[12]. In our patient, the jejunal mass was observed as irregular wall thickening.

At the time of diagnosis, 58%–64% of patients with small intestinal carcinoids have disease that has spread beyond the intestine to regional lymph nodes or the liver[4]. Calcification is detected in 70% of mesenteric lymph node metastases[13]. In our patient, hepatic metastases were accompanying the primary jejunal carcinoid tumor at the time of diagnosis.

The imaging differential diagnosis for small intestinal carcinoids includes metastatic disease, primary small intestinal adenocarcinomas, lymphoma, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. The characteristic curvature of the small intestine and spiculated margins of the mesenteric nodal metastases strongly suggest carcinoid. In cases without the characteristic fibrotic changes, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy or biopsy will help in establishing the diagnosis. Nonneoplastic diseases such as Crohn's disease and localized ischemic enteritis may produce inflammatory changes in the distal ileum and mesentery that simulate carcinoid[11,14–18].

Conclusion

Primary jejunal carcinoid tumor is a rare entity. DWI and ADC values can help in the differential diagnosis of hepatic hypervascular metastatic mass lesions from benign ones, as well as in the diagnosis of carcinoid tumor.

References

- 1.Godwin JD., 2nd Carcinoid tumors.An analysis of 2,837 cases. Cancer. 1975;36(2):560–569. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197508)36:2<560::aid-cncr2820360235>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Modlin IM, Sandor A. An analysis of 8305 cases of carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 1997;79(4):813–829. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970215)79:4<813::aid-cncr19>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97(4):934–959. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maglinte DDT, Herlinger H. Small bowel neoplasms. In: Herlinger H, Maglinte DDT, Birnbaum BA, editors. Clinical imaging of the small intestine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 1999. pp. 377–438. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ichikawa T, Haradome H, Hachiya J, Nitatori T, Araki T. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging with a single-shot echoplanar sequence: detection and characterization of focal hepatic lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170(2):397–402. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.2.9456953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolan DJ. The Small Intestine. In: Grainger, Allison, editors. Diagnostic Radiology. 4th ed. London: Churchill Livingston; 2001. pp. 1075–1099. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sweeney JF, Rosemurgy AS. Carcinoid tumors of the gut. Cancer Control. 1997;4(1):18–24. doi: 10.1177/107327489700400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akerström G, Hellman P, Hessman O, Osmak L. Management of midgut carcinoids. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89(3):161–169. doi: 10.1002/jso.20188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dent GA, Feldman JM. Pseudocystic liver metastases in patients with carcinoid tumors: Report of three cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1984;82(3):275–279. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/82.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barclay TH, Schapira DV. Malignant tumors of the small intestine. Cancer. 1983;51(5):878–881. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830301)51:5<878::aid-cncr2820510521>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bader TR, Semelka RC, Chiu VC, Armao DM, Woosley JT. MRI of carcinoid tumors: spectrum of appearances in the gastrointestinal tract and liver. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;14(3):261–269. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payne-James JJ, de Gara CJ, Lovell D, Misiewicz JJ, Gow NM. Metastatic carcinoid tumour in association with small bowel ischaemia and infarction. J R Soc Med. 1990;83(1):54. doi: 10.1177/014107689008300124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pantongrag-Brown L, Buetow PC, Carr NJ, Lichtenstein JE, Buck JL. Calcification and fibrosis in mesenteric carcinoid tumor: CT findings and pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164(2):387–391. doi: 10.2214/ajr.164.2.7839976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelage JP, Soyer P, Boudiaf M, Brocheriou-Spelle I, Dufresne AC, Coumbaras J, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the abdomen: CT features. Abdom Imaging. 1999;24(3):240–245. doi: 10.1007/s002619900488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horton KM, Kamel I, Hofmann L, Fishman EK. Carcinoid tumors of the small bowel: a multitechnique imaging approach. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(3):559–567. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.3.1820559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Vries H, Verschueren RC, Willemse PH, Kema IP, de Vries EG. Diagnostic, surgical and medical aspect of the midgut carcinoids. Cancer Treat Rev. 2002;28(1):11–25. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2001.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bayraktar Y, Kadayıfçı A, Özenç A, Kayhan B, Özdemir A, Küçükali T, et al. Analysis of 23 patients with carcinoid tumors: Emphasis on the relationship between carcinoid syndrome and liver involvement. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Res. 1993;11(3):120–125. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakız D, Coşkun H, Mihmanlı M. Carcinoid tumors of the small bowel. Turkiye Klinikleri J Surg Med Sci. 2005;1(8):57–62. [Google Scholar]