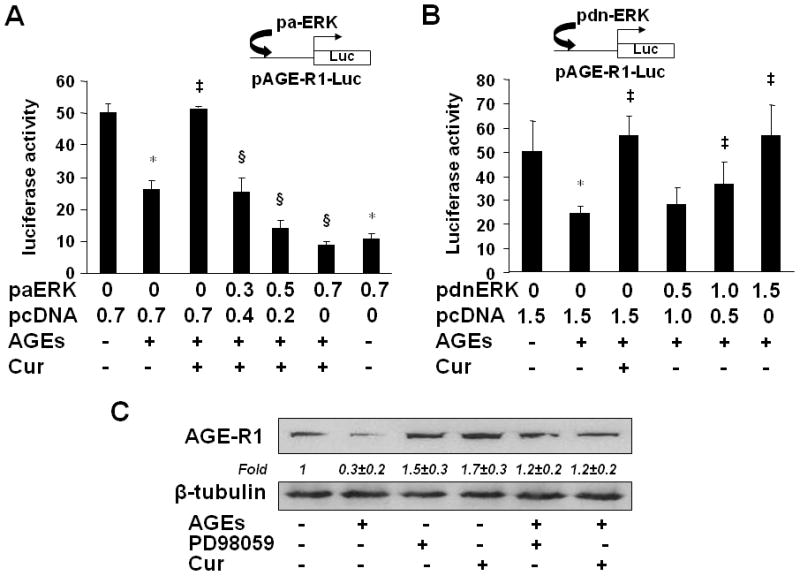

Figure 5. The alterations in the activity of ERK resulted in the changes in the gene promoter activity and the abundance of AGE-R1 in cultured HSCs.

(A & B) HSCs were co-transfected with the AGE-R1 promoter luciferase reporter plasmid pAGE-R1-Luc and the cDNA expression plasmid pa-ERK encoding constitutively active ERK (A), or pdn-ERK encoding dominant negative ERK (B), at indicated doses. After recovery, cells were serum-starved for 4 hr prior to the treatment with or without AGEs (100 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of curcumin (20 μM) in serum-depleted media for additional 24 hr. Luciferase activity assays were conducted (n=6). *p<0.05 vs. cells with no treatment (the 1st column). ‡p<0.05 vs. cells treated with AGEs alone (the 2nd column). §p<0.05 vs. cells treated with AGEs plus curcumin (the 3rd column). The floating schema denoted the plasmids pAGE-R1-Luc and pa-ERK, or pdn-ERK in use for co-transfection.

(C) Serum-starved HSCs were treated with AGEs (100 μg/ml) in the presence of curcumin (20 μM), or the ERK selective inhibitor PD98059 (10 μM), in serum-depleted media for 24 hr. Western blotting analyses were conducted. β-tubulin was used as an internal control for equal loading. Representatives were from three independent experiments. Italic numbers beneath blots were fold changes (mean ± s. d., n=3) in the densities of the bands compared with the control without treatment in the blot, after normalization with the internal invariable control.