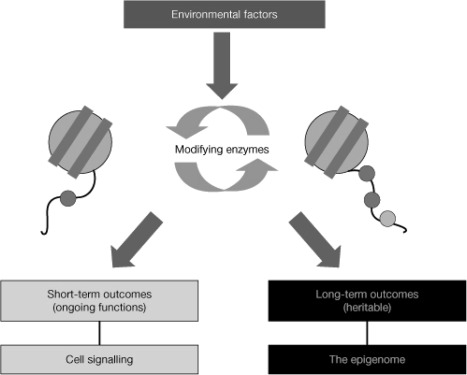

Fig. 5.

Histone modifications can generate both short-term and long-term outcomes. The amino-terminal tails of all eight core histones protrude through the DNA and are exposed on the nucleosome surface, where they are subject to an enormous range of enzyme-catalyzed modifications of specific amino-acid side chains, including acetylation of lysines, methylation of lysines and arginines, and phosphorylation of serines and threonines. Histone tail modifications are put in place by modifying and demodifying enzymes whose activities can be modulated by environmental and intrinsic signals. Modifications may function in short-term, ongoing processes (such as transcription, DNA replication, and repair) and in more long-term functions (as determinants of chromatin conformation, for example heterochromatin formation, or as heritable markers that both predict and are necessary for future changes in transcription). Short-term modifications are transient and show rapidly fluctuating levels. Long-term, heritable modifications need not necessarily be static; in theory, they still show enzyme-catalyzed turnover, but the steady-state level must be relatively consistent. [Reprinted with permission from B. M. Turner: Nat Cell Biol 9:2–6, 2007 (562). © 2007 Macmillan Publishers Ltd.]