Abstract

Purpose

Psychometric scales often change over time, complicating comparison of scores across different versions. The Impact of Cancer (IOC) scale was developed to measure quality of life of long-term cancer survivors. We sought to develop a method for scoring the earlier version, IOCv1, to obtain scores comparable to IOCv2, which is the recommended version.

Methods

Data from 1828 cancer survivors who had completed a questionnaire including all IOCv1 and IOCv2 items were randomly split into training, validation and test sets. The training and validation sets were used to develop and validate linear regression models for predicting each IOCv2 item missing from IOCv1. The models were then applied to the test set to obtain pseudo-IOCv2 scores, which were compared to observed scores to assess predictive performance of the models in independent data.

Results

Observed and pseudo-IOCv2 scale scores were highly correlated in the test sample and had mean differences near zero. The models performed especially well in predicting summary scale scores, with correlations exceeding 0.98.

Conclusions

The approach facilitates comparison across samples of survivors surveyed using different versions of the IOC and may be useful to other investigators trying to compare participants surveyed using different versions of the same instrument.

Keywords: impact of cancer, oncology, psychometric scales, quality of life, cancer survivorship

INTRODUCTION

Psychometric scales are critical tools for measuring quality of life outcomes. Through a process of feedback and refinement, psychometric scales often change over time, with items and multi-item scales being added, deleted or modified. While this process yields improved instruments, it also creates the problem of comparing scores across different versions of the scale.

The Impact of Cancer (IOC) [1–4] is an example of a psychometric scale that has evolved over time. The IOC was developed specifically to measure psychosocial aspects of long-term (more than 5 years post-diagnosis) cancer survivorship not captured by other health-related quality of life instruments. An initial scaling of the IOC was conducted using data collected from 193 long-term cancer survivors. These analyses yielded the IOC version 1 (IOCv1), which included 10 subscales measured by 41 items, as well as positive and negative summary scales [3; 4]. Due to the small sample size, factor analyses were conducted using a priori domains. A more comprehensive scaling of the IOC was conducted several years later with a sample of 1,188 long-term survivors. This scaling process involved de novo factor analysis without a priori domains as well as split-sample cross-validation and evaluation of construct and concurrent validity. This yielded the IOC version 2 (IOCv2), with eight subscales measured by 37 items, as well as positive and negative summary scales [1; 2].

Since the IOCv2 underwent more rigorous psychometric development, it is recommended that it be used rather than IOCv1. However, by the time of publication of IOCv2, studies had already been undertaken using IOCv1 [4–9], and this earlier version may continue to be used. Since IOCv2 is the recommended version, studies that have administered IOCv1 to participants may wish to score the instrument so as to obtain scores comparable to IOCv2 scores. Such “pseudo-IOCv2” scores may facilitate comparison with other cancer survivor samples surveyed using the IOCv2.

Our objective was to develop and test models for obtaining pseudo-IOCv2 scores using only IOCv1 responses.

METHODS

Overview

We used data collected from long-term breast cancer (n=1176) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=652) survivors. Both samples had completed a questionnaire that included all items used in both the IOCv1 and IOCv2, described in [3]. Hence it was possible to compute both IOCv1 and IOCv2 scores for these participants. Our goal was to develop predictive models that utilized as input only IOCv1 item responses to obtain pseudo-IOCv2 scores that closely matched participants’ observed IOCv2 scores.

Participants

The breast cancer survivors were participants in the Life After Cancer Epidemiology (LACE) Study, a prospective cohort study of early-stage breast cancer survivors [10]. The cohort consists of women diagnosed from age 18 to 79 years with a first primary breast cancer (Stage I ≥ 1 cm, II or IIA) recruited primarily from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Cancer Registry and the Utah Cancer Registry. Demographic, treatment and medical characteristics of this sample are described in Crespi et al [1]. Twelve participants included in Crespi et al [1] were subsequently found to have had recurrences and were excluded from the current sample, reducing the sample size from 1,188 to 1,176. The LACE participants were mailed the self-administered questionnaire of IOC items as part of a resurvey wave.

The non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors were identified through the Duke University and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Lineberger tumor registries as previously described [11]. Patients were eligible if diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, ≥19 years old at diagnosis, and ≥2 years post-diagnosis. Characteristics of this sample are described in Crespi et al [2]. These participants were mailed the self-administered questionnaire of IOC items as part of a cross-sectional survey.

Since the IOC is intended to apply to cancer survivors rather than individuals with active disease, respondents with active disease or unknown recurrence status were excluded from the analysis. Both studies were approved by human subjects review boards and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

IOC items are presented as statements regarding specific impacts of cancer to which respondents indicate their level of agreement from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). IOCv1 uses 41 of these items; IOCv2 uses 37 items, some of which are on IOCv1 and some of which are not. IOCv2 also includes employment and relationship scales not considered here.

The 37 items on IOCv2 are used to compute 8 subscale scores and 2 summary scores. Subscale scores are computed as the mean of items comprising the subscale. The IOCv2 Positive Impact Summary scale is scored as the mean of the items on the Altruism/Empathy, Health Awareness, Meaning of Cancer and Positive Self-Evaluation subscales. The IOCv2 Negative Impact Summary scale is scored as the mean of the items on the Appearance Concerns, Body Change Concerns, Life Interferences and Worry subscales.

Statistical Analysis

The combined sample of 1828 survivors was randomly divided into training, validation and test sets using an approximate 50%/30%/20% split (n’s of 927, 509 and 392, respectively). We obtained a predictive linear regression model for each IOCv2 item missing from IOCv1 using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) method [12; 13] for model selection on the training set, implemented in the GLMSELECT procedure in SAS 9.2. The LASSO is a shrinkage and selection method for linear regression that minimizes the sum of squared errors with a bound on the sum of the absolute values of the coefficients as a protection against overfitting. Each IOCv2 item response targeted for prediction was used as a dependent variable and all IOCv1 item responses were included in the potential predictor pool. Average squared error for the validation data was used as the criterion for choosing among models at each step of the LASSO algorithm.

The test set was used to assess the predictive performance of the selected models on independent data not used in model selection. For participants in the test set, the selected models were used to compute pseudo-responses for IOCv2 items missing from IOCv1. These pseudo-IOCv2 item responses were used to compute pseudo-IOCv2 scale scores, computed as the mean of items comprising the scale but using pseudo-IOCv2 item responses for items not in the IOCv1 where applicable. Predictive performance was assessed by examining the distribution of differences between observed and pseudo-IOCv2 scale scores and the Pearson correlation between them.

RESULTS

Table 1 lists the IOCv2 scales and indicates the number of items in each scale that are included or missing from IOCv1. In total, IOCv2 uses 37 items to form 8 subscales and 2 summary scales; 30 of these items are also included in IOCv1, and 7 are not and thus were targeted for prediction. The Life Interferences subscale had the highest level of missingness, with 57% (4/7) of its items not in IOCv1. Three other subscales were missing only single items. The Negative Impact summary scale had more items missing than the Positive Impact summary scale (25%, 5/20 compared to 12%, 2/17).

Table 1.

Comparison of item content of IOCv1 and IOCv2

| Total items in IOCv2 scale | Number in IOCv1 | Number not in IOCv1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| IOCv2 Subscales | |||

| Altruism/Empathy | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Health Awareness | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Meaning of Cancer | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Positive Self-Evaluation | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Appearance Concerns | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Body Change Concerns | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Life Interferences | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| Worry | 7 | 6 | 1 |

|

| |||

| IOCv2 Summary Scales | |||

|

| |||

| Positive Impact Summary | 17 | 15 | 2 |

| Negative Impact Summary | 20 | 15 | 5 |

|

| |||

| Total | 37 | 30 | 7 |

The LASSO algorithm selected models with 5–9 predictors for each IOCv2 item targeted for prediction (Appendix A). Table 2 summarizes the performance of model selection in terms of the average squared error of prediction of the selected models in the training, validation and test sets for each of the seven predicted items. The average squared errors were comparable across sets, supporting the generalizability of the models to independent data.

APPENDIX A.

Regression coefficients to be used to compute IOCv2 pseudo-item responses from IOCv1 items

| Predictor | Regression coefficients by missingIOCv2item: IOCv2 number† (IOC number†) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOCv1 number† | IOC number† | Item wording | 12 (23) | 5 (32) | 37 (58) | 27 (57) | 28 (67) | 29 (68) | 30 (70) |

| Intercept | 0.594 | 2.798 | 0.603 | 0.857 | 1.178 | 1.126 | 1.246 | ||

| 2 | 8 | Having had cancer makes me feel unsure about my future | 0.125 | 0.012 | 0.017 | 0.024 | |||

| 3 | 9 | I worry about my future | −0.007 | 0.097 | |||||

| 5 | 12 | I feel like time in my life is running out | 0.028 | −0.010 | |||||

| 7 | 14 | Having had cancer has strengthened my religious faith or sense of spirituality | 0.018 | ||||||

| 11 | 19 | I worry about my health | 0.100 | ||||||

| 12 | 21 | I worry about the cancer coming back or about getting another cancer | 0.175 | ||||||

| 13 | 22 | New symptoms make me worry about the cancer coming back | 0.262 | 0.035 | 0.015 | ||||

| 15 | 25 | I am bothered that my body cannot do what it could before having had cancer | 0.043 | 0.021 | |||||

| 17 | 27 | I feel disfigured | 0.018 | 0.017 | |||||

| 20 | 30 | Having to pay attention to my physical health interferes with my life | 0.059 | 0.012 | 0.060 | ||||

| 21 | 33 | I feel a sense of pride or accomplishment from surviving cancer | 0.356 | ||||||

| 22 | 34 | I learned something about myself because of having had cancer | 0.058 | ||||||

| 23 | 35 | I am angry about having had cancer | 0.123 | 0.048 | |||||

| 24 | 36 | I feel guilty for somehow being responsible for getting cancer | −0.036 | 0.070 | |||||

| 25 | 37 | I feel that I am a role model to other people with cancer | 0.020 | ||||||

| 26 | 39 | Having had cancer has made me feel old | 0.057 | 0.087 | 0.088 | 0.016 | |||

| 27 | 40 | I feel guilty today for not having been available to my family when I had cancer | 0.035 | 0.013 | 0.036 | 0.120 | |||

| 28 | 43 | Having had cancer has been the most difficult experience in my life | 0.059 | ||||||

| 32 | 54 | Because of cancer I have become better about expressing what I want | 0.115 | ||||||

| 33 | 55 | Because of cancer I have more confidence in myself | 0.299 | ||||||

| 34 | 56 | Having had cancer has given me direction in life | 0.238 | ||||||

| 39 | 65 | I feel that I should give something back to others because I survived cancer | 0.024 | ||||||

| 40 | 72 | Having had cancer keeps me from doing activities I enjoy | −0.062 | 0.262 | |||||

| 41 | 73 | Ongoing cancer-or treatment-related symptoms interfere with my life | 0.050 | 0.038 | 0.106 | ||||

“IOC” numbering corresponds to item numbers in Appendix A of Zebrack et al [3]; “IOCv1” numbering refers to order in the IOCv1 instrument; “IOCv2” numbering refers to numbering in the IOCv2 instrument.

Table 2.

Comparison of average squared error of prediction of the selected models in the training, validation and test sets

| Item number | Item wording | Average squared error | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOC | IOCv2 | Training set | Validation set | Test set | |

| 23 | 12 | Having had cancer makes me feel uncertain about my health | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.41 |

| 32 | 5 | I consider myself to be a cancer survivor | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.50 |

| 58 | 37 | Because of having had cancer I feel that I have more control of my life | 0.68 | 0.57 | 0.67 |

| 57 | 27 | I feel like cancer runs my life | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| 67 | 28 | Having had cancer has made me feel alone | 0.66 | 0.57 | 0.58 |

| 68 | 29 | Having had cancer has made me feel like some people do not understand me | 0.78 | 0.70 | 0.69 |

| 70 | 30 | Uncertainty about my future affects my decisions to make plans | 1.22 | 1.36 | 1.20 |

“IOC” numbering corresponds to item numbers in Appendix A of Zebrack et al [3]; “IOCv2” numbering refers to numbering in the IOCv2 instrument.

Table 3 compares observed and pseudo-IOCv2 scores in the test set, for IOCv2 scales with missing items. In all cases, the mean difference between observed and pseudo-scores was near zero, and the standard deviation of the differences was less than 0.33, and more typically less than 0.18. The correlations indicated close agreement, especially for the summary scales, in both survivor groups and overall. The Life Interferences subscale was predicted the least accurately, but still had correlation of 0.896 in the overall test sample.

Table 3.

Comparison of observed and pseudo-IOCv2 scores in the test set (N = 392)

| IOCv2 Scale | Observed IOCv2 score | Pseudo- IOCv2 score | Difference: Mean ± SD (min, max) | r, total test sample (N = 392) | r, breast cancer survivors in test sample (N = 253) | r, non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors in test sample (N = 139) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meaning of Cancer subscale | 2.93 ± 0.92 | 2.93 ± 0.88 | 0.006 ± 0.153 (−0.42, 0.69) | 0.986 | 0.984 | 0.989 |

| Positive Self-Evaluation subscale | 3.90 ± 0.79 | 3.90 ± 0.74 | −0.002 ± 0.172 (−0.68, 0.58) | 0.976 | 0.978 | 0.976 |

| Life Interferences subscale | 1.97 ± 0.66 | 1.95 ± 0.44 | 0.021 ± 0.329 (−0.65, 1.31) | 0.896 | 0.920 | 0.864 |

| Worry subscale | 2.74 ± 0.90 | 2.72 ± 0.87 | 0.011 ± 0.010 (−0.29, 0.39) | 0.994 | 0.994 | 0.995 |

| Positive Impact Summary scale | 3.52 ± 0.65 | 3.52 ± 0.64 | 0.001 ± 0.061 (−0.17, 0.20) | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 |

| Negative Impact Summary scale | 2.38 ± 0.71 | 2.37 ± 0.64 | 0.010 ± 0.128 (−0.27, 0.48) | 0.988 | 0.988 | 0.988 |

CONCLUSION

We have developed models for obtaining pseudo-IOCv2 scale scores from IOCv1 responses that may facilitate comparison of quality of life impacts across samples of survivors surveyed using different versions of the IOC. The models had very good predictive performance in an independent test sample.

The regression models for obtaining pseudo-IOCv2 item responses are provided in Appendix A, and Appendix B provides an example of the calculations. A SAS macro for computing pseudo-IOCv2 scale scores is available from the first author.

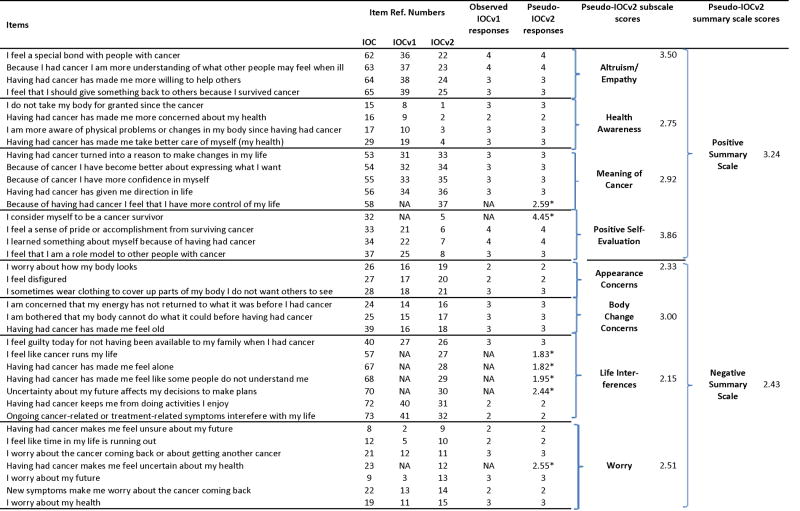

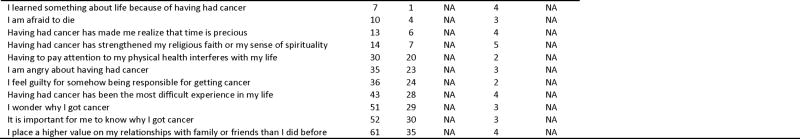

APPENDIX B.

Example of calculation of pseudo-IOCv2 item responses, subscale and summary scores for one respondent

|

|

“IOC” numbering corresponds to item numbers in Appendix A of Zebrack et al [3]; “IOCv1” numbering refers to order in the IOCv1 instrument; “IOCv2” numbering refers to numbering in the IOCv2 instrument.

Predicted values of item responses obtained using regression equations in Appendix A.

Limitations must be acknowledged. The respondents completed an 81-item questionnaire rather than the shorter IOCv1 or IOCv2, and responses may have differed from what would have been obtained from the IOCv1 or IOCv2 due to the different context; in particular, similarity of item responses may have been enhanced. The sample was limited to breast cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors and the models may not perform as well for individuals with other diagnoses.

Overall, the predictive performance of the models together with the substantial overlap between IOCv1 and IOCv2 suggests that investigators can use pseudo-IOCv2 scores with confidence that they are comparable to actual IOCv2 scores. Our approach may be useful to other investigators seeking to compare participant samples surveyed using different versions of the same scale.

Acknowledgments

Crespi was supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA16042. Smith was supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA101492. We appreciated the assistance of Sheng Wu with creating the SAS macro.

Abbreviations

- IOC

Impact of cancer

Footnotes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Crespi CM, Ganz PA, Petersen L, Castillo A, Caan B. Refinement and Psychometric Evaluation of the Impact of Cancer Scale. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100(21):1530–1541. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crespi CM, Smith SK, Petersen L, Zimmerman S, Ganz PA. Measuring the impact of cancer: a comparison of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and breast cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2010;4(1):45–58. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0106-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zebrack BJ, Ganz PA, Bernaards CA, Petersen L, Abraham L. Assessing the impact of cancer: Development of a new instrument for long-term survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(5):407–421. doi: 10.1002/pon.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zebrack BJ, Yi J, Petersen L, Ganz PA. The impact of cancer and quality of life for long-term survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17(9):891–900. doi: 10.1002/pon.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gudbergsson SB, Fossa SD, Ganz PA, Zebrack BJ, Dahl AA. The associations between living conditions, demography, and the impact of cancer scale in tumor-free cancer survivors: a NOCWO study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2007;15(11):1309–1318. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0251-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holterhues C, Cornish D, van de Poll-Franse LV, Krekels G, Koedijk F, Kuijpers D, Coebergh JW, Nijsten T. Impact of Melanoma on Patients’ Lives Among 562 Survivors A Dutch Population-Based Study. Archives of Dermatology. 2011;147(2):177–185. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kornblith AB, Mirabeau-Beale K, Lee H, Goodman AK, Penson RT, Pereira L, Matulonis UA. Long-Term Adjustment of Survivors of Ovarian Cancer Treated for Advanced-Stage Disease. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2010;28(5):451–469. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2010.498458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mols F, Holterhues C, Nijsten T, van de Poll-Franse LV. Personality is associated with health status and impact of cancer among melanoma survivors. European Journal of Cancer. 2010;46(3):573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith SK, Zimmerman S, Williams CS, Zebrack BJ. Health Status and Quality of Life Among Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Survivors. Cancer. 2009;115(14):3312–3323. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caan B, Sternfeld B, Gunderson E, Coates A, Quesenberry C, Slattery ML. Life After Cancer Epidemiology (LACE) study: A cohort of early stage breast cancer survivors (United states) Cancer Causes & Control. 2005;16(5):545–556. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-8340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith SK, Zimmerman S, Williams CS, Preisser JS, Clipp EC. Post-traumatic stress outcomes in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(6):934–941. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Methodological. 1996;58(1):267–288. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Efron B, Hastie T, Johnstone I, Tibshirani R. Least angle regression. Annals of Statistics. 2004;32(2):407–451. [Google Scholar]