Abstract

Fibroblastic preadipocyte cells are recruited to differentiate into new adipocytes during the formation and hyperplastic growth of white adipose tissue. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), the master regulator of adipogenesis, is expressed at low levels in preadipocytes, and its levels increase dramatically and rapidly during the differentiation process. However, the mechanisms controlling the dynamic and selective expression of PPARγ in the adipocyte lineage remain largely unknown. We show here that the zinc finger protein Evi1 increases in preadipocytes at the onset of differentiation prior to increases in PPARγ levels. Evi1 expression converts nonadipogenic cells into adipocytes via an increase in the predifferentiation levels of PPARγ2, the adipose-selective isoform of PPARγ. Conversely, loss of Evi1 in preadipocytes blocks the induction of PPARγ2 and suppresses adipocyte differentiation. Evi1 binds with C/EBPβ to regulatory sites in the Pparγ locus at early stages of adipocyte differentiation, coincident with the induction of Pparγ2 expression. These results indicate that Evi1 is a key regulator of adipogenic competency.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a major risk factor for many diseases, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and many cancers (10, 15). Weight gain occurs when energy intake from food chronically exceeds energy expenditure through physical activity and metabolism. Excess energy is stored as triglycerides in adipose tissue, which expands through increases in the size (hypertrophy) and/or number (hyperplasia) of adipocytes. The development and maintenance of an appropriate mass of adipose tissue are crucial for systemic metabolic health because either insufficient or excess tissue leads to insulin resistance and metabolic disease.

New adipocytes are thought to arise from committed populations of fibroblastic cells resident within adipose tissues, so-called preadipocytes (reviewed in reference 6). Recent data show that these adipogenic precursors are intimately associated with the vasculature and express particular cell surface markers (16, 30, 41). Preadipocytes purified from adipose tissue can undergo adipogenic differentiation in culture, but there is substantial cellular heterogeneity within these isolates. Immortal preadipocyte cell lines (e.g., 3T3-L1 and 3T3-F442A cells) derived from mouse embryo fibroblasts undergo a highly conserved and efficient program of adipogenesis in culture and upon transplantation in vivo. These cell lines have provided a powerful and tractable model system to elucidate the transcriptional networks of adipogenesis.

The nuclear hormone receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and members of the C/EBP (CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein) family of transcription factors orchestrate the adipogenic differentiation process. PPARγ is considered to be the “master regulator” of adipose cell differentiation since it is both necessary and sufficient for adipocyte development (1, 31, 42). Genome-wide analyses show that PPARγ binds and regulates a large majority of adipocyte-selective genes (19, 22, 24). Moreover, PPARγ is the molecular target for the thiazolidinedione class of antidiabetic drugs (20). Activation of PPARγ in adipocytes is thought to promote insulin sensitivity by several mechanisms, including (i) increasing lipid storage capacity in adipose tissue (2, 48), (ii) directly inducing the expression of adiponectin, a secreted factor that enhances insulin action in muscle and liver (18, 23), and (iii) promoting the differentiation of preadipocytes (25). Therefore, it is important to define the molecular pathways that control the expression levels of PPARγ in adipocytes.

During the process of adipogenesis, hormonal inducers (a combination of glucocorticoids, insulin, and agents that elevate cyclic AMP [cAMP] levels) raise the levels of C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ in confluent preadipocytes. C/EBPβ and/or C/EBPδ then stimulates the expression of PPARγ (32, 45). However, increased levels of C/EBPβ alone are not sufficient to drive PPARγ expression and adipogenesis (46), suggesting a requirement for other factors. Recently, Gupta et al. found that Zfp423 is expressed at higher levels in preadipocytes than in nonadipogenic fibroblasts, where it acts to control the levels of PPARγ (14). However, the mechanism through which Zfp423 controls PPARγ expression is unclear. Notably, the PPARγ2 isoform is expressed almost exclusively in the adipocyte lineage, whereas PPARγ1 is more broadly expressed. To date, the mechanism for adipose-selective expression of PPARγ2 has not been defined.

In this study, we have uncovered an essential function for the Evi1 isoform of MECOM (for Mds1-Evi1 complex) in the process of adipocyte differentiation. MECOM is a member of the PR (PRDI-BF1 and RIZ homology) domain-containing family of zinc finger transcriptional regulatory proteins and is closely related in sequence and structure to Prdm16. Previous studies revealed that Prdm16 is a key regulator of brown and “beige” fat cell differentiation (17, 33, 34), but Prdm16 is not expressed in all white fat cells. In contrast, we found that MECOM is expressed in all types of white adipocytes and fat depots that we examined. Notably, MECOM levels rise dramatically at the onset of adipogenic differentiation even before the addition of adipogenic inducers. Depletion of MECOM from preadipocytes blocked adipocyte differentiation, whereas ectopic expression of Evi1 drove adipocyte differentiation in nonadipogenic cells. Mechanistic studies showed that Evi1 binds to C/EBPβ and that an Evi1-C/EBPβ transcriptional complex is recruited to regulatory elements in Pparγ2 during the first 2 days of adipocyte differentiation. These results demonstrate that Evi1 determines adipogenic competency, acting, in part, through regulation of C/EBPβ function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

3T3-L1 preadipocytes were passaged at subconfluence in 10% bovine serum (BS) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM); adipogenesis was induced at confluence with induction medium of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in DMEM supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin (P/S), 5 μg/ml insulin, 1 mM dexamethasone, and 500 μM isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX) for 2 days, after which adipocytes were maintained in 10% FBS-DMEM supplemented with P/S. 3T3-F442A cells were treated as were 3T3-L1 cells except that the postinduction maintenance medium included 5 μg/ml insulin. NIH 3T3, 293, and 293T cells were grown in 10% FBS-DMEM and induced to differentiate as adipocytes where required as for 3T3-L1 cells. Transient transfections were done using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Primary cells were isolated from white epididymal or brown interscapular fat tissue based on previous methods (29) from 10-week-old CD-1 mice. Briefly, tissue was digested in DMEM containing 1.5 U/ml collagenase D (Roche) and 2.4 U/ml Dispase II (Roche) for 45 min at 37°C. Digests were passed through 100-μm-pore-size cell strainers and centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min. The floating fraction (adipocytes) was discarded, and the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) pellet containing preadipocytes was resuspended in growth medium. Epididymal growth medium consisted of 60% DMEM/F12 (low glucose)—40% MCDB 201 medium (catalog number M6770; Sigma) supplemented with 2% FBS, 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS), 0.1 mM l-ascorbic acid-2-phosphate, 10 ng/ml fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2), P/S, and primocin (Invivogen); brown adipose tissue (BAT) growth medium consisted of 90% DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, P/S, and primocin. Differentiation was induced with medium containing DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, P/S, 5 μg/ml insulin, 1 μM dexamethasone, 0.5 mM IBMX, 1 nM triiodothyronine (T3), and 125 μM indomethacin.

Retrovirus and lentivirus.

Viruses were produced by 3-plasmid transfection into 293T cells by calcium phosphate (12). Cells were refed 16 to 24 h after transfection with 10% FBS-DMEM; virus-containing medium was harvested after 48 h and filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size syringe filters (Fisher). Target cells were infected overnight with virus mixed with fresh medium and 8 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich). Retrovirus was produced using mouse stem cell virus (MSCV; Clontech) or Super-Retro (Oligoengine) vectors, using vesicular stomatitis virus G (VSV-G) envelope protein. Lentivirus used for short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression was based on the pLKO system (39).

Cell staining.

For Oil Red O staining, cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min, rinsed with PBS, and incubated for several hours with a 60/40 solution of 0.5% Oil-Red-O (Sigma) in 2-propanol–distilled water before cells were rinsed and imaged. For fluorescence staining of lipid, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), washed several times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and incubated for 5 min with PBS, 0.2 μg/ml 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and 0.1 μg/ml Bodipy (4,4-difluoro-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene) 493/503 (Invitrogen) before cells were rinsed with PBS and coverslipped with fluorescence mounting medium (Dako).

RNA isolation.

Cells or tissue samples were homogenized in TRIzol (Invitrogen), and aqueous fractions of RNA were collected following centrifugation after the addition of chloroform. An equal volume of 70% RNase-free ethanol was added, and the resulting solution was processed for total RNA through silica columns (PureLink RNA Mini; Ambion). RNA concentrations were assessed by the optical density at 260 nm (OD260) using a Nanodrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific).

Real-time PCR.

Reverse transcription (RT) reactions were completed using 500 to 1,000 ng of total RNA as input for the High Capacity cDNA RT kit (ABI). PCRs were done in 384-well plates in 8-μl reaction volumes comprised of 4 μl of 2× SYBR Master Mix (ABI, Affymetrix), 0.5 μl (312 nM) of primer mix (IDT), and 3.5 μl of diluted template from an RT reaction or chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) elution (1.75%). Primer sequences can be found in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Protein isolation and Western blotting.

Whole-cell lysates were collected in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete; Roche) and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). After extraction and centrifugal clarification, protein content was assayed with a detergent-compatible (DC) protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). SDS-PAGE was conducted with 30 to 50 μg of total protein using Tris-acetate or bis-Tris NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen). Following protein transfer onto Immobilon P membrane (Millipore), blots were interrogated with anti-Evi1 (sc-8707-R; Santa Cruz), anti-C/EBPβ (sc-150; Santa Cruz), anti-PPARγ (H-100) (sc-7196; Santa Cruz), anti-PPARγ (E-8) (sc-7273; Santa Cruz), and antihemagglutinin (anti-HA; 12CA5) primary antibodies, followed by secondary detection with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated species-specific antibody. HyGlo (Denville) or SuperSignal West Femto (Pierce) enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) was used for HRP detection and recorded with radiography film (GeneMate; Denville Scientific).

Coimmunoprecipitations (co-IPs).

293 cells were transfected with expression plasmids encoding HA-Evi1 (mouse) and/or C/EBPβ (mouse). After 48 h, cells were harvested, and protein complexes were immunoprecipitated with anti-C/EBPβ (sc-150; Santa Cruz) overnight at 4°C. Associated proteins were washed and then eluted in denaturing loading buffer. Following SDS-PAGE and membrane transfer, Western blots were probed with anti-Evi1 (sc-8707-R; Santa Cruz), anti-HA (12CA5), and anti-C/EBPβ (sc-150; Santa Cruz) antibodies as described above.

Co-IPs of endogenous proteins from 3T3-L1 cells were conducted as above, except that nuclear lysates were used. Cells gently homogenized in cold hypotonic buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, Complete protease inhibitor cocktail [PIC; Roche]). Nuclei were pelleted at 2,000 × g at 4°C, rehomogenized in cold extraction buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.6 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 25% [vol/vol] glycerol, PIC) and then placed on a rotating shaker at 4°C for 2 to 3 h before centrifugation at 16,000 × g. The supernatant (nuclear fraction) was diluted with low-salt buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2% Triton, 1 mM EDTA, 25% [vol/vol] glycerol, PIC) and used for subsequent immunoprecipitation with IgG or anti-C/EBPβ.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Cells were rinsed with PBS and fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature before cross-linking was quenched with 125 mM glycine for 5 min. Subsequent solutions included Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Nuclei were isolated prior to lysis in 1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, and 10 mM EDTA. Chromatin was sheared by sonication and diluted; input aliquots were removed, and the remainder was precleared with salmon sperm DNA and protein A-Sepharose beads (CL4B; GE). Protein-DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated with 1.2 μg of antibody overnight at 4°C with normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027; Santa Cruz), anti-Evi1 (sc-8707-R; Santa Cruz), anti-Evi1 (A. Perkins, University of Rochester Medical Center), anti-C/EBPβ (sc-150; Santa Cruz), anti-histone H3 dimethylated at K4 ([H3K4me2] AB32356; Abcam), or anti-histone H3 acetylated at K9 ([H3K9Ac] 17-658; Millipore). Complexes were isolated with protein A-Sepharose beads, washed, and eluted with 1% SDS–0.1 M NaHCO3. Cross-linking was reversed by overnight incubation at 65°C, followed by proteinase K digestion and purification of DNA fragments using PCR purification columns (Qiagen). Eluted DNA was analyzed by real-time PCR on a 7900 machine (ABI) using SYBR green chemistry (ABI, Affymetrix). Target enrichment was calculated as percent input recovered material and normalized to 18S nonspecific background signal. Primer sequences are found in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

Digital imaging.

Scanned films and digital images were processed with Photoshop CS4 (Adobe) using linear adjustments only.

RESULTS

Evi1 expression increases at the onset of adipogenesis.

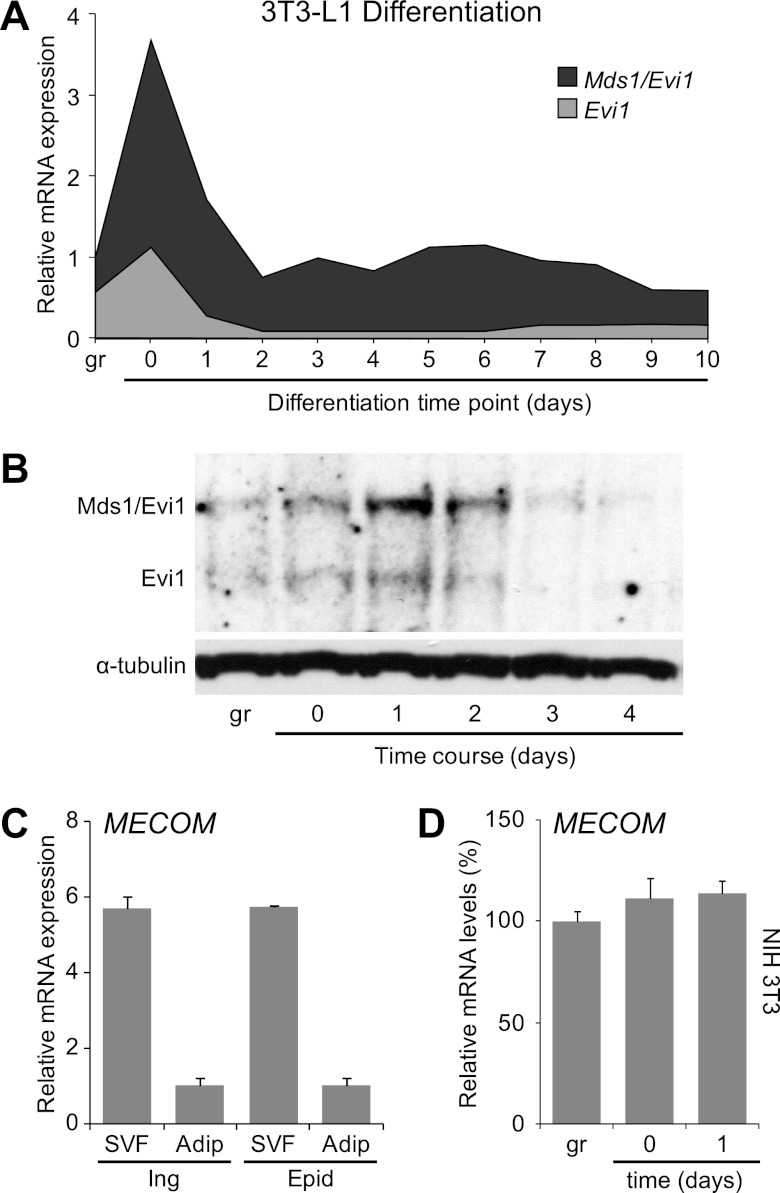

The 3T3-L1 preadipocyte cell line is a standard in vitro model for white adipocyte differentiation, undergoing a stereotyped program of adipocyte differentiation following treatment with proadipogenic hormones (13; reviewed in reference 37).The two major transcripts from the Evi1 locus, Evi1 and Mds1-Evi1 (collectively referred to as MECOM) are dynamically regulated during adipocyte differentiation, with low mRNA levels in growing cells, a peak of expression at confluence and early after hormone induction, and continuing moderate expression at later times of differentiation (Fig. 1A). Consistent with this, Evi1 and Mds1-Evi1 protein expression lags mRNA expression by 12 to 24 h, and both forms are most easily detected within the initial 48 h of adipogenic induction versus subconfluent or well-differentiated cultures (Fig. 1B). In tissue, MECOM expression is predominantly found in the preadipocyte-containing stromal vascular fraction (SVF) rather than in mature adipocytes (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, MECOM levels are specifically increased during the initial stages of adipogenesis only in preadipocytes since cell confluence and/or adipogenic inducers did not stimulate MECOM expression in nonadipogenic NIH 3T3 fibroblasts (Fig. 1D) or in skeletal myoblasts (data not shown). Evi1 transcripts are readily detected in all adipose tissues examined, with higher levels in white adipose tissue (epididymal, inguinal, and retroperitoneal) than in interscapular brown adipose tissue (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These results suggested that the increased Evi1 in early differentiating preadipocytes may be critical to the adipogenic process.

Fig 1.

MECOM is expressed early during adipocyte differentiation. (A) Total MECOM mRNA levels (with Mds1-Evi1 and Evi1 components) at daily time points during a 3T3-L1 differentiation time course. (B) Western blot of total protein from a 3T3-L1 differentiation time course with anti-MECOM antibody that recognizes both the long (Mds1-Evi1) and short (Evi1) protein isoforms. (C and D) MECOM (total Evi1 and Mds1-Evi1) expression in fractionated adipose tissues. SVF, stromovascular fraction; Adip, mature adipocytes; Ing, inguinal; Epid, epididymal. (D) MECOM expression in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts during growth (gr), confluence (day 0), or after hormone induction (day 1). Transcripts were analyzed by real-time PCR and normalized to Tbp.

Evi1 expression induces adipogenesis.

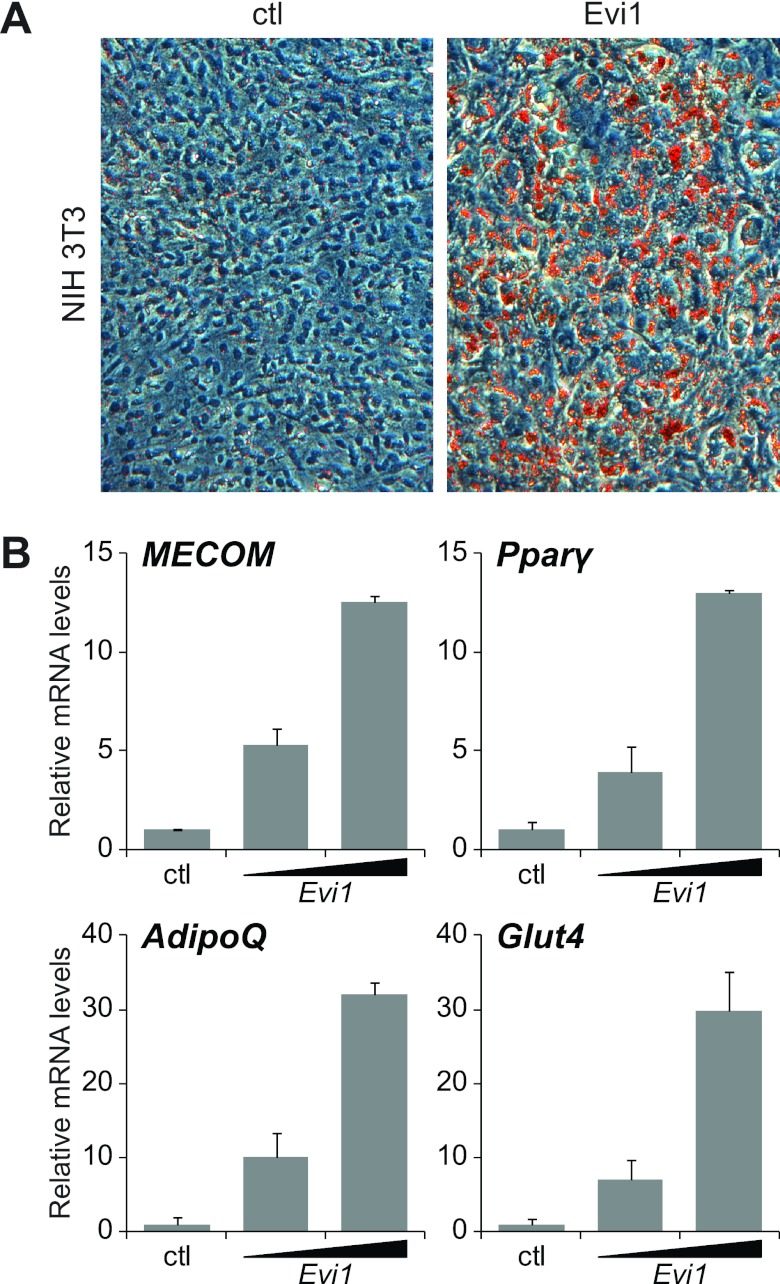

To study the function of Evi1 in adipocyte differentiation, we used a retroviral vector to express Evi1 (or a control vector) in nonadipogenic NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. Evi1 expression produced no apparent phenotype in subconfluent cells. However, upon treatment with adipogenic hormones, only the Evi1-expressing NIH 3T3 cells underwent morphological conversion into adipocytes, as evidenced by the accumulation of lipid droplets that were readily stained with Oil Red O (Fig. 2A). Gene expression analysis after adipogenic induction showed that Evi1 induced the expression of adipocyte-selective genes in a dose-dependent manner, including Pparγ, the adiponectin gene (AdipoQ), and the glucose transporter type 4 gene (Glut4) (Fig. 2B). Adipogenesis in Evi1-expressing NIH 3T3 cells was qualitatively similar but quantitatively less efficient than in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes (Fig. 2A; see also Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). To determine whether Evi1 expression could also convert cells from another lineage into adipocytes, we expressed Evi1 or control vector in C2C12 cells, a committed skeletal myoblast cell line. Strikingly, Evi1-expressing but not control vector-expressing C2C12 cells underwent adipocyte differentiation in response to adipogenic hormones (see Fig. S2). Together, these results indicate that expression of Evi1 can convert nonadipogenic cells into adipocytes.

Fig 2.

Ectopic expression of Evi1 induces adipogenesis. NIH 3T3 fibroblasts were infected with empty (ctl) or Evi1-expressing (Evi1) retrovirus and then cultured for 8 days under adipocyte differentiation conditions. (A) Oil Red O staining of lipid droplets. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of gene expression in NIH 3T3 cells expressing endogenous (ctl) or ectopic (low or high) levels of Evi1, normalized to Tbp expression.

Evi1 is required for adipogenesis.

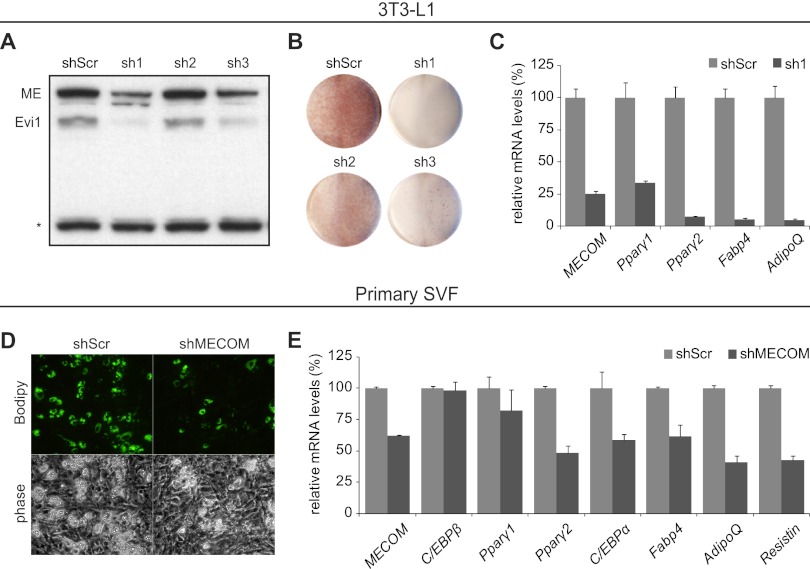

The adipogenic action of Evi1 in fibroblasts prompted us to examine the requirement for Evi1 in adipocyte differentiation using short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated knockdown. First, three different shRNAs (sh1, sh2, and sh3) and a nontargeting scrambled RNA (shScr) were expressed in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes using retroviral vectors prior to the stimulation of differentiation. The target sequences of the shRNAs were common to MECOM transcripts for Evi1 and Mds1-Evi1. Two shRNAs (sh1 and sh3) efficiently depleted Evi1 and Mds1-Evi1 protein levels in confluent 3T3-L1 preadipocytes relative to the nontargeting scrambled shRNA (shScr) or ineffective sh2 (Fig. 3A). In response to adipogenic inducers, control cultures (scr and sh2) underwent efficient morphological differentiation into lipid droplet-containing adipocytes, as revealed by Oil Red O staining (Fig. 3B; see also Fig. S3A in the supplemental material). In contrast, MECOM-depleted 3T3-L1 preadipocytes (sh1 and sh3) did not acquire adipocyte morphology or accumulate lipid droplets when induced to undergo differentiation. Gene expression analysis showed that MECOM-depleted (shMECOM) cultures expressed greatly reduced levels of adipocyte-specific genes after 6 days of differentiation compared to control shScr-expressing cultures. Specifically, Pparγ1, Pparγ2, the fatty acid binding protein 4 gene (Fabp4) mRNA, and AdipoQ were reduced in shMECOM cultures to 10 to 20% of their levels in control (scr) cultures (Fig. 3C). Similarly, reduction of MECOM blocked adipogenesis in 3T3-F442A cells, another immortal preadipocyte line (see Fig. S3B).

Fig 3.

shRNA knockdown of MECOM in 3T3-L1 cells inhibits adipogenesis. (A and C) Control shRNA (shScr; scramble) or one of three shRNAs against MECOM (sh1, sh2, and sh3) was introduced into 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. (A) Western blot with anti-MECOM antibody recognizing both the long (ME, Mds1-Evi1) and short (Evi1) isoforms. The asterisk indicates a nonspecific band showing equal loading of lanes. (B) Oil Red O staining of plates of differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes. (C) Real-time PCR analysis of total RNA from control (shScr) or shMECOM (sh1) lentivirus-infected 3T3-L1 cells after 8 days of differentiation. Expression in shScr, 100%. (D and E) Primary SVF preadipocytes infected with lentiviral shScr or shMECOM viruses and differentiated for 4 days. (D) Bodipy 493/503 staining for lipid droplet accumulation. (E) Real-time PCR analysis for gene expression, normalized to Tbp and relative to shScr.

At the onset of differentiation, 3T3-L1 cells undergo a mitotic clonal expansion (MCE) phase (40). Whereas shScr-expressing cells increased in number by 110% between day 0 and day 2 of differentiation, shMECOM cells showed only a 20% increase (see Fig. S3C). Increasing the cell density of shMECOM cells did not rescue their differentiation deficit (not shown).

The 3T3-L1 line is a robust cellular model of white fat differentiation. However, we also examined the requirement for Evi1 in bona fide preadipocytes isolated from mouse fat tissue. Primary stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells from the epididymal adipose depot were infected with retrovirus expressing shScr or shMECOM, prior to addition of differentiation inducers. Four days after induction, shScr-expressing cultures had undergone robust differentiation into lipid-containing adipocytes, whereas shMECOM-infected cultures were substantially inhibited (Fig. 3D). Molecular analysis confirmed the morphological differences, demonstrating a 40% reduction in MECOM expression that was reflected in similar (40 to 50%) reductions in expression levels of adipocyte-selective genes, such as transcription factor genes Pparγ2 and C/EBPα and differentiation marker genes Fabp4, AdipoQ, and the resistin gene (Fig. 3E). MECOM knockdown in brown preadipocytes did not decrease Pparγ2 and C/EBPα although this was accompanied by an increased level of Prdm16 (see Fig. S3D in the supplemental material). Nonetheless, there remained a substantial deficit in phenotypic differentiation and adipose gene expression (see Fig. S3D and E). Taken together, our knockdown experiments indicate that Evi1 is required for adipocyte differentiation.

Evi1 is necessary for the differentiation-linked activation of Pparγ2 expression.

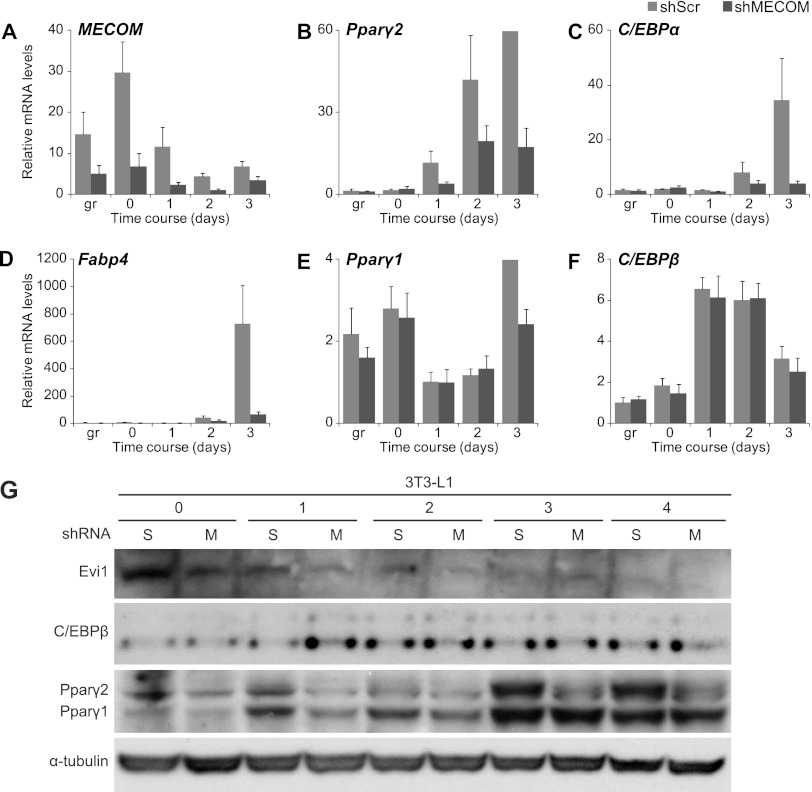

Evi1 was required for the differentiation of preadipocytes into adipocytes, but it was unclear where it was acting in the differentiation pathway. To identify the developmental stage regulated by Evi1, we monitored gene expression during a differentiation time course in MECOM-depleted and control 3T3-L1 cells (Fig. 4). To do this, 3T3-L1 cells were transduced with lentivirus encoding an shRNA for MECOM or a scramble (shScr) sequence control 48 h prior to the addition of hormone cocktail. RNA samples were harvested from subconfluent cultures (growth phase), at confluence (day 0), and at daily time points following addition of adipogenic inducers (days 1 to 3). Gene expression analysis showed that typical adipocyte-specific genes, including Pparγ2, C/EBPα, Fabp4, and AdipoQ were induced to a much greater extent in shScr than in shMECOM cultures at all time points during differentiation (Fig. 4B and D; see also Fig. S4A in the supplemental material). Notably, there was no effect of shMECOM on Pparγ1 mRNA expression until the latest time point (Fig. 4E).

Fig 4.

Time course of 3T3-L1 differentiation following MECOM knockdown. (A to F) Real-time PCR analysis of total RNA from 3T3-L1 cells infected with lentivirus expressing control (shScr) or MECOM (shMECOM) shRNAs. gr, subconfluent growing conditions; day 0, confluent cells at time of induction with differentiation medium; days 1 to 3, time after addition of induction medium. (G) Protein expression during differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells with shRNA knockdown of MECOM. Time points are prior to differentiation (0) or days following induction (1 to 4) in cells infected with control (scramble, S) or MECOM (M) shRNAs.

C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ are known to stimulate Pparγ expression in response to adipogenic inducers (reviewed in reference 8). Notably, C/EBPβ mRNA levels were unaffected by the loss of MECOM in 3T3-L1 cells, being induced to the same extent in shScr and shMECOM cultures 24 h after addition of adipogenic hormones (Fig. 4F). C/EBPδ mRNA was expressed at very low levels and was also reduced by loss of MECOM (see Fig. S4B in the supplemental material). MECOM-knockdown preadipocytes did not appear to spontaneously adopt alternative lineage morphology or markers for either bone (e.g., osteopontin) (see Fig. S4C) or cartilage (e.g., collagen 2a, which was not detected). Importantly, loss of MECOM also led to a substantial reduction in PPARγ protein levels at all time points with no change in C/EBPβ protein levels (Fig. 4G). Interestingly, C/EBPδ protein levels were increased in MECOM-depleted cells at day 2 and thereafter (see Fig. S5), suggesting that MECOM is necessary to transition into the PPARγ-regulated phase of differentiation. Thus, we conclude that MECOM acts in parallel with and/or downstream of C/EBPβ to promote the adipogenic gene program.

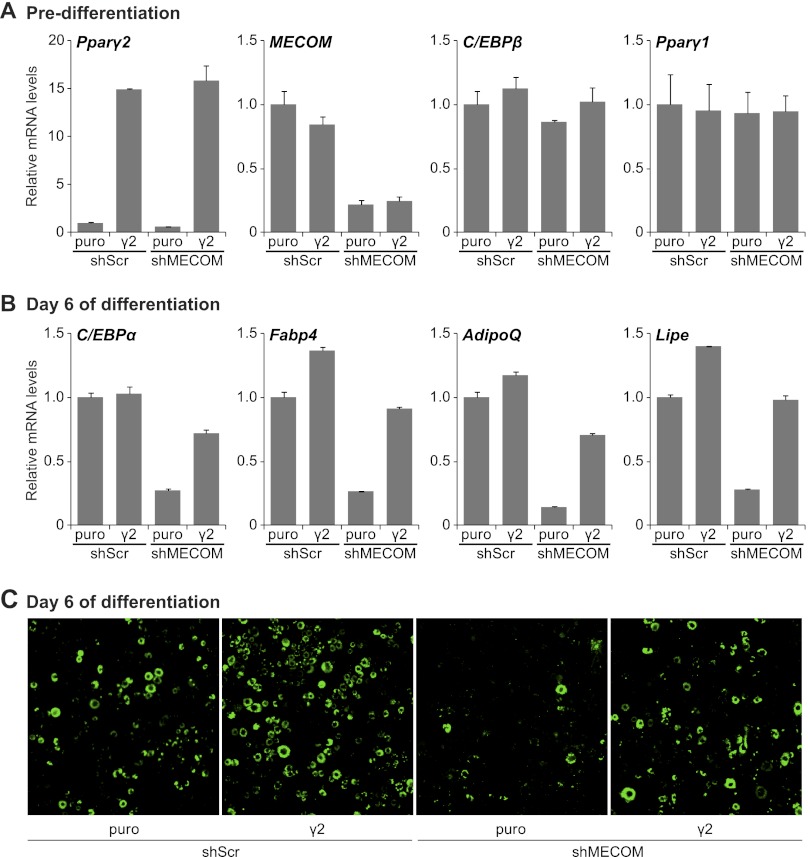

We hypothesized that the induction of Pparγ2 expression at the onset of adipocyte differentiation is an important transcriptional event controlled by MECOM. We therefore tested whether ectopic Pparγ2 expression could bypass the early requirement for Evi1 in adipocyte differentiation. To do this, 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were infected with either PPARγ2- or (control) puromycin (puro)-expressing retrovirus and either shMECOM or shScr vectors. shMECOM expression resulted in a 75 to 80% knockdown of MECOM mRNA in both control and PPARγ2-expressing 3T3-L1 cells before differentiation (Fig. 5A). Pparγ2 was overexpressed approximately 15-fold in predifferentiation cultures; however, the absolute levels were similar to those in fully differentiated adipocytes (data not shown). Ectopic expression of PPARγ2 did not have a noticeable impact on differentiation or adipocyte-specific gene expression in the preadipose state, and neither knockdown of MECOM nor overexpression of PPARγ2 affected C/EBPβ or Pparγ1 expression (Fig. 5A). However, as expected, ectopic expression of PPARγ2 in control (shScr) cells increased the expression levels of PPARγ target and adipocyte-specific genes like Fabp4, AdipoQ, and the hormone sensitive lipase gene (Lipe) at day 6 of differentiation by 25 to 50% (Fig. 5B). Importantly, ectopic expression of PPARγ2 rescued adipocyte differentiation in MECOM-depleted cells (Fig. 5B and C). Gene expression analysis demonstrated that ectopic expression of PPARγ2 fully restored the mRNA levels of Fabp4 and Lipe in MECOM-deficient adipocytes and resulted in an ∼75% recovery in transcript levels of C/EBPα and AdipoQ. Consistent with the molecular analysis, MECOM-depleted cells underwent morphological differentiation into lipid droplet-containing (Bodipy 493/503-stained) adipocytes only with PPARγ2 expression and at a similar efficiency to shScr control cultures (Fig. 5C). Thus, physiological levels of PPARγ can drive adipogenesis in the absence of MECOM. This result suggests that MECOM is specifically required for the early differentiation-linked induction of PPARγ2.

Fig 5.

Exogenous PPARγ2 rescues the shEvi1-induced deficiency in 3T3-L1 differentiation. Growing 3T3-L1 cells were sequentially infected with shScr- or shEvi1-expressing lentivirus, followed by empty (puro)- or PPARγ2 (γ2)-expressing retrovirus. (A and B) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of gene expression prior to induction (predifferentiation) or after 6 days of differentiation. Values are normalized to Tbp expression and shown relative to the shScr control. (C) Bodipy 493/503 staining of lipid droplets in cells after 6 days of differentiation.

Evi1 interacts with C/EBPβ.

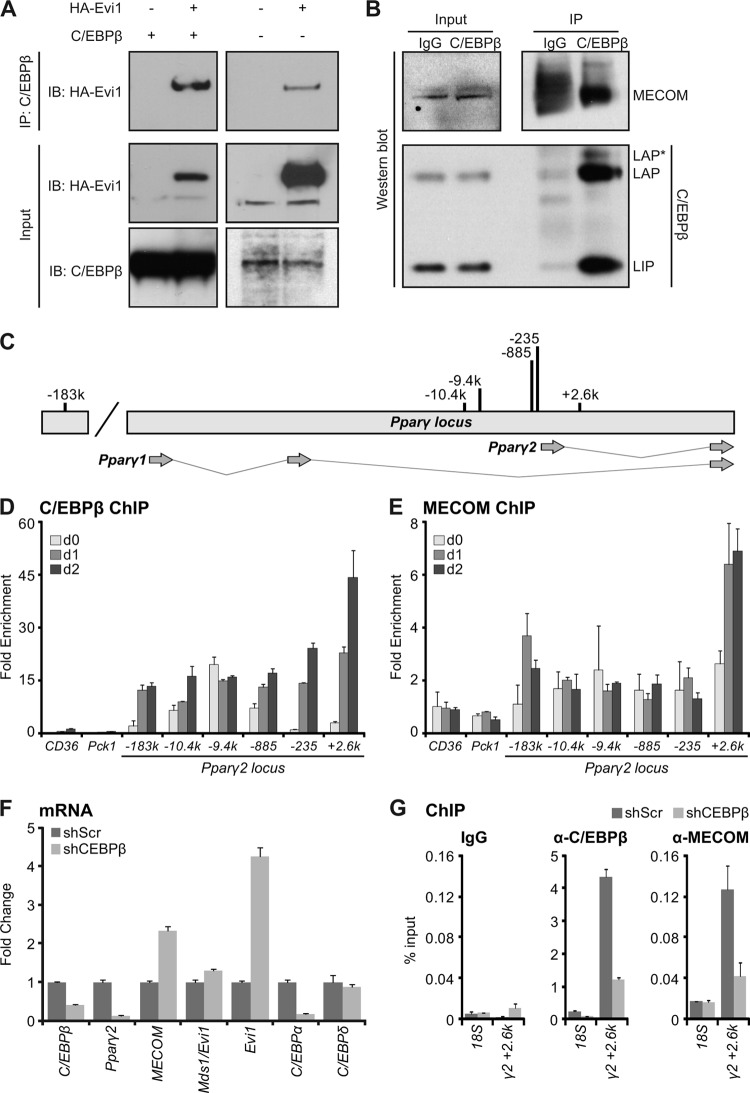

To explain the adipogenic action of Evi1, we investigated whether Evi1 could physically interact with C/EBPβ to initiate Pparγ2 expression. Using immunoprecipitation assays in 293 cells, we readily detected Evi1 in a protein complex with C/EBPβ in cells cotransfected with both factors (Fig. 6A, left panels). Furthermore, immunoprecipitates of endogenously expressed C/EBPβ protein also contained substantial levels of transfected HA-tagged Evi1 protein (Fig. 6A, right panels). Importantly, endogenous C/EBPβ and MECOM (Evi1 and Mds1-Evi1) proteins physically interact in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes 1 day after induction of differentiation (Fig. 6B). Thus, C/EBPβ physically interacts with MECOM during the initial stages of adipogenesis when MECOM is required for activation of Pparγ2 transcription.

Fig 6.

MECOM associates with C/EBPβ and with C/EBPβ DNA binding sites at the Pparγ2 promoter. (A) HA-Evi1 and C/EBPβ were coexpressed in 293 cells for 48 h before protein complex immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-C/EBPβ antibody for Western analysis with anti-MECOM (left), anti-HA (right), or anti-C/EBPβ. (B) Endogenous MECOM and C/EBPβ interact at day 1 of 3T3-L1 differentiation. Anti-C/EBPβ or IgG (control) antibodies were used to immunoprecipitate protein complexes for Western analysis with anti-MECOM or anti-C/EBPβ antibodies. (C) Schematic of C/EBPβ binding sites at the Pparγ2 promoter. k, kb. (D and E) Chromatin immunoprecipitation. 3T3-L1 cells were harvested for ChIP with anti-C/EBPβ or anti-MECOM at confluence (day 0 [d0]) or at one (d1) or two (d2) days of adipocyte differentiation. Chromatin enrichment was analyzed by real-time PCR as percent input recovery and normalized to 18S percent input to produce a fold enrichment over background. Pparγ2 locus primers are denoted (e.g., +2.6k) in kilobase pairs relative to the Pparγ2 transcriptional start site. (F and G) shRNA C/EBPβ knockdown in 3T3-L1 cells. Panel F shows gene expression at day 1 of differentiation normalized to Tbp and relative to shScr controls. Panel G shows ChIP at day 1 using IgG, anti-C/EBPβ, or anti-MECOM. Enrichment is shown as percent input recovery of 18S or Pparγ2 kb +2.6 (γ2 + 2.6k) chromatin.

Evi1 and C/EBPβ associate with chromatin at the Pparγ2 locus.

We next examined whether Evi1 and C/EBPβ bind to regulatory sites in the Pparγ gene during adipogenesis. C/EBPβ has been shown to bind to numerous sites near and within Pparγ (36, 38). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) of endogenous MECOM in 3T3-L1 cells was used to test for the presence of MECOM at loci that are also occupied by C/EBPβ. Six candidate binding sites ranging from kb −183 to +3 relative to the Pparγ2 transcription start site were assayed (Fig. 6C). ChIP analysis showed that all of these sites were bound by C/EBPβ, with dynamic changes in enrichment occurring through the initial days of adipogenesis (Fig. 6D). Interestingly, the kb +2.6 site in intron 1 of Pparγ2 was also reproducibly enriched for binding of MECOM, in contrast to adjacent loci (Fig. 6E) or an IgG control ChIP (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). Notably, the binding of MECOM to this site was specifically increased 1 day after adipocyte differentiation was induced, which is the time point at which Evi1 protein accumulates. There was also a less robust association of MECOM with the kb −183 site. The other C/EBPβ sites were not bound by MECOM despite occupancy by C/EBPβ, indicating that MECOM and C/EBPβ are not constitutively associated. The MECOM-bound regions in Pparγ did not contain any Evi1 consensus DNA binding motifs (11, 27), suggesting that MECOM likely binds indirectly at these loci. To test whether C/EBPβ is indeed required for recruitment of MECOM to Pparγ, we performed ChIP studies in C/EBPβ-depleted 3T3-L1 cells after 1 day of differentiation. Retroviral expression of a C/EBPβ-specific shRNA reduced C/EBPβ expression and blocked expression of Pparγ2 (Fig. 6F). As expected, C/EBPβ DNA binding was reduced at all of the tested C/EBPβ binding sites in the PPARγ locus (Fig. 6G; see also Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). Notably, loss of C/EBPβ coincided with a dramatic decrease in MECOM binding at the kb +2.6 site but not other C/EBPβ sites (Fig. 6G; see also Fig. S7) despite elevated MECOM (and Evi1, in particular) levels. Altogether, our results suggest that MECOM (Evi1 and/or Mds1-Evi1) interacts with the Pparγ gene via association with C/EBPβ.

We next asked whether Evi1 expression in nonadipogenic NIH 3T3 cells resulted in the recruitment of activating histone modifications (H3K4me2 or H3K9Ac) at specific sites in Pparγ (see Fig. S8A in the supplemental material) (19, 22). Interestingly, control and Evi1-expressing samples showed similar levels of H3K4me2 and H3K9Ac at most loci upstream of the Pparγ2 promoter. However, both marks were markedly enriched at the kb +2.6 site in response to Evi1 expression (see Fig. S8B). These data support the hypothesis that Evi1 binds with C/EBPβ specifically at the kb +2.6 site to facilitate chromatin remodeling and Pparγ2 transcription.

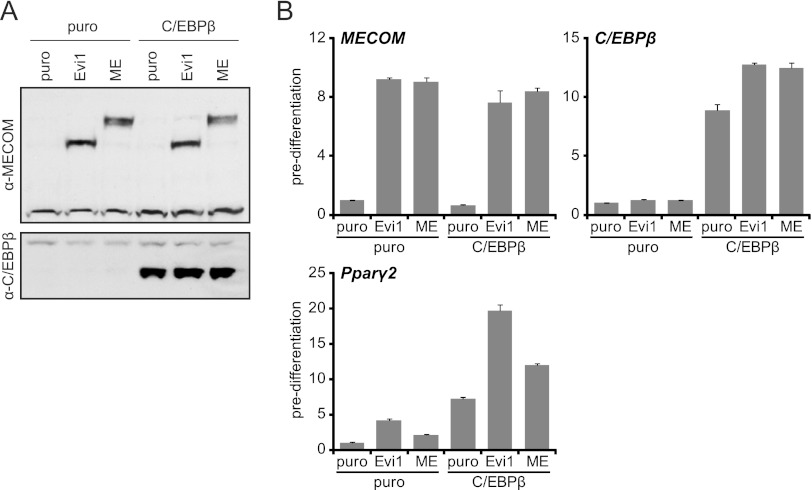

Evi1 and C/EBPβ coactivate adipogenesis.

Our studies suggest that Evi1 and/or Mds1-Evi1 stimulates the transcriptional activity of C/EBPβ to increase Pparγ2 gene expression. However, reporter gene-based transcription assays using various regions of the Pparγ gene driving expression of a luciferase reporter gene did not reveal a reproducible effect for Evi1 or Mds-Evi in promoting C/EBPβ function at the sites identified by ChIP. Therefore, to assess a functional interaction between Evi1/Mds1-Evi1 and C/EBPβ, we analyzed the expression of endogenous Pparγ1, Pparγ2, and other target genes in NIH 3T3 cells in response to ectopic expression of each factor alone or in combination. Western blot analysis showed that we expressed similar levels of Evi1 and Mds-Evi1 with or without C/EBPβ in NIH 3T3 cells prior to induction of adipocyte differentiation (Fig. 7A). In the fibroblast state, cells expressing Evi1 or C/EBPβ alone precociously activated Pparγ2 expression by ∼4- to 6-fold, whereas Mds-Evi1 had a marginal effect (Fig. 7B). Strikingly however, coexpression of Evi1 and C/EBPβ dramatically increased the levels of Pparγ2 in fibroblasts prior to the influence of adipogenic agents. Notably, the increase in Pparγ2 levels by the combination of C/EBPβ and Evi1 was much more pronounced than with C/EBPβ and Mds1-Evi1. Evi1 and C/EBPβ acted together to increase Pparγ2 levels with no effect on Pparγ1, for which no transcripts were detected by real-time PCR. Consistent with these results, coexpression of C/EBPβ and Evi1 was much more potent in promoting terminal adipogenesis than either factor alone or the combination of C/EBPβ and Mds1-Evi1 (see Fig. S9 in the supplemental material). Together, these data strongly suggest that Evi1 and C/EBPβ cooperate to drive Pparγ2 expression in the preadipocyte-to-adipocyte transition.

Fig 7.

MECOM cooperates with C/EBPβ to convert NIH 3T3 cells into adipocytes. NIH 3T3 cells were stably infected with empty (puro)-, Evi1-, or Mds1-Evi1 (ME)-expressing retrovirus and subsequently reinfected with empty (puro)- or C/EBPβ-expressing retrovirus. (A) Western blot analysis of total protein prior to differentiation with anti-MECOM or anti-C/EBPβ. (B) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of gene expression prior to differentiation. Values are normalized to Tbp expression, and fold changes are relative to the puro controls.

DISCUSSION

This study reveals that Evi1 is an important transcriptional regulator of adipocyte differentiation. Specifically, Evi1 acts in conjunction with C/EBPβ to increase expression of Pparγ2 and thus initiate the developmental gene program of adipogenesis.

The Pparγ gene is expressed in two isoforms (PPARγ1 and PPARγ2) from separate promoter regions. PPARγ2 is expressed specifically in adipose cells, whereas PPARγ1 is broadly expressed in many cell types (7, 21). PPARγ2 contains an extra 30 amino acids at the N terminus that boosts its ligand-independent transactivation function relative to PPARγ1 (28, 44). Surprisingly, however, the molecular events controlling the distinct expression patterns of Pparγ1 versus Pparγ2 have remained elusive. Our results in both gain- and loss-of-function analyses reveal that Evi1 selectively controls Pparγ2 expression in adipocytes. This Evi1-dependent transcription of Pparγ2 is mediated, at least in part, via a physical interaction between Evi1 and C/EBPβ.

MECOM was required for the induction of Pparγ2 expression and adipogenesis in preadipocytes (Fig. 3 and 4). Interestingly, we found that loss of MECOM blocked the mitotic clonal expansion (MCE) of 3T3-L1 cells (see Fig. S3C in the supplemental material) that normally occurs at the onset of differentiation (40). The lack of MCE likely contributed to the reduced differentiation of MECOM-depleted cells. However, ectopic expression of Evi1 in NIH 3T3 cells caused the precocious expression of Pparγ2 prior to differentiation (Fig. 7B; see also Fig. S8A). Moreover, MECOM and C/EBPβ bound to regulatory elements near the Pparγ2 promoter at day 1 and day 2 of 3T3-L1 differentiation (Fig. 6D and E) when Pparγ2 expression increased (Fig. 4B). Together, our results strongly suggest that Evi1 directly regulates Pparγ2 transcription during adipocyte differentiation. Whether MCE facilitates the recruitment of Evi1 to the Pparγ gene will require further study.

C/EBPβ is widely expressed in many cell types and has been shown to bind to many sites at or near the Pparγ locus (36, 38), but the functional significance of many of these sites has not been studied. Interestingly, Evi1 was detected by chromatin immunoprecipitation at only two of the six C/EBPβ binding regions (kb +2.6 and −183) (Fig. 6D and E), with the association of Evi1 with the kb +2.6 site being particularly robust, and this was lost in the absence of C/EBPβ (Fig. 6G). Thus, the presence of Evi1 with C/EBPβ may define the functional enhancers for Pparγ2 transcription. Evi1 was not able to increase C/EBPβ function in transient, plasmid-based transcription assays when Evi1-C/EBPβ binding regions (kb +2.6 and −183) were cloned upstream of a luciferase reporter gene. One possible explanation for this is that Evi1 recruits histone-modifying enzymes to cause structural changes in the chromatin around Pparγ2 rather than directly stimulating transcription. A detailed analysis of long-range DNA interactions at this locus will be needed to test this idea.

Evi1 and its longer form, Mds1-Evi1, have been shown in other cell lineages to activate or repress transcription through several proposed mechanisms, including via direct DNA binding (47) or through coregulatory effects (as shown here). In particular, Evi1 interacts with numerous coregulators, including the corepressor CtBP2 (26, 43), acetyltransferases CBP and p300/CBP-associated factor (P/CAF) (4), chromatin remodelers Brg1 and BRM (5), histone methyltransferases SUV39H1 (3) and Polycomb complex (49), and DNA methyltransferase (35). Together, these interactions suggest that Evi1 may have a fundamental role in coordinating the restructuring of chromatin in multiple genetic programs. Another interesting question is what determines the recruitment of Evi1 to these specific C/EBPβ DNA-binding sites and not others. The structural and mechanistic details that mediate the coactivator function of Evi1 will be an important area for future study.

Evi1 exists in at least two distinct forms, Mds1-Evi1 and Evi1, expressed from the MECOM locus through different promoters. The Mds-Evi1 isoform, but not Evi1, includes an amino-terminal PR domain that characterizes proteins in the PrdI-BF1-Riz1 histone methyltransferase family (9). This arrangement suggests that Mds-Evi1 and Evi1 could have distinct functions at a common set of target loci recognized through their two identical zinc finger domains. Interestingly, the shorter Evi1 isoform was substantially more potent than Mds-Evi1 in inducing adipogenesis (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, the expression of the two isoforms during differentiation (Fig. 1A and B) strongly suggests a prominent role for Evi1 at the earliest time points, whereas the expression of Mds1-Evi1 remains detectable throughout adipogenesis. We speculate that the absence of a PR domain in Evi1 allows for distinct coactivating functions that are required during early adipogenic induction. The PR domain-containing Mds1-Evi1 may compete with residual Evi1 at later stages or substitute for Evi1 to maintain expression of adipogenic genes. It will now be important to examine the role of Evi1 and Mds1-Evi1 in mature adipocyte function using gain- and loss-of-function studies in cells and animals.

Evi1 is most closely related to Prdm16 within the 17-member PR domain protein family. Prdm16 is expressed at high levels in brown adipocytes relative to white adipocytes, where it drives a brown fat-specific gene program (34). The structural and sequence homology between Evi1 and Prdm16 suggests that these factors may have some common or similar actions in adipose cells. Brown and white adipocytes arise from separate developmental origins; therefore, Prdm16 and Evi1 may regulate similar processes in brown and white fat lineages, respectively. For instance, Evi1, like Prdm16, stimulates adipogenesis through a physical association with C/EBPβ (17), albeit in different cell types. However, Prdm16 protein has not been localized to specific regulatory regions in Pparγ, and it will be interesting to examine whether Prdm16 binds in the Pparγ locus to the same sites in brown fat cells as Evi1 does in white fat cells. Despite inducing common basic features of the fat phenotype, Prdm16 potently induces brown adipose-related genes (34), whereas Evi1 does not. This result suggests that the ability of Prdm16 to activate the brown fat genetic program is mediated via a domain that is not shared with Evi1. Notably, white adipose tissue can acquire molecular and functional features of brown fat in response to prolonged cold exposure or after treatment with β-adrenergic agents, but the emergence of this “beige” fat requires Prdm16 (33). Any role that Evi1 might play in this process remains to be studied. Conceivably, a balance between the levels of Evi1 and Prdm16 may determine the relative phenotypic expression of the white or brown fat programs.

In summary, we have identified Evi1 as a key competency factor that allows preadipocytes to undergo differentiation. Evi1 likely regulates other critical gene programs in adipocytes, functioning as a coregulatory protein with C/EBPβ and other transcription factors or as a direct DNA-binding transcription factor. Elucidating how Evi1 controls adipose expansion and adipocyte function will be essential for our understanding of adipose biology in development and disease.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship award from the American Heart Association to J.I. (10POST3790054) and by grants from the Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center (DK19525) and NIDDK/NIH (R00 DK081605) to P.S.

We thank Morris Birnbaum (University of Pennsylvania) for providing 3T3-L1 cells and Archibald Perkins (University of Rochester) for providing anti-Evi1 antibody.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 2 April 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Barak Y, et al. 1999. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol. Cell 4:585–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boden G, et al. 2005. Thiazolidinediones upregulate fatty acid uptake and oxidation in adipose tissue of diabetic patients. Diabetes 54:880–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cattaneo F, Nucifora G. 2008. EVI1 recruits the histone methyltransferase SUV39H1 for transcription repression. J. Cell. Biochem. 105:344–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chakraborty S, Senyuk V, Sitailo S, Chi Y, Nucifora G. 2001. Interaction of EVI1 with cAMP-responsive element-binding protein-binding protein (CBP) and p300/CBP-associated factor (P/CAF) results in reversible acetylation of EVI1 and in co-localization in nuclear speckles. J. Biol. Chem. 276:44936–44943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chi Y, Senyuk V, Chakraborty S, Nucifora G. 2003. EVI1 promotes cell proliferation by interacting with BRG1 and blocking the repression of BRG1 on E2F1 activity. J. Biol. Chem. 278:49806–49811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cristancho AG, Lazar MA. 2011. Forming functional fat: a growing understanding of adipocyte differentiation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12:722–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Escher P, et al. 2001. Rat PPARs: quantitative analysis in adult rat tissues and regulation in fasting and refeeding. Endocrinology 142:4195–4202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Farmer SR. 2006. Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metab. 4:263–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fears S, et al. 1996. Intergenic splicing of MDS1 and EVI1 occurs in normal tissues as well as in myeloid leukemia and produces a new member of the PR domain family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:1642–1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH. 2007. Cause-specific excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA 298:2028–2037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Funabiki T, Kreider BL, Ihle JN. 1994. The carboxyl domain of zinc fingers of the Evi-1 myeloid transforming gene binds a consensus sequence of GAAGATGAG. Oncogene 9:1575–1581 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Graham FL, van der Eb AJ. 1973. Transformation of rat cells by DNA of human adenovirus 5. Virology 54:536–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Green H, Kehinde O. 1975. An established preadipose cell line and its differentiation in culture. II. Factors affecting the adipose conversion. Cell 5:19–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gupta RK, et al. 2010. Transcriptional control of preadipocyte determination by Zfp423. Nature 464:619–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hossain P, Kawar B, El Nahas M. 2007. Obesity and diabetes in the developing world—a growing challenge. N. Engl. J. Med. 356:213–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Joe AWB, Yi L, Even Y, Vogl AW, Rossi FMV. 2009. Depot-specific differences in adipogenic progenitor abundance and proliferative response to high-fat diet. Stem Cells 27:2563–2570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kajimura S, et al. 2009. Initiation of myoblast to brown fat switch by a PRDM16-C/EBP-beta transcriptional complex. Nature 460:1154–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kubota N, et al. 2006. Pioglitazone ameliorates insulin resistance and diabetes by both adiponectin-dependent and -independent pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 281:8748–8755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lefterova MI, et al. 2008. PPARγ and C/EBP factors orchestrate adipocyte biology via adjacent binding on a genome-wide scale. Genes Dev. 22:2941–2952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lehmann JM, et al. 1995. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma). J. Biol. Chem. 270:12953–12956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Medina-Gomez G, et al. 2007. PPAR gamma 2 prevents lipotoxicity by controlling adipose tissue expandability and peripheral lipid metabolism. PLoS Genet. 3:e64 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mikkelsen TS, et al. 2010. Comparative epigenomic analysis of murine and human adipogenesis. Cell 143:156–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miyazaki Y, et al. 2004. Effect of pioglitazone on circulating adipocytokine levels and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89:4312–4319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nielsen R, et al. 2008. Genome-wide profiling of PPARγ:RXR and RNA polymerase II occupancy reveals temporal activation of distinct metabolic pathways and changes in RXR dimer composition during adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 22:2953–2967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Okuno A, et al. 1998. Troglitazone increases the number of small adipocytes without the change of white adipose tissue mass in obese Zucker rats. J. Clin. Invest. 101:1354–1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Palmer S, et al. 2001. Evi-1 transforming and repressor activities are mediated by CtBP co-repressor proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 276:25834–25840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Perkins AS, Kim JH. 1996. Zinc fingers 1–7 of EVI1 fail to bind to the GATA motif by itself but require the core site GACAAGATA for binding. J. Biol. Chem. 271:1104–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ren D, Collingwood TN, Rebar EJ, Wolffe AP, Camp HS. 2002. PPARγ knockdown by engineered transcription factors: exogenous PPARγ2 but not PPARγ1 reactivates adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 16:27–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rodbell M. 1964. Metabolism of isolated fat cells. I. Effects of hormones on glucose metabolism and lipolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 239:375–380 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rodeheffer MS, Birsoy K, Friedman JM. 2008. Identification of white adipocyte progenitor cells in vivo. Cell 135:240–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rosen ED, et al. 1999. PPARγ is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Cell 4:611–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Salma N, Xiao H, Imbalzano AN. 2006. Temporal recruitment of CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins to early and late adipogenic promoters in vivo. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 36:139–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Seale P, et al. 2011. Prdm16 determines the thermogenic program of subcutaneous white adipose tissue in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121:96–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Seale P, et al. 2007. Transcriptional control of brown fat determination by PRDM16. Cell Metab. 6:38–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Senyuk V, Premanand K, Xu P, Qian Z, Nucifora G. 2011. The oncoprotein EVI1 and the DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3 co-operate in binding and de novo methylation of target DNA. PLoS One 6:e20793 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Siersbæk R, et al. 2011. Extensive chromatin remodelling and establishment of transcription factor “hotspots” during early adipogenesis. EMBO J. 30:1459–1472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smyth MJ, Sparks RL, Wharton W. 1993. Proadipocyte cell lines: models of cellular proliferation and differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 106:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Steger DJ, et al. 2010. Propagation of adipogenic signals through an epigenomic transition state. Genes Dev. 24:1035–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stewart SA, et al. 2003. Lentivirus-delivered stable gene silencing by RNAi in primary cells. RNA 9:493–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tang Q-Q, Otto TC, Lane MD. 2003. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta is required for mitotic clonal expansion during adipogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:850–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tang W, et al. 2008. White fat progenitor cells reside in the adipose vasculature. Science 322:583–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. 1994. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPAR gamma 2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell 79:1147–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Turner J, Crossley M. 1998. Cloning and characterization of mCtBP2, a co-repressor that associates with basic Krüppel-like factor and other mammalian transcriptional regulators. EMBO J. 17:5129–5140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Werman A, et al. 1997. Ligand-independent activation domain in the N terminus of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ). Differential activity of PPARγ1 and -2 isoforms and influence of insulin. J. Biol. Chem. 272:20230–20235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wu Z, Bucher NL, Farmer SR. 1996. Induction of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma during the conversion of 3T3 fibroblasts into adipocytes is mediated by C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, and glucocorticoids. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:4128–4136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wu Z, Xie Y, Bucher NL, Farmer SR. 1995. Conditional ectopic expression of C/EBPβ in NIH-3T3 cells induces PPARγ and stimulates adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 9:2350–2363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yatsula B, et al. 2005. Identification of binding sites of EVI1 in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280:30712–30722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ye J-M, et al. 2004. Direct demonstration of lipid sequestration as a mechanism by which rosiglitazone prevents fatty-acid-induced insulin resistance in the rat: comparison with metformin. Diabetologia 47:1306–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yoshimi A, et al. 2011. Evi1 represses PTEN expression and activates PI3K/AKT/mTOR via interactions with polycomb proteins. Blood 117:3617–3628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.