Abstract

Meconium ileus, intestinal obstruction in the newborn, is caused in most cases by CFTR mutations modulated by yet-unidentified modifier genes. We now show that in two unrelated consanguineous Bedouin kindreds, an autosomal-recessive phenotype of meconium ileus that is not associated with cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by different homozygous mutations in GUCY2C, leading to a dramatic reduction or fully abrogating the enzymatic activity of the encoded guanlyl cyclase 2C. GUCY2C is a transmembrane receptor whose extracellular domain is activated by either the endogenous ligands, guanylin and related peptide uroguanylin, or by an external ligand, Escherichia coli (E. coli) heat-stable enterotoxin STa. GUCY2C is expressed in the human intestine, and the encoded protein activates the CFTR protein through local generation of cGMP. Thus, GUCY2C is a likely candidate modifier of the meconium ileus phenotype in CF. Because GUCY2C heterozygous and homozygous mutant mice are resistant to E. coli STa enterotoxin-induced diarrhea, it is plausible that GUCY2C mutations in the desert-dwelling Bedouin kindred are of selective advantage.

Main Text

Meconium ileus (MI), intestinal obstruction by inspissated meconium in the distal ileum and cecum, develops in utero and presents shortly after birth as failure to pass meconium.1 Some 80% of MI cases are caused by cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR [MIM 602421]) mutations.2,3 In fact, 15%–20% of infants with cystic fibrosis (CF [MIM 219700]) develop MI as a presenting symptom.1 The predisposition to MI in CF is genetically determined;4–8 some CFTR mutations lead to MI at a higher incidence than others.6,9–17 This predisposition is modified by yet other, unidentified genes, residing in several genomic loci.16–22 Non-CF MI can be caused by an array of etiologies, from defects in intestinal innervation to pancreatic insufficiency and meconium plug syndrome, to various anorectal malformations.23

We have previously described inbred consanguineous Bedouin kindred with autosomal-recessive MI, a normal sweat test, and no further clinical stigmata of CF.24 Intestinal biopsy done in three of the affected individuals demonstrated normal ganglions and cholinergic neurons. On the basis of the extended pedigree (Figure 1A, family 1), we assumed a founder effect. Following Soroka Medical Center institutional review board approval and informed consent, DNA samples of 11 affected and 26 nonaffected individuals from the kindred were obtained. Homozygosity of affected individuals at the CFTR locus was ruled out via polymorphic markers D7S2460, D7S677, and D7S655 within CFTR as previously described25,26 (data not shown). Genome-wide linkage analysis (ABI PRISM Linkage Mapping Set, Applied Biosystems) was done as previously described,25,26 and identified a single locus of homozygosity on chromosome 12p13 (spanning 9.5 Mb between markers D12S366 and D12S310) that was common to all affected individuals. Fine mapping of the locus was done with polymorphic markers as previously described26 and narrowed down the locus to 4 Mb between markers D12391 and Ch12_TG (Figure 1B). Maximal two-point LOD score (SUPERLINK)27 was 4.1 (theta = 0) at D12S1580. Of the 40 genes within that locus, our S2G software28,29 identified GUCY2C (MIM 601330) as the primary candidate gene. Sequencing of the entire coding sequence and exon-intron boundaries of GUCY2C (NM_004963.3) identified a single homozygous mutation, c.1160A>G, leading to p.(Asp387Gly) amino acid substitution in the encoded protein. The mutation was not found in any SNP or mutation database and was common to all affected individuals (Figure 2). At the position of the c.1160A>G mutation, BanI restriction analysis gave differential cleavage products for the wild-type and mutant sequences (207 bp in the wild-type versus 134 bp and 73 bp fragments in the mutant; PCR amplification primers: forward 5′-TCCAACTTATCTGTCAGGCAAA-3′; reverse 5′-GTTACCCCTCCTCACCCAGT-3′). This differential BanI restriction analysis was used to test the 37 DNA samples in family 1 as well as controls. Of the 24 nonaffected individuals in the kindred, three offspring of a consanguineous marriage and one obligatory carrier were homozygous for the mutation. However, partial penetrance of the phenotype was evident: one of the three that had been examined by ultrasonography late in pregnancy had unequivocal intrauterine sonographic evidence of meconium ileus, yet did pass stools unassisted after birth. Of 240 unrelated Bedouin controls, three3 were found to be heterozygous for the mutation and none were homozygous. The penetrance of the postnatal MI phenotype in c.1160A>G homozygous individuals was 73% (11 affected/15 mutants).

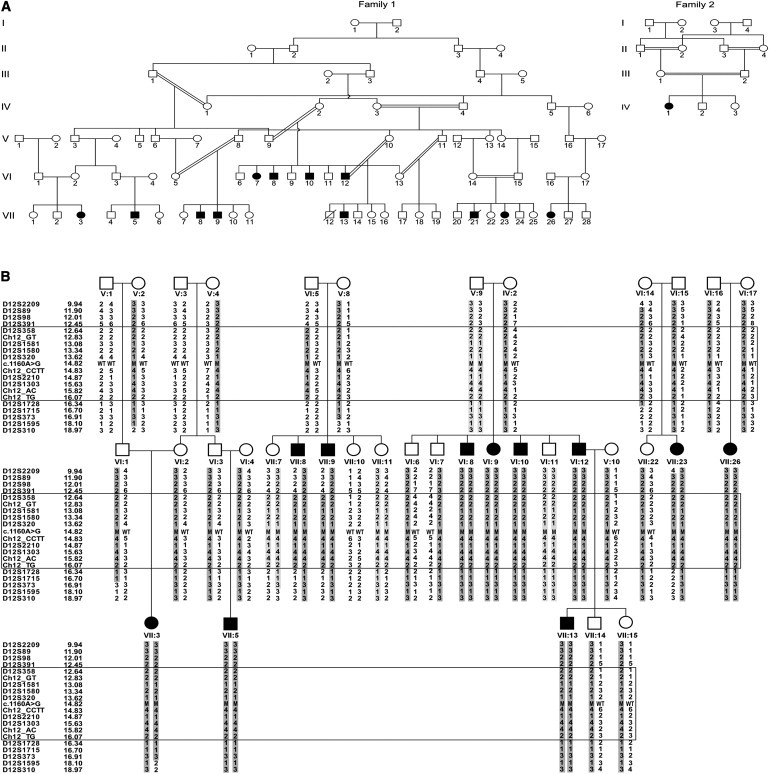

Figure 1.

Family Trees and Linkage Analysis Results

(A) The Israeli-Bedouin Kindred affected with non-CF MI; family 1 and family 2 are not related.

(B) Linkage analysis results (chromosome 12p13, partial pedigree of family 1): the haplotype showing the homozygosity region is boxed. Physical locations of the markers are shown. Individuals VII:8, VII:9 defined the upper boundary of the locus and individual VII:23 defined the lower boundary. For tested individuals, the c.1160A>G mutation status of each allele is marked as wild-type (WT) or mutant (M).

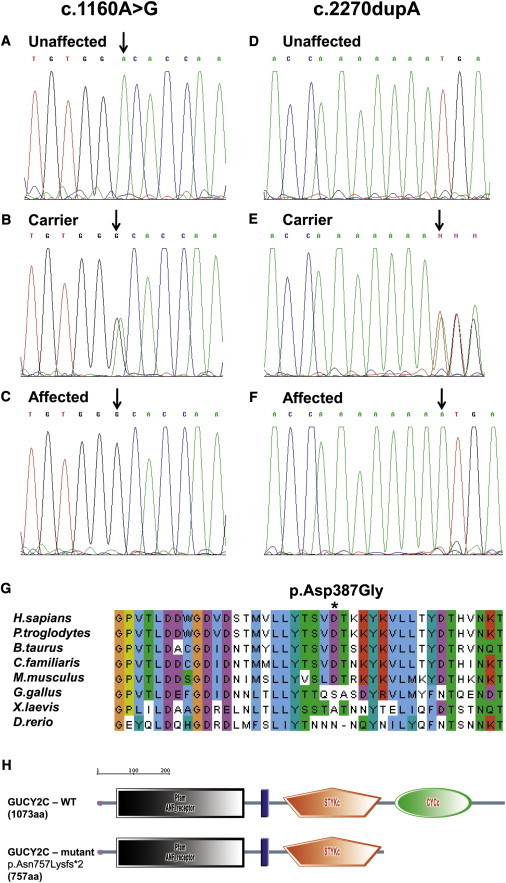

Figure 2.

The c.1160A>G and c.2270dupA GUCY2C Mutations: Homozygosity for the Wild-Type Allele

(A–F) Heterozygosity for the wild-type (A and D) and the mutated alleles (B and E) and homozygosity for the mutated allele (C and F) in normal obligatory carriers and affected individuals of families 1 (A, B, and C) and 2 (D, E, and F). (G) The p.Asp387Gly amino acid substitution: multiple alignment and conservation analysis (ClustalW) of human GUCY2C with its orthologs. (the asterisk [∗] represents the mutated amino acid).

(H) The p.Asn757Lysfs∗2 mutation: deleting the functional domain of the enzyme (SMART).

GUCY2C encodes guanylyl cyclase 2C, a regulator of ion and fluid balance in the intestine and harbors an N-terminal extracellular ligand-binding domain, a single transmembrane domain, and a C-terminal intracytoplasmatic guanylyl cyclase domain.30,31 The extracellular domain of GUCY2C is targeted by either the endogenous ligands, guanylin and related peptide uroguanylin, or by an external ligand, E. coli heat-stable enterotoxin STa.30,32–35 Binding of the physiological ligands or of STa to the extracellular domain of GUCY2C activates the intracellular cyclase domain, which catalyzes the synthesis of the second messenger cyclic GMP (cGMP) from GTP.31–35 Elevated levels of cGMP in response to ligand binding cross-activate cGMP-dependent protein kinase G II (PKGII); this activation leads to phosphorylation and subsequent opening of the CFTR.31 This signaling cascade leads to chloride and bicarbonate secretion, ultimately driving the paracellular movement of sodium into the intestinal lumen and regulating intestinal ion and water transport.31

GUCY2C is predominantly localized at the apical brush border membrane of the intestinal epithelium: specific STa-binding sites are present in apical membranes of intestinal epithelium from the duodenum to the distal colon.36,37 The highest density of GUCY2C receptor molecules is found in the proximal small intestine and decreases progressively distally.36 The endogenous peptides guanylin and uroguanylin have a lower affinity for GUCY2C than do the STa peptides and are produced within the intestinal mucosa to serve as paracrine and autocrine regulators of intestinal fluid and electrolyte secretion.38 The toxic E. coli STa peptide is a major pathogen in humans that causes acute and secretory diarrhea in infants, travelers, and domestic animals and has a geographic distribution primarily in developing countries:39,40 when targeted by exogenous STa, GUCY2C is overactivated and intracellular cGMP is induced, resulting in imbalance in the secretion of fluids and chloride from intestinal cells and culminating in severe secretory diarrhea in both humans and mice.31,41–43 Protein levels of GUCY2C receptors are highest in newborns and neonates (in which STa-mediated diarrhea is more frequent and more severe)44, and their affinity and density rapidly decrease with increasing age in humans,45 as well as in mice,46 rats,47 and pigs.48

The p.(Asp387Gly) substitution (Figure 3G) found in the affected individuals is in a conserved aspartate residue of GUCY2C that is within one of the two essential regions of its extracellular ligand-binding domain (Figure 3H) and is immediately adjacent to seven other amino acids that are cardinal to ligand binding.49 In fact, in the porcine GUCY2C ortholog, substitution by alanine residues of Asp387 together with two amino acid residues surrounding it, leads to a significant reduction in ligand-binding and to a reduction in guanylate cyclase activity.30,49

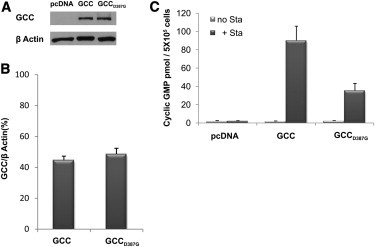

Figure 3.

Functional Analysis of the c.1160A>G Mutation that Produces p.Asp387Gly

(A and B) Immunoblot analysis showing equal amounts of wild-type (GCC) and mutant (GCCD387G) protein in stable transfected HEK293 cell lines used for testing GUCY2C activity.

(C) GUCY2C activity in the presence (+Sta) or absence (no Sta) of E. coli heat-stable enterotoxin STa, tested in HEK293 cells stably transfected with either empty pcDNA vector (negative control) or wild-type (GCC) or mutant (GCCD387G) GUCY2C. Each experiment represents mean ± standard deviation of three repeats. Similar results obtained for three different pairs of cell lines stably overexpressing equal amounts of mutant and wild-type GUCY2C.

To prove experimentally the effect of the p.(Asp387Gly) substitution on the guanylate cyclase activity of the GUCY2C protein, we transfected HEK293 cells (which normally do not express GUCY2C) with either the wild-type or the mutant GUCY2C. To that end, we first cloned the full-length wild-type 3.4 Kb human GUCY2C cDNA into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3 (Invitrogen, Life Technologies), generating a construct we termed pcDNAhGCC. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on the cloned wild-type GUCY2C and generated the mutant gene by overlapping PCR amplification: first, two PCR products, including the mutation site, were amplified with primers designated with the mutation site (one of the primers of each pair). Then, we further used these two PCR products as a template to amplify the whole fragment flanking the mutation region by using the other primers of each pair (primer sequences available upon request). This fragment was subcloned into the pGEM-T easy vector and confirmed by sequencing. The digestion of the resulting construct with EcoRV and BamHI yielded a fragment that contained the mutation region and was inserted in-frame into the corresponding sites in the pcDNAhGCC plasmid. This insertion generated the pcDNAhGCCA1207G clone containing the full length of the mutated GUCY2C (GUCY2CA1207G) cDNA. The final plasmid full sequences were verified by sequencing (data not shown). HEK293 cells were then stably transfected with constructs encoding either the wild-type or the mutant GUCY2C. Transfection was done with TransIT-LT1 reagent (Mirus) per kit instructions, verified by immunoblot analysis as previously described,25 and quantified with a densitometer (Multigage software, Fujifilm). FACS analysis of the HEK293:hGCC and HEK293:hGCCD387G cell lines with the GUCY2C monoclonal antibody and second FITC antibody demonstrated that both the wild-type and the mutated GUCY2C were expressed on the plasma membrane (data not shown). Thus, we concluded that the mutation does not prevent expression of the ligand-stimulated form of the receptor on the cell surface.

We proceeded to test the effect of the p.(Asp387Gly) substitution on guanylate cyclase catalytic activity. We selected three pairs of stable transfected cell lines that express equivalent levels of wild-type versus mutant proteins as demonstrated by immunoblot analysis (Figure 3) and verified quantitatively. Each of the three pairs of cell lines was analyzed (in triplicates) for guanylate cyclase catalytic activity, measuring the formation of intracellular cGMP levels in response to extracellular STa as previously described.34 In essence, HEK293 cells were cultured in 24-well plates. After 24 hr, the culture medium was removed and the cells were incubated in 500 μl serum-free medium containing 100 μM 3-isobutylmethyl-1-xanthine (IBMX) (Sigma) for 10 min at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. Subsequently, 0.1 μM E. coli STa (Sigma) or double-distilled acidified water (pH 2.3) (STa dilution buffer) was added to each well, and incubations were continued for 15 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by aspiration of the incubation media and lysis of the cells by the addition of 500 μl 5% ice-cold trichloracetic acid (TCA) for 30 min at 4°C. The resulting lysates were collected to glass tubes and extracted twice with five volumes of ice-cold water-saturated ether to remove TCA. Residual ether was removed by evaporation in a chemical hood for additional 2 hr. Samples were then frozen at −20°C overnight and lyophilized. After lyopilization, samples were resuspended in acetic acid and acetylated with a mixture of acetic anhydride and triethylamine to increase the sensitivity of the assay. Cyclic GMP production was measured with a commercially available cGMP Enzyme Immunoassay kit (Biomedical Technologies) according to the manufacturer's specifications. All samples were analyzed in triplicate. Significant activation of guanylate cyclase activity was seen in HEK293 cells harboring the wild-type construct (HEK293:GCC) in the presence of STa (Figure 3), comparable to that seen in previously published studies.34 STa-mediated activation of guanylate cyclase in cells transfected with the mutant construct (HEK293:GCCD387G) was ∼60% lower than that in cells harboring the wild-type construct (Figure 3).

The association of GUCY2C with the MI phenotype was further substantiated by our finding of a different deleterious homozygous GUCY2C mutation in a severely affected individual in another, unrelated kindred (Figure 1, family 2): a single case who had severe non-CF MI and was born to Bedouin parents that were first cousins. The MI phenotype in that individual was severe and required surgery. The sweat test was normal, and homozygosity of the affected individual at the CFTR locus was ruled out, whereas homozygosity at the GUCY2C locus was demonstrated (different haplotype than in family 1, data not shown). Sequence analysis of GUCY2C identified a single homozygous mutation, c.2270dupA (Figure 2D–F), not found in 240 Bedouin nonrelated controls or in the two healthy siblings of the affected individual. This c.2270dupA insertion mutation results in a premature stop codon two amino acids following the insertion (p.Asn757Lysfs∗2) and fully abrogates the guanylate cyclase catalytic domain (Figure 2H). It should be noted that both the c.1160A>G mutation and the c.2270dupA insertion mutation were not reported to date in either the HapMap or the 1000 genomes databases.

The fact that downregulation of GUCY2C leads to a CF-like intestinal phenotype is in line with previous data demonstrating that the secretory effect of guanylin is abolished by CFTR blockers.50,51 Moreover, anti-CFTR antibodies have been shown to prevent a cGMP-induced increase in chloride secretion,52 and reduction of CFTR expression in colonic carcinoma cells with antisense oligonucleotides to CFTR mRNA diminished STa-induced chloride secretion. In fact, cells that do not express CFTR do not respond to cGMP until transfected with CFTR cDNA.41 Further support for the interaction between GUCY2C and CFTR comes from studies of mutant mice: mice lacking functional CFTR have virtually no response to an agonist elevating cGMP or cAMP concentrations,38 and heterozygous CFTR+/− mice demonstrate reduction of STa secretory effect by about 50%.53 Because both cGMP and cAMP secretory responses are impaired, CFTR null mice, unlike GUCY2C null mice, suffer from severe obstructions that result in high mortality.54 It should be noted, though, that no complementation studies were done with CFTR and GUCY2C mutant mice to prove their interaction in vivo. Finally, in patients with CF treated with STa and cGMP analogs, the failure to induce chloride and water secretion results in resistance to STa-induced diarrhea.55 Further in-vivo evidence for the connection between GUCY2C and CFTR-associated effects comes from studies of mice lacking functional PKGII, known to mediate the GUCY2C effect on CFTR:56 in PKGII−/− mice, the secretory response of the intestine to STa is markedly reduced.57 As in GUCY2C-deficient mice, mice lacking functional PKGII are otherwise healthy, indicating that other transduction pathways, such as cAMP-protein kinase A, might compensate for a cGMP-signaling deficit in mice.

Although GUCY2C is highly expressed in the intestine, its expression levels in the exocrine pancreas and in the lungs are far lower,36,37 and CFTR activity in those other CF-related tissues is dependent on other activators.1 Thus, affected individuals in this study do not demonstrate any features of the CF phenotype other than MI. Interestingly, SNP rs9300298 at the 12p13.3 locus has been associated with the MI phenotype in CF.22 However, this SNP is located ∼13 Mb from GUCY2C, and further detailed association studies of this locus should be done to test whether GUCY2C is a likely modifier of the MI phenotype in CF.

Finally, we would like to note that mouse experiments suggest a likely evolutionary advantage of GUCY2C heterozygous mutant individuals of the desert-dwelling Bedouin community: in line with the partial penetrance of the human phenotype we describe, null mutant mice lacking functional GUCY2C protein have been generated and are with no evident clinical phenotype when unchallenged.31,42 However, although wild-type mice challenged with the E. coli interotoxin STa die of severe secretory diarrhea, Gucy2c−/− null mutant mice are protected from this detrimental effect. Moreover, even the heterozygous mutant mice demonstrate lower diarrhea-related mortality rates than the wild-type mice.31,42 As the human GUCY2C mutations found are in Bedouin kindred whose habitat is the desert, one can speculate that heterozygosity of GUCY2C mutations might have led to selective advantage at times of infectious diarrhea.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded through a grant from the U.S. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. We thank the Morris Kahn Family Foundation for the kind support. Facilities used were donated in part by the Wolfson Foundation and the Wolfson Family Charitable Trust. G.R.C. was supported through National Institutes of Health grants NHLBI HL068927 and NIDDK DK 044003.

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

1000 Genomes, http://www.1000genomes.org/

ClustalW2–Multiple Sequence Alignment, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/

HapMap, http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://omim.org/

Primer3, http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3

SMART - Simple modular architecture research tool, http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/

SUPERLINK, http://bioinfo.cs.technion.ac.il/superlink/

Tandem Repeats Finder, http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.html

UCSC Genome Browser, http://www.genome.ucsc.edu/

References

- 1.Eggermont E. Gastrointestinal manifestations in cystic fibrosis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1996;8:731–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenstein B.J., Langbaum T.S. Incidence of meconium abnormalities in newborn infants with cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1980;134:72–73. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1980.02130130054016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fakhoury K., Durie P.R., Levison H., Canny G.J. Meconium ileus in the absence of cystic fibrosis. Arch. Dis. Child. 1992;67(10 Spec No):1204–1206. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.10_spec_no.1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boué A., Muller F., Nezelof C., Oury J.F., Duchatel F., Dumez Y., Aubry M.C., Boué J. Prenatal diagnosis in 200 pregnancies with a 1-in-4 risk of cystic fibrosis. Hum. Genet. 1986;74:288–297. doi: 10.1007/BF00282551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allan J.L., Robbie M., Phelan P.D., Danks D.M. Familial occurrence of meconium ileus. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1981;135:291–292. doi: 10.1007/BF00442105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerem E., Corey M., Kerem B., Durie P., Tsui L.C., Levison H. Clinical and genetic comparisons of patients with cystic fibrosis, with or without meconium ileus. J. Pediatr. 1989;114:767–773. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorter R.R., Karimi A., Sleeboom C., Kneepkens C.M.F., Heij H.A. Clinical and genetic characteristics of meconium ileus in newborns with and without cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2010;50:569–572. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181bb3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deering R., Algire M., McWilliams R., Lai T., Naughton K. Meconium Ileus and Liver Disease: An analysis of the CF twin and sibling study. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2004;38:189–369. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mornet E., Simon-Bouy B., Serre J.L., Estivill X., Farrall M., Williamson R., Boue J., Boue A. Genetic differences between cystic fibrosis with and without meconium ileus. Lancet. 1988;1:376–378. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerem E., Corey M., Kerem B.S., Rommens J., Markiewicz D., Levison H., Tsui L.C., Durie P. The relation between genotype and phenotype in cystic fibrosis—analysis of the most common mutation (delta F508) N. Engl. J. Med. 1990;323:1517–1522. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011293232203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamosh A., King T.M., Rosenstein B.J., Corey M., Levison H., Durie P., Tsui L.C., McIntosh I., Keston M., Brock D.J. Cystic fibrosis patients bearing both the common missense mutation Gly----Asp at codon 551 and the delta F508 mutation are clinically indistinguishable from delta F508 homozygotes, except for decreased risk of meconium ileus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1992;51:245–250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerem B., Kerem E. The molecular basis for disease variability in cystic fibrosis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 1996;4:65–73. doi: 10.1159/000472174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feingold J., Guilloud-Bataille M., Clinical Centers of the French CF Registry Genetic comparisons of patients with cystic fibrosis with or without meconium ileus. Ann. Genet. 1999;42:147–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch C., Cuppens H., Rainisio M., Madessani U., Harms H.K., Hodson M.E., Mastella G., Navarro J., Strandvik B., McKenzie S.G., Investigators of the ERCF European Epidemiologic Registry of Cystic Fibrosis (ERCF): Comparison of major disease manifestations between patients with different classes of mutations. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2001;31:1–12. doi: 10.1002/1099-0496(200101)31:1<1::aid-ppul1000>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKone E.F., Emerson S.S., Edwards K.L., Aitken M.L. Effect of genotype on phenotype and mortality in cystic fibrosis: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2003;361:1671–1676. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13368-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mickle J.E., Cutting G.R. Genotype-phenotype relationships in cystic fibrosis. Med. Clin. North Am. 2000;84:597–607. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70243-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blackman S.M., Deering-Brose R., McWilliams R., Naughton K., Coleman B., Lai T., Algire M., Beck S., Hoover-Fong J., Hamosh A. Relative contribution of genetic and nongenetic modifiers to intestinal obstruction in cystic fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1030–1039. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohlfs E.M., Shaheen N.J., Silverman L.M. Is the hemochromatosis gene a modifier locus for cystic fibrosis? Genet. Test. 1998;2:85–88. doi: 10.1089/gte.1998.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zielenski J., Corey M., Rozmahel R., Markiewicz D., Aznarez I., Casals T., Larriba S., Mercier B., Cutting G.R., Krebsova A. Detection of a cystic fibrosis modifier locus for meconium ileus on human chromosome 19q13. Nat. Genet. 1999;22:128–129. doi: 10.1038/9635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zielenski J., Dorfman R., Markiewicz D., Corey M., Ng P., Mak W., Durie P., Tsui L.C. Tagging SNP analysis of the CFM1 locus in CF patients with and without meconium ileus. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2005;S28:206–226. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritzka M., Stanke F., Jansen S., Gruber A.D., Pusch L., Woelfl S., Veeze H.J., Halley D.J., Tümmler B. The CLCA gene locus as a modulator of the gastrointestinal basic defect in cystic fibrosis. Hum. Genet. 2004;115:483–491. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1190-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dorfman R., Li W., Sun L., Lin F., Wang Y., Sandford A., Paré P.D., McKay K., Kayserova H., Piskackova T. Modifier gene study of meconium ileus in cystic fibrosis: Statistical considerations and gene mapping results. Hum. Genet. 2009;126:763–778. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0724-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loening-Baucke V., Kimura K. Failure to pass meconium: Diagnosing neonatal intestinal obstruction. Am. Fam. Physician. 1999;60:2043–2050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tal A., Carmi R., Chai-Am E., Zirkin H., Bar-Ziv J., Freud E. Familial meconium ileus with normal sweat electrolytes. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila.) 1985;24:460–462. doi: 10.1177/000992288502400809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birnbaum R.Y., Zvulunov A., Hallel-Halevy D., Cagnano E., Finer G., Ofir R., Geiger D., Silberstein E., Feferman Y., Birk O.S. Seborrhea-like dermatitis with psoriasiform elements caused by a mutation in ZNF750, encoding a putative C2H2 zinc finger protein. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:749–751. doi: 10.1038/ng1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narkis G., Ofir R., Manor E., Landau D., Elbedour K., Birk O.S. Lethal Congenital Contractural Syndrome Type 2 (LCCS2) is Caused by a Mutation in ERBB3 (Her3), a Modulator of the PI3K/Akt Pathway. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:589–595. doi: 10.1086/520770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fishelson M., Geiger D. Optimizing exact genetic linkage computations. J. Comput. Biol. 2004;11:263–275. doi: 10.1089/1066527041410409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gefen A., Cohen R., Birk O.S. Syndrome to gene (S2G): In-silico identification of candidate genes for human diseases. Hum. Mutat. 2010;31:229–236. doi: 10.1002/humu.21171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen R., Gefen A., Elhadad M., Birk O.S. CSI-OMIM—Clinical Synopsis Search in OMIM. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:65–67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaandrager A.B. Structure and function of the heat-stable enterotoxin receptor/guanylyl cyclase C. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2002;230:73–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mann E.A., Jump M.L., Wu J., Yee E., Giannella R.A. Mice lacking the guanylyl cyclase C receptor are resistant to STa-induced intestinal secretion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;239:463–466. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Currie M.G., Fok K.F., Kato J., Moore R.J., Hamra F.K., Duffin K.L., Smith C.E. Guanylin: An endogenous activator of intestinal guanylate cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:947–951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.3.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamra F.K., Forte L.R., Eber S.L., Pidhorodeckyj N.V., Krause W.J., Freeman R.H., Chin D.T., Tompkins J.A., Fok K.F., Smith C.E. Uroguanylin: Structure and activity of a second endogenous peptide that stimulates intestinal guanylate cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:10464–10468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulz S., Green C.K., Yuen P.S., Garbers D.L. Guanylyl cyclase is a heat-stable enterotoxin receptor. Cell. 1990;63:941–948. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucas K.A., Pitari G.M., Kazerounian S., Ruiz-Stewart I., Park J., Schulz S., Chepenik K.P., Waldman S.A. Guanylyl cyclases and signaling by cyclic GMP. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000;52:375–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krause W.J., Cullingford G.L., Freeman R.H., Eber S.L., Richardson K.C., Fok K.F., Currie M.G., Forte L.R. Distribution of heat-stable enterotoxin/guanylin receptors in the intestinal tract of man and other mammals. J. Anat. 1994;184:407–417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nandi A., Bhandari R., Visweswariah S.S. Epitope conservation and immunohistochemical localization of the guanylin/stable toxin peptide receptor, guanylyl cyclase C. J. Cell. Biochem. 1997;66:500–511. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19970915)66:4<500::aid-jcb9>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joo N.S., London R.M., Kim H.D., Forte L.R., Clarke L.L. Regulation of intestinal Cl- and HCO3-secretion by uroguanylin. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:G633–G644. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.4.G633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giannella R.A. Pathogenesis of acute bacterial diarrheal disorders. Annu. Rev. Med. 1981;32:341–357. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.32.020181.002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giannella R.A. Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxins, guanylins, and their receptors: What are they and what do they do? J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1995;125:173–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chao A.C., de Sauvage F.J., Dong Y.J., Wagner J.A., Goeddel D.V., Gardner P. Activation of intestinal CFTR Cl- channel by heat-stable enterotoxin and guanylin via cAMP-dependent protein kinase. EMBO J. 1994;13:1065–1072. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schulz S., Lopez M.J., Kuhn M., Garbers D.L. Disruption of the guanylyl cyclase-C gene leads to a paradoxical phenotype of viable but heat-stable enterotoxin-resistant mice. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:1590–1595. doi: 10.1172/JCI119683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forte L.R., Currie M.G. Guanylin: A peptide regulator of epithelial transport. FASEB J. 1995;9:643–650. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.8.7768356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Black R.E., Merson M.H., Huq I., Alim A.R., Yunus M. Incidence and severity of rotavirus and Escherichia coli diarrhoea in rural Bangladesh. Implications for vaccine development. Lancet. 1981;1:141–143. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90719-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Majali A.M., Ababneh M.M., Shorman M., Saeed A.M. Interaction of Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin (STa) with its putative receptor on the intestinal tract of newborn kids. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2007;49:35–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al-Majali A.M., Robinson J.P., Asem E.K., Lamar C., Freeman M.J., Saeed A.M. Characterization of the interaction of Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxixn (STa) with its intestinal putative receptor in various age groups of mice, using flow cytometry and binding assays. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1999;49:254–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laney D.W., Jr., Mann E.A., Dellon S.C., Perkins D.R., Giannella R.A., Cohen M.B. Novel sites for expression of an Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin receptor in the developing rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:G816–G821. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.5.G816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jaso-Friedmann L., Dreyfus L.A., Whipp S.C., Robertson D.C. Effect of age on activation of porcine intestinal guanylate cyclase and binding of Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin (STa) to porcine intestinal cells and brush border membranes. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1992;53:2251–2258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hasegawa M., Shimonishi Y. Recognition and signal transduction mechanism of Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin and its receptor, guanylate cyclase C. J. Pept. Res. 2005;65:261–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2005.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cuthbert A.W., Hickman M.E., MacVinish L.J., Evans M.J., Colledge W.H., Ratcliff R., Seale P.W., Humphrey P.P. Chloride secretion in response to guanylin in colonic epithelial from normal and transgenic cystic fibrosis mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;112:31–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guba M., Kuhn M., Forssmann W.G., Classen M., Gregor M., Seidler U. Guanylin strongly stimulates rat duodenal HCO3- secretion: Proposed mechanism and comparison with other secretagogues. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1558–1568. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tien X.Y., Brasitus T.A., Kaetzel M.A., Dedman J.R., Nelson D.J. Activation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by cGMP in the human colonic cancer cell line, Caco-2. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gabriel S.E., Brigman K.N., Koller B.H., Boucher R.C., Stutts M.J. Cystic fibrosis heterozygote resistance to cholera toxin in the cystic fibrosis mouse model. Science. 1994;266:107–109. doi: 10.1126/science.7524148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grubb B.R., Gabriel S.E. Intestinal physiology and pathology in gene-targeted mouse models of cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:G258–G266. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.2.G258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goldstein J.L., Sahi J., Bhuva M., Layden T.J., Rao M.C. Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin-mediated colonic Cl- secretion is absent in cystic fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:950–956. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vaandrager A.B., Smolenski A., Tilly B.C., Houtsmuller A.B., Ehlert E.M.E., Bot A.G.M., Edixhoven M., Boomaars W.E.M., Lohmann S.M., de Jonge H.R. Membrane targeting of cGMP-dependent protein kinase is required for cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl- channel activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:1466–1471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pfeifer A., Aszódi A., Seidler U., Ruth P., Hofmann F., Fässler R. Intestinal secretory defects and dwarfism in mice lacking cGMP-dependent protein kinase II. Science. 1996;274:2082–2086. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]