Abstract

We describe the epidemiology of a pertussis outbreak in Japan in 2010–2011 and Bordetella holmesii transmission. Six patients were infected; 4 patients were students and a teacher at the same junior high school. Epidemiologic links were found between 5 patients. B. holmesii may have been transmitted from person to person.

Keywords: Bordetella infections, pathogen transmission, outbreak, Bordetella holmesii, Bordetella pertussis, pertussis, bacteria, Japan

Bordetella holmesii, a small gram-negative coccoid bacillus that was first reported in 1995 (1), was originally identified as a member of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention nonoxidizer group 2. The organism is associated with bacteremia, endocarditis, and pneumonia, usually in patients with underlying disorders such as asplenia or sickle cell anemia, and has been isolated from blood and sputum samples (1–5). B. holmesii may also be responsible for causing symptoms similar to those of pertussis (whooping cough) in otherwise healthy patients (6). Large surveillance studies in the United States and Canada have shown that the organism was detected in nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) specimens of patients with pertussis-like symptoms (7,8). Although humans may be infected with B. holmesii, transmission of B. holmesii between humans has not yet been fully elucidated.

Pertussis is a highly contagious disease caused by the bacterium B. pertussis. The organism is known to be transmitted from person to person by airborne droplets (9). During a recent pertussis outbreak, we conducted a laboratory-based active surveillance study and detected 76 suspected cases of pertussis. Among these cases, we identified not only B. pertussis infection but also B. holmesii infection. The purpose of this study was to describe the epidemiology of the pertussis outbreak and to determine the epidemiologic relatedness of B. holmesii transmission.

The Study

During 2010–2011, a pertussis outbreak occurred in a suburban town (town A) in Nobeoka City in Miyazaki Prefecture, Japan. Town A has a population of 4,227 persons and an elementary school and junior high school. The first pertussis case (in a 17-year-old boy) was reported in September 2010. From that time, we conducted a laboratory-based active surveillance study in the area until April 2011, in cooperation with clinics, hospitals, and local health departments. Pertussis-suspected cases were defined as an illness with cough lasting for >2 weeks, and pertussis-confirmed cases were defined as the presence of 1 of the following laboratory findings: a culture-positive result for Bordetella species from NPS specimens, or a positive result for molecular testing for Bordetella species.

For molecular testing, we conducted conventional PCR specific for insertion sequence IS481, which is known to detect B. pertussis and B. holmesii, and B. pertussis–specific loop-mediated isothermal amplification assays (10–12). To further confirm B. holmesii infection, B. holmesii–specific real-time PCR specific for the recA gene was also performed as described (8). For confirmed cases of B. holmesii infection, we collected the general information for patients (clinical symptoms, treatment, contact information, and outcome) by face-to-face interview or questionnaire.

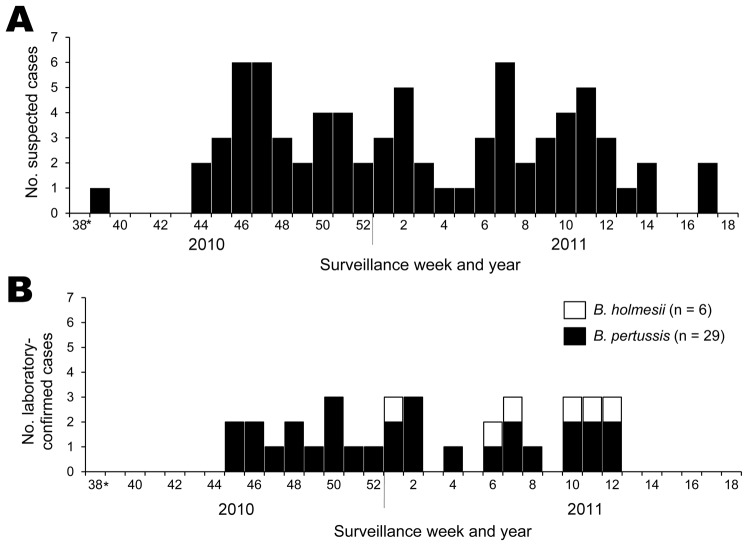

During the pertussis outbreak, we identified 76 suspected pertussis cases. Among these suspected cases, 35 cases were confirmed by laboratory testing and involved persons 2–63 years of age (median age 13 years); 1 case occurred in a 2-year-old child, 14 in 6- to 12-year-old children, 14 in 13–15-year-old children, and 6 in persons >16 years of age. Despite pertussis vaccination rates in childhood of 82.3%−92.6%, most (80%) patients were students 6–12 and 13–15 years of age. Among the 35 confirmed case-patients, 29 and 6 patients showed B. pertussis and B. holmesii infection, respectively. Confirmed cases of B. holmesii infection were observed within the last half of the epidemic curve, i.e., weeks 1–12 of 2011 (Figure 1). There were no cases of co-infection with B. pertussis and B. holmesii.

Figure 1.

Epidemic curve of a pertussis outbreak, September 2010–April 2011, Japan. A) Suspected cases of pertussis. B) Laboratory-confirmed cases of Bordetella pertussis and B. holmesii infection. *As of September 20–26, 2010.

All NPS specimens from patients with B. holmesii infection showed a negative result for the B. pertussis loop-mediated isothermal amplification, but showed positive results in the IS481 PCR and B. holmesii recA real-time PCR (Table 1). B. holmesii-like organisms were obtained from 5 patients, and these were identified as B. holmesii by recA gene sequencing. Patient 6 had been treated with antimicrobial drugs before the culture test, which probably resulted in a culture-negative test result in this patient. Real-time PCR confirmed that patient 6 had a low B. holmesii DNA load (threshold cycle 36.6) in her NPS specimen. All patients experienced paroxysms of coughing without posttussive vomiting, especially at night, and 3 also experienced a whoop (Table 2). Five of 6 patients had a persistent cough lasting >2 weeks. No patients experienced any complications, and they were treated mainly with azithromycin, resulting in complete recovery. None of the patients were immunocompromised.

Table 1. Characteristics of Bordetella holmesii infection in 6 patients during pertussis outbreak, Japan, September 2010–April 2011*.

| Patient no. | Age, y/sex | Duration of cough, d† |

B. holmesii test results |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| recA real-time PCR (Ct)‡ | Culture§ | |||

| 1 | 17/M | 5 | + (28.7) | + |

| 2 | 15/F | 4 | + (23.4) | + |

| 3 | 15/F | >14 | + (21.6) | + |

| 4 | 14/F | 8 | + (25.1) | + |

| 5 | 40/M | 8 | + (27.0) | + |

| 6 | 45/F | 15 | + (36.6) | – |

*All patients had negative results for B. pertussis loop-mediated isothermal amplification and positive results for IS481 PCR. Ct, cycle threshold; –, negative; +, positive. †At time of specimen collection. ‡Detection limit was a Ct value of 38.7, corresponding to 100 fg of DNA of B. holmesii ATCC51541. §All strains were isolated from nasopharyngeal swab specimens.

Table 2. Clinical and epidemiologic characteristics for 6 Bordetella holmesii–infected patients during pertussis outbreak, Japan, September 2010–April 2011*.

| Patient no. | Whoop | Duration of cough | Treatment | DTP vaccine status, no. doses | Medical history | Epidemiologic findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | 10 d | AZM | 4 | Asthma | Student at high school A. His 14-year-old sister, who was given a diagnosis of pertussis, was a student at junior high school B. |

| 2 | + | 28 d | AZM | 4 | −– | Student at junior high school B. Her 18-year-old brother had similar symptoms, but laboratory test results were negative. |

| 3 | – | >4 wk | AZM | 4 | – | Student at junior high school B. Her close friends began coughing after her disease onset. |

| 4 | + | 15 d | AZM | 4 | Chlamydial pneumonia | Student at junior high school B. Her 11-year-old sister was given a diagnosis of pertussis before her disease onset. |

| 5 | −– | 28 d | AZM | UNK | Allergic rhinitis | Teacher at junior high school B in charge of patient 4. |

| 6 | – | 23 d | AZM, CFPN-PI, GRNX | UNK | Rheumatoid arthritis | Medical staff at clinic C, which was visited by patients 1–5. |

*All patients had a paroxysmal cough and coughed at night; none had posttussive vomiting. DTP, diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis; +, positive; AZM, azithromycin; –, negative; UNK, unknown; CFPN-PI, cefcapene pivoxil; GRNX, garenoxacin.

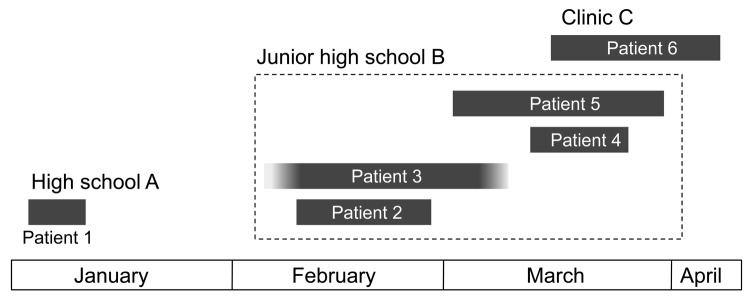

Our surveillance study showed epidemiologic linkage between 5 patients (patients 2–6), but not for patient 1 (Figure 2). Patient 1, a student in high school A, had the first case of B. holmesii infection (probable index case). He lived in a dormitory outside Nobeoka City. However, his family home was in town A in Nobeoka City, and he returned to his home at the end of 2010 and remained there in 2011. Patients 2, 3, and 4 were students at the same junior high school (B) in town A and were close friends. Patient 5 was a teacher at junior high school B and was in charge of patient 4. Patient 6 was a medical practitioner at clinic C, which is 1 of 2 clinics in town A. Patients 1–5 visited clinic C in early January, late February, late February, early March, and late March, 2011, respectively. The duration of illness in patient 1 did not overlap with that of the other patients, whereas that of patients 2–6 clearly overlapped.

Figure 2.

Epidemiologic linkage in 6 patients infected with Bordetella holmesii during pertussis outbreak, Japan, 2011. Duration of illness for each patient is shown as a gray box. Patient 3 provided unreliable information about the date of onset and recovery, but the patient’s cough lasted for >1 month. Epidemiologic linkage was observed between 5 patients (patients 2–6), but not for patient 1.

Conclusions

In the past 16 years, ≈70 B. holmesii clinical strains have been isolated from human patients in several countries, mainly the United States. All reported cases of B. holmesii infection have been sporadic occurrences. Thus, the reservoir of B. holmesii is currently unknown. Moreover, whether B. holmesii is transmitted between humans is not known. In this report, we have demonstrated that 5 patients infected with B. holmesii showed epidemiologic linkage. In particular, the fact that 4 of these patients attended the same junior high school suggests that B. holmesii may be transmitted from person to person.

A previous report suggested that B. holmesii and B. pertussis may co-circulate in young adults (7). However, the relationship between pertussis epidemics and B. holmesii infection is not fully understood. Our active surveillance study showed that B. holmesii infection spread concurrently with the B. pertussis epidemic, but that there was no co-infection of B. holmesii and B. pertussis. Our observations demonstrate that accurate diagnosis is needed to discriminate between B. holmesii and B. pertussis infections during a pertussis outbreak because symptoms associated with these 2 diseases are similar.

In 2012, a patient with B. holmesii infectious pericarditis was reported in Japan (13). This is probably the first case report of B. holmesii infection in Asia. Previous surveillance studies conducted in the United States and Canada have shown low rates (0.1%–0.3%) of B. holmesii infection in patients with cough (7,8). However, in a recent study, B. holmesii DNA was detected in 20% of NPS specimens collected from patients in France who had been given a diagnosis of B. pertussis infection (14). These surveillance data indicate that B. holmesii infection is present in adolescents and adults, and that the organism is associated with pertussis-like symptoms. However, other causes of viral or bacterial respiratory infection cannot be excluded. Because of lack of specific diagnostic tools to detect bordetellae, B. holmesii infection may have been underestimated. Accurate diagnosis and further studies are required to fully elucidate the nature of B. holmesii infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank all medical staff for cooperating during the active surveillance study.

This study was supported by a grant for Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan.

Biography

Dr Kamiya is a pediatrician and medical officer at the National Institute of Infectious Diseases in Tokyo, Japan. His research interests focus on surveillance and control of vaccine-preventable diseases.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Kamiya H, Otsuka N, Ando Y, Odaira F, Yoshino S, Kawano K, et al. Transmission of Bordetella holmesii during pertussis outbreak, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2012 Jul [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1807.120130

References

- 1.Weyant RS, Hollis DG, Weaver RE, Amin MF, Steigerwalt AG, O’Connor SP, et al. Bordetella holmesii sp. nov., a new gram-negative species associated with septicemia. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindquist SW, Weber DJ, Mangum ME, Hollis DG, Jordan J. Bordetella holmesii sepsis in an asplenic adolescent. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:813–5. 10.1097/00006454-199509000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dörbecker C, Licht C, Körber F, Plum G, Haefs C, Hoppe B, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia due to Bordetella holmesii in a patient with frequently relapsing neuphrotic syndrome. J Infect. 2007;54:e203–5. 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panagopoulos MI, Saint Jean M, Brun D, Guiso N, Bekal S, Ovetchkine P, et al. Bordetella holmesii bacteremia in asplenic children: report of four cases initially misidentified as Acinetobacter lwoffii. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3762–4. 10.1128/JCM.00595-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross R, Keidel K, Schmitt K. Resemblance and divergence: the “new” members of the genus Bordetella. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berl). 2010;199:155–63. 10.1007/s00430-010-0148-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang YW, Hopkins MK, Kolbert CP, Hartley PA, Severance PJ, Persing DH. Bordetella holmesii-like organisms associated with septicemia, endocarditis, and respiratory failure. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:389–92. 10.1086/516323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yih WK, Silva EA, Ida J, Harrington N, Lett SM, George H. Bordetella holmesii–like organisms isolated from Massachusetts patients with pertussis-like symptoms. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:441–3. 10.3201/eid0503.990317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guthrie JL, Robertson AV, Tang P, Jamieson F, Drews SJ. Novel duplex real-time PCR assay detects Bordetella holmesii in specimens from patients with pertussis-like symptoms in Ontario, Canada. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1435–7. 10.1128/JCM.02417-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mattoo S, Cherry JD. Molecular pathogenesis, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations of respiratory infections due to Bordetella pertussis and other Bordetella subspecies. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:326–82. 10.1128/CMR.18.2.326-382.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dragsted DM, Dohn B, Madsen J, Jensen JS. Comparison of culture and PCR for detection of Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis under routine laboratory conditions. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:749–54. 10.1099/jmm.0.45585-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamachi K, Toyoizumi-Ajisaka H, Toda K, Soeung SC, Sarath S, Nareth Y, et al. Development and evaluation of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification method for rapid diagnosis of Bordetella pertussis infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1899–902. 10.1128/JCM.44.5.1899-1902.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reischl U, Lehn N, Sanden GN, Loeffelholz MJ. Real-time PCR assay targeting IS481 of Bordetella pertussis and molecular basis for detecting Bordetella holmesii. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1963–6. 10.1128/JCM.39.5.1963-1966.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nei T, Hyodo H, Sonobe K, Dan K, Saito R. Infectious pericarditis due to Bordetella holmesii in an adult patient with malignant lymphoma: first report of a case. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50. Epub ahead of print. 10.1128/JCM.06772-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Njamkepo E, Bonacorsi S, Debruyne M, Gibaud SN, Guillot S, Guiso N. Significant finding of Bordetella holmesii DNA in nasopharyngeal samples from French patients with suspected pertussis. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:4347–8. 10.1128/JCM.01272-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]