Executive Summary

In August 2008, the Medical Advisory Secretariat (MAS) presented a vignette to the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC) on a proposed targeted health care delivery model for chronic care. The proposed model was defined as multidisciplinary, ambulatory, community-based care that bridged the gap between primary and tertiary care, and was intended for individuals with a chronic disease who were at risk of a hospital admission or emergency department visit. The goals of this care model were thought to include: the prevention of emergency department visits, a reduction in hospital admissions and re-admissions, facilitation of earlier hospital discharge, a reduction or delay in long-term care admissions, and an improvement in mortality and other disease-specific patient outcomes.

OHTAC approved the development of an evidence-based assessment to determine the effectiveness of specialized community based care for the management of heart failure, Type 2 diabetes and chronic wounds.

Please visit the Medical Advisory Secretariat Web site at: www.health.gov.on.ca/ohtas to review the following reports associated with the Specialized Multidisciplinary Community-Based care series.

Specialized multidisciplinary community-based care series: a summary of evidence-based analyses

Community-based care for the specialized management of heart failure: an evidence-based analysis

Community-based care for chronic wound management: an evidence-based analysis

Please note that the evidence-based analysis of specialized community-based care for the management of diabetes titled: “Community-based care for the management of type 2 diabetes: an evidence-based analysis” has been published as part of the Diabetes Strategy Evidence Platform at this URL: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/mas/tech/ohtas/tech_diabetes_20091020.html

Please visit the Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment Collaborative Web site at: http://theta.utoronto.ca/papers/MAS_CHF_Clinics_Report.pdf to review the following economic project associated with this series:

Community-based Care for the specialized management of heart failure: a cost-effectiveness and budget impact analysis.

Objective

The objective of this evidence-based review is to determine the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary wound care team for the management of chronic wounds.

Clinical Need: Condition and Target Population

Chronic wounds develop from various aetiologies including pressure, diabetes, venous pathology, and surgery. A pressure ulcer is defined as a localized injury to the skin/and or underlying tissue occurring most often over a bony prominence and caused, alone or in combination, by pressure, shear, or friction. Up to three fifths of venous leg ulcers are due to venous aetiology.

Approximately 1.5 million Ontarians will sustain a pressure ulcer, 111,000 will develop a diabetic foot ulcer, and between 80,000 and 130,000 will develop a venous leg ulcer. Up to 65% of those afflicted by chronic leg ulcers report experiencing decreased quality of life, restricted mobility, anxiety, depression, and/or severe or continuous pain.

Multidisciplinary Wound Care Teams

The term ‘multidisciplinary’ refers to multiple disciplines on a team and ‘interdisciplinary’ to such a team functioning in a coordinated and collaborative manner. There is general consensus that a group of multidisciplinary professionals is necessary for optimum specialist management of chronic wounds stemming from all aetiologies. However, there is little evidence to guide the decision of which professionals might be needed form an optimal wound care team.

Evidence-Based Analysis Methods

Literature Search

A literature search was performed on July 7, 2009 using OVID MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, OVID EMBASE, Wiley Cochrane, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination/International Agency for Health Technology Assessment, and on July 13, 2009 using the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and the International Agency for Health Technology Assessment (INAHTA) for studies pertaining to leg and foot ulcers. A similar literature search was conducted on July 29’ 2009 for studies pertaining to pressure ulcers. Abstracts were reviewed by a single reviewer and, for those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, full-text articles were obtained. Reference lists were also examined for any additional relevant studies not identified through the search. Articles with an unknown eligibility were reviewed with a second clinical epidemiologist and then a group of epidemiologists until consensus was established.

Inclusion Criteria

Randomized controlled trials and Controlled clinical Trials (CCT)

Systematic review with meta analysis

Population includes persons with pressure ulcers (anywhere) and/or leg and foot ulcers

The intervention includes a multidisciplinary (two or more disciplines) wound care team.

The control group does not receive care by a wound care team

Studies published in the English language between 2004 and 2009

Exclusion Criteria

Single centre retrospective observational studies

Outcomes of Interest

Proportion of persons and/or wounds completely healed

Time to complete healing

Quality of Life

Pain assessment

Summary of Findings

Two studies met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, one a randomized controlled trial (RCT), the other a CCT using a before and after study design. There was variation in the setting, composition of the wound care team, outcome measures, and follow up periods between the studies. In both studies, however, the wound care team members received training in wound care management and followed a wound care management protocol.

In the RCT, Vu et al. reported a non-significant difference between the proportion of wounds healed in 6 months using a univariate analysis (61.7% for treatment vs. 52.5% for control; p=0.074, RR=1.19) There was also a non-significant difference in the mean time to healing in days (82 for treatment vs. 101 for control; p=0.095). More persons in the intervention group had a Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) score equal to zero (better pain control) at 6 months when compared with the control group (38.6% for intervention vs. 24.4% for control; p=0.017, RR=1.58). By multivariate analysis a statistically significant hazard ratio was reported in the intervention group (1.73, 95% CI 1.20-1.50; p=0.003).

In the CCT, Harrison et al. reported a statistically significant difference in healing rates between the pre (control) and post (intervention) phases of the study. Of patients in the pre phase, 23% had healed ulcers 3 months after study enrolment, whereas 56% were healed in the post phase (P<0.001, OR=4.17) (Figure 3). Furthermore, 27% of patients were treated daily or more often in the pre phase whereas only 6% were treated at this frequency in the post phase (P<0.001), equal to a 34% relative risk reduction in frequency of daily treatments. The authors did not report the results of pain relief assessment.

The body of evidence was assessed using the GRADE methodology for 4 outcomes: proportion of wounds healed, proportion of persons with healed wounds, wound associated pain relief, and proportion of persons needing daily wound treatments. In general, the evidence was found to be low to very low quality.

Conclusion

The evidence supports that managing chronic wounds with a multidisciplinary wound care team significantly increases wound healing and reduces the severity of wound-associated pain and the required daily wound treatments compared to persons not managed by a wound care team. The quality of evidence supporting these outcomes is low to very low meaning that further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Background

In August 2008, the Medical Advisory Secretariat (MAS) presented a vignette to the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC) on a proposed targeted health care delivery model for chronic care. The proposed model was defined as multidisciplinary, ambulatory, community-based care that bridged the gap between primary and tertiary care, and was intended for individuals with a chronic disease who were at risk of a hospital admission or emergency department visit. The goals of this care model were thought to include: the prevention of emergency department visits, a reduction in hospital admissions and re-admissions, facilitation of earlier hospital discharge, a reduction or delay in long-term care admissions, and an improvement in mortality and other disease-specific patient outcomes.

OHTAC approved the development of an evidence-based assessment to determine the effectiveness of specialized community based care for the management of heart failure, Type 2 diabetes and chronic wounds.

Please visit the Medical Advisory Secretariat Web site at: www.health.gov.on.ca/ohtas to review the following reports associated with the Specialized Multidisciplinary Community-Based care series.

Specialized multidisciplinary community-based care series: a summary of evidence-based analyses

Community-based care for the specialized management of heart failure: an evidence-based analysis

Community-based care for chronic wound management: an evidence-based analysis

Please note that the evidence-based analysis of specialized community-based care for the management of diabetes titled: “Community-based care for the management of type 2 diabetes: an evidence-based analysis” has been published as part of the Diabetes Strategy Evidence Platform at this URL: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/mas/tech/ohtas/tech_diabetes_20091020.html

Please visit the Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment Collaborative Web site at: http://theta.utoronto.ca/papers/MAS_CHF_Clinics_Report.pdf to review the following economic project associated with this series:

Community-based Care for the specialized management of heart failure: a cost-effectiveness and budget impact analysis.

Objective of Analysis

The objective of this evidence-based review is to determine the effectiveness of multidisciplinary care for the management of chronic wounds.

Clinical Need and Target Population

Chronic wounds develop from various aetiologies including pressure, diabetes, venous pathology and surgery. Without adequate management, they pose a significant risk to patient safety and may result in infection, limb loss, sepsis, and possibly death. Community-care nursing services are often required to care for pressure ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers, venous leg ulcers, and non-healing surgical wounds. (1)

A pressure ulcer is defined as a localized injury to the skin/and or underlying tissue occurring most often over a bony prominence and caused, alone or in combination, by pressure, shear, or friction. Up to 65% of those afflicted by chronic leg ulcers report experiencing decreased quality of life, restricted mobility, anxiety, depression, and/or severe or continuous pain. (2) Those most at risk for developing pressure ulcers include the elderly and critically ill, as well as persons with neurological impairments and others who suffer from conditions associated with immobility.

Prevalence and Incidence

The prevalence of pressure ulcers in Canadian health care facilities is estimated to be 25% in acute care, 29.9% in non-acute care, 22.1% in mixed healthcare settings, and 15.1% in community care. (3) The estimated cost to care for a pressure ulcer in the community is $27,000 Cdn. Moreover, approximately 15% of diabetics will develop a foot ulcer in their lifetime and 14% to 24% of these people will require amputation. (1) The average total cost per amputation in Ontario ranges from $40,000 to &74,000. (1) The prevalence of venous leg ulcers ranges from 0.8% to 1.3% in the general population, and 2% in those over 65 years of age. If effective prevention strategies are not put in place post healing, the recurrence rate is approximately 70%. (1)

Ontario Prevalence and Incidence

Given the prevalence rates cited above, it can be expected that approximately 1.5 million Ontarians will sustain a pressure ulcer, 111,000 will develop a diabetic foot ulcer [based on an estimated 744,000 prevalent cases of diabetes type 2 in 2005 (4)] and between 80,000 and 130,000 will sustain a venous leg ulcer.

Multidisciplinary Wound Care Team

The term ‘multidisciplinary’ refers to multiple disciplines on a team, while ‘interdisciplinary’ refers to such a team functioning in a coordinated and collaborative manner. (5) There is general consensus that a group of multidisciplinary professionals is necessary for optimum specialist management of chronic wounds stemming from all aetiologies.(6) However, there is little evidence to guide the decision of which professionals might be needed to form an optimal wound care team.

Evidence-Based Analysis

Research Question(s)

The purpose of this systematic review is to determine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a community based multidisciplinary wound care team for the management of chronic wounds.

Methods

Literature Search

A literature search was performed on July 7, 2009 using OVID MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, OVID EMBASE, Wiley Cochrane, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination/International Agency for Health Technology Assessment, and on July 13, 2009 using the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and the International Agency for Health Technology Assessment (INAHTA) for studies pertaining to leg and foot ulcers. A similar literature search was conducted on July 29, 2009 for studies pertaining to pressure ulcers. Details of the search strategies are reported in Appendix 1.

Abstracts were reviewed by a single reviewer and, for those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, full-text articles were obtained. Reference lists were also examined for any additional relevant studies not identified through the search. Articles with an unknown eligibility were reviewed with a second clinical epidemiologist and then a group of epidemiologists until consensus was established.

Inclusion Criteria

Randomized controlled trials and Controlled clinical Trials (CCT)

Systematic review with meta analysis

Population includes persons with pressure ulcers (anywhere) and/or leg and foot ulcers

The intervention includes a multidisciplinary (two or more disciplines) wound care team.

The control group does not receive care by a wound care team

Studies published in the English language between 2004 and 2009

Exclusion Criteria

Single centre retrospective observational studies

Outcomes of Interest

Proportion of persons and/or wounds completely healed

Time to complete healing

Quality of Life

Pain assessment

Statistical Analysis

Where appropriate, a meta-analysis was undertaken to determine the pooled estimate of effect of specialized multidisciplinary community-based care for explicit outcomes.

Quality of Evidence

The quality of the body of evidence was assessed as high, moderate, low, or very low according to the GRADE Working Group criteria as presented below. (7)

Quality refers to the criteria such as the adequacy of allocation concealment, blinding and follow-up.

Consistency refers to the similarity of estimates of effect across studies. If there are important and unexplained inconsistencies in the results, our confidence in the estimate of effect for that outcome decreases. Differences in the direction of effect, the magnitude of the difference in effect, and the significance of the differences guide the decision about whether important inconsistency exists.

Directness refers to the extent to which the interventions and outcome measures are similar to those of interest.

As stated by the GRADE Working Group, the following definitions of quality were used in grading the quality of the evidence:

| High | Further research is very unlikely to change the confidence in the estimate of effect. |

| Moderate | Further research is likely to have an important impact on confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. |

| Low | Further research is very likely to have an important impact on confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. |

| Very Low | Any estimate of effect is very uncertain |

Results of Evidence-Based Analysis

Included studies

The literature search yielded 1,367 citations of which 37 full-text articles were obtained. Of these, two met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, one randomized controlled trial (RCT) and a CCT using a ‘before and after’ study design. Table 1 reports the quality of evidence by study design included in this report (8). Tables 2 and 3 report the characteristics and design models of the included studies.

Table 1: Quality of Evidence of Included Studies (Table Title).

| Study Design | Level of Evidence† |

Number of Eligible Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Large RCT, systematic review of RCTs | 1 | |

| Large RCT unpublished but reported to an international scientific meeting | 1(g) | |

| Small RCT | 2 | 1 |

| Small RCT unpublished but reported to an international scientific meeting | 2(g) | |

| Non-RCT with contemporaneous controls | 3a | 1 |

| Non-RCT with historical controls | 3b | |

| Non-RCT presented at international conference | 3(g) | |

| Surveillance (database or register) | 4a | |

| Case series (multisite) | 4b | |

| Case series (single site) | 4c | |

| Retrospective review, modelling | 4d | |

| Case series presented at international conference | 4(g) | |

| Total | 2 |

RCT refers to randomized controlled trial;

Table 2: Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Author, Year | Country | Study Design | Sample Size (n) | Mean Age (years) | Type of Wound |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harrison et al, 2005 (10) | Canada | Before/After | Before: 78 After: 180 |

73 | Leg ulcers below the knee, without arterial involvement |

| Vu et al, 2007 (9) | Australia | RCT | 44 nursing homes, 176 residents (342 wounds) Intervention 21 nursing homes, 94 residents (180 wounds) Control 23 nursing homes, 82 residents (162 wounds) |

83 | 25% leg ulcer 75% pressure ulcer |

Table 3: Design Details of Included Studies.

| Author, Year | Population | Intervention and Time to Follow Up |

Outcome Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harrison et al, 2005 (10) |

|

|

Primary:

Secondary:

|

| Vu et al, 2007 (9) |

|

|

Primary:

Secondary:

|

There was variation in the setting, composition of the wound care team, outcome measure, and follow up period between the studies. Specifically:

Vu et al. (9) evaluated a wound care team comprised of a community pharmacist and a nurse to manage leg and pressure ulcers in a nursing home setting.

Harrison et al. (10) evaluated the effectiveness of a wound care team comprised primarily of nurses to manage leg ulcers in a community setting.

While the outcome measures were similar between studies, insofar as they included healing rates and pain management, the assessment methods differed for each of these outcomes between studies. Vu et al. (9) reported the proportion of wounds healed at 6 months while Harrison et al. (10) reported the proportion of persons with a healed wound at 3 months. Different methods were also used to assess wound associated pain with Vu et al.(9) using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) and Harrison et al. using the Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire. In both studies the wound care team members received training in wound care management and followed a wound care management protocol.

Individual Study Quality Assessment

The individual study quality assessment for each of the included studies is reported in Appendix 2. Vu et al. (9) designed an RCT but failed to use appropriate methods of randomization. Randomization was done at the nursing home level with nursing homes allocated alternately to either treatment or control groups and because of this, there was inadequate allocation concealment. There was also an imbalance in baseline characteristics between groups with wounds in the intervention group more likely to be severe based on mean width and the proportion with moderate or profuse exudate, to be present for less than 1 week at the time of enrolment (age of wound), more painful. Persons in the intervention group were also significantly underweight compared to the control group. Blinding of the outcome assessors was also not followed. Harrison et al. (10) completed a before and after study. Methodological limitations of this study include that the outcome measure was not done independently of the exposure status and an imbalance in the baseline characteristics between the pre and the post phase with more venous leg ulcers in the post phase group than were in the pre phase group. There was also an imbalance in the sample size between treatment phases with 78 persons enrolled in the pre phase and more than twice that (180) in the post phase of the study.

Outcomes

As mentioned previously, the outcome measures between studies included wound healing rate and adequacy of wound-associated pain management. Vu et al. (9) reported the proportion of wounds healed and assessed pain relief using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), an 11-point (0-10) numeric scale. Whereas Harrison et al. (10) reported the proportion of persons with a healed ulcer and used the Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire.

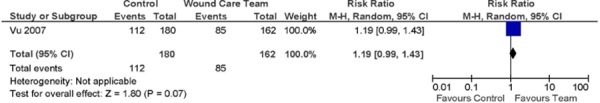

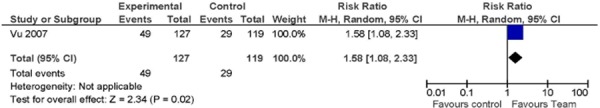

Vu et al. (9) reported a non-significant difference between the proportion of wounds healed in 6 months using a univariate analysis (61.7% for treatment vs. 52.5% for control; p=0.074, RR=1.19) (Figure 1). There was also a non-significant difference in the mean time to healing in days (82 for treatment vs. 101 for control; p=0.095). There was, however, a statistically significant difference in total pain relief between groups. More persons in the intervention group had a BPI score equal to zero at 6 months when compared with the control group (38.6% for intervention vs. 24.4% for control; p=0.017, RR=1.58) (Figure 2). When a multivariate analysis was undertaken, Vu et al. (9) reported significant differences in the relative risk between treatment and control groups (RR 1.73, 95% CI 1.2-2.5; p=.003) indicating a 73% chance of wounds healing in the intervention (team care) group compared to the control (non team care) group

Figure 1: Proportion of Healed Wounds.

Figure 2: Proportion of Persons with a BPI score = 0.

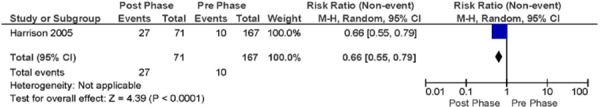

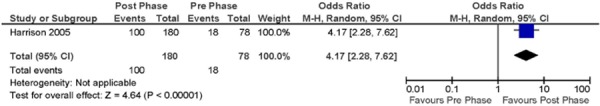

Harrison et al. (10) reported a statistically significant difference in healing rates between the pre (control) and post (intervention) phases of the study. Twenty three (23%) percent of patients in the pre phase had healed ulcers 3 months after study enrolment, whereas 56% were healed in the post phase (P<0.001, OR=4.17) (Figure 3). Both venous and mixed disease ulcers showed significant healing rates in the post phase compared to the pre phase. There was also a reduction in the treatment frequency in the post phase compared to the pre phase. Twenty-seven (27%) percent of patients were treated daily or more often in the pre phase whereas only 6% were treated at this frequency in the post phase (P<0.001) equal to a 34% relative risk reduction in frequency of daily treatments (Figure 4). The authors did not report the results of pain relief assessment.

Figure 3: Proportion of Persons with Healed Wounds.

Figure 4: Proportion of Persons needing daily wound treatments.

GRADE Quality Evidence

The body of evidence was assessed using the GRADE methodology for four outcomes:

proportion of wounds healed,

proportion of persons with healed wounds,

wound associated pain relief, and

proportion of persons needing daily wound treatments.

The Grade evidence profile for each of these outcomes is presented in Table 4. In general, the evidence was found to be low to very low quality.

Table 4: Grade Evidence Profiles.

| Quality Assessment | Summary of Findings | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of Patients | Effect | ||||||||||

| No of studies | Design | Limitations | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Wound Care Team | Usual Care | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | Quality |

| Proportion of Wounds Healed (follow-up 6 months; Proportion of wounds healed) | |||||||||||

| 11 | randomised trials | serious2 | no serious inconsistency | serious3 | serious4 | none |

112/180 (62.2%) |

85/162 (52.5%) |

RR 1.19 (0.99 to 1.43) | 100 fewer per 1000 (from 5 fewer to 226 more) | ⊕ΟΟΟ VERY LOW |

| Proportion of Persons with wounds healed (follow-up mean 3 months) | |||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies5 | serious6 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious7 | strong association8 |

100/180 (55.6%) |

18/78 (23.1%) |

OR 4.17 (2.28 to 7.62) | 325 more per 1000 (from 175 more to 465 more) | ⊕ΟΟΟ VERY LOW |

| Persons with BPI score=0 (follow-up mean 6 months; Brief Pain Inventory9) | |||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials1 | serious2 | no serious inconsistency | serious3 | serious4 | none |

49/127 (38.6%) |

29/119 (24.4%) |

RR 1.58 (1.08 to 2.33) | 141 more per 1000 (from 19 more to 324 more) | ⊕ΟΟΟ VERY LOW |

| Proportion of Persons needing daily treatments (follow-up mean 3 months) | |||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials1 | serious2 | no serious inconsistency | serious3 | serious4 | none |

49/127 (38.6%) |

29/119 (24.4%) |

RR 1.58 (1.08 to 2.33) | 141 more per 1000 (from 19 more to 324 more) | ⊕ΟΟΟ VERY LOW |

One Study by Vu et al. 2007

Alternating randomization, lack of allocation concealment

Nursing Home setting not a community-based study

Sparse data, one small study

One study by Harrison et al. 2005

Outcome measure not assessed independent of the exposure status

One study contributing to body of evidence therefore considered sparse data

Relative odds reduction of 76%

9 11-point scale (0-10) to assess wound-associated pain

Economic Analysis

An Ontario-based economic analysis ad budget impact could not be completed because of the low quality of evidence supporting the effectiveness of a wound care team.

Conclusion

The evidence supports that managing chronic wounds with a multidisciplinary wound care team significantly increases wound healing. The evidence also supports that the management of wounds by a multidisciplinary wound care teams reduce the severity of wound-associated pain and required daily wound treatments. The quality of evidence supporting these outcomes is low to very low, meaning that further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Literature Search Strategies

Final Leg and Foot Ulcer Search – Multidisciplinary Care

Search date: July 7, 2009

Databases searched: OVID MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, OVID EMBASE, Wiley Cochrane, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination/International Agency for Health Technology Assessment

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1996 to June Week 4 2009>

Search Strategy:

exp Patient Care Team/ (23639)

exp Nursing, Team/ (658)

exp Cooperative Behavior/ (13868)

exp Interprofessional Relations/ (22628)

team*.ti,ab. (37084)

(integrat$ or share or shared or sharing).ti,ab. (186507)

(multidisciplin$ or multi-disciplin$ or interdisciplin$ or inter-disciplin$ or collaborat$ or cooperat$ or cooperat$ or multi?special$ or interprofessional* or intra-professonal* or interprofessional* or intraprofessional*).ti,ab. (102255)

or/1-7 (334716)

exp Leg Ulcer/ or exp Diabetic Foot/ (7493)

exp Lymphedema/ (2842)

((leg* or foot* or feet or stasis or venous or varicose or arterial or diabet* or ischemic) adj2 (ulcer* or wound* or sore*)).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word] (7066)

lymphedema.mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word] (2417)

((leg* or foot or feet) adj2 (edema or oedema)).ti,ab. (447)

or/9-12 (12289)

8 and 14 (774)

limit 15 to (english language and humans and yr=“2005 - 2009”) (241)

Database: EMBASE <1980 to 2009 Week 27>

Search Strategy:

exp TEAM NURSING/ (44)

exp Cooperation/ (28829)

exp TEAMWORK/ or team*.ti,ab. (49616)

(integrat$ or share or shared or sharing).ti,ab. (221410)

(multidisciplin$ or multi-disciplin$ or interdisciplin$ or inter-disciplin$ or collaborat$ or cooperat$ or cooperat$ or multi?special$ or interprofessional* or intra-professonal* or interprofessional* or intraprofessional*).ti,ab. (124270)

or/1-5 (381895)

exp Leg Ulcer/ (11145)

exp foot ulcer/ or exp leg ulcer/ or exp plantar ulcer/ or exp leg varicosis/ or *diabetic foot/ or exp *leg edema/ (30203)

((leg* or foot* or feet or stasis or venous or varicose or ischemic or arterial or diabet*) adj2 (ulcer* or wound* or sore*)).ti,ab. (7203)

((leg* or foot or feet) adj2 (edema or oedema)).ti,ab. (716)

or/7-10 (32794)

exp venous stasis/ or exp lymphedema/ (8322)

exp Leg/ or exp Foot/ (52228)

12 and 13 (454)

11 or 14 (33147)

6 and 15 (886)

limit 16 to (human and english language and yr=“2005 - 2009”) (269)

Multidisciplinary Care – Leg and Foot Ulcers – CINAHL Search Strategy

Monday, July 13, 2009

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| S14 | s13 | 231 |

| S13 | S6 and S12 | 542 |

| S12 | S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 | 7033 |

| S11 | leg edema or foot edema or lymphedema or leg oedema or foot oedema | 1,043 |

| S10 | leg* ulcer* or foot* ulcer* or feet ulcer* or stasis ulcer* or venous ulcer* or varicose ulcer* or arterial ulcer* or diabet* ulcer* or ischemic ulcer* | 4,141 |

| S9 | (MH “Lymphedema+”) | 971 |

| S8 | (MH “Diabetic Foot”) | 2,970 |

| S7 | (MH “Leg Ulcer+”) | 5,650 |

| S6 | S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 | 124,190 |

| S5 | integrat* or team* or share or shared or sharing or multidisciplin* or multi-disciplin* or interdisciplin* or inter-disciplin* or collaborat* or cooperat* or co-operat* or multi-special* or multispecial* or interprofessional* or inter-professional or intra-professonal* or interprofessional* or intraprofessional* | 122, 154 |

| S4 | (MH “Interprofessional Relations+”) | 11,048 |

| S3 | (MH “Cooperative Behavior”) | 1,719 |

| S2 | (MH “Team Nursing”) | 299 |

| S1 | (MH “Multidisciplinary Care Team+”) | 13,992 |

Final Search – Pressure Ulcers – Multidisciplinary Care

Search date: July 20, 2009

Databases searched: OVID MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, OVID EMBASE, Wiley Cochrane, CINAHL, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination/International Agency for Health Technology Assessment

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1950 to July Week 2 2009>

Search Strategy:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

exp Patient Care Team/ (43358)

exp Nursing, Team/ (1798)

exp Cooperative Behavior/ (15940)

exp Interprofessional Relations/ (41288)

team*.ti,ab. (58145)

(integrat$ or share or shared or sharing).ti,ab. (278305)

(multidisciplin$ or multi-disciplin$ or interdisciplin$ or inter-disciplin$ or collaborat$ or cooperat$ or cooperat$ or multi?special$ or interprofessional* or intra-professonal* or interprofessional* or intraprofessional*).ti,ab. (161442)

or/1-7 (526197)

exp Pressure Ulcer/ (7915)

((bed or pressure or decubit*) adj2 (sore* or ulcer* or wound*)).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word] (10488)

bedsore*.mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word] (298)

or/9-11 (10565)

8 and 12 (659)

limit 13 to (english language and humans and yr=“2004 -Current”) (203)

Database: EMBASE <1980 to 2009 Week 29>

Search Strategy:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

exp TEAM NURSING/ (11)

exp Cooperation/ (13977)

exp TEAMWORK/ or team*.ti,ab. (43431)

(integrat$ or share or shared or sharing).ti,ab. (221977)

(multidisciplin$ or multi-disciplin$ or interdisciplin$ or inter-disciplin$ or collaborat$ or cooperat$ or cooperat$ or multi?special$ or interprofessional* or intra-professonal* or interprofessional* or intraprofessional*).ti,ab. (124516)

or/1-5 (369073)

exp Decubitus/ (4335)

((bed or pressure or decubit*) adj2 (sore* or ulcer* or wound*)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name] (4870)

bedsore*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name] (168)

or/7-9 (6243)

6 and 10 (371)

limit 11 to (human and english language and yr=“2004 -Current”) (148)

CINAHL

| # | Query | Limiters/Expanders | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| S11 | S10 | Limiters - Published Date from: 01/2004-12/2009 | 275 |

| S10 | S6 and S9 | 2 | |

| S9 | S7 or S8 | 71 | |

| S8 | bedsore* or bed sore* or pressure ulcer* or decubit* or pressure wound* | 6,886 | |

| S7 | (MH “Pressure Ulcer”) | 5,904 | |

| S6 | S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 | 1,498 | |

| S5 | integrat* or team* or share or shared or sharing or multidisciplin* or multi-disciplin* or interdisciplin* or inter-disciplin* or collaborat* or cooperat* or co-operat* or multi-special* or multispecial* or interprofessional* or inter-professional or intra-professonal* or interprofessional* or intraprofessional* | 122,601 | |

| S4 | (MH “Interprofessional Relations+”) | 11,086 | |

| S3 | (MH “Cooperative Behavior”) | 1,722 | |

| S2 | (MH “Team Nursing”) | 300 | |

| S1 | (MH “Multidisciplinary Care Team+”) | 14,053 |

Appendix 2: Individual Study Assessment

Table: Quality assessment for Vu et al. 2007 (9).

| Study | Design | N | Adequate randomization methods | Baseline characteristics comparable | Adequate Allocation Concealment | Blinding of outcome assessors | Sample Size Calculation | Losses to Follow up (%) | #ITT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vu et al, 2007 (11) | RCT | 83 | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | 3.2% | ✓ |

| Except for severity, age of wound and level of pain and weight. |

Table: Quality assessment for Harrison et al. 2005 (10).

| Study | Design | Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria Stated | Consecutive Sampling Used | Similar Baseline Characteristics in Groups? | Treatment Valid and Reliable? | Reliable and Valid Outcome Measure Used? | Outcome Measure Done Independently of Exposure Status? | Duration of Follow-Up Adequate? | Loss to Follow-Up, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harrison et al. 2005 (10) | Observational Before/After | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ Except for cause of leg ulcers. Great number of venous disease leg ulcers in new model than in old mode. |

✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ | 8% 10 % in before phase 7% in after phase |

Suggested Citation

This report should be cited as follows:

Medical Advisory Secretariat. Community-based care for chronic wound management: an evidence-based analysis. Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series 2009; 9(18).

Permission Requests

All inquiries regarding permission to reproduce any content in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series should be directed to MASinfo.moh@ontario.ca.

How to Obtain Issues in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series

All reports in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are freely available in PDF format at the following URL: www.health.gov.on.ca/ohtas.

Print copies can be obtained by contacting MASinfo.moh@ontario.ca.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All analyses in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are impartial and subject to a systematic evidence-based assessment process. There are no competing interests or conflicts of interest to declare.

Peer Review

All Medical Advisory Secretariat analyses are subject to external expert peer review. Additionally, the public consultation process is also available to individuals wishing to comment on an analysis prior to finalization. For more information, please visit http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/ohtac/public_engage_overview.html.

Contact Information

The Medical Advisory Secretariat

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

20 Dundas Street West, 10th floor

Toronto, Ontario

CANADA

M5G 2N6

Email: MASinfo.moh@ontario.ca

Telephone: 416-314-1092

ISSN 1915-7398 (Online)

ISBN 978-1-4435-1407-1 (PDF)

About the Medical Advisory Secretariat

The Medical Advisory Secretariat is part of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. The mandate of the Medical Advisory Secretariat is to provide evidence-based policy advice on the coordinated uptake of health services and new health technologies in Ontario to the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and to the healthcare system. The aim is to ensure that residents of Ontario have access to the best available new health technologies that will improve patient outcomes.

The Medical Advisory Secretariat also provides a secretariat function and evidence-based health technology policy analysis for review by the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC).

The Medical Advisory Secretariat conducts systematic reviews of scientific evidence and consultations with experts in the health care services community to produce the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series.

About the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series

To conduct its comprehensive analyses, the Medical Advisory Secretariat systematically reviews available scientific literature, collaborates with partners across relevant government branches, and consults with clinical and other external experts and manufacturers, and solicits any necessary advice to gather information. The Medical Advisory Secretariat makes every effort to ensure that all relevant research, nationally and internationally, is included in the systematic literature reviews conducted.

The information gathered is the foundation of the evidence to determine if a technology is effective and safe for use in a particular clinical population or setting. Information is collected to understand how a new technology fits within current practice and treatment alternatives. Details of the technology’s diffusion into current practice and input from practising medical experts and industry add important information to the review of the provision and delivery of the health technology in Ontario. Information concerning the health benefits; economic and human resources; and ethical, regulatory, social and legal issues relating to the technology assist policy makers to make timely and relevant decisions to optimize patient outcomes.

If you are aware of any current additional evidence to inform an existing evidence-based analysis, please contact the Medical Advisory Secretariat: MASinfo.moh@ontario.ca. The public consultation process is also available to individuals wishing to comment on an analysis prior to publication. For more information, please visit http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/ohtac/public_engage_overview.html.

Disclaimer

This evidence-based analysis was prepared by the Medical Advisory Secretariat, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, for the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee and developed from analysis, interpretation, and comparison of scientific research and/or technology assessments conducted by other organizations. It also incorporates, when available, Ontario data, and information provided by experts and applicants to the Medical Advisory Secretariat to inform the analysis. While every effort has been made to reflect all scientific research available, this document may not fully do so. Additionally, other relevant scientific findings may have been reported since completion of the review. This evidence-based analysis is current to the date of publication. This analysis may be superseded by an updated publication on the same topic. Please check the Medical Advisory Secretariat Website for a list of all evidence-based analyses: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/ohtas.

List of Abbreviations

- CCT

Confidence interval(s)

- MAS

Medical Advisory Secretariat

- OR

Odds ratio

- OHTAC

Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- RR

Relative risk

- SD

Standard deviation

- CI

Confidence Interval

References

- 1.Campbell K, Teague L, Hurd T, King J. Health policy and the delivery of evidence-based wound care using regional wound teams. Healthc Manage Forum. 2006;19(2):16–21. doi: 10.1016/S0840-4704(10)60818-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards H, Courtney M, Finlayson K, Shuter P, Lindsay E. A randomised controlled trial of a community nursing intervention: improved quality of life and healing for clients with chronic leg ulcers. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(11):1541–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodbury MG, Houghton PE. Prevalence of pressure ulcers in Canadian healthcare settings. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004;50(10):22–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medical Advisory Secretariat. Community programs for the management of type 2 diabetes: an evidence-based analysis. Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series. 2009;9(10) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dailey M. Interdisciplinary collaboration: essential for improved wound care outcomes and wound prevention in home care. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2005;17(3):213–21. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Game FL. The advantages and disadvantages of non-surgical management of the diabetic foot. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(SUPPL. 1):S72–S75. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodman C. Literature searching and evidence interpretation for assessing health care practices. Stockholm, Sweden: The Swedish council on Technology Assessment in Health Care. 1993. p. 32 p. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Vu T, Harris A, Duncan G, Sussman G. Cost-effectiveness of multidisciplinary wound care in nursing homes: A pseudo-randomized pragmatic cluster trial. Fam Pract. 2007;24(4):372–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmm024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison MB, Graham ID, Lorimer K, Friedberg E, Pierscianowski T, Brandys T. Leg-ulcer care in the community, before and after implementation of an evidence-based service. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;172(11):1447–52. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison MB, Graham ID, Lorimer K, Vandenkerkhof E, Buchanan M, Wells PS, et al. Nurse clinic versus home delivery of evidence-based community leg ulcer care: a randomized health services trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:243. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]