Abstract

The selective two-electron reduction of O2 by one-electron reductants such as decamethylferrocene (Fc*) and octamethylferrocene (Me8Fc) is efficiently catalyzed by a binuclear Cu(II) complex ([CuII2(LO)(OH)]2+ (D1) {LO is a binucleating ligand with copper-bridging phenolate moiety} in the presence of trifluoroacetic acid (HOTF) in acetone. The protonation of the hydroxide group of [CuII2(LO)(OH)]2+ with HOTF to produce [CuII2(LO)(OTF)]2+ (D1-OTF) makes it possible for this to be reduced by two equiv of Fc* via a two-step electron transfer sequence. Reactions of the fully reduced complex [CuI2(LO)]+ (D3) with O2 in the presence of HOTF led to the low-temperature detection of the absorption spectra due to the peroxo complex ([CuII2(LO)(OO)]) (D) and the protonated hydroperoxo complex ([CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4). No further Fc* reduction of D4 occurs, and it is instead further protonated by HOTF to yield H2O2 accompanied by regeneration of [CuII2(LO)(OTF)]2+ (D1-OTF) thus completing the catalytic cycle for the two-electron reduction of O2 by Fc*. Kinetic studies on the formation of Fc*+ under catalytic conditions as well as for separate examination of the electron transfer from Fc* to D1-OTF reveal there are two important reaction pathways operating. One is a rate-determining second reduction of D1-OTF, thus electron transfer from Fc* to a mixed-valent intermediate [CuIICuI(LO)]2+ (D2) which leads to [CuI2(LO)]+ which is coupled with O2 binding to produce [CuII2(LO)(OO)]+ (D). The other involves direct reaction of O2 with the mixed-valent compound D2 followed by rapid Fc* reduction of a putative superoxo-dicopper(II) species thus formed, producing D.

Introduction

Copper proteins which are involved in dioxygen (O2) processing1 possess highly evolved active-site environments, thus optimized via ligation with appropriate atom type (e.g., N, O, S), ligand charge (e.g., RS- vs. RSR’), the number of donors and their juxtaposition, resulting steric factors and second coordination shell influences,2 all leading to the generation of specific Cun(O2) (n = typically 1–3) structures suitable for a particular function.1f,3 The latter include O2-transport (CuI2 + O2 ⇄ Cu2(O2) and substrate oxygenation (R-H → R-OH).4 Another major class are copper oxidases, those effecting two-electron substrate oxidations (galactose oxidases;5 amine oxidases)6 while reducing O2 to H2O2.7 Meanwhile, multicopper oxidases (MCO’s)1a,1c,8 and heme-copper oxidases (HCO’s)9 facilitate 4e−/4H+ reduction of dioxygen to water; the latter reactivity is analogously a fuel cell reaction.10–16

The ligand environment also defines the resulting chemistry for copper(I)-O2 complexes, and dramatic tuning of O2-adduct structure and reactivity may come via a change in chelate ligand denticity. Tetradentate nitrogen based ligands typically provide for μ-1,2-peroxodicopper(II) adducts (A), tridentate chelates generally lead to side-on bound (μ-η2: η2)peroxo dicopper(II) complexes (B) and other tridentate or bidentate ligands support the formation of bis(μ-oxo)dicopper(III) CuIII2-(O)2 complexes (C) (Scheme 1).1f,3

Scheme 1.

We recently became interested in examining discrete copper complexes as catalysts for 4e−/4H+ O2-reduction to water.15,17 There is considerable interest in such catalysis, not only to aid the elucidation of fundamental principles relevant to biological processes (as above), but also due to the technological significance such as in fuel cell applications.10–16,18 In fact, we found that ligand-(di)copper complexes forming A, B or C (Scheme 1) can all catalyze the solution phase 4e−/4H+ O2-reduction to water, employing ferrocenes reductants and acids as proton sources.17 This methodology, as opposed to planting metal complexes onto electrode surfaces,10–16,18 enables reaction mechanism elucidation via solution kinetic and spectroscopic monitoring of key steps occurring and intermediates forming during catalysis.15,19–23

Thus, [{(TMPA)CuII}2(μ-1,2-O22−)]2+ (A1) (TMPA (tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine)) has structure A (Scheme 1) and when formed, it is reductively O–O cleavage (and protonated) to give water, that in preference to simple protonation leading to H2O2.17a,24 Precursor complexes leading to B or C are also catalysts for 4e−/4H+ reduction of O2.17b The course of reaction for [CuII2(N3)(H2O)2](ClO4)4 [B1; N3 = (-(CH2)3-linked bis[(2-(2-pyridyl)ethyl)amine]25 versus [CuII(BzPY1)(EtOH)](ClO4)2 [C1; BzPY1 = N,N-bis[2-(2-pyridyl)ethyl]benzylamine],26 differs.17b One important finding is that for B1, the observed intermediate species, [CuII2(N3)(μ-η2: η2-O22−)]2+, does not convert to the isomeric structure type C; rather, it is directly reduced by the ferrocenyl reductant leading to O–O cleavage to give water.

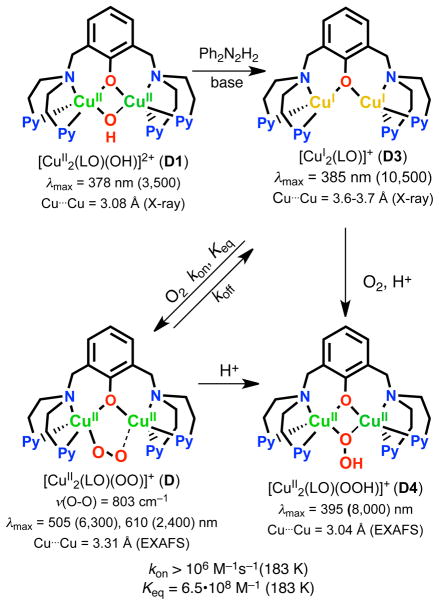

Thus far, there has been no report on the selective two-electron reduction of O2 to H2O2 by one-electron reductants using copper complex catalysts. Herein, we describe such a case involving dicopper complex chemistry giving a fourth known Cu2O2 structural type.27 A reduced species [CuI2(LO)]+ (D3) reacts with O2 to give [CuII2(LO)(OO)]+ (D),28 which possesses an ‘end-on’ peroxo-coordination (Scheme 2). The peroxo ligand in D is basic and facile protonation leads to the μ-1,1-hydroperoxo dicopper(II) complex [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4) (Scheme 2).29 As will be shown in this report, this step is one of the keys to providing the observation of overall catalytic two-electron two-proton reduction of dioxygen to hydrogen peroxide (eq 1):

| (1) |

Scheme 2.

Further, we have been able to dissect this catalytic process, confirming the reaction stoichiometry, elucidating its kinetic behavior and identifying various intermediates.

The insights obtained from this study and comparison to the 4e−/4H+ O2-reduction catalysis proceeding via O2-complexes A, B and C can or will allow us to explain how and why use of various ligands and their complexes lead to 4e−/4H+ O2-reduction while others (or at least one other) provides for 2e−/2H+ O2-reduction to H2O2. The basics obtained here should serve as useful and broadly applicable principles for future design of catalysts for use in substrate oxidations and/or fuel cells, H2O2 itself as a product having considerable potential utility. Hydrogen peroxide has attracted increasing attention as a promising candidate as a sustainable and clean energy carrier,30–33 because the free enthalpy change of the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide producing water and dioxygen is as large as −210.71 kJ mol−1,34 Hydrogen peroxide has also been used as a highly efficient and environmentally benign oxidant in terms of delignification efficiency and reducing ecological impact.35–36

Experimental Section

Materials

Grade quality solvents and chemicals were obtained commercially and used without further purification unless otherwise noted. Decamethylferrocene (Fc*) (97%), octamethylferrocene (Me8Fc), 1,1′-dimethylferrocene (Me2Fc), ferrocene (Fc), hydrogen peroxide (50%), and HOTF (99%) were purchased from Aldrich Co., USA, and NaI (99.5%) from Junsei Chemical Co., Japan. Acetone was purchased from JT Baker, USA and used whether without further purification for non-air-sensitive experiment or dried and distilled under argon then deoxygenated by bubbling with argon for 30–45 min and kept over activated molecular sieve (4 Å) for air-sensitive experiments.37 Preparation and handling of air-sensitive compounds were performed under Ar atmosphere (<1 ppm O2, <1 ppm H2O) in a glove box (Korea Kiyon Co., Ltd.). The copper complexes [CuI2(LH)(CH3CN)2](SbF6)2 (LH = m-xylene-linked bis[(2-(2-pyridyl)ethyl)amine]27 as a precursor to [CuII2(LO)(OH)](SbF6)2 (D1) and [CuI2(LO)]BArF (D3) (BArF− = B(C6F5)4−) for the low temperature generation of hydroperoxo species were prepared according to the literature procedures.29 The use of BArF− rather than SbF6− as counter-anion was due to the resulting higher stability and ease of handling of the air-sensitive dicopper(I) complex as well as the greater stability of the peroxo and hydroperoxo species that were then generated. Anal. Calcd. for (C36H40N6O2F12Cu2Sb2)•CH3CN: C, 37.15; H, 3.53; N, 7.98. Found: C, 37.24; H, 3.69; N, 8.32.

Instrumentation

UV-vis spectra were recorded on a Hewlett Packard 8453 diode array spectrophotometer equipped with a UNISOKU Scientific Instruments Cryostat USP-203A for low-temperature experiments or an UNISOKU RSP-601 stopped-flow spectrometer equipped with a MOS-type highly sensitive photodiode array. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) measurements were performed on an ALS 630B electrochemical analyzer and voltammograms were measured in deaerated acetone containing 0.20 M TBAPF6 as a supporting electrolyte at −40 °C. The temperature was controlled by use of an MeCN/liquid N2 bath. A conventional three-electrode cell was used with a gold working electrode (surface area of 0.3 mm2) and a platinum wire as the counter electrode. The Pt working electrode (BAS) was routinely polished with BAS polishing alumina suspension and rinsed with acetone before use. The potentials were measured with respect to the Ag/AgNO3 (0.010 M) reference electrode. All potentials (vs Ag/Ag+) were converted to values vs SCE by adding 0.29 V.38 All electrochemical measurements were carried out under an atmospheric pressure of nitrogen. X-band EPR spectra were recorded at 5 K using X-band Bruker EMX-plus spectrometer equipped with a dual mode cavity (ER 4116DM). Low temperature was achieved and controlled with an Oxford Instruments ESR900 liquid He quartz cryostat with an Oxford Instruments ITC503 temperature and gas flow controller. The experimental parameters for EPR spectra were as follows: Microwave frequency = 9.6483 GHz, microwave power = 1.0 mW, modulation amplitude = 10 G, gain = 5 × 102, modulation frequency = 100 kHz, time constant = 81.92 ms, and conversion time = 81.00 ms.

Kinetic Measurements

The spectral change in the UV-visible were recorded on a Hewlett Packard 8453 diode array spectrophotometer equipped with Unisoku thermostated cell holder for low-temperature experiments. In a typical catalytic reaction, the quartz cuvette is loaded with 3 mL of 10:30:1 Fc*/HOTF/D1 (1.0 × 10−4 M) in a degassed solution of acetone. Then O2 gas (99.999%) was introduced into the solution through a needle for 1 min to make it O2-saturated. The catalytic reaction is monitored by the increase in the absorbance at 780 nm corresponding to the formation of the ferrocenium cation (Fc*+) (ε = 5.8 × 102 M−1 cm−1). The ε value of Fc*+ was confirmed by the electron-transfer oxidation of Fc* with p-benzoquinone in the presence of HOTF (see Figure S1 in Supporting Information (SI)).

The limiting concentration of O2 in an acetone solution was prepared by injecting a different aliquots of an O2-saturated acetone solution (1.1 × 10−2 M),39 prepared by bubbling O2 through argon-saturated acetone in a Schlenk tube for 30 min at 298 K.40 In case of the experiment involving 2.2 equiv of O2 relative to D1 (1.0 × 10−4 M), 60 μL of the O2-saturated acetone solution were injected into the cuvette with the total volume of 3 mL.

Iodometric Titration for the Determination of H2O2

The amount of H2O2 was determined by titration with iodide ion.41 The diluted acetone solution (1/15) of the reduced product of O2 was treated with an excess of NaI. The amount of I3− formed was then quantified using its visible spectrum (λmax = 361 nm, ε = 2.5 × 104 M−1 cm−1). The controlled reactions including the reaction of D1 complex with NaI, H2O2 with NaI in the absence of D1 and H2O2 with NaI in the presence of D1 were also performed in order to elucidate the exact amount of H2O2 generated in the catalytic two electron reduction of O2 by Fc*.

Low Temperature Experiments Concerning the Generation of [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+

(D4) Under an argon atmosphere within a glove box, [CuI2(LO)]BArF (D3) (7.0 × 10−5 M) was dissolved in 3 mL of O2-free acetone giving a bright yellow solution. The cuvette was fully sealed with septum and quickly removed from the glove box and cooled to −80 °C in a Hewlett Packard 8453 diode array spectrophotometer equipped with Unisoku thermostated cell holder. O2 was gently bubbled through the reaction solution and 1 equiv HOTF dissolved in CH2Cl2 was quickly added by syringe. The formation of the hydroperoxo species was followed by the change in the absorbance at 395 nm. The 3 value of [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4) was determined to be 1.0 × 104 M−1 cm−1 measured in acetone at −80 °C.

Low Temperature Experiments Concerning the reaction of Mixed-valence [CuIICuI(LO)]2+ (D2) with O2

Under an argon atmosphere within a glove box, D1 (1.0 × 10−4 M) was mixed with Fc* (1.0 × 10−4 M) and TFA (1.0 × 10−3 M) in 3 mL O2-free acetone giving an orange solution. The cuvette was fully sealed with septum and quickly removed from the glove box and cooled down to −80 °C. O2 gas was then gently bubbled through the solution using a needle. The formation of the hydroperoxo species was followed by the change in the absorbance at 395 nm.

DFT Calculations

Density-functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed on a 32CPU workstation (PQS, Quantum Cube). Geometry optimizations were carried out using the Becke3LYP functional and lanl2dz basis set as implemented in the Gaussian 09 program Revision A.02.42 Graphical outputs of the computational results were generated with the Gauss View software program (ver. 3.09) developed by Semichem, Inc.43

Results and Discussion

Mechanism of D1-Catalyzed Two-Electron Reduction of O2 with Fc* to H2O2

For the sake of clarifying and a better understanding of this study, we prefer to present the mechanism of [CuII2(LO)(OH)]2+ (D1) catalyzed two-electron reduction of O2 with Fc* at the beginning, as shown in Scheme 3. What follows is our presentation of how the observations and data lead to this catalytic mechanism.

Scheme 3.

Reaction sequence deduced for the catalytic two-electron two-proton reduction of O2 to H2O2. The initial catalyst is [CuII2(LO)(OH)](SbF6)2 (D1) and the reaction is carried out in acetone solution using decamethylferrocene (Fc*) as reductant and trifluoroacetic acid (HOTF) as proton source. See text for further details, including the “short-circuit” path from D2 to D.

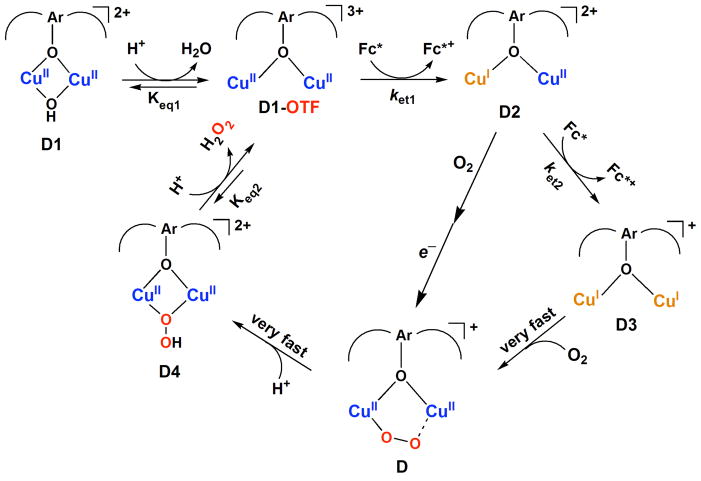

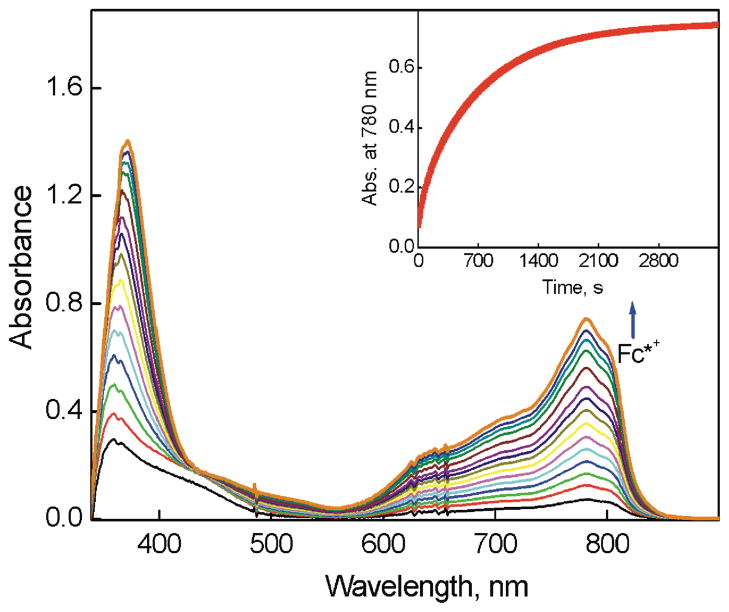

No oxidation of Fc* by O2 occurred in the absence and presence of [CuII2(LO)(OH)]2+ (D1) in acetone (Figure S2 in SI). However, when trifluoroacetic acid (HOTF) was added to the Fc*–O2–D1 system at 223 K, efficient oxidation of Fc* by O2 occurred to yield Fc*+ as indicated by an increase in the absorbance at 780 nm due to Fc*+ (Figure 1). When more than two equiv of Fc* relative to O2 (i.e., limiting [O2]) were employed,39 still only two equiv Fc*+ (λmax = 780 nm) were formed, even in the presence of excess HOTF (Figure S3 in SI). The stoichiometry of the catalytic oxidation of Fc* by O2 is given by eq 1 (Introduction). The formation of H2O2 was confirmed by the iodometric titration (Figure S4 in SI). The amount of I3− produced (λmax = 360 nm) was the same as that produced by the reaction of the stoichiometric amount of H2O2 with I− (Figure S5 in SI). Thus, selective two-electron reduction of O2 with Fc* occurred in the presence of excess HOTF and a catalytic amount of D1 in acetone at 223 K. When the temperature was raised to 298 K, the yield of H2O2 decreased to 55% because of competition with the direct reduction of H2O2 by Fc* (Figure S6 in SI). Thus, the kinetic analyses were performed at 223 K (vide infra).

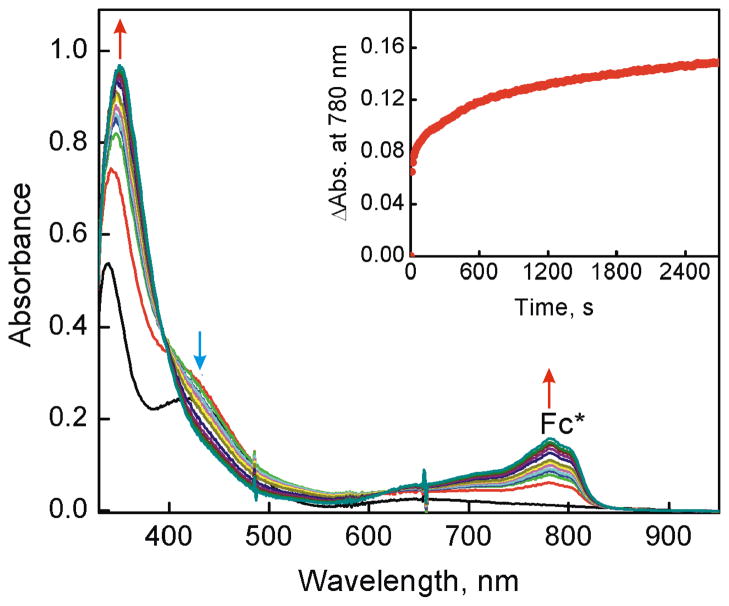

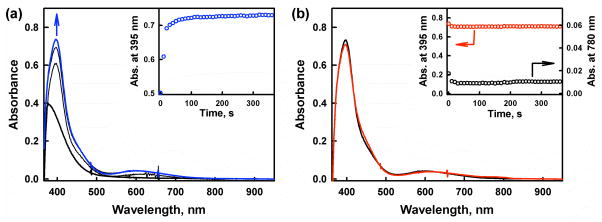

Figure 1.

UV-vis spectral changes observed in the two-electron reduction of O2 catalyzed by [CuII2(LO)(OH)] (D1) (0.040 mM) with Fc* (1.0 mM) in the presence of HOTF (3.0 mM) in O2-saturated acetone ([O2] = 11.0 mM) at 223 K. The Inset shows the time profile of the absorbance at 780 nm due to Fc*+.

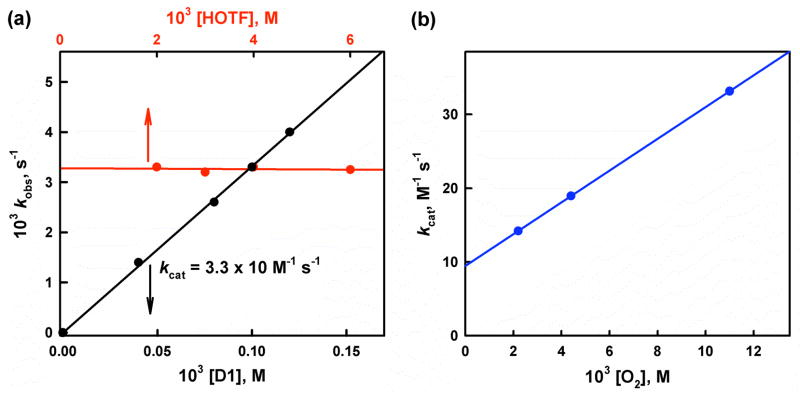

The rate of formation of Fc*+ (inset of Figure 1) obeyed first-order kinetics (Figure S7 in SI). The observed first-order rate constant increased linearly with increasing concentration of the catalyst (D1) as shown in Figure 2a. The dependence of kobs on concentration of HOTF was also examined and the results are shown in Figure 2b, where the kobs value remains the same with increasing concentration of HOTF. The dependence of kobs on concentration of O2 is shown in Figure 2c, where the kobs value increases linearly with increasing concentration of O2 and a clear intercept is recognized (Figure S8 in SI). Thus, the rate of formation of Fc*+ is given by eq 2,

Figure 2.

(a) Plot of the pseudo-first-order rate constants (kobs) vs concentrations of D1 (black line) to determine second-order rate constant (kcat) for the two-electron reduction of O2 catalyzed by D1 with Fc* (1.0 mM) in the presence of TFA (3.0 mM) in O2-saturated acetone ([O2] = 11.0 mM) at 223 K. Red line shows plot of kobs vs concentrations of TFA in the two-electron reduction of O2 catalyzed by D1 (0.10 mM) with Fc* (1.0 mM) in the presence of TFA in O2-saturated acetone ([O2] = 11.0 mM) at 223 K. (b) Plot of kcat vs concentrations of O2 in the two-electron reduction of O2 catalyzed by D1 (0.10 mM) with Fc* (1.0 mM) in the presence of TFA (3.0 mM) in acetone at 223 K.

| (2) |

| (3) |

where kcat is the second-order catalytic rate constant, k1 corresponds to the second-order rate constant, which is independent of concentration of O2, and k2 corresponds to the rate constant which is dependent of concentration of O2. In the next section, each step in the catalytic cycle in Scheme 3 is examined in detail to reconcile the kinetic formulation given by eqs 2 and 3.

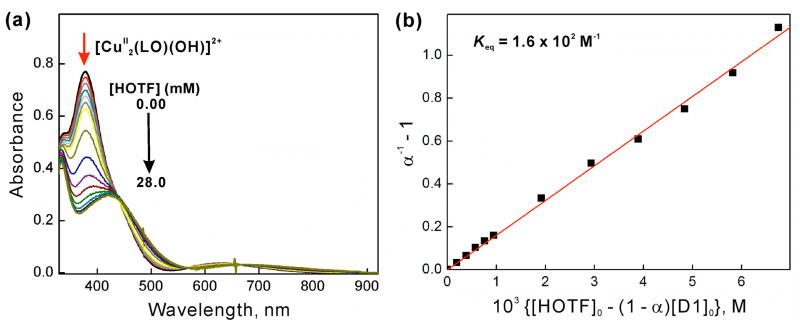

Protonation of [CuII2(LO)(OH)](SbF6)2 (D1)

Because no oxidation of Fc* by O2 occurred in the presence of D1 without added acid, a spectral titration of D1 with HOTF was carried out (Figure 3a). The result is that the absorption band at 378 nm due to [CuII2(LO)(OH)]2+ is red-shifted to 420 nm; a clean isosbestic point is observed at 430 nm. This spectral change is well analyzed by assuming formation of the protonated complex [CuII2(LO)(OTF)]2+ (D1-OTF); confirming evidence comes from a separate examination of the 1:1 reaction of HOTF with authentic D1.44 The protonation constant (K) of D1 to produce D1-OTF is determined by eq 4, where [D1]0 = [D1] + [D1 − HOTF], [D1]0 and [HOTF]0 are

Figure 3.

(a) UV-visible spectral changes of [CuII2(LO)(OH)] (D1) (0.20 mM) in the presence of HOTF (0.0 – 28.0 mM) in acetone at 298 K. (b) Plot of α−1 − 1 vs {[HOTF]0 − (1 − α)[D1]0} to determine the equilibrium constants (Keq) in the protonation of D1 upon addition of TFA (0.0 – 28.0 mM) into the solution of D1 (0.20 mM) in acetone at 298 K.

| (4) |

the initial concentrations of D1 and HOTF. Eq 4 is easily converted to eq 5, where α =

| (5) |

[D1]/[D1]0 = ΔA/ΔA0 (ΔA is the absorbance change at 378 nm due to D1 and ΔA0 corresponds to the absorbance change when all D1 molecules are converted to D1-OTF). A linear correlation between α−1 − 1 vs [HOTF]0 − (1 − α)[D1]0 shown in Figure 3b confirmed the validity of the assumption of the formation of CuII2(LO)(OTF))2+ (D1-OTF). Then, the K value is determined from the slope of a linear plot of α−1 − 1 vs [HOTF]0 − (1 − 3)[D1]0 (Figure 3b) to be 1.6 × 102 M−1. The temperature dependence of K was examined (Figure S9 in SI) and the van’t Hoff plot (Figure S10 in SI) afforded ΔH = −3.6 kcal mol−1 and ΔS = 2.1 cal K−1 mol−1.

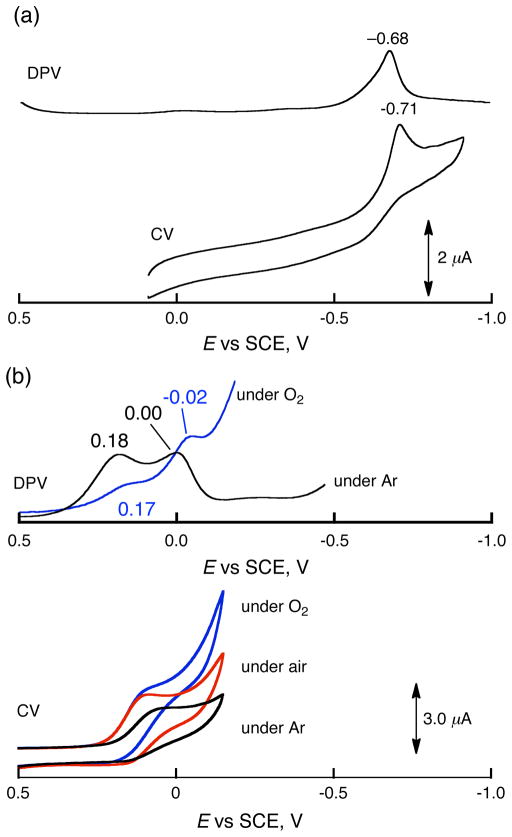

The binuclear Cu(II) complex [CuII2(LO)(OH)] (D1) is EPR silent because of antiferromagnetic coupling of the two Cu(II) ions. The protonated complex D1-OTF was also EPR silent (Figure S11 in SI). This indicates that two Cu(II) ions still maintain an electronic/magnetic interaction after the protonation of D1. Because the catalytic reduction of O2 by Fc* with D1 was made possible only by the presence of TFA, the effect of protonation of D1 by TFA on the one-electron reduction of D1 was examined by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and difference pulse voltammetry (DPV) measurements. Figure 4a shows a CV of D1 in acetone at 233 K. The irreversible cathodic peak current was observed at −0.71V vs SCE at a sweep rate of 0.10 V s−1 while the DPV exhibits the cathodic peak at −0.68 V vs SCE. The cathodic peak is much more negative as compared to the one-electron oxidation potential of Fc* (Eox = −0.08 V vs SCE).45–47,53,54 This is the reason why no electron transfer from Fc* to D1 ensues, thus precluding copper(I) formation, O2-reaction and Fc* oxidation.

Figure 4.

(a) Cyclic voltammograms and differential pulse voltammograms (DPV) of D1 (2.0 mM) in the absence of HOTF in deaerated acetone at 233 K. (b) CV and DPV of D1 (2.0 mM) in the presence of HOTF (50 mM) in deaerated (black), air-saturated (red) and O2-saturated (blue) acetone at 233 K. TBAPF6 (0.20 M) was used as an electrolyte.

In the presence of HOTF, however, the DPV peak is shifted to a positive direction as shown in Figure 4b, where a first and also a second one-electron reduction peak for [CuII2(LO)(OTF)]2+ (D1-OTF) are observed at 0.18 and 0.00 V vs SCE, respectively. This implied that a mixed-valence complex [CuIICuI(LO)]2+ (D2) may (and does) form (vide infra). In the presence of O2, a catalytic current for the reduction of O2 is observed at −0.02 V, which corresponds to the second one-electron reduction of D1-OTF (Scheme 3) and the catalytic current increases with increasing concentration of O2 (Figure 4b).

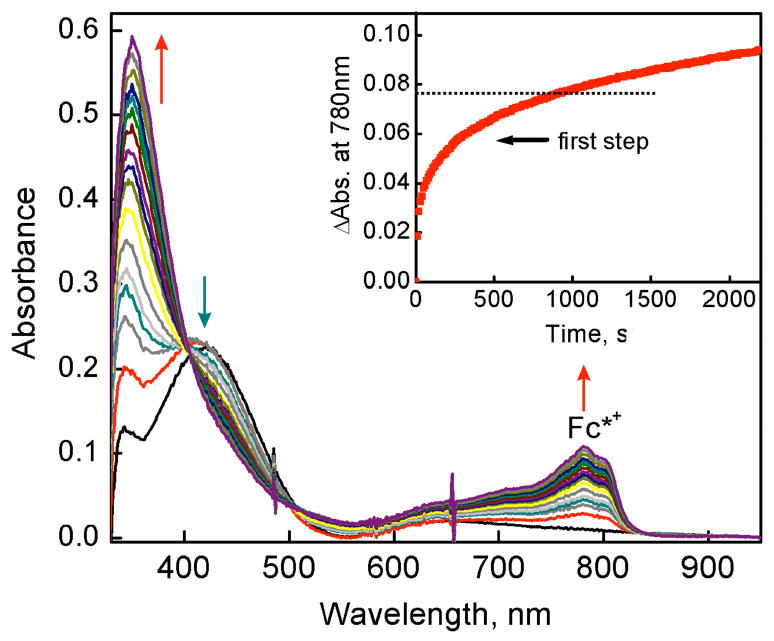

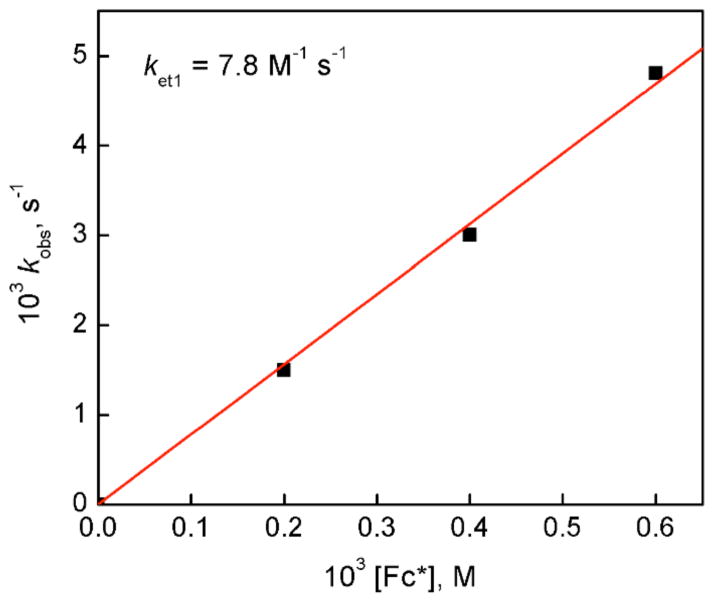

Two-Step Electron Transfer from Fc* to CuII2(LO)(OTf)]2+ (D1-OTF)

As said, the Eox value of Fc* is more negative than the first and second one-electron potentials of D1-OTF, making electron transfer from Fc* to D1-OTF thermodynamically feasible. Thus, we examined the dynamics of electron transfer from Fc* to D1-OTF. In fact, electron transfer from Fc* to D1 in the presence of HOTF occurs by a two step process, this as not being unexpected based on the observation that two one-electron reduction peaks are observed, Figure 4b. Figure 5 shows the UV-vis changes corresponding to the first step in the presence of 2.0 mM HOTF at 203 K. At this temperature most D1 molecules are converted to D1-OTF with 2.0 mM HOTF. The amount of Fc*+ produced in the first electron transfer from Fc* to D1-OTF is the same as the concentration of D1 (0.10 mM). The rate of formation of Fc*+ obeyed pseudo-first-order kinetics at the initial stage of the reaction in the presence of HOTF (3.0 mM) in acetone at 203 K (Figure S12 in SI). The observed pseudo-first-order rate constant (kobs) increases linearly with increasing the concentration of Fc* (Figure 6). The second-order rate constant (ket1) of electron transfer from Fc* to D1-OTF was determined to be 7.8 M−1 s−1 from the slope of a linear plot of kobs vs [Fc*] at 203 K.

Figure 5.

UV-vis spectral changes observed in the electron transfer from Fc* (0.40 mM) to [CuII2(LO)(OH)] (D1) (0.10 mM) in the presence of HOTF (2.0 mM) at 203 K. The Inset shows the time profile of the absorbance at 780 nm due to Fc*+, showing that 1 equiv Fc*+ is formed in the first step, i.e., first phase. Note: the nonzero absorbance at 780 nm before the mixing of D1 and Fc* is due to d-d transition of D1 complex, causing a large increase when the initial spectrum was recorded. This absorbance was subtracted from the total absorbance to give the absorbance due to Fc*+ to determine the rate constant.

Figure 6.

Plot of the pseudo-first-order rate constants (kobs) vs concentrations of Fc* in the first electron transfer from Fc* to [CuII2(LO)(OH)] (D1) (0.10 mM) to determine the ket1 value in the presence of HOTF (2.0 mM) in acetone at 203 K.

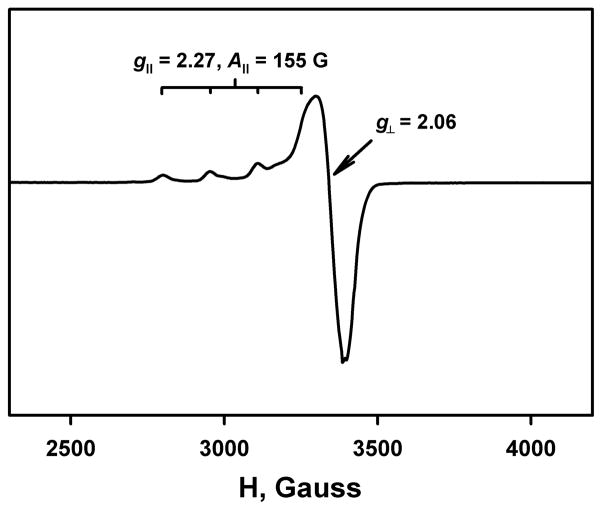

Figure 7 shows UV-vis monitoring of the second step of electron transfer from Fc* to D1-OTF, which corresponds to electron transfer from Fc* to the mixed-valence complex, [CuIICuI(LO)]2+ (D2). This could be separately generated by the one-electron reduction of D1 with one equivalent of Fc* in the presence of excess HOTF. EPR spectroscopic measurements confirmed the generation of D2, as this new species only exhibits signals due to the one Cu(II) moiety at g| = 2.27 and g⊥ = 2.06 (Figure 8), indicating that there is no delocalization of an electron between the Cu(I) and Cu(II) ions. A conproportionation reaction of a derived mixed-valence complex can be ruled out, since neither product of such a reaction, a dicopper(I) and phenolate (LO)-bridged dicopper(II) complex would be a simple copper(II) paramagnet. We note that with an unsymmetrical binucleating ligand very similar to LO, L’O, we previously also demonstrated the existence of a mixed-valence dicopper species [CuIICuI(L’O)]2+ possessing very similar EPR spectroscopic characteristics as observed here.48

Figure 7.

UV-vis spectral changes observed in the electron transfer from Fc* (1.2 mM) to [CuIICuI(LO)]2+ (D2) (0.10 mM), formed as described in the text, in the presence of HOTF (2.0 mM) at 213 K. The Inset shows the time profile of the absorbance at 780 nm due to Fc*+. Note: the nonzero absorbance at 780 nm before the mixing of D2 and Fc* is due to a d-d transition of this complex and this causes a large increase in recording of the first spectrum. For practical reasons this absorbance is subtracted from the total absorbance to give the absorbance due to Fc*+ to calculate the rate constant.

Figure 8.

EPR spectrum of [CuIICuI(LO)]2+ (D2) (1.0 mM) recorded in acetone at 5 K. D2 was generated in the reaction of D1 (1.0 mM) and Fc* (1.0 mM) in the presence of HOTF (5.0 mM) in acetone at 298 K. The experimental parameters: microwave frequency = 9.6483 GHz, microwave power = 1.0 mW, and modulation frequency = 100 kHz.

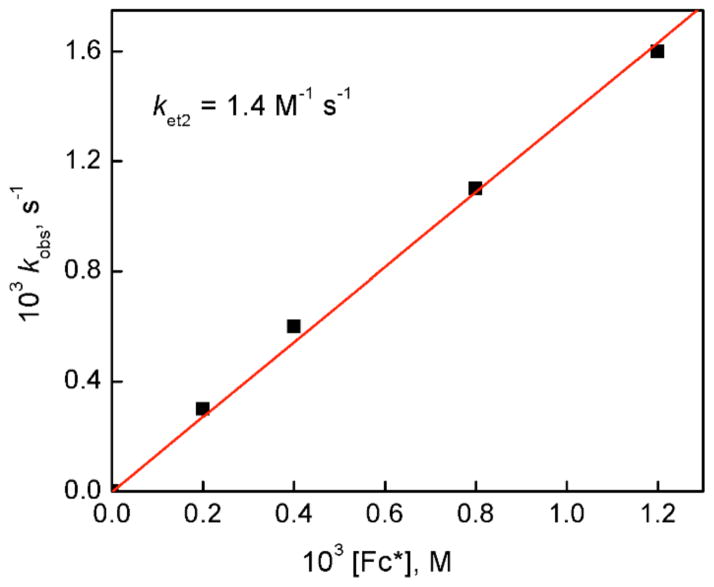

The kinetics of formation of Fc*+ in the second step electron transfer from Fc* to CuII2(LO)(OTf)]2+ (D1-OTF) in the presence of HOTF (3.0 mM) in acetone at 213 K (Figure 7) also obeyed pseudo-first-order kinetics (Figure S13 in SI) and the observed pseudo-first-order rate constant (kobs) also increases linearly with increasing concentration of Fc* (Figure 9). The second-order rate constant for electron transfer from Fc* to D1-OTF was determined from the slope of a linear plot of kobs vs [Fc*] to be 1.4 M−1 s−1 at 213 K. At this temperature the first step electron transfer was too fast to determine the ket1 value. When the temperature is raised to 223 K, the ket2 value increased to 5.4 M−1 s−1. It is important to note that the ket2 value determined from the second step electron transfer from Fc* to D1 in the presence of HOTF (2.0 mM) is one-half of the k1 value (11 M−1 s−1) obtained as an intercept in Figure 2b. This clearly indicates that the second step electron transfer from Fc* to D1 in the presence of HOTF is the rate-determining step in the catalytic cycle in Scheme 3, because once one equiv of Fc*+ is formed by electron transfer from Fc* to D2, another equiv of Fc*+ is rapidly formed by the first step electron transfer from Fc* to D1-OTF. In such a case, the rate of formation of Fc*+ is derived from Scheme 3 as given by eq 6. By comparing eq 6 with the

Figure 9.

Plot of the pseudo-first-order rate constants (kobs) vs concentrations of Fc* in the second electron transfer from Fc* to [CuIICuI(LO)]2+ (D2) (0.10 mM) to determine the ket2 value in the presence of HOTF (2.0 mM) in acetone at 213 K.

| (6) |

experimental results (eqs 1 and 2), k1 in kcat (eq 2) corresponds to 2ket2, i.e., ket2 = (1/2)k1(intercept).

The temperature dependence of ket2 was examined and the Eyring plot (Figure S14 in SI) afforded the activation enthalpy (ΔH≠ = 11.2 ± 0.2 kcal mol−1) and activation entropy (ΔS≠ = 2 ± 2 cal K−1 mol−1). An activation entropy close to zero was previously reported for electron transfer from ferrocene derivatives to Cu(II) complexes.47

Cu(II)-Peroxo and –Hydroperoxo Intermediates in the Stoichiometric Two-Electron Reduction of O2 by Fc* in the Presence of HOTF

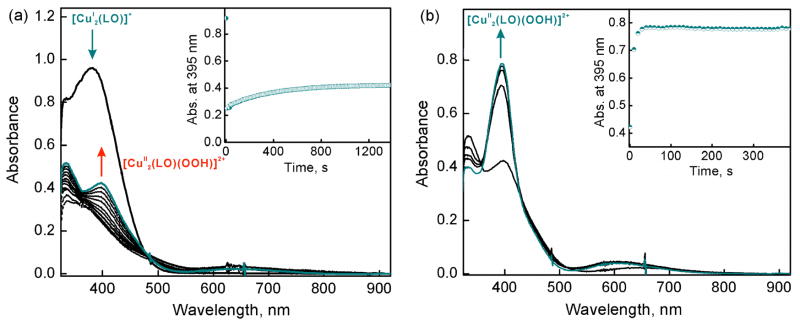

The Cu(II)-oxygen intermediates likely involved in the catalytic two-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* in Scheme 3 were examined by following the reaction an isolated sample of dicopper(I) complex, [CuI2(LO)]+ (D3), with O2 at 193 K. When O2 was introduced to an acetone solution of D3, the peroxo complex [CuII2(LO)(OO)]+ (D) which should form very rapidly (see Introduction) is however slowly converted to the hydroperoxo complex, [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4) as indicated by an increase in the absorption band at 395 nm. This can be explained by the occurrence of the reaction of [CuII2(LO)(OO)]+ (D) with residual water in acetone (Figure 10a). Instead, when one equiv of HOTF is added to the solution containing D the hydroperoxo complex D4 forms very rapidly (Figure 10b), as expected.29

Figure 10.

UV-vis spectral changes and time profiles of (a) [CuI2(LO)]+ (D3) (0.070 mM) after O2 introduction demonstrating the generation of [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4) at 395 nm and (b) D3 (0.070 mM) after O2 introduction and addition of 1 equiv HOTF (0.070 mM) in acetone at 193 K.

When one equiv of HOTF was added before the reaction of [CuI2(LO)]+ (D3) with O2, an immediate transformation occurs to give only hydroperoxo complex [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4) (Figure 11a). This indicates that the protonation of the peroxo complex with HOTF is much faster than the formation of the peroxo complex itself. In contrast with the case of μ- η2: η2-peroxo dicopper(II) and bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) complexes, which were readily reduced by Fc*,29 no electron transfer from Fc* to the hydroperoxo complex [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4) occurred as shown in Figure 11b, where the absorption spectrum due to D4 was not changed by the addition of Fc*. This is the reason why the selective two-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* occurs, i.e., the hydroperoxo-dicopper(II) complex D4 is not susceptible to reduction, thus with catalyst and HOTF, H2O2 is produced.

Figure 11.

(a) Full formation of the [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4) in an acetone solution containing [CuI2(LO)]+ (D3) (0.070 mM) and HOTF (0.070 mM) after O2 introduction at 193 K. Inset shows the absorbance change at 395 nm due to the generated hydroperoxo species. (b) Addition of excess Fc* (0.28 mM) (red spectrum) to the hydroperoxo species generated (black spectrum) in acetone at 193 K.

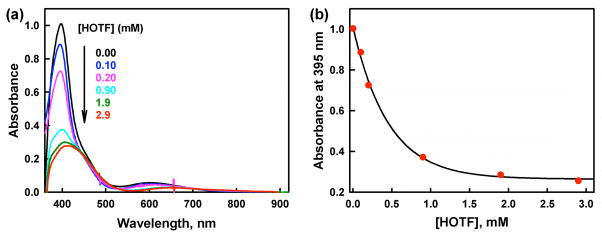

When HOTF was further added to an acetone solution of [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4), the absorption band due to D4 disappeared as the concentration of HOTF increased (Figure 12a) indicating that this reaction directly produces [CuII2(LO)(OTF)]2+ (D1-OTF) and hydrogen peroxide. The amount of 10 equiv of HOTF is enough for a quantitative reaction to take place (Figure 12b).

Figure 12.

(a) UV-visible spectral changes of [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4) (0.10 mM) in the presence of HOTF (0.10 – 3.0 mM) in acetone at 193 K. (b) Absorbance changes at 395 nm as a function of HOTF concentration.

The Reactivity of Mixed-Valence [CuIICuI(LO)]2+ (D2) with O2 in the Presence of HOTF

The electron-transfer reduction of [CuII2(LO)(OTF)]2+ (D1-OTF) with Fc* with under single turnover conditions without O2 clearly shows that the two-electron reduction takes place in two successive steps in which the second step is slower and this is the rate-determining step in the catalytic cycle in Scheme 3 as described above (see also Figures 5 and 7). Under the catalytic conditions, however, the observed catalytic rate constant (kcat) in the presence of O2 is larger than twice the rate constant of the second step electron transfer, kcat > 2ket2. This suggests that the initial electron-transfer reduction of D1-OTF may be followed by the reaction with O2 in addition to a second-step electron transfer. This possibility was tested by directly examining the reactivity of the mixed-valence [CuIICuI(LO)]2+ (D2) species with O2 and in the presence of HOTF.

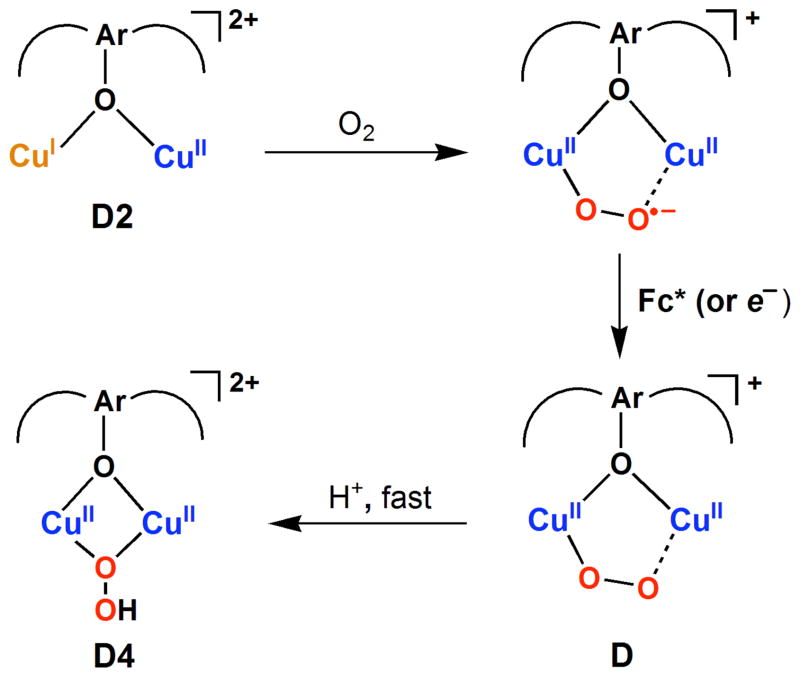

When O2 is introduced to an acetone solution of [CuIICuI(LO)]2+ (D2) at 193 K, the hydroperoxo complex [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4) is immediately formed (Figure 13) and is then protonated in the presence of excess acid to give off hydrogen peroxide (see the inset of Figure 13). The amount of D4 produced is about the one-half of the amount of D2 judging from a comparison of the results in Figure 13 with those in Figure 11. This indicates that the reaction of D2 with O2 affords an O2-adduct of D2, a putative superoxo-dicopper(II) species [CuII2(LO)(O2•−)]2+ (CuII2(O2•−)), which is reduced by a second molecule of [CuIICuI(LO)]2+ (D2) and then protonated to give ~ 0.5 equiv of D4. Under catalytic conditions, however, [CuII2(LO)(O2•−)]2+ may be reduced by Fc* that is present to produce one equiv of D4. Thus, the full catalytic cycle may not actually proceed via dicopper(I) complex [CuI2(LO)]+ (D3) or peroxodicopper(II) complex [CuII2(LO)(OO)]+ (D), but is “short-circuited” as shown in Scheme 4 (and this is also included in Scheme 3).

Figure 13.

(a) UV-visible spectral changes resulted from introduction of O2 at 193 K into an acetone solution of [CuIICuI(LO)]2+ (D2) (green spectrum) produced from room temperature mixing of [CuII2(LO)(OH)] (D1) (0.10 mM) and Fc* (0.10 mM) in the presence of HOTF (1.0 mM). The Inset shows the time profile of the absorbance at 395 nm due to the [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4) generated (red spectrum).

Scheme 4.

Protonation vs Electron-Transfer Reduction of [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4)

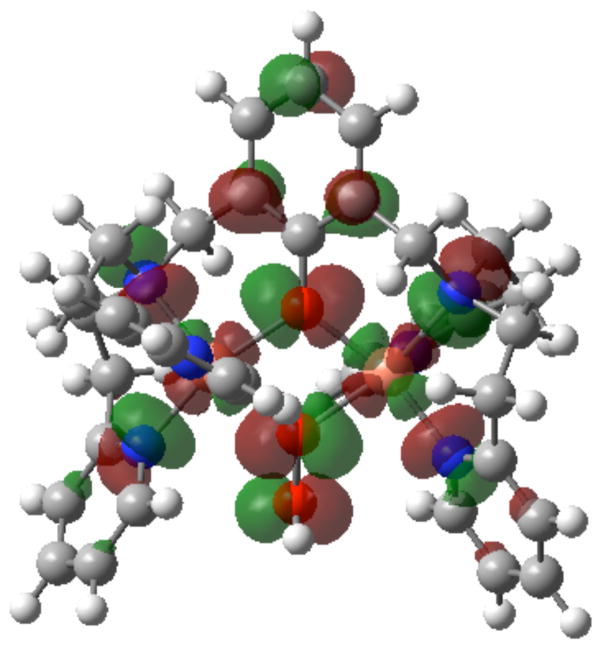

Concerning the fact that D4 undergoes protonation releasing hydrogen peroxide, rather than reductive cleavage by Fc*, as do complexes with an dioxygen derived “trans”-μ-1,2-peroxo dicopper(II) (A), μ- η2: η2-peroxo dicopper(II) (B) or bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) (C) structure (see Introduction) complexes, one can consider a number of points. For one thing, see the DFT-optimized structure of D4 shown in Figure 14 together with the LUMO orbital (for the calculation, see the Experimental Section). The optimized structure does possess a μ-1,1-OOH ligand as previously proposed based on physical-spectroscopic methods, and the two calculated Cu-Ohydroperoxo distances in [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4) are nearly the same (2.044 and 2.046 Å). Because the LUMO orbital is delocalized to not only the metal but also to the ligands, the one-electron reduction of D4 may not (and does not) lead to O-O bond cleavage for the further reduction to water. Instead, [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4) releases H2O2 upon protonation.

Figure 14.

Optimized structure with LUMO orbital of [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4) calculated by DFT B3LYP/lanl2dz basis set.

Another point is that it has been shown that in copper complexes the O–O bond becomes stronger upon protonation (−OOH) or alkylation (−OOR).49 Thus, a relatively stronger O–O bond would in the presence of protons undergo copper-O cleavage giving H2O2 rather than O–O cleavage eventually leading to water (and the 4e−/4H+ reduction of O2). The bonding within a μ- η2: η2-peroxo dicopper(II) Cu2O2 core is well known to produce very weak O–O bonds, possessing ν(O–O) = 710–760 cm−1 (see Scheme 2). Thus, such complexes would be more susceptible to O–O reductive cleavage by Fc* and protons, just as we have recently reported for the case of [CuII2(N3)(μ-η2:η2-O22−)]2+ (see Introduction).17b,50 This is further supported by calculations on the LUMO of [CuII2(N3)(μ-η2:η2-O22−)]2+ (Figure 15a) which show it to be mainly localized at the anti-bonding O-O bond orbitals. And also [{(BzPY1)CuIII}2(μ-O2−)2]2+, formed from reduction of [CuII(BzPY1)(EtOH)](ClO4)2 (C1) and which promote bis-μ-oxo-dicopper(III) formation, as in this case, would likely promote 4e−/4H+ reduction of O2. Note that for [{(BzPY1)CuIII}2(μ-O2−)2]2+, the LUMO is mainly localized at the cleaved oxygen atom orbitals (Figure 15b).

Figure 15.

Optimized structures with LUMO of (a) [CuII2(N3)(O2)]2+ calculated and (b) [(BzPY1)CuIII(BzPY1)(O)2CuIII(BzPY1)]2+ by DFT B3LYP/Lanl2dz.

What is perhaps a puzzle at this point, is that the (TMPA)-copper system, which provides for chemistry leading to [{(TMPA)CuII}2(μ-1,2-O22−)]2+ (A1) also gives rise to O–O reductive cleavage chemistry (vide supra).17a Yet, the O–O bond in this complex is strong, ν(O–O) ~ 830 cm−1.51 One may conjecture that the peroxo group in A1 is well protected relative to the −OOH group in [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]2+ (D4), and that protonation of the latter is extremely fast, while for A1, outer-sphere proton-coupled electron-transfer reduction by Fc* easily proceeds. Certainly other factors may come into play, and a more rigorous experimental and theoretical understanding concerning preference for protonation or reduction surely will come about as more examples of both 4e−/4H+ O2-reduction to water and 2e−/2H+ reduction of O2 to hydrogen peroxide are found and investigated in detail.

Summary and Conclusion

A binuclear copper(II) complex ([CuII2(LO)(OH)]2+) acts as an efficient catalyst for the selective two-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* with HOTF in acetone as shown in Scheme 3. The protonation of [CuII2(LO)(OH)]2+ with HOTF results in formation of [CuII2(LO)(OTF)]2+, which can be reduced by Fc* via two step electron-transfer reactions to produce [CuI2(LO)]+ via the mixed valance complex ([CuIICuI(LO)]2+. Binuclear Cu(I) complex [CuI2(LO)]+ reacts with O2 rapidly in the presence of HOTF to produce the hydroperoxo complex ([CuII2(LO)(OOH)]+) via protonation of an intermediate peroxo complex ([CuII2(LO)(OO)]). Further protonation of [CuII2(LO)(OOH)]+ with HOTF produces H2O2, accompanied by regeneration of [CuII2(LO)(OTF)]2+. The rate-determining step in the predominant catalytic cycle given in Scheme 3 is the second step electron transfer, thus Fc* reduction of a mixed-valent complex [CuIICuI(LO)]2+ where this is coupled with O2-binding to produce peroxo complex [CuII2(LO)(OO)]+. However, another reaction pathway consists of direct O2-reaction with [CuIICuI(LO)]2+, followed by electron-transfer reduction of an O2-adduct that must be formed, to give peroxo complex [CuII2(LO)(OO)]+ (Scheme 4).

This is the first selective two-electron reduction of O2 by a one-electron reductant with a copper complex acting as a catalyst. Future modifications of the supporting ligand may improve the catalytic activity for the selective two-electron reduction of O2 to H2O2, the latter being a promising candidate as a renewable and clean energy source.30–32

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research at OU was supported by Grant-in-Aid (No. 19205019 to S.F.) and Global COE program, “the Global Education and Research Center for Bio-Environmental Chemistry” from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (to S.F.) and the research at EWU was supported by NRF/MEST of Korea through CRI (to W.N.), GRL (2010-00353) (to W.N.), 2011 KRICT OASIS project (to W.N.), and WCU (R31-2008-000-10010-0) (to W.N., S.F. and K.D.K.). K.D.K. also acknowledges support from the USA National Institutes of Health grant, GM28962.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Figures S1–S14. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Contributor Information

Shunichi Fukuzumi, Email: fukuzumi@chem.eng.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Wonwoo Nam, Email: wwnam@ewha.ac.kr.

Kenneth D. Karlin, Email: karlin@jhu.edu.

References

- 1.(a) Solomon EI, Ginsbach JW, Heppner DE, Kieber-Emmons MT, Kjaergaard CH, Smeets PJ, Tian L, Woertink JS. Faraday Discuss. 2011;148:11–39. doi: 10.1039/c005500j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Solomon EI, Sundaram UM, Machonkin TE. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2563–2605. doi: 10.1021/cr950046o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Solomon EI, Chen P, Metz M, Lee SK, Palmer AE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:4570–4590. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4570::aid-anie4570>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Karlin KD, Tyeklár Z, editors. Bioinorganic Chemistry of Copper. Chapman & Hall; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]; (e) Karlin KD, Zuberbühler AD. Formation, Structure and Reactivity of Copper Dioxygen Complexes. In: Reedijk J, Bouwman E, editors. Bioinorganic Catalysis. 2. Marcel Dekker, Inc; New York: 1999. pp. 469–534. Revised and Expanded. [Google Scholar]; (f) Quant Hatcher L, Karlin KD. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:669–683. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0578-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Lee Y, Karlin KD. Highlights of Copper Protein Active-Site Structure/Reactivity and Synthetic Model Studies. In: Metzler-Nolte N, Kraatz H-B, editors. Concepts and Models in Bioinorganic Chemistry. Wiley-VCH; New York: 2006. pp. 363–395. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Holm RH, Kennepohl P, Solomon EI. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2239–2314. doi: 10.1021/cr9500390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Karlin KD. Science. 1993;261:701–708. doi: 10.1126/science.7688141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Metzler-Nolte N, Kraatz H-B. Concepts and Models in Bioinorganic Chemistry. Wiley-VCH; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Mirica LM, Ottenwaelder X, Stack TDP. Chem Rev. 2004;104:1013–1045. doi: 10.1021/cr020632z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lewis EA, Tolman WB. Chem Rev. 2004;104:1047–1076. doi: 10.1021/cr020633r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Itoh S, Fukuzumi S. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:592–600. doi: 10.1021/ar6000395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Itoh S. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Klinman JP. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2541–2561. doi: 10.1021/cr950047g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Klinman JP. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3013–3016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Prigge ST, Eipper B, Mains R, Amzel LM. Science. 2004;304:864–867. doi: 10.1126/science.1094583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chen P, Solomon EI. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2004;101:13105–13110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402114101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Balasubramanian R, Smith SM, Rawat S, Yatsunyk LA, Stemmler TL, Rosenzweig AC. Nature. 2010;465:115–119. doi: 10.1038/nature08992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Chan SI, Yu SSF. Accounts Chem Res. 2008;41:969–979. doi: 10.1021/ar700277n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humphreys KJ, Mirica LM, Wang Y, Klinman JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:4657–4663. doi: 10.1021/ja807963e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukherjee A, Smirnov VV, Lanci MP, Brown DE, Shepard EM, Dooley DM, Roth JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9459–9473. doi: 10.1021/ja801378f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGuirl MA, Dooley DM. Copper Proteins with Type 2 Sites. In: King RB, editor. Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry. 2. II. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; Chichester: 2005. pp. 1201–1225. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Solomon EI, Augustine AJ, Yoon J. Dalton Trans. 2008:3921–3932. doi: 10.1039/b800799c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Messerschmidt A. Adv Inorg Chem. 1993;40:121–185. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rodgers CJ, Blanford CF, Giddens SR, Skamnioti P, Armstrong FA, Gurr SJ. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kosman D. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2010;15:15–28. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0590-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Djoko KY, Chong LX, Wedd AG, Xiao Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2005–2015. doi: 10.1021/ja9091903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Ferguson-Miller S, Babcock GT. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2889–2907. doi: 10.1021/cr950051s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yoshikawa S, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Nakashima R, Yaono R, Yamashita E, Inoue N, Yao M, Jei-Fei M, Libeu CP, Mizushima T, Yamaguchi H, Tomizaki T, Tsukihara T. Science. 1998;280:1723–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Michel H, Behr J, Harrenga A, Kannt A. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1998;27:329–356. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Pereira MM, Sousa FL, VerÌssimo AF, Teixeira M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:929–934. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.05.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yoshikawa S, Muramoto K, Shinzawa-Itoh K. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:1279–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Collman JP, Devaraj NK, Decreau RA, Yang Y, Yan YL, Ebina W, Eberspacher TA, Chidsey CED. Science. 2007;315:1565–1568. doi: 10.1126/science.1135844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Collman JP, Decréau RA, Lin H, Hosseini A, Yang Y, Dey A, Eberspacher TA. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2009;106:7320–7323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902285106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Collman JP, Ghosh S, Dey A, Decréau RA, Yang Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5034–5035. doi: 10.1021/ja9001579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadish KM, Frémond L, Shen J, Chen P, Ohkubo K, Fukuzumi S, El Ojaimi M, Gros CP, Barbe J-M, Guilard R. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:2571–2582. doi: 10.1021/ic802092n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Hatay I, Su B, Li F, Méndez MA, Khoury T, Gros CP, Barbe JM, Ersoz M, Samec Z, Girault HH. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13453–13459. doi: 10.1021/ja904569p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Partovi-Nia R, Su B, Li F, Gros CP, Barbe JM, Samec Z, Girault HH. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:2335–2340. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hatay I, Su B, Méndez MA, Corminboeuf C, Khoury T, Gros CP, Bourdillon M, Meyer M, Barbe JM, Ersoz M, Zális S, Samec Z, Girault HH. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13733–13741. doi: 10.1021/ja103460p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Partovi-Nia R, Su B, Méndez MA, Habermeyer B, Gros CP, Barbe JM, Samec Z, Girault HH. ChemPhysChem. 2010;11:2979–2984. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Su B, Hatay I, Trojánek A, Samec Z, Khoury T, Gros CP, Barbe JM, Daina A, Carrupt PA, Girault HH. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2655–2662. doi: 10.1021/ja908488s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zagal JH, Griveau S, Silva JF, Nyokong T, Bedioui F. Coord Chem Rev. 2010;254:2755–2791. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halime Z, Kotani H, Li Y, Fukuzumi S, Karlin KD. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2011;108:13990–13994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104698108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cracknell JA, Vincent KA, Armstrong FA. Chem Rev. 2008;108:2439–2461. doi: 10.1021/cr0680639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Fukuzumi S, Kotani H, Lucas HR, Doi K, Suenobu T, Peterson RL, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6874–6875. doi: 10.1021/ja100538x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tahsini L, Kotani H, Lee YM, Cho J, Nam W, Karlin KD, Fukuzumi S. Chem-Eur J. 2012;18:1084–1093. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Thorum MS, Yadav J, Gewirth AA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:165–167. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Thorseth MA, Letko CS, Rauchfuss TB, Gewirth AA. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:6158–6162. doi: 10.1021/ic200386d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) McCrory CCL, Devadoss A, Ottenwaelder X, Lowe RD, Stack TDP, Chidsey CED. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:3696–3699. doi: 10.1021/ja106338h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Fukuzumi S, Mochizuki S, Tanaka T. Inorg Chem. 1989;28:2459–2465. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuzumi S, Mochizuki S, Tanaka T. Inorg Chem. 1990;29:653–659. [Google Scholar]; (c) Fukuzumi S, Mochizuki S, Tanaka T. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1989:391–392. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukuzumi S. Chem Lett. 2008;37:808–813. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kadish KM, Shen J, Fremond L, Chen P, El Ojaimi M, Chkounda M, Gros CP, Barbe JM, Ohkubo K, Fukuzumi S, Guilard R. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:6726–6737. doi: 10.1021/ic800458s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Fukuzumi S, Okamoto K, Gros CP, Guilard R. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10441–10449. doi: 10.1021/ja048403c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuzumi S, Okamoto K, Tokuda Y, Gros CP, Guilard R. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:17059–17066. doi: 10.1021/ja046422g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Rosenthal J, Nocera DG. Prog Inorg Chem. 2007;55:483–544. [Google Scholar]; (b) Rosenthal J, Nocera DG. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:543–553. doi: 10.1021/ar7000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tyeklár Z, Karlin KD. Acc Chem Res. 1989;22:241–248. [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Thyagarajan S, Murthy NN, Narducci Sarjeant AA, Karlin KD, Rokita SE. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7003–7008. doi: 10.1021/ja061014t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Karlin KD, Tyeklár Z, Farooq A, Haka MS, Ghosh P, Cruse RW, Gultneh Y, Hayes JC, Toscano PJ, Zubieta J. Inorg Chem. 1992;31:1436–1451. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lucas HR, Li L, Sarjeant AAN, Vance MA, Solomon EI, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3230–3245. doi: 10.1021/ja807081d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karlin KD, Gultneh Y, Hayes JC, Cruse RW, McKown JW, Hutchinson JP, Zubieta J. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:2121–2128. [Google Scholar]

- 28.(a) Karlin KD, Cruse RW, Gultneh Y, Hayes JC, Zubieta J. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:3372–3374. [Google Scholar]; (b) Karlin KD, Cruse RW, Gultneh Y, Farooq A, Hayes JC, Zubieta J. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:2668–2679. [Google Scholar]; (c) Pate JE, Cruse RW, Karlin KD, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:2624–2630. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karlin KD, Ghosh P, Cruse RW, Farooq A, Gultneh Y, Jacobson RR, Blackburn NJ, Strange RW, Zubieta J. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:6769–6780. [Google Scholar]

- 30.(a) Yamada Y, Fukunishi Y, Yamazaki S-i, Fukuzumi S. Chem Commun. 2010;46:7334–7336. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01797c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jing X, Cao DX, Liu Y, Wang GL, Yin JL, Wen Q, Gao YY. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 2011;658:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 31.For metal-hydrogen peroxide semi-fuel cells, see reference 32.

- 32.(a) Lei T, Tian YM, Wang GL, Yin JL, Gao YY, Wen Q, Cao DX. Fuel Cells. 2011;11:431–435. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hasvold O, Storkersen NJ, Forseth S, Lian T. J Power Sources. 2006;162:935–942. [Google Scholar]; (c) Patrissi CJ, Bessette RR, Kim YK, Schumacher CR. J Electrochem Soc. 2008;155:B558–B562. [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Disselkamp RS. Energ Fuel. 2008;22:2771–2774. [Google Scholar]; (b) Disselkamp RS. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2010;35:1049–1053. [Google Scholar]

- 34.(a) Galbács ZM, Csányi LJ. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1983:2353–2357. [Google Scholar]; (b) Latimer WM. The Oxidation States of the Elements and their Potentials in Aqueous Solutions. Prentice-Hall; New York: 1952. p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- 35.(a) Abrantes S, Amaral E, Costa AP, Shatalov AA, Duarte AP. Ind Crop Prod. 2007;25:288–293. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zeronian SH, Inglesby MK. Cellulose. 1995;2:265–272. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li L, Lee S, Lee HL, Youn HJ. Bioresources. 2011;6:721–736. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armarego WLF, Chai CLL. Purification of Laboratory Chemicals. 5. Butterworth-Heinemann; Amsterdam: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mann CK, Barnes KK. Electrochemical Reactions in Nonaqueous Systems. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 39.The O2 concentration in an O2-saturated acetone solution (11 mM) was determined by the spectroscopic titration for the photooxidation of 10-methyl-9.10-dihydroacridine by O2; see: Fukuzumi S, Ishikawa M, Tanaka T. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1989;2:1037.

- 40.Battino R. Oxygen and Ozone. Vol. 7 Pergamon Press; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 41.(a) Mair RD, Graupner AJ. Anal Chem. 1964;36:194. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuzumi S, Kuroda S, Tanaka T. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:3020–3027. [Google Scholar]

- 42.(a) Becke AD. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee CT, Yang WT, Parr RG. Physical Review B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Heher WJ, Radom K, Schleyer PvR, Pople JA. Ab Initio Molecular Orbital Theory. Wiley; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dennington R, II, Keith R, Millam J, Eppinnett K, Hovell WL, Gilliland R. Semichem, Inc. Shawnee Mission; KS: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Although the protonation equilibirum was well analyzed by assuming formation of a 1:1 complex between D1 and HOTF, whether H2O is still coordinated or not has yet to be clarified. However, ESI-MS analysis of such solutions which have λmax = 420 nm do show a pominent peak corresponding to the monocation {[CuII2(LO)(OTF)](OTF)}+

- 45.For Eox values of ferrocene derivatives in acetone, see the following reference:

- 46.(a) Lee YM, Kotani H, Suenobu T, Nam W, Fukuzumi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:434–435. doi: 10.1021/ja077994e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuzumi S, Kotani H, Prokop KA, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1859–1869. doi: 10.1021/ja108395g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fukuzumi S, Kotani H, Suenobu T, Hong S, Lee YM, Nam W. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:354–361. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Comba P, Fukuzumi S, Kotani H, Wunderlich S. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:2622–2625. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.The activation entropy for electron transfer becomes negative when the electron transfer occurs via an intermediate; see: Fukuzumi S, Endo Y, Imahori H. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10974–10975. doi: 10.1021/ja026089l.

- 48.Mahroof-Tahir M, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:7599–7601. [Google Scholar]

- 49.(a) Root DE, Mahroof-Tahir M, Karlin KD, Solomon EI. Inorg Chem. 1998;37:4838–4848. doi: 10.1021/ic980606c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen P, Fujisawa K, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:10177–10193. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pidcock E, Obias HV, Abe M, Liang HC, Karlin KD, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:1299–1308. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baldwin MJ, Ross PK, Pate JE, Tyeklár Z, Karlin KD, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:8671–8679. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.