Abstract

Highly functionalized cyclopentenones can be generated stereospecifically by a chemoselective copper(II)-mediated Nazarov/Wagner-Meerwein rearrangement sequence of divinyl ketones. A detailed investigation of this sequence is described including a study of substrate scope and limitations. After the initial 4π electrocyclization, this reaction proceeds via two different sequential [1,2]-shifts, with selectivity that depends upon either migratory ability or the steric bulkiness of the substituents at C1 and C5. This methodology allows the creation of vicinal stereogenic centers, including adjacent quaternary centers. This sequence can also be achieved by using a catalytic amount of copper(II) in combination with NaBAr4f, a weak Lewis acid. During the study of the scope of the reaction, a partial or complete E / Z isomerization of the enone moiety was observed in some cases prior to the cyclization, which resulted in a mixture of diastereomeric products. Use of a Cu(II)-bisoxazoline complex prevented the isomerization, allowing high diastereoselectivity to be obtained in all substrate types. In addition, the reaction sequence was studied by DFT computations at the UB3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level, which are consistent with the proposed sequences observed, including E / Z isomerizations and chemoselective Wagner-Meerwein shifts.

Introduction

Electrocyclizations are powerful pericyclic reactions that occur via simple orbital reorganization.1 They are one of the few methods available to create carbon-carbon bonds stereospecifically. Cationic electrocyclizations, such as the Nazarov (4π cationic) cyclization, are initiated by formation of an extended cationic π-system, which also reacts with conservation of orbital symmetry.2 In the past few years numerous examples of catalytic Nazarov cyclizations have been reported,3–11 and asymmetric induction in the Nazarov cyclization has been achieved using chiral auxiliaries,12 chiral Lewis acids13 or organocatalysts,14 but the substrate scope is narrow in each case. The Nazarov cyclization can also serve as a cationic initiation step, generating an oxyallyl cation intermediate that can be intercepted by a suitable trapping agent.15 This oxyallyl cation can also be the starting point for rearrangement sequences.16 In a general sense, these reactions fit within a larger class of cationic cascades that involve activation of a carbonyl or alkene functionality to generate "stabilized" carbocation intermediates, which can undergo a variety of subsequent transformations. Cation-initiated C-C bond-forming reactions have great synthetic potential, if their reactivity and selectivity can be controlled, especially in the area of terpene and steroid biosynthesis.17

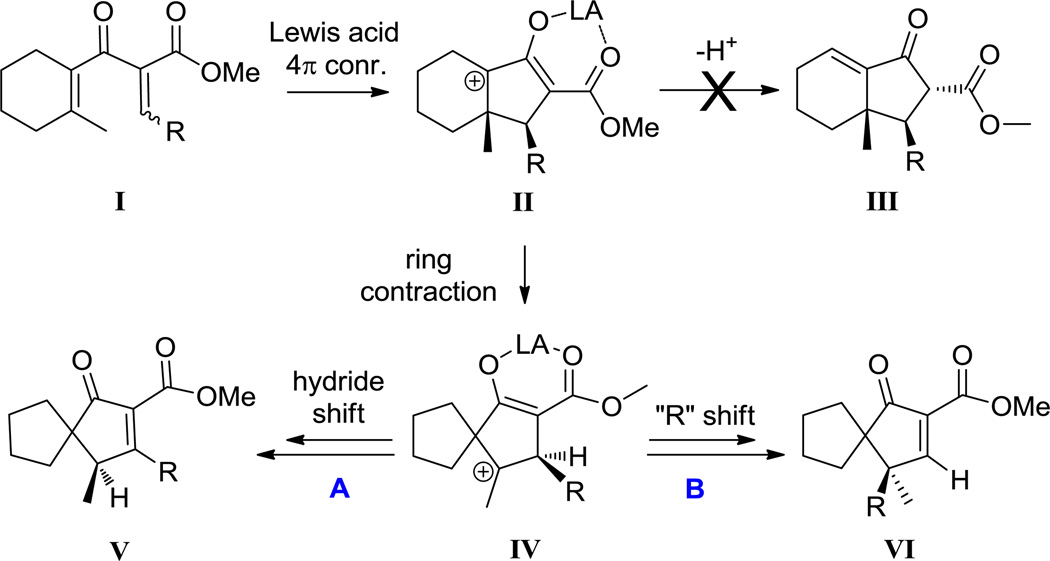

In our studies on the Nazarov cyclization, we found an interesting and unusual electrocyclization/rearrangement sequence that could efficiently compete with the traditional Nazarov cyclization when stoichiometric amounts of Ligand-Cu(SbF6)2 were employed.18 Experiments suggest that these reaction conditions suppress proton transfer, extending the lifetime of the oxyallyl cation and allowing rearrangement pathways to compete with elimination (Scheme 1). It is possible to achieve the stereospecific synthesis of unusual spirocyclic compounds with adjacent stereogenic centers, including adjacent quaternary centers. However, this initial study revealed the following limitations: (i) one full equivalent of Lewis acid promoter was required for rearrangement; (ii) the reaction scope was limited to cyclic substrates.

Scheme 1.

Spirocycle synthesis via Nazarov/ Wagner-Meerwein rearrangement sequence.

Recently, we have shown that this reaction does not require the use of a sophisticated ligand and can even be carried out with a catalytic amount of a copper (II) complex.19 Highly functionalized cyclopentenones can be prepared stereospecifically via conrotatory electrocyclization, with high chemoselectivity of subsequent Wagner-Meerwein shifts. In many cases, it is possible to install adjacent quaternary centers with complete diastereocontrol. The present article is devoted to the investigations conducted by our laboratory to evaluate the scope and the limitations of this copper(II)-mediated Nazarov cyclization/Wagner-Meerwein rearrangement sequence of acyclic substrates To gain insight into the mechanism of the title reaction, the key steps have also been analyzed by means of DFT calculations.

Results and Discussion

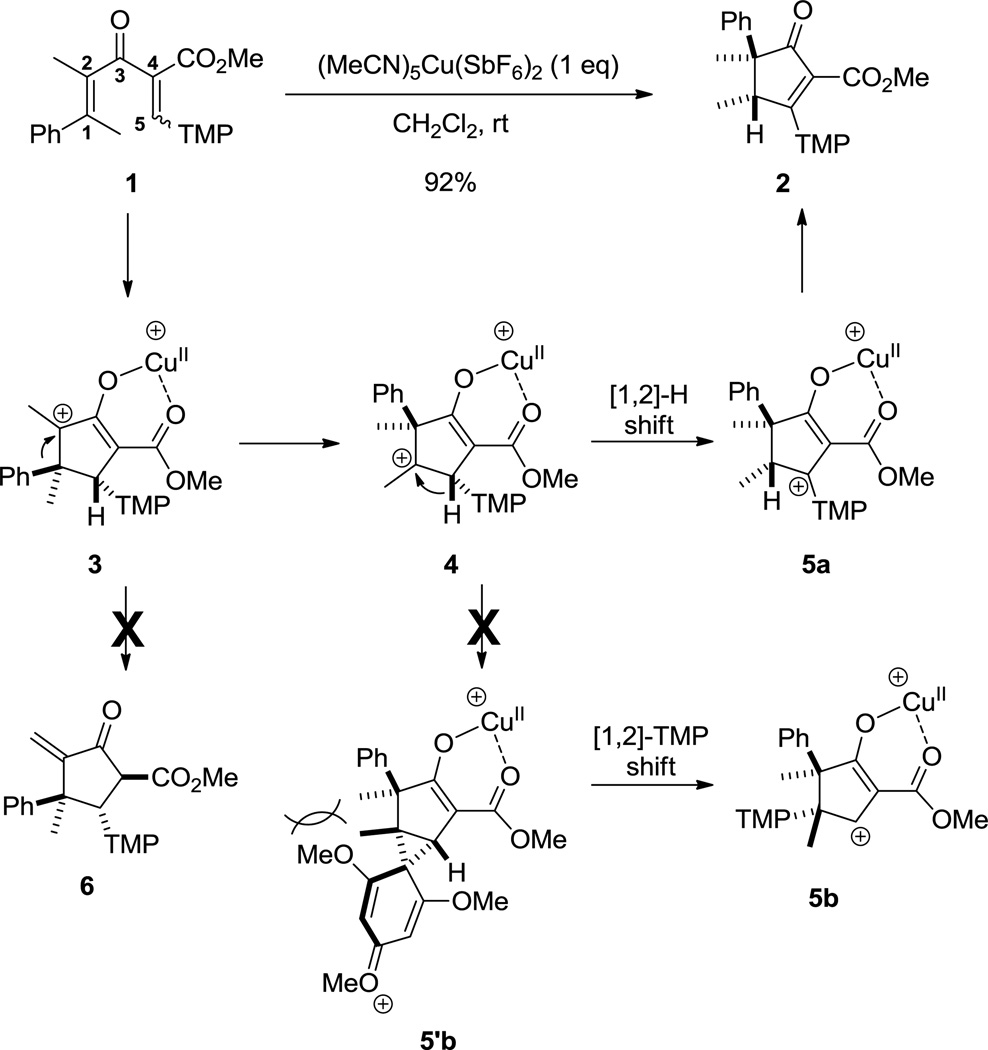

Initial experiments were focused on substrate 1 bearing a 2,4,6-trimethoxylphenyl (TMP) group at C5 (Scheme 2), because the bulk and strong electron-donating character of the TMP group increases reaction rates.4b The reaction was carried out in dichloromethane at room temperature in the presence of 100 mol% of (MeCN)5Cu(SbF6)2. Complete conversion was obtained within 5 minutes to provide cyclopentenone 2 in 92% yield as a single diastereomer. Relative stereochemistry was established by nOe analysis.

Scheme 2.

Copper-mediated cyclization of 1,4-dien-3-one 1 (TMP = 2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl).

The oxyallyl cation intermediate 3 is generated by a 4π conrotatory electrocyclization. We previously reported that the cyclization of mixtures of E and Z isomers of alkylidene β-ketoesters was stereoconvergent and occurred via an efficient isomerization process to give the product with the stereochemistry corresponding to the Z isomer cyclization, which explains the exclusive formation of intermediate 3.4b It is well-known that the migratory aptitude of aryl groups is significantly greater than that of alkyl groups,20 so it is not surprising to observe a chemoselective [1,2]-phenyl shift to give intermediate 4. After this step, either [1,2]-hydride or carbon shift can occur. An electron-donating substituent on the aryl ring enhances its migratory ability. However, the propensity for migration can also be affected by steric factors. In the case of intermediate 4, the sp2 carbon shift is presumably interrupted by the bulkiness of the 2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl, thus, cyclopentenone 2, resulting from [1,2]-hydride shift, is the only product observed. The diastereoselectivity is dictated by both the conrotatory electrocyclization and the suprafacial nature of the subsequent Wagner-Meerwein migrations. Product 6, the product expected from the conventional Nazarov cyclization/elimination sequence, is not observed.

Next, we conducted experiments to test the effect of the different substituents at C1 and C2, with a 2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl substituent at C5 (Table 1). Consistent with Scheme 2, in each case, the reaction is completely chemoselective with the exclusive migration of the R1 group and [1,2]-hydride shift from C5 to give rise to the corresponding cyclopentenones in good yields (Table 1, Entries 1–4). We noticed that the rearrangement of substrate 11 (Table 1, Entry 3) led to the formation of two products 12 and 13 in a 1:1 ratio and a combined yield of 90%, the latter corresponding to the loss of the silyl group. This deprotection could result from the presence of the hexafluoroantimonate counterion in solution.21

Table 1.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substrate | Temp (°C) | Time (h) | Product | Yield (%) |

|

|

||||

| 1 | 7 R = iPr | 25 | 0.1 | 8 | 79 |

| 2 | 9 R = Me | 25 | 0.1 | 10 | 51 |

|

|

||||

| 3 | 11 | 25 | 0.5 | 12 | 45 |

|

|||||

| 13 | 45 | ||||

|

|

||||

| 4 | 14 | 25 | 1 | 15 | 82 |

Reaction conditions: substrate in CH2Cl2 (0.03 M) in the presence of one equivalent of (MeCN)5Cu(SbF6)2 at the indicated temperature. PMP = 4-methoxyphenyl; TMP = 2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl.

We also examined the cyclization of 1,4-dien-3-ones with a phenyl group at C1 and various groups at C5, including 4-methoxyphenyl, phenyl, heteroaromatic, cinnamyl, and alkyl substituents. Almost all the reactions were carried out under refluxing conditions except for the substrates having an electron-donating 4-methoxyphenyl substituent at C5 (Table 2, Entries 4 and 5). In each case, cyclopentenones were obtained in high yields (up to 95%). In substrates 1, 16, 18, and 34, we observed the chemoselective [1,2]-shift of the phenyl from C1 to C2, and [1,2]-hydride shift from C5 to C1, consistent with the mechanism shown in Scheme 2 (Table 2, entries 1–3 and 11). However, a different reaction sequence was observed in substrates without a bulky TMP or isopropyl group at C5. In these cases, the second migration was a [1,2]-aryl or -alkenyl shift rather than a [1,2]-hydride shift (Table 2, Entries 4–10). Many of the products were obtained as mixtures of diastereomers, in ratios ranging from 4:1 to 20:1. The structures of the major products were ascertained by nOe analysis, which clearly indicated a cis-relationship between the phenyl and the alkyl moieties.

Table 2.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substrate | Temp (°C) |

Time (h) |

Product | Yield (%) |

|

|

||||

| 1 | 1 R1 = Me | 25 | 0.3 | 2 | 92 |

| 2 | 16 R1 = Et | 25 | 0.3 | 17 | 95 |

| 3 | 18 R1 = Ph | 40 | 0.5 | 19 | 95 |

|

|

||||

| 4 | 20 R1 = Me | 25 | 0.2 | 21a/21b (5:1) | 86 |

| 5 | 22 R1 = Et | 25 | 0.2 | 23a/23b (10:1) | 90 |

|

|

||||

| 6 | 24 R1 = Me | 40 | 0.5 | 25a/25b (10:1) | 85 |

| 7 | 26 R1 = Et | 40 | 0.5 | 27a/27b (10:1) | 80 |

|

|

||||

| 8 | 28 | 40 | 1 | 29a/29b (20:1) | 80 |

|

|

||||

| 9 | 30 | 40 | 1 | 31a/31b (7:1) | 95 |

|

|

||||

| 10 | 32 | 40 | 1 | 33a/33b (4:1) | 86 |

|

|

||||

| 11 | 34 | 40 | 3 | 35 (>20:1) | 68 |

Reaction conditions: substrate in CH2Cl2 (0.03 M) in the presence of one equivalent of (MeCN)5Cu(SbF6)2 at the indicated temperature. TMP = 2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl. PMP = 4-methoxyphenyl.

In the next set of experiments, the rearrangement of substrates with opposite C1–C2 double bond geometry (relative to the C1 Ph) was studied (Table 3). Interestingly, the major products obtained in most cases were the same as the ones previously observed with similar ratios (compare Table 2, Entries 4–7 and 9 with Table 3, Entries 3–7). These findings suggest that partial or complete isomerization of the C1–C2 bond occurs prior to cyclization in the presence of the copper(II) complex. Contrary to expectations, reduced chemoselectivity was observed in the rearrangement of substrate 37. Rather than exclusive migration of the phenyl group as usual (Tables 2 and 3), a 3:1 ratio of phenyl vs. ethyl migration products was observed (Table 3, Entry 2).

Table 3.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substrate | Temp (°C) | Time (h) | Product | Yield (%) |

|

|

||||

| 1 | 36 | 25 | 0.2 | 2 | 95 |

|

|

||||

| 2 | 37 | 25 | 0.2 | 19:38 (3:1) | 92 |

|

|

||||

| 3 | 39 R1 = Me | 25 | 0.5 | 21a/21b (5:1) | 88 |

| 4 | 40 R1 = Et | 25 | 0.5 | 23a/23b (7:1) | 88 |

|

|

||||

| 5 | 41 R1 = Me | 40 | 1 | 25a/25b (9:1) | 86 |

| 6 | 42 R1 = Et | 40 | 1.5 | 27a/27b (8:1) | 88 |

|

|

||||

| 7 | 43 | 40 | 1 | 31a/31b (4:1) | 89 |

Reaction conditions: substrate in CH2Cl2 (0.03 M) in the presence of one equivalent of (MeCN)5Cu(SbF6)2 at the indicated temperature. TMP = 2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl. PMP = 4-methoxyphenyl.

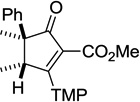

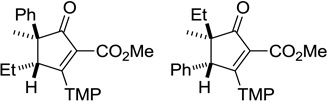

Changes in chemoselectivity were also seen in the reactions of substrates possessing steric bulk at both C1 (R1 = iPr or Ph and R2 = Ph) and C5 (R3 = aryl) (Table 4). In these substrates, the substituent with the lower migratory aptitude shifted in both the first and the second [1,2]-Wagner-Meerwein shift, compared to the corresponding substrates with less hindered pentadienyl cation termini (i.e. C1 and C5; see Tables 1–3). With R1 = Me and R2 = Me, cyclopentenone 45 was obtained in 66% yield after the expected migration of the electron-donating 4-methoxyphenyl group from C5 (Equation 1).

|

(1) |

Table 4.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substrate | Temp (°C) | Time (h) | Product | Yield (%) |

|

|

||||

| 1 | 46 | 40 | 1 | 47 | 68[a] |

|

|

||||

| 2 | 49 | 40 | 0.5 | 50 | 98 |

|

|

||||

| 3 | 51 | 40 | 1 | 52 | 70 |

|

|

||||

| 4 | 53 | 40 | 1.5 | 54 | 56 |

|

|

||||

| 5 | 55 | 40 | 2 | 56 | 89 |

Reaction conditions: substrate in CH2Cl2 (0.03 M) in the presence of one equivalent of (MeCN)5Cu(SbF6)2 at the indicated temperature. [a]: reaction in 1,2-dichloroethane. TMP = 2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl. PMP = 4-methoxyphenyl.

The other diasteromer has also been isolated in 13% yield.22

In contrast, with R1 = iPr or Ph and R2 = Ph (Table 4, Entries 1 and 3), the rearrangement led to the formation of cyclopentenones 47 and 52 after hydride migration from C5. Similarly, hydride migration was observed in hindered substrates with a thienyl or a phenyl substituent at C5 (Table 4, Entries 4 and 5). When R1 = iPr, migration of the isopropyl group rather than the phenyl group was observed from C1 (Table 4, Entries 2–5).

It is clear from the results in Tables 1–4 that different substrates follow different reaction pathways during the cyclization/rearrangement sequence. From the substrates shown in Tables 2 and 3, we know that reaction of both E and Z isomers of a substrate give the same product mixture, which demonstrates that E/Z isomerization is facile under the reaction conditions. Consistent with these findings, E/Z isomerization could be observed by 1H NMR prior to cyclization in representative cases. In contrast, E / Z isomerization was not observed in substrates with R1 = iPr (cf. Table 4, Entries 2–5 to Table 3, Entries 1, 3, 5 and 7). The steric hindrance exerted by this group seems to prevent the σ-bond rotation of C1–C2 required for the E/Z isomerization. Additional study using DFT calculations allowed further elucidation of the mechanism (vide infra.)

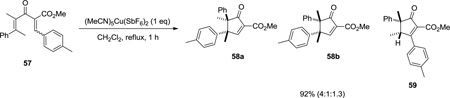

Unfortunately, this isomerization leads to the isolation of a mixture of two diastereomeric products in a number of cases. If the fidelity of the double bond geometry can be preserved during the reaction, a highly diastereoselective reaction should occur. With this goal in mind, we anticipated that placement of a bulky ligand on copper might slow down the isomerization of the double bond. To test this hypothesis, we focused on substrate 57, for which the use of (MeCN)5Cu(SbF6)2 gave rise to a mixture of the three products 58a, 58b, and 59 resulting from the isomerization of C1–C2 bond (Equation 2). In contrast, use of a bulky bidentate tBuBOX ligand allowed selective cyclization/ rearrangement of 57, producing cycloadduct 58a was isolated as the sole product (Equation 3).

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

Cyclization/rearrangement of substrate 37 (with Z geometry) was examined next. Without the bulky ligand, E/Z isomerization was observed and the chemoselectivity of the first [1,2]-shift favored the phenyl shift (Table 3, Entry 2; 3:1 ratio of 19/38). Promotion of the same reaction with tBuBox-ligated catalyst not only suppressed E/Z isomerization, but gave exclusively minor product 38 in a high yield of 91%.

|

(4) |

Thus, using the bulky tBuBox ligand prevents the isomerization of both Z and E substrates, and is also able to reverse the chemoselectivity of the [1,2]-migration.

As noted above, while the chemoselectivity of [1,2]-shifts is governed by relative migratory aptitudes in most cases (Tables 1–3), in substrates with three bulky substituents at C1 and C5 (the reacting termini of the pentadienyl cation), reaction outcomes are counter to predictions (Table 4). In these cases, other effects overrule the chemoselectivity dictated by migratory aptitude predictions. In the case of the observed migration of isopropyl rather than phenyl (Table 4, entries 2–5), we propose that the reaction is dominated by thermodynamics: equilibration of cationic intermediates 60, 61, and 62 occurs to favor formation of 62 (see computational data). In cases when a hydride migration is observed rather than an aryl migration in the second [1,2]-shift (Table 4, entries 1–5), inspection of intermediate 62 is helpful. Migration of the expected aryl group must proceed through phenonium intermediate 64, which would experience significant steric strain from both the presence of the phenonium bridge and the syn relationship of the phenyl group and the isopropyl group (Scheme 3). In comparison, the electronically disfavored hydride shift leads to 63, which lacks the steric congestion of 64.

Scheme 3.

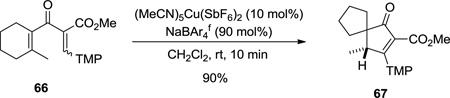

Originally, a limitation to the method was the requirement for one equivalent of a Lewis acidic promoter for efficient cyclization/ rearrangement.18, 19 With catalytic asymmetric reaction as the ultimate goal, we sought to develop a transition-metal catalyzed version of the reaction. Our observations of both cyclization and rearrangement sequences suggested that Brønsted basic species in the reaction mixture facilitate the elimination of a proton, leading to formation of the normal Nazarov cycloadduct (see Scheme 1), while coordination of the basic carbonyl lone pairs with one equivalent of the copper complex slows elimination, allowing rearrangement pathway to compete.18b Based on that model, we wanted to identify an additive that could bind to the carbonyl lone pairs of both substrate and product, could readily exchange with a reaction promoter, but would not promote the cyclization itself. Such an additive should work in combination with catalytic amount of a chiral Lewis acid to coordinate the lone pairs of the carbonyls, favoring rearrangement over elimination. In our initial attempts to achieve a catalytic rearrangement, we used a combination of 10 mol% of (MeCN)5Cu(SbF6)2 and 90 mol% of several additives such as Zn(OAc)2, Mn(acac)2, Fe(acac)2, LiClO4, Mg(OTf)2, NaSbF6, NaPF6, or NaBPh4, but these reactions were sluggish and led to mixtures of products. Furthermore, all these Lewis acids displayed poor solubility in dichloromethane. BAr4f is a highly soluble, non-coordinating counterion, and we found that LiPF6 itself promotes the cyclization, so it was not a suitable additive. Fortunately, experiments with NaBAr4f were ultimately successful.5b, 19 When dienone 66 was treated with (MeCN)5Cu(SbF6)2 (10 mol%) and NaBAr4f (90 mol%) at room temperature for 10 minutes, cyclopentenone 67 was formed in 90% yield (Equation 5). It was surprising that a sodium ion, rather than a chelating additive was sufficient for suppression of the elimination pathway. The results suggest that only one carbonyl group plays a role in the proton capture.

|

(5) |

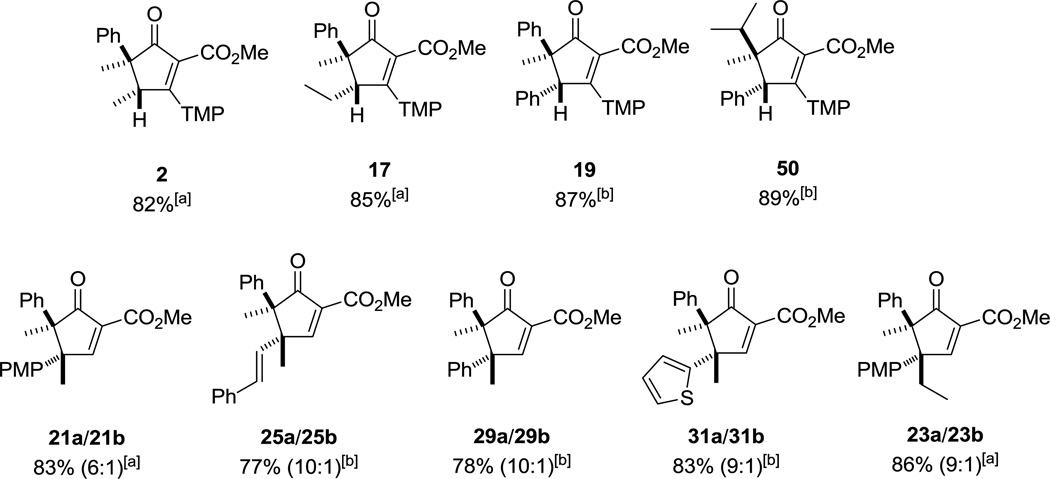

Application of these optimal reaction conditions to a representative set of substrates demonstrated that the catalytic protocol was comparable to the stoichiometric reaction (Chart 1).

Chart 1.

Copper-catalyzed cyclization of substituted 1,4-dien-3-ones.

[a] Reaction conditions: substrate in CH2Cl2 (0.03 M) in the presence of NaBAr4f (90 mol%) and (MeCN)5Cu(SbF6)2 (10 mol%) at rt for 0.1–0.5 h. [b] Reaction carried out at 45 °C. BAr4f = 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenylborate. TMP = 2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl. PMP = 4-methoxyphenyl.

Study of Reaction Pathways by Density Functional Theory

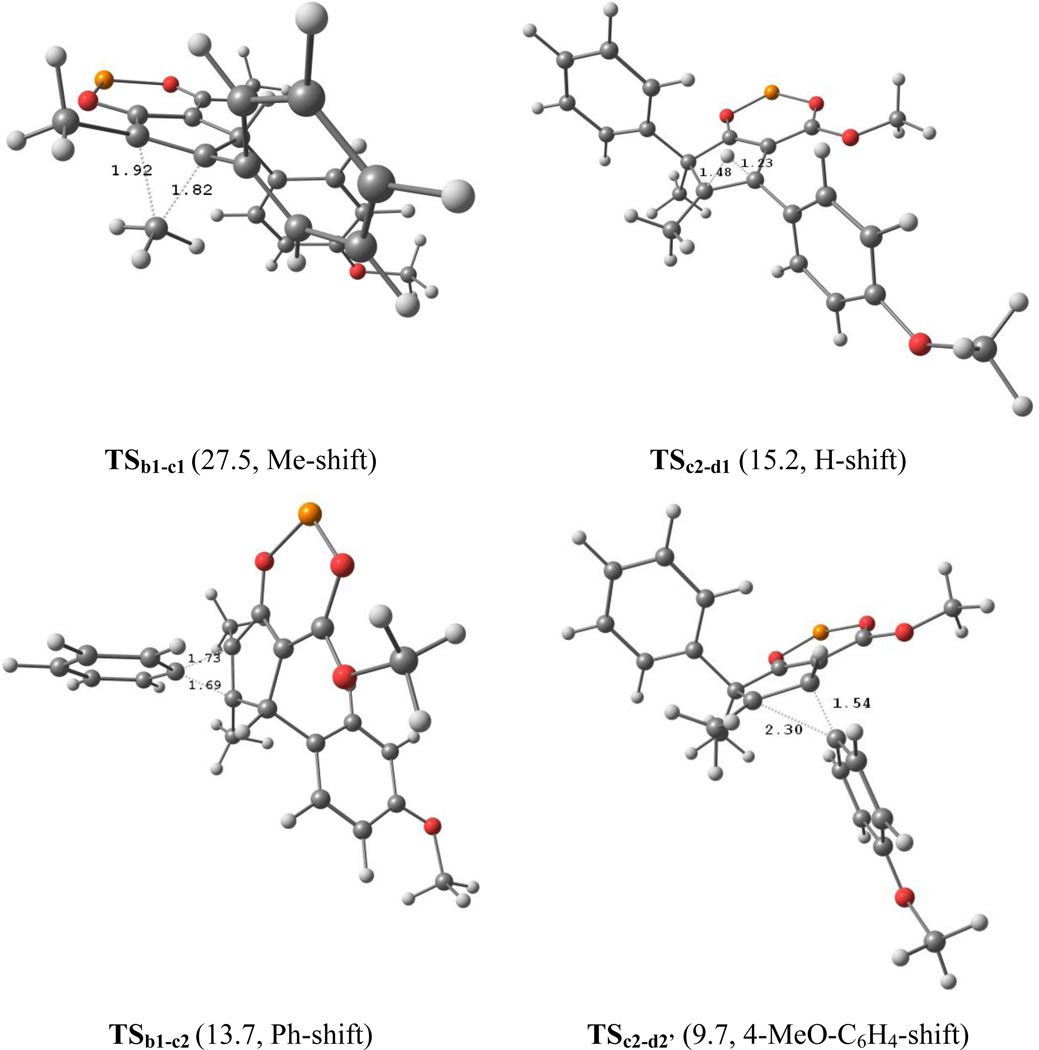

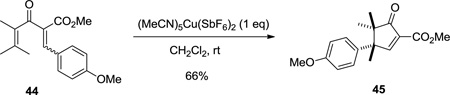

To rationalize some of the mechanistic questions raised during this study, DFT computations were carried out using dienones a1 as model substrates and Cu2+ as promoter (See Supporting Information for details).23, 24, 25 Dienones a1 are s-trans/s-trans conformers with ideal alignment for Nazarov cyclization (Scheme 4). They are taken as reference compounds (free energy of 0.0 kcal/mol). The facile E/Z isomerization of the C1–C2 double bond, observed during some of the cyclization studies (Tables 2 and 3), served as the starting point of the simulation. The calculations suggest the following sequence for the isomerization: (i) σ-bond rotation from a1 leads to s-cis/s-trans conformer a2, (ii) diastereomutation of a2 gives a3, (iii) coordination of the phenyl group of a3 to the metal center leads to a4, and (iv) a final σ-bond rotation of a4 leads to the corresponding s-trans/s-trans isomer a5, aligned for Nazarov cyclization.26

Scheme 4.

Computed intermediates for the Cu2+-mediated cyclization of dienones

Then, conrotatory 4π electrocyclization could be computed from a1 and a5, leading to oxyallyl cations b1 and b2 respectively. From these two complexes, all possible Wagner-Meerwein rearrangements were modeled (suprafacial 1,2-shifts), leading to c1–3, and then to d1–6. The latter six complexes correspond to the six possible enones e1–6 after copper dissociation.

The results are summarized in Tables 5–7, subdivided into the three main mechanistic categories (isomerization, electrocyclization, and [1,2]-shifts) for clarity. With respect to isomerization, the overall transformation of pentadienyl cation a1 into isomeric a5 is either slightly exergonic (Y = Ph, 2-thienyl, 4-MeO-C6H4) or slightly endergonic (Y = (E)-cinnamyl or TMP). In contrast, the Ph-coordinated intermediates a4 are always significantly more stable than a1, but a4 does not represent a deep potential well. In each Y series, the rate-determining step is the diastereomutation itself (a2→a3), as one would expect, rather than any conformational interconversion. Those high-lying transition states show a virtually perpendicular arrangement of the PhC1R and the MeC2C planes (see Figure 1 with Y = 4-MeO-C6H4 and R = Me, MeC1C2Me = 79°).

Table 5.

Computed free energies for the isomerization process at 298K (UB3LYP/6-31G**//PCM correction, kcal/mol) relative to a1 for the a1→a5 transformation (free energies of activation are displayed in italics).

| Isomerization | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a1→a2 | a2→a3 | a3→a4 | a4→a5 | ||||||

| Entry | ΔG‡ | ΔG | ΔG‡ | ΔG | ΔG‡ | ΔG | ΔG‡ | ΔG | |

| 1 | Y = Ph, R = Me | 8.8 | 1.4 | 12.1 | -[a] | - | −8.4 | 3.5 | −2.7 |

| 2 | Y = 2-thienyl, R = Me | 5.6 | 1.4 | 15.4 | 0.6 | 3.6 | −7.8 | 1.5 | −0.6 |

| 3 | Y = (E)-cinnamyl, R = Me | 0.1 | 2.3 | 17.8 | -[a] | - | −5.5 | 2.4 | 0.2 |

| 4 | Y = 4-MeO-C6H4, R = Me | 10.3 | 2.6 | 18.6 | −0.9 | 4.0 | −7.0 | 4.7 | −1.4 |

| 5 | Y = TMP, R = Me | 9.0 | −0.6 | 19.1 | 1.0 | 4.8 | −6.4 | 1.4 | 2.0 |

| 6 | Y = TMP, R = Et | 9.3 | −6.1 | 24.6 | 0.8 | 2.4 | −5.4 | 6.8 | 3.0 |

| 7 | Y = TMP, R = iPr | 7.9 | 5.1 | -[b] | −0.6 | 1.8 | −7.6 | 8.9 | −0.8 |

No convergence of this intermediate, direct collapse to the next one.

Could not be located on the PES.

Table 7.

Computed free energies for the electrocyclization and the [1,2] shifts at 298 K (UB3LYP/6-31G**//PCM correction, kcal/mol), relative to a1 with R = Me (free energies of activation are displayed in italics).

| Entry | Y = Ph | Y = (E)-cinnamyl | Y = 4-MeO-C6H4 | Y = TMP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG‡ | ΔG | ΔG‡ | ΔG | ΔG‡ | ΔG | ΔG‡ | ΔG | ||

| Nazarov | |||||||||

| 1 | a1→b1 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 21.0 | 18.4 | 15.5 | 12.6 | 19.0 | 8.7 |

| 2 | a5→b2 | 13.0 | 5.7 | 23.3 | 20.8 | 18.7 | 13.3 | 25.7 | 19.7 |

| Shifts | |||||||||

| 3 | b1→c1 (1,2-Me shift) | 10.6 | −8.1 | 27.7 | 5.7 | 18.6 | 0.4 | 27.5 | 3.0 |

| 4 | b2→c1 (1,2-Me shift) | 7.9 | −8.1 | 33.6 | 5.7 | 22.2 | 0.4 | 25.9 | 3.0 |

| 5 | b1→c2 (1,2-Ph shift) | 5.4 | 2.2 | 18.6 | -[a] | 13.7 | 11.3 | 19.1 | 8.5 |

| 6 | b2→c3 (1,2-Ph shift) | 3.5 | 3.6 | 19.3 | 18.4 | 15.0 | 5.0 | 23.7 | 12.3 |

| 7 | c1→d3 (1,2-Y shift) | 2.3 | −3.7 | 7.8 | 10.8 | 3.9 | 1.7 | 8.9 | 2.7 |

| 8 | c1→d4 (1,2-H shift) | 6.6 | −20.9 | 19.0 | −14.0 | 2.7 | −18.9 | 17.1 | −14.0 |

| 9 | c2→d1 (1,2-H shift) | 8.9 | −15.6 | - | −14.8 | 15.2 | −11.3 | 17.6 | −11.3 |

| 10 | c2→d2 (1,2-Y shift) | 7.8 | −4.2 | - | −0.3 | 9.7 | 6.3 | 14.2 | 9.4 |

| 11 | c3→d5 (1,2-Y shift) | 7.8 | −2.2 | 17.4 | 5.7 | 9.5 | 7.4 | 15.4 | 7.3 |

| 12 | c3→d6 (1,2-H shift) | 8.6 | −14.4 | 21.3 | −17.7 | 15.1 | −10.7 | 17.4 | −6.0 |

No convergence of this intermediate, direct collapse to d2.

Figure 1.

Geometries and energies of the species involved in the a1→a5 transformation with Y = 4-MeO-C6H4 and R = Me (UB3LYP/6-31G**//PCM correction, kcal/mol)

Electron-withdrawing Y groups are expected to assist the isomerization process by lowering the C1–C2 bond order, as in resonance form a2”. On the other hand, electron-donating groups should favor a2’ and make the isomerization more difficult (Equation 6).

|

(6) |

In the phenyl series, the substrate with Y = TMP has a high inversion barrier, calculated at 19.1 kcal/mol (Table 5, Entry 5). The relationship between the inversion barrier and the electronic nature of the Y group is displayed in Table 6. As the energy required to reach TSa2–a3 increases, the C1–C2 bond order increases while the C1–C2 bond distance and the natural charge at C1 both decrease. These values indicate that the most important resonance form of a2 should be a2’ when Y = TMP.

Table 6.

Relationship between the a2→a3 free energies of activation (UB3LYP/6-31G**//PCM correction, kcal/mol) and the polarization of the C1–C2 bond in a2.

| Entry | Y | ΔG‡ | C1C2 (Å) | Natural charge at C1[a] |

Wiberg bond index[a] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C6H5 | 12.1 | 1.429 | 0.200 | 1.35 |

| 2 | 4-MeO-C6H4 | 18.6 | 1.402 | 0.176 | 1.49 |

| 3 | TMP | 19.1 | 1.373 | 0.07 | 1.62 |

Natural charges and Wiberg bond indices were calculated from NBO theory.27

Notably, the steric hindrance at C1 also plays a dramatic influence on the isomerization rate. For example, when R = Me is changed to R = Et, the free energy of activation of the a2→a3 step increases by more than 4 kcal/mol to reach 24.6 kcal/mol (Table 5, Entries 5 and 6). When R = iPr (Table 5, Entry 7), it was no longer possible to find the isomerization transition state, presumably because it is too high in energy. The absence of an isomerization transition state on the potential energy surface when R = iPr is consistent with the 100% stereoselective transformation of 49 into 50 (Table 4, Entry 3).

The rest of the mechanistic scenario depicted in Scheme 4 was computed for R = Me and Y = Ph, (E)-cinnamyl, 4-MeOC6H4, and TMP (Table 7). The 4π electrocyclizations were all found to be endergonic. Nevertheless, those leading to the less sterically congested isomer b1 are always kinetically and thermodynamically favored over those leading to b2 (Table 7, Entries 1 and 2). Again, the magnitude of the activation barriers is critically dependent on the nature of Y. Electron-donating groups appear to raise the barrier for electrocyclization process (e.g. 4.1 for Y = Ph vs 15.5 kcal/mol for Y = 4-MeO-C6H4), probably because these groups stabilize the pentadienyl cation.28

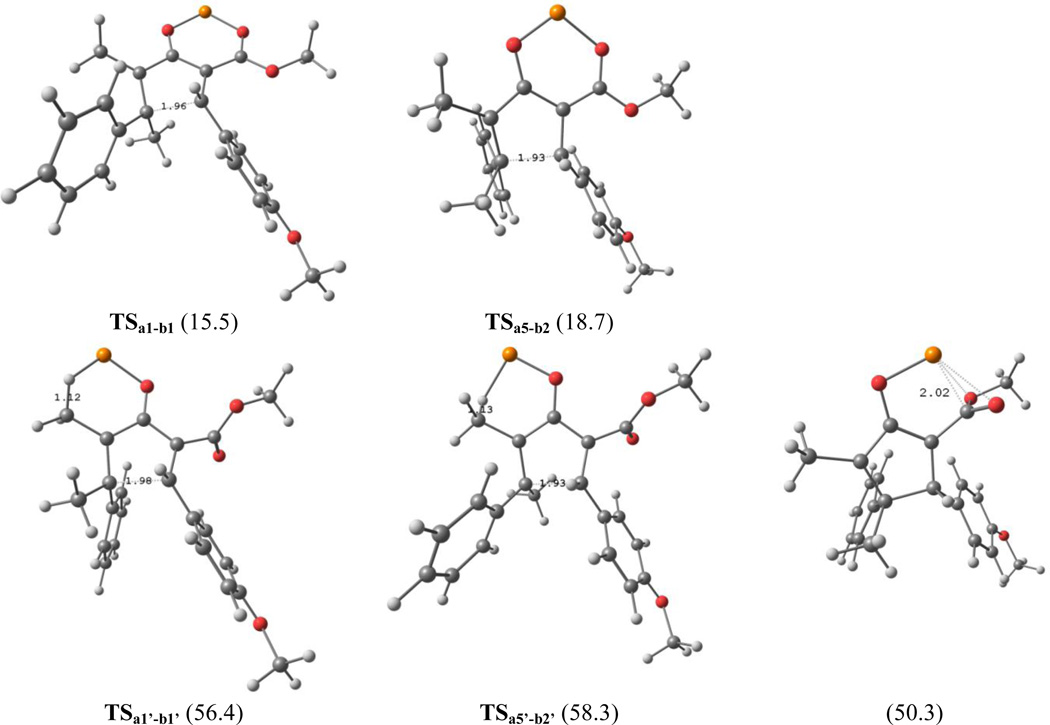

Recently, the decomplexation of copper from the carbonyl oxygens of alkylidene β-ketoesters and oxazolidinones, resulting in an out-of-plane orientation of the C4 carbonyl, has been proposed to explain the stereochemical outcome of some copper(II)-catalyzed Nazarov cyclizations.3m To examine this proposal in the context of our system, TSa1–b1 and TSa5–b2 were recomputed in the 4-MeO-C6H4 series after decomplexation of copper from the ester functionality. In the new transition states TSa1’–b1’ and TSa5’–b2’, the metal establishes an agostic interaction with the methyl group at C2 (see Figure 2). However, the energies of these species relative to a1 are much higher than those of TSa1–b1 and TSa5–b2 (56.4 and 58.3 kcal/mol respectively). An η3-dioxyallyl copper complex was also envisaged, yet we could not locate any electrocyclization transition state. Instead, a species corresponding to the rotation of the ester moiety converged. Again, this transformation requires a prohibitive free energy of activation of 50.3 kcal/mol. Thus, in both of the cases we modelled, dechelation is unlikely. Additional calculations using ligated copper (II) ((CH3CN)2Cu2+)) instead of (Cu (II)2+) did not allow optimization of these high-lying transition states either (vide infra).

Figure 2.

Electrocyclization and ester rotation transition states (UB3LYP/6-31G**//PCM correction, kcal/mol) for Y = 4-MeO-C6H4 and R = Me (distances in Å)

With respect to the [1,2]-shifts, the computations are in good agreement with the expected migratory aptitudes of methyl, hydride, phenyl or Y (Figure 3). For instance, the initial methyl shifts leading from b1/ b2 to c1 (Table 7, Entries 3 and 4) require a considerably higher free energy of activation than the corresponding phenyl shifts (b1 to c2 or b2 to c3; Table 8, Entries 5 and 6). For the subsequent step (from c2/ c3 to intermediates d) the [1,2] shifts of Y groups are kinetically favored over [1,2]-hydride shifts (Table 7, Entries 10 and 11 vs. Entries 9 and 12).

Figure 3.

Geometry of selected [1,2]-shift transition states (UB3LYP/6-31G**//PCM correction, kcal/mol) for R = Me (distances in Å)

The geometries of the cyclopentenyl cations of type d also warrant comment. Indeed, the electron-deficient center C5 may receive electron density from the phenyl or the Y groups. This interaction is particularly obvious when Y = (E)-cinnamyl, 4-MeO-C6H4, and TMP, which converge as bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane derivatives (see d2’, d3’, and d5’).29 For example, as shown in Scheme 4, when Y = Ph the carbocationic center is clearly located on C5, but delocalized throughout the π-system of the other electron-rich groups, including the (E)-cinnamyl group. In spite of our efforts, it was not possible to find minima representing both d and d’ within the same series (Figure 4). This suggests that the bicyclic structure is always more stable than the localized secondary carbocation. Although much weaker, this neighbouring stabilization effect is also present in other intermediates, such as b2 (tertiary carbocation at C2), c2 and c3 (tertiary carbocation at C1) (see Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

Geometry of d2 and d2’ cations (UB3LYP/6-31G**//PCM correction, distances in Å).

To save computer time, all the calculations presented above involve unligated copper (II). It is quite clear that some of the computational results may change with the introduction of ligands, notably regarding the π-complexes a4 and the agostic complexes shown in Figure 2. To address this issue, the computations related to the 4-MeO-C6H4 series were repeated with two acetonitrile units on Cu (Scheme 5). As expected, intermediate a4 is no longer observed in the a1→a5 sequence. However, the isomerization transition state connecting a2 and a3 remains the highest-lying (25.7 kcal/mol), a value that is actually higher than those of the electrocyclization steps leading to b1 and b2 (18.3 and 20.3 kcal/mol respectively). Complex b1 remains kinetically and thermodynamically favored over b2, since the electrocyclization steps are still endergonic, and the methyl shifts leading to c1 remain slower than the phenyl shifts. In contrast with the unligated series, c2 and c3 do not converge. They collapse directly to d2 and d5, with the migration of the phenyl group immediately followed by migration of the PMP. This finding is not unique to the calculations with ligated copper, since c2 is also absent from the potential energy surface in the (E)-cinnamyl series (see Table 7). With acetonitrile ligands, the structures of d2, d3, and d5 are quite distinct from the corresponding ones in the unligated series (phenoniums d2’, d3’, d5’; Scheme 4). This may be because the [(MeCN)2Cu] moiety is more electron-rich, so the backdonation towards the organic backbone becomes more efficient. The stabilization of the charge at C5 (see d2, Scheme 5) by the adjacent PMP (i.e. the phenonium) is no longer required since the metal can now accommodate two formal charges, leading to Lewis structures that are much more like the final products. Despite these geometrical differences, the shifts leading to d2 remain the most kinetically favorable, and d2 represents the framework of the product experimentally obtained. Thus, both sets of calculations, using either (MeCN)2Cu]2+ or the simpler unligated copper(II), predict the same experimental outcome. It is nonetheless interesting to note the favorable effect the ligands have on the migration at C5.

Scheme 5.

Computed intermediates for the Cu2+-mediated cyclization of dienones with Y = 4-MeO-C6H4 (PMP) and acetonitrile on Cu (UB3LYP/6-31G**//PCM correction, kcal/mol)

Summary, Conclusions and Perspectives

In summary, we have developed a diastereoselective method for preparation of highly functionalized cyclopentenones based on a copper(II)-promoted Nazarov/Wagner-Meerwein sequence. The scope of the reaction is broad, allowing preparation of products with adjacent stereogenic centers, and in some cases, adjacent quaternary centers. The reaction was always efficient using a stoichiometric amount of a copper-(II) complex, and in many cases it was possible to lower the amount of copper to 10 mol% by adding a sodium salt to attenuate the basicity of the carbonyl oxygen. Although chemoselectivity of the sequential [1,2] shifts is typically high, predicting the structures of the products is not as simple as one might expect. Sometimes the chemoselectivity is governed by relative migratory aptitude, and sometimes we find that other factors overwhelm these propensities, leading to the selective formation of an isomer with unexpected connectivity. Isomerization of the Nazarov cyclization substrate is another complication in some cases, which also makes prediction of product stereochemistry difficult. DFT calculations have helped us to gain mechanistic insight into the substrate isomerization and to understand the factors dictating selectivity in the cation rearrangements. Furthermore, we found it was possible to prevent the isomerization with the use of a bisoxazoline ligand on the copper (II) complex, allowing controlled, predictable electrocyclization of enone substrates with the expected stereospecificity. Ongoing research in the laboratory is focused upon the development of an asymmetric version of this reaction and application of this strategy towards the synthesis of natural products.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the National Science Foundation (Grant CHE-0847851, supporting D. L.) and the National Institutes of Health (NIGMS R01 GM079364, supporting J. C.) for funding this work. We used the computing facility of the CRIHAN (project 2006-013). We thank Prof R. Eisenberg (University of Rochester) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available.

Complete reference 23, experimental procedures and characterization data for all new compounds are available free of charge via the Internet http://pubs.acs.org.

Contributor Information

Vincent Gandon, Email: vincent.gandon@u-psud.fr.

Alison J. Frontier, Email: frontier@chem.rochester.edu.

References

- 1.(a) Woodward RB, Hoffmann R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1969;8:781. [Google Scholar]; (b) Woodward RB, Hoffmann R. The Conservation of Orbital Symmetry. Verlag Chemie: Weinheim; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Santelli-Rouvier C, Santelli M. Synthesis. 1983:429. [Google Scholar]; (b) Habermas KL, Denmark SE, Jones TK. In: Organic Reactions. Paquette LA, editor. Vol. 45. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1994. pp. 1–158. [Google Scholar]; (c) Harmata M. Chemtracts. 2004;17:416. [Google Scholar]; (d) Pellissier H. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:6479. [Google Scholar]; (e) Frontier AJ, Collison C. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:7577. [Google Scholar]; (f) Tius MA. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005;11:2193. [Google Scholar]; (g) Nakanishi N, West FG. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev. 2009;12:732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Shimada N, Stewart C, Tius MA. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:5881. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Vaidya T, Eisenberg R, Frontier AJ. Chem Cat Chem. 2011;3:1531. [Google Scholar]

- 3.For recent examples of Nazarov cyclizations, see: Williams DR, Robinson LA, Nevill CR, Reddy JP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:915. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603853. He W, Huang J, Sun X, Frontier AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:300. doi: 10.1021/ja0761986. Marcus AP, Lee AS, Davis RL, Tantillo DJ, Sarpong R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6379. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801542. Amere M, Blanchet J, Lasne MC, Rouden J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:2541. Kokubo M, Kobayashi S. Chem. Asian J. 2009;4:526. doi: 10.1002/asia.200800461. Rieder CJ, Winberg KJ, West FG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:7504. doi: 10.1021/ja9023226. Malona JA, Cariou K, Frontier AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:7560. doi: 10.1021/ja9029736. Singh R, Parai MK, Panda G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:1858. doi: 10.1039/b901632e. Cordier P, Aubert C, Malacria M, Lacôte E, Gandon V. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:8757. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903675. Wang M, Han F, Yuan H, Liu Q. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:2247. doi: 10.1039/b917703e. Wender PA, Stemmler RT, Sirois LE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2532. doi: 10.1021/ja910696x. Murugan K, Srimurugan S, Chen C. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:1127. doi: 10.1039/b918137g. Kerr DJ, White JM, Flynn BL. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:7073. doi: 10.1021/jo100736p. Marcus AP, Sarpong R. Org. Lett. 2010;12:4560. doi: 10.1021/ol1018536. Cai Z, Harmata M. Org. Lett. 2010;12:5668. doi: 10.1021/ol102478h. Hastings CJ, Pluth MD, Bergman RG, Raymond KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:6938. doi: 10.1021/ja102633e. Rieder CJ, Winberg KJ, West FG. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:50. doi: 10.1021/jo101497f. Spencer WT, III, Levin MD, Frontier AJ. Org. Lett. 2011;13:414. doi: 10.1021/ol1027255. Li W-DZ, Duo WG, Zhang CH. Org. Lett. 2011;13:3538. doi: 10.1021/ol201390r. Brooks JL, Caruana PA, Frontier AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:12454. doi: 10.1021/ja205440x.

- 4.Cu(II): He W, Sun X, Frontier AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:14278. doi: 10.1021/ja037910b. He W, Herrick IR, Atesin TA, Caruana PA, Kellenberger CA, Frontier AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1003. doi: 10.1021/ja077162g.

- 5.Pd(II): Bee C, Leclerc E, Tius MA. Org. Lett. 2003;5:4927. doi: 10.1021/ol036017e. Zhang J, Vaidya T, Brennessel WW, Frontier AJ, Eisenberg R. Organometallics. 2010;29:3541. Subramanium SS, Handa S, Miranda AJ, Slaughter LM. ACS Catal. 2011;1:1371.

- 6.Sc(III): Larini P, Guarna A, Occhiato EG. Org. Lett. 2006;8:781. doi: 10.1021/ol053071h. Malona JA, Colbourne JM, Frontier AJ. Org. Lett. 2006;8:5661. doi: 10.1021/ol062403v. Bitar AY, Frontier AJ. Org. Lett. 2009;11:49. doi: 10.1021/ol802329y.

- 7.IR(III): Janka M, He W, Frontier AJ, Eisenberg R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:6864. doi: 10.1021/ja049643v. Janka M, He W, Frontier AJ, Flaschenriem C, Eisenberg R. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:6193. Vaidya T, Atesin AC, Herrick IR, Frontier AJ, Eisenberg R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:3363. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000100. Atesin AC, Zhang J, Vaidya T, Brennessel WW, Frontier AJ, Eisenberg R. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:4331. doi: 10.1021/ic100300y.

- 8.V(IV): Walz I, Bertogg A, Togni A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007:2650.

- 9.Au(I) or Au(III): Zhang L, Wang S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:1442. doi: 10.1021/ja057327q. Jin T, Yamamoto Y. Org. Lett. 2008;10:3137. doi: 10.1021/ol801265s. Lemière G, Gandon V, Cariou K, Hours A, Fukuyama T, Dhimane A-L, Fensterbank L, Malacria M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2993. doi: 10.1021/ja808872u. Krafft ME, Vidhani DV, Cran JW, Manoharan M. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:6707. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10920k.

- 10.Fe(II) or Co(I): Kawatsura M, Higuchi Y, Hayase S, Nanjo M, Itoh T. Synlett. 2008:1009. Kawatsura M, Kajita K, Hayase S, Itoh T. Synlett. 2010:1243.

- 11.Pt(II): Zheng H, Xie X, Yang J, Zhao C, Jing P, Fang B, She X. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:7555. doi: 10.1039/c1ob06138k.

- 12.(a) Pridgen LN, Huang K, Shilcrat S, Tickner-Eldridge A, DeBrosse C, Haltiwanger RC. Synlett. 1999:1612. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tius MA, Harrington PE. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2447. doi: 10.1021/ol0001362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Harrington PE, Murai T, Chu C, Tius MA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:10091. doi: 10.1021/ja020591o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kerr DJ, Metje C, Flynn BL. Chem. Commun. 2003:1380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Banaag AR, Tius MA. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:8133. doi: 10.1021/jo801503c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Aggarwal VK, Belfield AJ. Org. Lett. 2003;5:5075. doi: 10.1021/ol036133h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liang G, Trauner D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9544. doi: 10.1021/ja0476664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Walz I, Togni A. Chem. Commun. 2008:4315. doi: 10.1039/b806870d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rueping M, Ieawsuwan W. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009;351:78. [Google Scholar]; (e) Yaji K, Shindo M. Synlett. 2009:2524. [Google Scholar]; (f) Cao P, Deng C, Zhou Y-Y, Sun XL, Zheng J-C, Xie W, Tang Y. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:4463. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Rueping M, Ieawsuwan W, Antonchick AP, Nachtsheim BJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:2097. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bow WF, Basak AK, Jolit A, Vicic DA, Tius MA. Org. Lett. 2010;12:440. doi: 10.1021/ol9025765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Basak AK, Shimada N, Bow WF, Vicic DA, Tius MA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8266. doi: 10.1021/ja103028r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.For a review, see: Grant TN, Rieder CJ, West FG. Chem. Commun. 2009:5676. doi: 10.1039/b908515g. and references cited therein. For other relevant examples, see: Janka M, He W, Haedicke IE, Fronczek FR, Frontier AJ, Eisenberg R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:5312. doi: 10.1021/ja058772o. Dhoro F, Kristensen TE, Stockmann V, Yap GPA, Tius MA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7256. doi: 10.1021/ja0718873. Nie J, Zhu HW, Cui HF, Hua MQ, Ma JA. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3053. doi: 10.1021/ol071114j. Fujiwara M, Kawatsura M, Hayase S, Nanjo M, Itoh T. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009;351:123. Marx VM, Cameron TS, Burnell DJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:7213. Marx VM, Burnell DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;11:1685. doi: 10.1021/ja909073r. Rieder CJ, Fradette RJ, West FG. Heterocycles. 2010;80:1413. Scadeng O, West FG. Org. Lett. 2011;13:114. doi: 10.1021/ol102651k. Marx VM, LeFort FM, Burnell DJ. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011;353:64. Wu Y-K, McDonald R, West FG. Org. Lett. 2011;13:3584. doi: 10.1021/ol201125h. Marx VM, Stoddard RL, Heverly-Coulson GS, Burnell SJ. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:8098. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100519. Rueping M, Ieawsuwan W. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:11450. doi: 10.1039/c1cc15289k.

- 16.Ohloff G, Schulte-Elte KH, Demole E. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1971;54:2913. [Google Scholar]; (b) Paquette LA, Fristad WE, Dime DS, Bailey TR. J. Org. Chem. 1980;45:3017. [Google Scholar]; (c) Denmark SE, Hite GAG. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1988;71:195. [Google Scholar]; (d) Motoyoshiya J, Yazaki T, Hayashi S. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:735. [Google Scholar]; (e) Gruhn AG, Reusch W. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:8159. [Google Scholar]; (f) Kuroda C, Koshio H, Koito A, Sumiya H, Murase A, Hirono Y. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:6441. [Google Scholar]; (g) Chiu P, Li SL. Org. Lett. 2004;6:613. doi: 10.1021/ol036433z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.For recent reviews, see: Wendt KU, Schulz GE, Corey EJ, Liu DR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:2812. Yoder RA, Johnston JN. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:4730. doi: 10.1021/cr040623l. Christianson DW. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3412. doi: 10.1021/cr050286w. Tantillo DJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:2847. doi: 10.1039/b917107j. Tantillo DJ. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011;28:1035. doi: 10.1039/c1np00006c. and references cited therein.

- 18.(a) Huang J, Frontier AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:8060. doi: 10.1021/ja0716148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huang J, Leboeuf D, Frontier AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:6307. doi: 10.1021/ja111504w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lebœuf D, Huang J, Gandon V, Frontier AJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:10981. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Bachmann WF, Ferguson JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1934;56:2081. [Google Scholar]; (b) Collins CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955;77:5517. [Google Scholar]; (c) Owen JR, Saunders WH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966;88:5809. [Google Scholar]; (d) Heidke RL, Saunders WH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966;88:5816. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brimble MA, Crimmins D, Trzoss M. Arkivoc. 2005;i:39. [Google Scholar]

-

22.The following minor product was obtained with a yield of 13%:

- 23.Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 03 (v C02) Wallingford CT: Gaussian, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.The geometry optimizations and thermodynamic corrections were performed with hybrid density functional theory (UB3LYP, doublet spin state for Cu, +2 overall charge) with the 6–31G(d,p) basis set. The choice of this functional and basis set is justified in the Computational Methods section of ref 25a (see references therein). The B3LYP functional was also used in ref 25b. The spin contamination was checked from the final value of <Ŝ2>for all structures and found to be very small (< 0.76). Intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations utilized the default implementation. They were carried out in the Y = Ph and Y = PMP series. Solvation corrections for dichloromethane were computed using the polarizable continuum model (PCM) with UFF radii using the gas phase optimized structures. All relative energies presented in this manuscript are free energies (ΔG) in kilocalories per mole. Solvation free energies were calculated by adding the solvation energies to the computed gas phase relative free energies (ΔG298). Wiberg bond indices were calculated from NBO theory as implemented in Gaussian.

- 25.For rare theoretical reports on Cu2+-mediated Nazarov reactions, see: Mayoral JA, Rodríguez-Rodríguez S, Salvatella L. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:9274. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800638. Cao P, Deng C, Zhou Y-Y, Sun X-L, Zheng J-C, Xie Z, Tang Y. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:4463. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907266. For selected theoretical reports on H+-mediated Nazarov reactions, see: (c) Nieto Faza O, Silva López C, Álvarez R, de Lera AR. Chem. Eur. J. 2004;10:4324. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400037. Cavalli A, Masetti M, Recanatini M, Prandi C, Guarna A, Occhiato EG. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:2836. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501391. Polo V, Andrés J. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2007;3:816. doi: 10.1021/ct7000304. Cavalli A, Pacetti A, Recanatini M, Prandi C, Scarpi D, Occhiato EG. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:9292. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801030. Davis RL, Tantillo DJ. Curr. Org. Chem. 2010;14:1561. For a theoretical report on the retro-Nazarov reaction, see: (h) Harmata M, Schreiner PR, Lee DR, Kirchhoefer PL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:10954. doi: 10.1021/ja048942h.

- 26.Some minor conformational rearrangements with very low free energy of activations have been omitted for clarity.

- 27.(a) Wiberg KB. Tetrahedron. 1968;24:1083. [Google Scholar]; (b) Foster JP, Weinhold F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:7211. [Google Scholar]; (c) Reed AE, Weinstock RB, Weinhold F. J. Chem. Phys. 1985;83:735. [Google Scholar]; (d) Weinhold F, Carpenter JE. In: The Structure of Small Molecules and Ions. Naaman R, Vager Z, editors. Plenum; 1988. p. 227. [Google Scholar]

- 28.For the influence of electronic effect on the Nazarov cyclization, see: Jones TK, Denmark SE. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1983;66:2377. Jones TK, Denmark SE. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1983;66:2397. Denmark SE, Habernas KL, Hite GA. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1988;71:168. Denmark SE, Klix RC. Tetrahedron. 1988;44:4043. Denmark SE, Wallace MA, Walker CB. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:5543.

- 29.(a) Cram DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949;71:3863. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cram DJ, Davis R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949;71:3871. [Google Scholar]; (c) Cram DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949;71:3875. [Google Scholar]; (d) Cram DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964;86:3767. [Google Scholar]; (e) Brown HC, Morgan KJ, Chloupek FJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965;87:2137. [Google Scholar]; (f) Vogel P. Carbocation Chemistry. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1985. Chapter 7. [Google Scholar]; (g) Olah GA, Porter RD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970;92:7627. [Google Scholar]; (h) Del Rio E, Menendez MI, Lopez R, Sordo TL. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2000;104:5568. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.