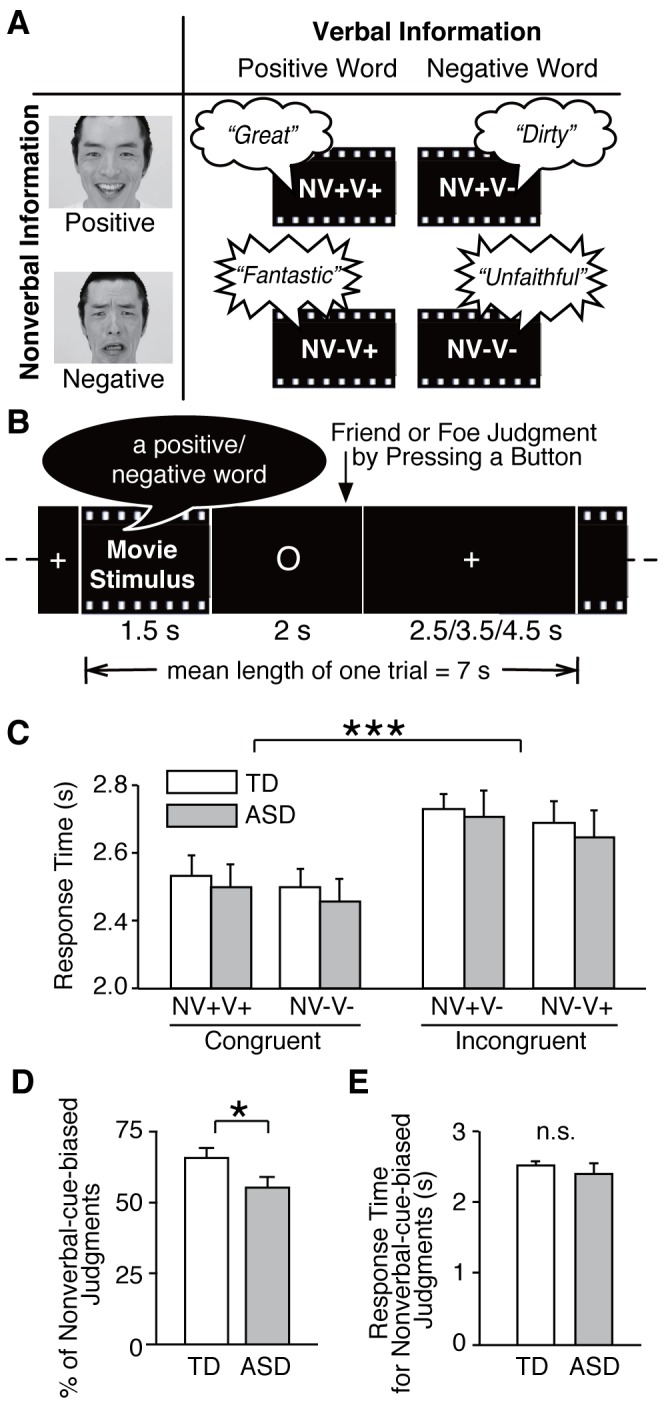

Figure 1. Task design and behavioral results.

(A) Short movie stimuli. Our stimuli were short movies in which different professional actors spoke different emotional words (verbal information; positive and negative) while displaying different emotional facial expressions and voice prosody (nonverbal information; positive and negative). The emotional valence of the facial expressions was always the same as that of the voice prosody. Overall, the stimuli consisted of two types of congruent short movies (NV+V+: positive nonverbal and positive verbal information; NV-V-: negative nonverbal and negative verbal information) and two types of incongruent ones (NV+V-: positive nonverbal and negative verbal information; NV-V+: negative nonverbal and positive verbal information). (B) Task design. One trial of fMRI scanning session consisted of a 1.5 sec movie stimulus period, 2 sec response period, and a 2.5,3.5, or 4.5 sec fixation period. Participants were instructed to judge the person in each movie as friend or foe by pressing the corresponding buttons. (C) Response times. In a repeated-measure mixed-design two-way ANOVA, there was no significant main effect of group (TD versus ASD) on response time, whereas there was a significant main effect of stimulus type (congruent versus incongruent). Response times for the incongruent stimuli were significantly longer than that for the congruent stimuli (***: P<0.001). To present the data, we further divided the stimulus types into more detailed categories. (D) Number of nonverbal-cue-biased judgments. ASD individuals exhibited significantly fewer nonverbal-cue-biased judgments of incongruent stimuli than the TD individuals (*:P<0.05) (E) Response times for nonverbal-cue-biased judgments. There was no significant difference in response time for nonverbal-cue-biased judgments of incongruent stimuli between the ASD and TD groups.