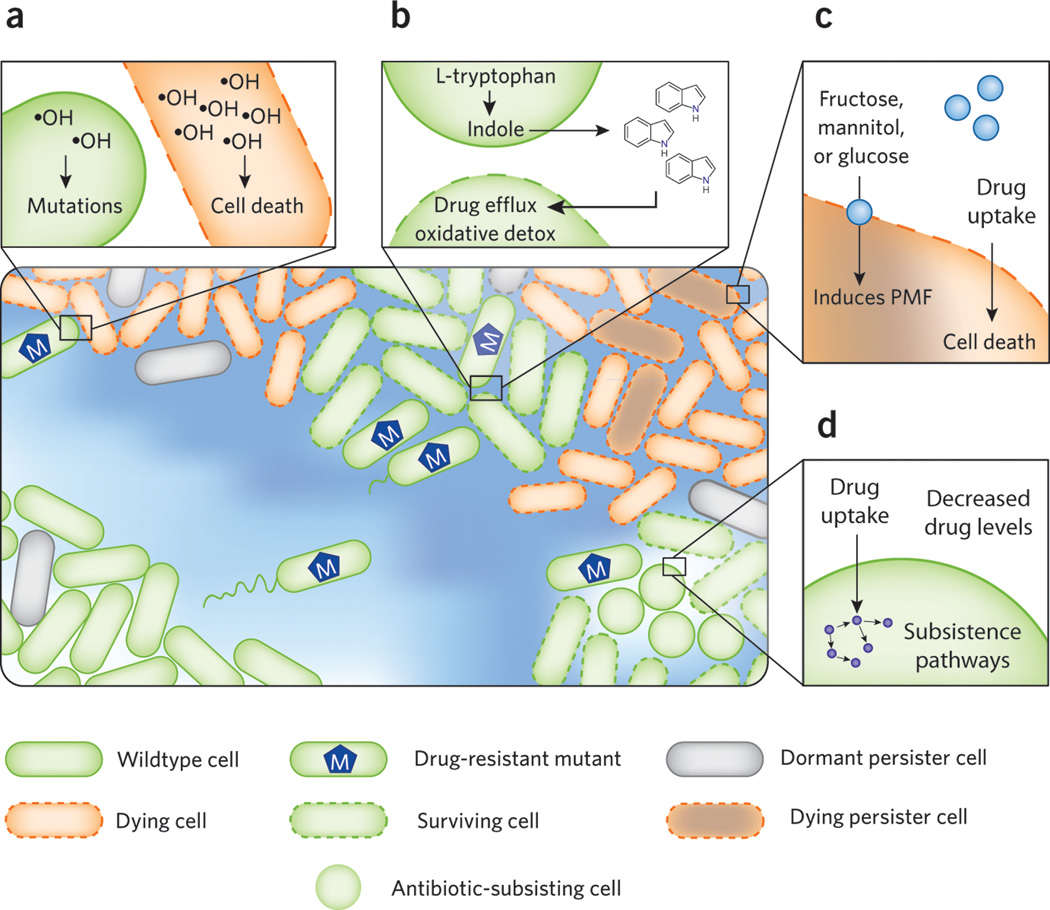

Figure 1. Microbial environments enable antibiotic resistance and tolerance.

A bacterial population subjected to a gradient of antibiotic concentration is shown in the main figure. (a) Antibiotics induce formation of deleterious hydroxyl radicals. Under sublethal antibiotic stress, these mutagenic hydroxyl radicals promote the emergence of antibiotic-resistant mutants. Lethal concentrations of antibiotic lead to high levels of hydroxyl radicals, which contribute to antibiotic-mediated cell death. (b) An antibiotic-resistant mutant produces indole by catabolizing tryptophan. Indole boosts the survival capacity of the population by inducing drug efflux pumps and oxidative stress detoxification pathways in the more vulnerable cells. (c) A subpopulation of dormant cells, persisters, is tolerant to antibiotics. Addition of specific metabolites, such as fructose, mannitol, or glucose, to the extracellular environment sensitizes persisters to aminoglycoside antibiotics via generation of proton motive force. (d) Some bacteria are capable of subsisting on antibiotics as a sole carbon source. They may allow a microbial community to evade treatments by reducing the local drug concentration, leading to formation of antibiotic-resistant mutants via mutagenic hydroxyl radicals, or by eliminating the antibiotic altogether.